Lani Estill is serious about wool. And not just in a knitting-people-sweaters kind of way. Estill and her husband John own thousands of sweeping acres in the northwest corner of California, where they graze cattle and Rambouillet sheep, a cousin of the Merino with exceptionally soft, elastic wool.

“Ninety percent of our income from the sheep herd comes from the lamb we sell,” says Estill. But the wool, “it’s where my passion is.”

Wool, an often-overlooked agricultural commodity, has also opened a number of unexpected doors for Bare Ranch, the land Estill and her family call home. In fact, their small yarn and wool business has allowed Lani and John to begin “carbon farming,” or considering how and where their land can pull more carbon from the atmosphere and put it into the soil in an effort to mitigate climate change. And in a rural part of the state where talk of climate change can cause many a raised eyebrow, such a shift is pretty remarkable.

Rambouillet sheep. (Photo credit: Paige Green)

Over the last two years, the Estills have started checking off items from a long list of potential changes recommended in a thorough carbon plan they created in 2016 with the help of the Fibershed project and Jeffrey Creque, founder of the Carbon Cycle Institute (CCI). The plan lists steps the ranchers can take to create carbon sinks on their property. And in the first two years, they’ve gotten started by making their own compost out of manure and woodchips and spreading it in several strategic places around the land.

They’ve also planted more vegetation in the areas of the ranch that border on streams and creeks to help them absorb carbon more efficiently, and this year they’ll be putting in a 4,000-foot row of trees that will act as a windbreak, as well as a number of new trees in the pastured area, applying a practice called silvopasture.

All these practices have allowed the Estills to market their wool as “Climate Beneficial,” which is a game-changer for them. They’ve also sold wool to The North Face, which used it to developed the Cali Wool Beanie—a product the company prominently touts as climate-friendly. The company, which has marketed several other regional products as part of their ongoing collaboration with Fibershed, also gave the Estills a one-time $10,000 grant in 2016 that the ranchers combined with some state and federal funding to help them start enacting parts of their carbon plan.

Like the Estills, the owners of dozens of farms, vineyards, and ranches in 26 counties around California have drawn up ambitious carbon plans that take into account the unique properties of each operation and lay out the best, most feasible ways to absorb CO2 over the long term. In arid ranching counties like Marin, that might mean re-thinking grazing practices, while in Napa Valley it could mean building soil in vineyards by tilling less and planting cover crops, and in San Diego County, it may mean protecting existing citrus and avocado orchards from encroaching development and working with farmers to plant more orchards.

It’s early days for the effort, but in a state that plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030—the most ambitious target in North America—these plans are laying out a solid plan to help farming and ranching become heavy hitters in the fight against climate change. They’re also helping create a model that is being watched closely by lawmakers in states like Colorado and Montana, where other carbon farming projects are coming together.

Agriculture accounts for around 8 percent of California’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but that number doesn’t quite reflect the impact of the gases themselves. Croplands in the state are the primary contributor of nitrous oxide, the most potent GHG, and account for 50 percent of the N2O that ends up in the atmosphere. While the bulk of the state’s methane emissions—25 times more damaging to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide—also originate on animal farms. On a global level, food production accounts for between 19 and 29 percent of climate-warming GHG emissions.

Lani Estill. (Photo credit: Paige Green)

It’s not surprising then, that some farmers are eager to be part of a solution. But as the rubber hits the road in California, the big question is how farmers will fund these changes. While solutions like the ones the Estills are tapping into, which combine consumer interest with public funding, seem promising, there’s still a long way to go before the efforts scale up in earnest around the state.

The momentum may be growing, however: The Marin Carbon Project, which pioneered carbon farming in California, recently had its day in the sun with a New York Times Magazine feature. And success stories like that of the Estills may soon bring more food producers on board.

A Beneficial Partnership

For Lani Estill, everything began to change in 2014, when she developed a small yarn brand. But she was only able to sell a small percentage of the wool directly to consumers, and most of it went to the wholesale market, where it sold for next to nothing. Some years, Estill says, they’d store it to see if they could get a better price the following year.

In 2014, Estill met Rebecca Burgess, a persuasive enthusiast of California wool with a vision to reinvigorate the supply chain for regional fiber, yarn, and cloth while building a market for those things simultaneously. Burgess, who had built a statewide network of fiber producers through her Fibershed network, was connected with the Marin Carbon Project and several other nonprofits campaigning hard to make carbon farming a reality.

When the idea came up to write a carbon plan, with funding from The North Face, Estill says it took some convincing. “Ranchers have been threatened constantly by the environmental community,” Estill told Capitol Public Radio in January. “So, we had to kind of open up our minds a little bit to accept what was being offered as a genuine offer.”

Burgess had also developed the “Backyard Project” with The North Face, which revolved around creating a shirt, and then several sweatshirts, using a transparent, mostly regional supply chain. The beanie made with climate beneficial wool was a natural next step.

