For more than four decades, Eric Holt-Giménez has been at the center of food movements across the globe that are seeking progressive social and economic change. From documenting the rise of the farmer-led sustainable agriculture movement in Central America to growing the food justice movement in North America as the executive director of Food First, Holt-Giménez’s work brings the perspectives of struggling communities to broader development and policy debates.

His new book, Can We Feed the World Without Destroying It?, is a three-part essay addressing the agronomy and ecology of farming, as well as the political economy of food. It covers the way resources, value, and power are distributed across the entire system—from farm to fork.

Feeding the world without destroying it will not simply require better food waste redistribution or climate-smart technologies, Holt-Giménez argues. Instead, it will also take social movements to create the political will for food system transformation. “How we produce and consume determines how our society is organized,” he writes. “But how we organize socially and politically can also determine how we produce and consume.”

Civil Eats recently spoke with Holt-Giménez about his new book, prevailing food system myths, and how a powerful food movement might catalyze society to demand the deep systemic reforms upon which he believes our collective future depends.

The book opens with the assertion that the global food system is subject to a whole new set of problems related to overproduction and over-consumption. Isn’t it counter-intuitive to produce more food than we could possibly consume?

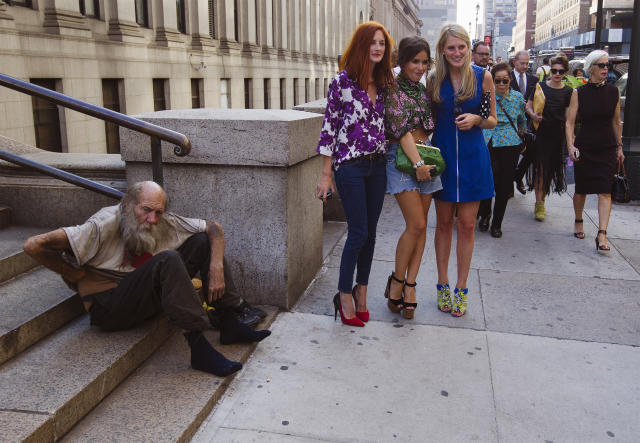

Overproduction is a chronic problem for capitalism—and for our food system. Though hunger and malnutrition are actually getting worse, we’ve been producing one-and-a-half times more than enough food to feed everyone on the planet for half a century. The glut of food keeps prices low for grain traders and processors of animal feed and junk food. Competition drives these companies to out-produce each other, each coming out with cheaper and cheaper processed food products. We end up with lousier food than the market can absorb and with a lot of grain-fed meat that hungry people can’t afford. Prices drop and margins shrink, but cheap food hasn’t ended hunger, and it comes at a tremendous social and environmental cost.

On one hand, 40 percent of food is wasted, so we are throwing away precious water, energy, and nutrients and producing a lot of unnecessary methane. Driving the land to produce more than its soils and aquifers can naturally sustain degrades and erodes not just farms, but the surrounding environment.

Our food system is a major source of greenhouse gases, and the over-fertilization of crops results in contaminated aquifers and massive “dead zones” in our lakes and oceans. Our bodies have become toxic dumps for the chemicals and antibiotics used in industrial food production, and we have at least as many people suffering malnutrition and diet-related disease as there are from hunger.

Overproduction results in monopolization up and down the food chain, giving agri-food corporations tremendous economic and political power to continue doing business as usual. These unregulated firms pay for none of the “externalities” they produce—we do.

Yet there are repeated calls for the need to double food production by 2050 to feed the world. Why does the scarcity myth prevail?

Scarcity serves several important functions in a capitalist economy, especially with food. Because capital can’t expand when markets are saturated, scarcity must be constantly created, both materially and ideologically. Corporations perpetuate the myth of scarcity because if the real reason for hunger was revealed, then society would begin to question the efficiency and the moral foundation of the capitalist food system.

The thing about the myth of scarcity is that it both manipulates and obscures the difference between need and demand. Nearly a third of the world’s human population needs more healthy food to meet their daily nutritional requirements than they can afford to buy.

The real market demand for food is for cheap meat to meet the appetites of the expanding middle class, so much of the investment in “food” is really an investment in the cultivation of feed for grain-fed livestock and poultry. This doesn’t feed the poor at all, but under the guise of “feeding the world,” it expands the markets of the seed, chemical, grain, and livestock industries.

Corporations invite us to believe that if we just produced more cheap food, poor people would be able to afford it, and we’d end hunger. But even the cheapening of food hasn’t lowered the ratio of hungry people in the world, because most of the world’s hungry are poor farmers who actually produce over half the world’s food on less than a quarter of the planet’s agricultural land. Essentially, poor people feed the poor.

