Could the electric car save our climate?

What If All Cars Went Electric

Could the electric car save our climate?

Posted by What.If on Thursday, May 31, 2018

Read About The Tarbaby Story under the Category: About the Tarbaby Blog

Could the electric car save our climate?

What If All Cars Went Electric

Could the electric car save our climate?

Posted by What.If on Thursday, May 31, 2018

By Michael Hawthorne, Chicago Tribune May 30, 2018

Chicago: The first sign of trouble on Illinois’ only national scenic river is when thick stands of sycamore, red bud and oak suddenly give way to a barren, rocky bank stained metallic hues of orange and purple.

Pools of rust-colored water stagnate along the edge of the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River as the otherwise clear, fast-moving stream meanders past the source of the unnatural phenomena: three unlined pits of coal ash dug into the floodplain by owners of a now-defunct power plant that generated enough toxic waste during the past half century to fill the Empire State Building nearly 2 1/2 times.

Internal reports prepared by Texas-based Dynegy Inc., the last owner of the former Vermilion Power Station, have shown the multicolored muck seeping into the river is concentrated with arsenic, chromium, lead, manganese and other heavy metals found in coal ash. State environmental regulators confirmed the findings more than a decade ago, yet pollution continues to ooze into the Middle Fork.

With the administrations of President Donald Trump and Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner rolling back enforcement of national and state environmental laws, advocates are urging a federal court to step in and order Dynegy to take more aggressive action. Environmental groups fear that steady erosion of the riverbank could trigger a catastrophic spill, similar to disasters at coal plants in Tennessee and North Carolina where ash impoundments ruptured and caused millions of dollars in damage.

“Dynegy left a toxic mess on the banks of one of Illinois’ most beautiful rivers and has done nothing to stop the dangerous, illegal pollution from fouling waters enjoyed by countless families who kayak, tube, canoe and even swim in the river,” said Jenny Cassel, an attorney with Earthjustice, one of the nonprofit groups behind a lawsuit filed Wednesday that accuses Dynegy of violating the federal Clean Water Act.

The Middle Fork winds through east central Illinois amid corn and soybean fields and clusters of wind turbines rising above moraines that interrupt the flat farmland. About 17 miles of the river in Vermilion County are protected under the federal National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, including the stretch that flows past the shuttered coal plant about a mile downstream from a popular canoe and kayak launch. The river and surrounding woods are home to dozens of endangered and threatened species, including bald eagles, bluebreast darters and several species of freshwater mussels.

Last month another nonprofit group, American Rivers, cited the ongoing threats to recreation and aquatic life when it named the Middle Fork one of the nation’s most endangered waterways.

Dynegy consultants have estimated it could cost up to $192 million to transfer 3.3 million cubic feet of coal ash from the Vermilion plant to a licensed landfill. The company once suggested it could cap the waste pits to prevent rain and snowmelt from washing coal ash into the water, but another Dynegy report estimated the normal flow of the Middle Fork is eroding the river banks by up to 3 feet a year, making it more likely the toxic slurry will be exposed if left in place.

As Dynegy struggled to keep the rest of its Illinois coal plants operating in the downstate power market, it was absorbed in April by another Texas-based company, Vistra Energy, which reported earnings of $1.4 billion in 2017. Neither company responded to requests for comment about the lawsuit.

The Vermilion plant is one of two dozen sites in Illinois where energy companies have dumped coal ash for years. Most waste is stored close to rivers and lakes used for cooling water, and the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency considers 10 of the other sites to pose serious threats to the drinking water supplies of nearby communities.

Illinois Power, which built the Vermilion plant in 1955 and sold it to Dynegy in 2000, tried to prevent its ash pits from leaking during the 1980s by stacking rock-filled wire cages along the river. But torrents of high water during and after storms have washed away many of the protective formations, exposing steady trickles of pollution through fractured sandstone and shale.