“We make products so people can go explore and enjoy nature. And addressing climate is obviously an important issue,” says James Rogers, director of sustainability at The North Face. Based on their own internal lifecycle assessments, the company also determined that focusing on the types of materials it uses and how those materials are made offered the most effective way to address its environmental impact.

But Rogers says that the chance to make a positive impact was also appealing. “Frankly, a lot of companies are trying to do less bad, by reducing their environmental impact. And the thing that’s so exciting about climate beneficial wool is that through those ranching practices [the Estills] are actually taking carbon out of the atmosphere and sequestering it into the soil, while at the same time making that soil more healthy and retaining more water. So instead of just trying to be less bad, we’re actually doing more good.”

The Cali Wool Beanie was the top-selling beanie on The North Face’s website when it was released last fall, suggesting that some consumers are onboard with supporting carbon farming with their dollars.

The North Face’s promotion of the Cali Wool Beanie. (Photo courtesy The North Face)

But Fibershed’s Burgess adds that, although the climate benefits are front and center in the marketing, the carbon plans themselves are an ongoing process. “With the beanie, we’re working toward every pound of wool representing nine pounds of carbon sequestered. But we’re not there yet,” she says. “We actually need people [and companies] to buy more wool at a re-valued price, which that beanie provides. The more wool sells, the more carbon we can sequester at Bare Ranch. And that’s actually how regenerative systems work. It’s call and response between us and the ecosystem.”

Lani Estill, who has begun to sell more of her wool at non-commodity prices, agrees. She’s also created a community supported cloth project (a CSA for wool) as a way to invite home crafters and small brands to take part in that call and response.

Mounting Evidence

The idea of crafting farm-specific carbon plans grew out of the Marin Carbon Project, a collaborative research effort between landowners John Wick and Peggy Rathmann, scientists at the University of California, and several conservation groups. Launched in 2008, the project has spent the last decade looking at the role that applied compost and grazing management practices can play in helping soil absorb more carbon from the atmosphere on the state’s 54 million acres of rangeland.

Whendee Silver, a professor of ecosystem ecology at the University of California, Berkeley, managed a team of researchers who compared the CO2 and water retained in a series of plots of land—one where a thin layer of compost was applied, one that was plowed, one where both compost application and plowing took place, and a control plot.

In 2014, the team published the first round of evidence that showed that compost applications and other carbon farming techniques have the potential to help mitigate climate change by building biomass and transferring carbon from the atmosphere back into the soil.

The researchers found that a single application of a half-inch layer of compost on grazed rangelands can increase grass and other forage plant production by 40 to 70 percent, help soil hold up to 26,000 liters more water per hectare, and increase soil carbon sequestration by at least 1 ton per hectare per year for 30 years, without re-application. And because the dairy manure the project used to create the compost would have otherwise released methane to the atmosphere, the result was particularly promising for the climate.

Spreading compost at Bare Ranch. (Photo credit: Paige Green)

“We’ve discovered is that there’s a version of agriculture that actually could transform atmospheric carbon into carbohydrates [i.e., grass] and soil carbon,” says Wick, who has spent over a decade evangelizing the benefits of carbon farming on his own ranch and envisioning a state where such practices become the norm. “So for us the challenge is how do we communicate that? Now that we have this new understanding, how do we inspire people to put new importance on the same old things that we’ve always looked at—like sunshine, rain, and soil?”

For Wick and others, this shift in perspective feels especially urgent. He points to the latest International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) risk assessment, which makes it clear that “emission reductions will no longer stop this runaway destabilization of the climate. It says, ‘We must develop an ongoing strategy of removing carbon from the atmosphere that is sustainable.’ And that’s what we’ve done. Agriculture is the only system on earth large enough—directly under human influence right now—to actually transform enough carbon to actually cool the planet, not just stop how warm it gets, but actually reverse that trend.”

This year, Wick has returned his focus to his own land, while a handful of nonprofits such as the CCI and the California Climate and Ag Network, as well as county-level resource conservation districts (RCDs), are carrying on the change to scale up the statewide effort.

Since 2013, CCI has been working with RCDs all over the state to craft carbon plans that speak to the specifics of each farm’s geography, soil type, and lifecycle. “We’re not just spreading compost everywhere,” says CCI’s Torri Estrada. “We want to get on a farm and really understand the ecology, the farm production, and really push the envelope and give them a very comprehensive assessment.”

Nancy Scolari, the executive director of the Marin Resource Conservation District, says it has been interesting to see carbon farming go from a fairly abstract concept to an actual set of fundable practices in just a few years.

For many farmers, she says, the fact that they can’t actually see carbon in the air or the soil, made the Marin Carbon Project “hard to really appreciate at first.” But when Silver’s research was released, Scolari says it filled in some important gaps in the wider conservation world.