Why do you feel that those trying to change the food system need to understand capitalism?

If we want to change it, we need to understand how it works. This seems straightforward, but because capitalism is so ubiquitous, it is invisible to many people in the food movement. On the other hand, those who do recognize it often feel as if it is so powerful the only thing we can do is accept it and work for minor reforms and safety nets to mitigate its damage to people and the environment. There is talk about a “food revolution” that has somehow taken place without affecting the power of capitalist food monopolies.

Because our global food systems respond to the logic of capital, problems like hunger, malnutrition, and global warming are viewed as opportunities for profit. Therefore, technological innovations that can be bought and sold on the market as commodities take precedence over other proven redistributive approaches such as land reform and agroecological diversification.

It’s fashionable these days to talk about “disrupting” the food system with clever apps, but in reality, technical solutions are carefully selected to fit into the existing system in ways that enhance rather than fundamentally challenge the power of agribusiness monopolies or the industrial model of production. Since the capitalist model is at the heart of the problem, this leads to some remarkably contradictory approaches.

For example, virtually none of the proposals to deal with food waste (composting, feeding pigs, selling “ugly fruit,” etc.) address the cause of food waste: capitalist overproduction. Farmers are competing with each other—ramping up production—to sell to the new “waste market”. Simple supply management quotas coupled with fair price floors for farmers could eliminate overproduction, but these well-known measures are ignored in favor of inventing new commodities. The food waste industry is in its infancy right now, and there is a lot of excitement about how this can help poor communities. But these start-ups will be eventually taken over by the retail monopolies. Then prices to farmers will drop, and prices to consumers will rise.

Another example is “climate-smart” agriculture. Giant soy, maize, and wheat plantations in the U.S. and Latin America are celebrated for using “precision agriculture” and “big data” to make efficient use of fertilizers and pesticides. But these plantations are displacing diversified small farms, grasslands, and forests at an astonishing rate in order to supply feed to confined animal feedlot operations (CAFOs) in China and the U.S. As researcher Marcus Taylor of Queens University in Canada quipped, climate-smart agriculture is really “climate-stupid consumption.”

What specific policies should members of the food movement come together to change?

Now is the time to push for transformative reforms that address overproduction, poverty, exploitation, and climate change by rolling back monopoly power and creating favorable conditions for a more localized, resilient, and equitable food systems worldwide.

We need strong antitrust laws, especially for the retail, grain, and chemical monopolies. The financial sector needs to be regulated to stop speculation with our food. Agricultural land should be de-commodified and made accessible to family farmers and to young farmers who want to prioritize local markets and regenerate local watersheds. Issues of equity and reparations should be addressed through redistributive policies. These farmers need to be supported by fair, parity prices conditioned on sustainable, regenerative practices that build resiliency and guarantee fair labor practices for farm and food workers.

We need supply management programs that stop overproduction, and we need to level the playing field between family farms and monopolistic corporations by using a “polluter pays” principle and demanding fair, living wages for all workers. Grain reserves should be re-established to help keep prices stable and hedge against shortages. Local, cooperative banks and credit associations need to be supported and guaranteed by the federal government to make local loans in agriculture, housing, and local businesses.

We need to ensure good health, education, and welfare policies in the countryside through investments in the “social wage”– i.e., public investments in the health, education, and welfare of rural and peri-urban communities. The countryside needs to be a good place to live, and farming should be desirable work. This would go a long way to a real food revolution.

Do the U.S. food and farm justice movements have an opportunity to drive some of these transformative reforms by getting behind something like the Green New Deal?

Much like the era of the Great Depression, today, our farm, food, and climate justice movements are calling for sweeping reforms for a Just Transition to shift from an extractive economy to a resilient, regenerative, and equitable economy. While these alliances are coming together, they have yet to articulate a clear agrarian vision for a just climate transition. I’d say that is high on the list for a powerful convergence.

On the crest of the recent “blue wave” in the U.S. Congress, new leadership proposed a Green New Deal to address the climate crisis. But the initiative faces political obstacles in Congress, and it is not clear just how a Green New Deal will ensure the participation and equity demanded by social justice movements.

As expected, the corporate wing of the Democratic Party is resisting the Green New Deal. Nevertheless, I think we need to take advantage of the present political moment. If farmer, farmworker, climate, and racial justice leaders come together to envision a New Deal for a Just Transition, whatever happens, we can advance the broad-based, multi-racial, working-class alliance we need to reverse global warming and transform the food system.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.