During a trip down the river in early May, three advocates who frequently paddle the Middle Fork said the problems appeared significantly worse than what they saw last fall. Andrew Rehn, water resources engineer for the Prairie Rivers Network, the chief plaintiff in the federal lawsuit against Dynegy, said he has seen waste seeping from the riverbank every time he has been on the river during the past eight years.

“Over the years the utilities have used the floodplain as essentially a dumping ground,” said Lan Richart, a former Illinois Natural History Survey ecologist who along with his wife, Pam, formed another group pushing to protect the Middle Fork. “Now it’s been shown to be polluting both the groundwater and the river.”

Smallies

Smallies

Because the Vermilion plant closed years ago, the ash pits are exempt from federal regulations enacted by the Obama administration in 2015 in response to the Tennessee and North Carolina spills. Opposition from Dynegy and other energy companies led the Trump administration last year to reconsider the safeguards; a separate proposal in Illinois that would impose stricter regulations on coal ash pits also has been sidetracked.

At the same time, enforcement actions against the owners of coal ash pits have stalled. The Illinois EPA cited Dynegy in 2012 with violations of state water quality standards but has yet to resolve the case. Federal environmental regulators have not responded to requests for them to intervene.

The Chicago Tribune reported in February that since Rauner took office in 2015, penalties sought from Illinois polluters have dropped to $6.1 million – about two-thirds less than the inflation-adjusted amount demanded during the first three years under the Republican chief executive’s two predecessors, Democrats Pat Quinn and Rod Blagojevich.

At the federal level, Trump’s EPA administrator, Scott Pruitt, has slowed enforcement and restricted the agency’s staff from filing new cases. Several recently announced legal settlements with polluters were prompted by citizen lawsuits similar to the one filed Wednesday against Dynegy.

Over 3.3 million cubic yards of toxic coal ash have been dumped in the floodplain of this scenic river. Coal ash, a byproduct of burning coal, contains some of the most toxic substances known to humankind.

This pollution is associated with the operation of the coal-fired power plant on the west bank of the river. The plant, now owned by Dynegy-Midwest Generation, is closed. But the natural forces of the river threaten the river bank and abutting impoundments, raising concerns over a possible breach. Two of the three ponds are leaking, and the third sits over mine voids. Learn more about the threat to the river.

The Middle Fork of the Vermilion River is Illinois’ only National Scenic River.

The Middle Fork of the Vermilion River is Illinois’ only National Scenic River.

It runs freely through a variety of habitats, including forest and steep bluffs.

It runs freely through a variety of habitats, including forest and steep bluffs.

The Middle Fork supports a variety of aquatic life, including over 57 species of fish.

The Middle Fork supports a variety of aquatic life, including over 57 species of fish.

The river is a great spot for sport fishing. Photo courtesy of IDNR.

The river is a great spot for sport fishing. Photo courtesy of IDNR.

Over 10,000 people canoe, kayak or tube the Middle Fork each year.

Over 10,000 people canoe, kayak or tube the Middle Fork each year.

Hiking trails offer great views of the Middle Fork.

Hiking trails offer great views of the Middle Fork.

All three pits are in the floodplain and subject to natural forces of the river.

All three pits are in the floodplain and subject to natural forces of the river.

Riverbank armoring installed in the 1980’s to protect the banks is failing, and toxic metals are leaching into the river.

Riverbank armoring installed in the 1980’s to protect the banks is failing, and toxic metals are leaching into the river.

Dyengy wants to cap the pits, stabilize the riverbanks, and move on.

Dyengy wants to cap the pits, stabilize the riverbanks, and move on.

The only way to protect the river long-term is to move the ash out of the floodplain, away from the river.

The only way to protect the river long-term is to move the ash out of the floodplain, away from the river.

Act to protect the Middle Fork today! Click ACT NOW in the menu bar and scroll to send letters to Illinois’ Governor and EPA Director; state officials; and local officials.

The Resource – Illinois’ Only National Scenic River

The Middle Fork of the Vermilion River is Illinois’ first designated State Scenic River. It also is the state’s only designated National Scenic River. These designations recognize the Middle Fork’s outstanding scenic, recreational, ecological and historical characteristics.