“The reason RCDs were created in the first place was all around soil, after the Dust Bowl. If you completely overuse your soils, you’ll feel it in the end. So to kind of reconnect with that past has been pretty interesting,” says Scolari. “All of the information around increasing soil organic matter and total carbon is like, ‘wow, this is the piece we’ve been missing for some time now.’ And it’s a piece that farmers really connect with.”

And while Estrada admits that the interest so far has mostly come from farmers who are already working outside the agriculture mainstream, in most counties the early adopters, who want to make—and execute on—a carbon plan for their farms still outnumber the local RCDs’ capacity there. Four northern California counties—Napa, Sonoma, Mendocino, and Marin—have all developed templates that can be adapted in other parts of the state with rangelands, vineyards, orchards, and forests.

In Marin, 10 farms had completed carbon plans as of the end of 2017, and five more are working on them this year. But the Scolari says she only has a few small pots of potential funding—from land trusts, the state’s coastal conservancy, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Resource Conservation Service—to offer farmers.

“The biggest barrier to scaling is the technical assistance of farmers,” says CCI’s Estrada. “It really requires planning assistance, implementation assistance, and then monitoring, which the RCDs and others do. But it’s really underfunded.”

For instance, planning to spread a layer of compost across every acre of your farm may sound relatively simple, but the cost of making it (or buying it), hauling it, and spreading it can add up quickly. And no farm has executed on every item in their carbon plan just yet. “We have producers doing one or two practices, which is really great. But the bottom line budget for [the whole plan] is hundreds of thousands of dollars,” says Estrada.

Piles of compost to be spread. (Photo credit: Paige Green)

In 2017, the state set aside $7.5 million for the Healthy Soils Program and a larger Healthy Soils Act as part of its cap and trade program. That was a good start, says Estrada, but adds that Marin County alone “could spend that twice over with a full build-out of its plan.” And there are no funds allocated for healthy soils in the state’s current fiscal year budget.

Larger structural investments are also helping paving the way. Fifty million dollars from the cap and trade pool have also been made available to large dairy farms that compost their waste, at which point it can be made available to farms and ranches. And the state’s recycling agency has also set aside $72 million for new compost facilities.

When farmers are able to raise the funds to enact their carbon plans, they’re likely to see a return on their investment over the long term. “If we can increase organic matter in soils, we thereby increased water-holding capacity,” points out Scolari. And in drought-prone California, that alone has enormous value.

As John Wick sees it, money can definitely help kick-start the process of sequestering carbon on farms, but so can time.

In areas of Wick’s ranch where the soil was once losing carbon, he says, he’s seeing a slow but powerful process unfold. “Where we put compost, which we imported at first, we reversed that trend and that system is making more biomass so I can make even more compost on-site. So now making my own compost as medicine and putting a single dose on my poor soils creates even more [compost]. And so I have this sweet spot of success that’s expanding outward.”

Calla Rose Ostrander, a consultant who works with Wick as well as the People, Food and Land Foundation, acknowledges that the funding so far has been relatively small, but considering the scope of the work to be done, she believes the inflection point isn’t far off.

“It’s going to require funding from multiple places before farmers can fully get to where they are implementing this at scale on the landscape,” she says. “However, all those funding doors are open now. Now it’s just a matter of growing the size and amount of funds that come through to the ground. The pathways are built, the relationships are there, the interest is there. The crucial moment—and this happens in any movement—is how you get from, ‘we’ve got the ideas, we’ve got the policies’ to ‘we’ve got to get the money on the ground.’”

“We’ve built a new pathway from scratch,” adds Wick. “And it didn’t matter at first how much flowed through it—we’re testing it now for leaks and gaps. And so the first flow is trickling through. That’s the moment; and it’s a very exciting moment.”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – 2018