Ecological and Scenic Significance

The Middle Fork River has eroded through deep glacial deposits, exposing steep valley slopes, and high bluffs and hillsides with natural springs. Most of the area along the river is forested, but there are also several prairie sites. Three of these support plants and animals so rare that they are protected as State Nature Preserves.

The Middle Fork river valley supports a great diversity of plants and animals. They include 57 types of fish; 45 different species of mammals; and 190 kinds of birds. Twenty-four species are officially identified as State threatened or endangered.

And there are other qualities of the Middle Fork river valley that make it unique to Illinois. These include unusual geologic formations; several historic sites, and over 8,400 acres of public parks.

Illinois Law (Public Act 84-1257) and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act give permanent protection to a 17-mile segment along both sides of the Middle Fork. Conservation easements are held by the state on all land it does not own. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources manages this protected river valley. The state nature preserves and state threatened or endangered species in the valley are protected by other state laws and programs.

Recreation and Historic Importance

The river system also provides the benefits of a strong recreation economy to Vermilion County. Kickapoo State Park, Kennekuk County Park, and the Middle Fork State Fish and Wildlife Area stand as key destinations for local residents and visitors, enjoyed for canoeing, kayaking and tubing; wildlife viewing; photography; hunting; angling; hiking; and horseback riding. Kickapoo Adventures, located in Kickapoo State Park, puts over 10,000 people on the Middle Fork River in canoes, kayaks and tubes each year.

A Source of Food

In addition to the river’s scenic, historic, and recreation importance, this stretch of the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River provides a reliable source of food for some area residents. The loss of the manufacturing base in the nearby city of Danville has left many unemployed and living in a subsistence economy.

You Can Help Protect the Middle Fork!

Dynegy is seeking approval of their closure plan for these three coal ash pits from the Illinois EPA. Their plan is to cap them and leave them in the floodplain.

One easy way to take action now is to send an electronic letter to State Senator Scott Bennett and State Representative Chad Hays; Danville’s Mayor Scott Eisenhauer and County Board Chair Michael Marron; and Governor Rauner and the Alec Messina, Director of the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA). Ask them to require Dynegy to move its coal ash from the floodplain to a properly-designed facility on its property, away from the river. Personalizing your letter will have the most impact.

Other states are requiring utility companies to relocate their ash, so why aren’t we?

Lorraine Chow May 30, 2018

The world’s most powerful wind turbines are now in place in Aberdeen Bay. Vattenfall

The world’s most powerful wind turbines are now in place in Aberdeen Bay. Vattenfall

The world’s most powerful wind turbines have been successfully installed at the European Offshore Wind Deployment Centre (EOWDC) off Aberdeen Bay in Scotland’s North Sea.

The final turbine was installed on Saturday just nine weeks after the first foundation for the 11-turbine offshore wind farm was deployed, according to the developers Vattenfall.

Incidentally, the project was at the center of a contentious legal battle waged—and lost—by Donald Trump, before he became U.S. president. Trump felt the “ugly” wind turbines would ruin the view of his Menie golf resort.

“I am not thrilled,” Trump said in 2006, as quoted by BBC News. “I want to see the ocean, I do not want to see windmills.”

But in 2015, the UK Supreme Court unanimously rejected Trump’s years-long appeal against the wind farm, which now stands 1.2 miles from his luxury golf course.

The EOWDC, Scotland’s largest offshore wind test and demonstration facility, is scheduled to generate power in the summer. At full capacity, the 93.2-megawatt plant will produce the equivalent of more than 70 percent of Aberdeen’s domestic electricity demand and displace 134,128 tonnes of CO2 annually, Vattenfall estimates.

The wind farm features nine 8.4-megawatt turbines and two 8.8-megawatt turbines. The larger turbine, with a tip-height of 627 feet and a blade length of 262 feet, can power the average UK home for an entire day with a single rotation, the engineers tout.