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – 2018 Des Moines Register

Des Moines Register

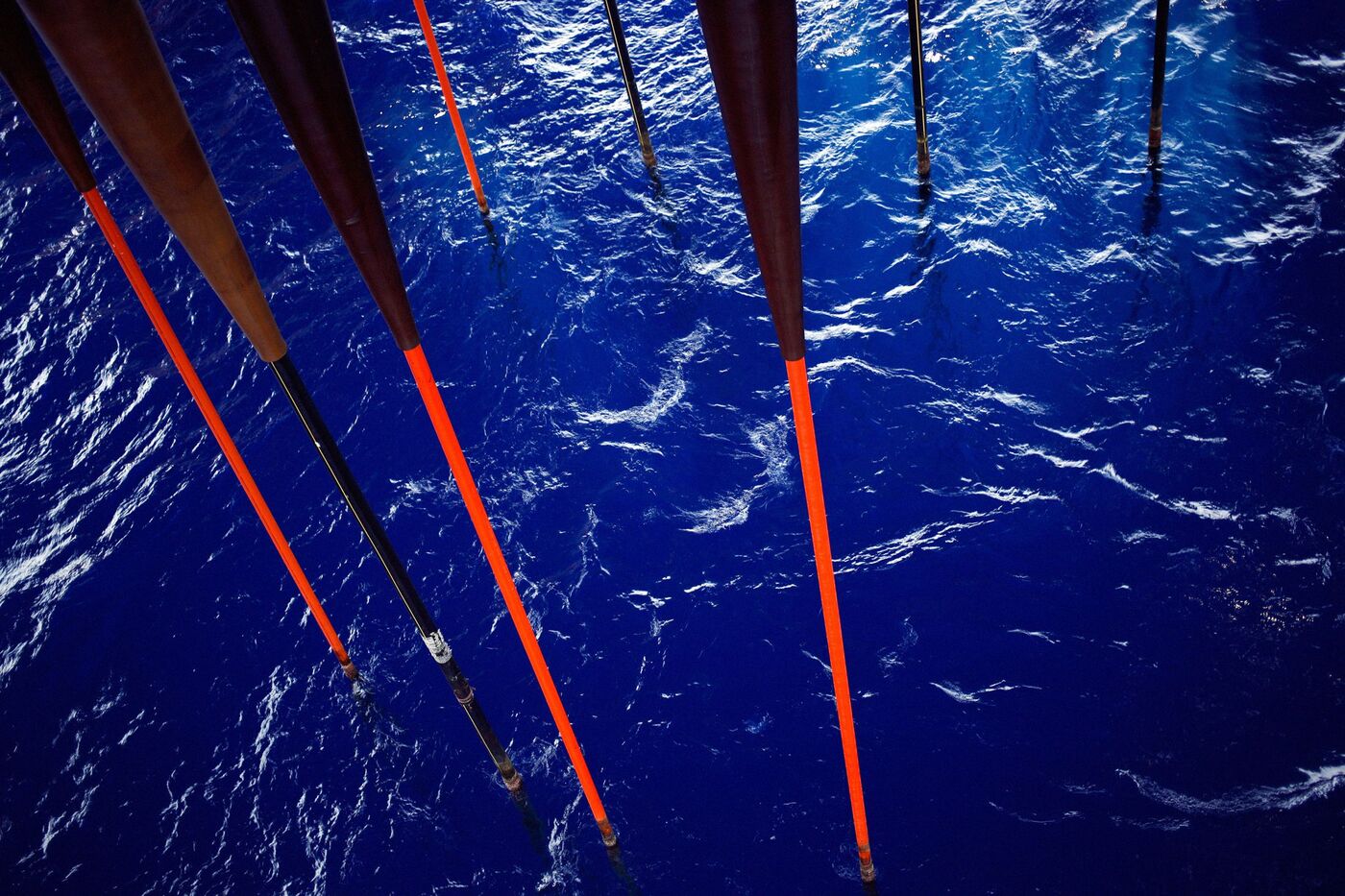

Pipes and mooring lines rise from the Gulf of Mexico beneath Chevron Corp.’s Jack/St. Malo deep-water oil platform about 200 miles off the coast of Louisiana on May 18, 2018. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg

Pipes and mooring lines rise from the Gulf of Mexico beneath Chevron Corp.’s Jack/St. Malo deep-water oil platform about 200 miles off the coast of Louisiana on May 18, 2018. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg Oil production equipment onboard Chevron’s Jack/St. Malo platform. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg

Oil production equipment onboard Chevron’s Jack/St. Malo platform. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg Platform supply vessel Kobe Chouest anchored alongside Jack/St. Malo. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg

Platform supply vessel Kobe Chouest anchored alongside Jack/St. Malo. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg Chevron workers examine hydrocarbon samples on Jack/St. Malo. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg

Chevron workers examine hydrocarbon samples on Jack/St. Malo. Photographer: Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg In this April 21, 2010, file photo, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig burns in the Gulf of Mexico following an explosion that killed 11 workers and caused the worst offshore oil spill in the nation’s history. President Donald Trump is throwing out a policy devised by his predecessor for protecting U.S. oceans and the Great Lakes, replacing it with a new approach that emphasizes use of the waters to promote economic growth. President Barack Obama issued his policy in 2010 after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Trump says it was too bureaucratic. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert, File)

In this April 21, 2010, file photo, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig burns in the Gulf of Mexico following an explosion that killed 11 workers and caused the worst offshore oil spill in the nation’s history. President Donald Trump is throwing out a policy devised by his predecessor for protecting U.S. oceans and the Great Lakes, replacing it with a new approach that emphasizes use of the waters to promote economic growth. President Barack Obama issued his policy in 2010 after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Trump says it was too bureaucratic. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert, File)