“This is a magnificent offshore engineering feat for a project that involves industry-first technology and innovative approaches to the design and construction. Throughout construction, the project team and our contractors have encountered, tackled and resolved a number of challenges,” said Adam Ezzamel, EOWDC project director at Vattenfall, in a statement. “The erection of the final turbine is a significant milestone, and with the completion of array cable installation, we now move on to the final commissioning phase of the wind farm prior to first power later this summer.”

Vattenfall also believes it achieved the world’s fastest installation of a giant suction bucket jacket foundation.

“One of our 1,800-tonne suction bucket jacket foundation was installed in what we believe is a world record of two hours and 40 minutes from the time the installation vessel entered the offshore site until deployment was complete,” Ezzamel said. “What makes this even more significant is that the EOWDC is the first offshore wind project to deploy this kind of foundation at commercial scale while it’s also the first to pair them with the world’s most powerful turbines.”

Watch here for time-lapse footage of the installation:

RELATED ARTICLES AROUND THE WEB

Scotland’s Record-Breaking Wind Output Enough to Power 5 Million

Trump sent wind farm complaints to Scottish first minister: report

On Navajo land in Arizona, a coal plant and coal mine that have devastated the environment are being replaced by solar–with both enormous benefits and local drawbacks that can serve as a lesson for how the rest of the country will need to manage the transition to renewables.

By Adele Peters May 30, 2018

Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority

Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority

In the desert near Arizona’s border with Utah on the Navajo Nation, a massive solar array built in 2017 now provides power for around 18,000 Navajo homes. Nearby, construction will begin later this year on a second solar plant. And on another corner of Navajo land, the largest coal plant west of the Mississippi River is preparing to close 25 years ahead of schedule, despite some last-minute attempts to save it.

“Those two [solar] plants really are the beginning of an economic transition,” says Amanda Ormond, managing director of the Western Grid Group, an organization that promotes clean energy.

The coal plant, called the Navajo Generating Station, was built in the 1970s to provide power to growing populations in Southern California, Arizona, and Nevada. A nearby coal mine supplies the power plant with coal. As recently as 2014, the coal plant wasn’t expected to close until 2044–a date negotiated with the EPA to reduce air pollution. But reduced demand for coal, driven both by economics and climate action, means that the plant is scheduled to close in 2019 instead. The coal mine, run by Peabody Energy, will be forced to follow.

In 2016, Los Angeles, which owned a 21% share in the plant, completed a sale of its share to reduce city emissions. In 2017, the remaining owners announced that they would close the plant because coal power is no longer economically competitive. The plant’s largest customer, the Central Arizona Project, calculated that if it had purchased electricity from other sources in 2016, it could have saved $38.5 million.

Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority

Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority

Though customers no longer want the coal, there’s some resistance to the early closure. Both the coal plant and the coal mine provide tribal revenue and jobs in an area where nearly half the population is unemployed. The coal plant owners are helping employees find new work, but some mine workers–along with Peabody Energy, which runs the coal mine on land that straddles the Navajo and Hopi reservations–are fighting to keep the plant open. The electric plant is the sole customer of the coal mine, so if the plant goes, so will the mine.

A lawsuit, filed by Peabody, coal miners, and the Hopi tribe, argues that the Central Arizona Project has to keep buying the coal under the terms of its contract as long as the plant is open–and efforts are being made to find a new buyer. (So far, the owners have shared information with some potential buyers, but haven’t received any offers.) An Arizona congressman drafted a bill that would exempt a new owner of the coal plant from some environmental regulations and force the Central Arizona Project to keep buying the power.

But while some living in the area want to try to keep coal going, others say that it makes more sense to shift to renewables. “There’s all this propaganda that’s been created saying that the Navajo are going to be devastated, the Hopis are going to be devastated,” says Percy Deal, a local activist. “We’ve already been devastated.” Deal, who is 68 years old, says that he has witnessed the destructive impact of the coal industry over its nearly 50-year history in the area.

The coal industry uses massive amounts of water in an area that has little of the resource. For decades–including a current long drought–the plant and mine have taken water from an aquifer that both the tribe and local wildlife rely on. (Another mine, which closed in 2005, used even more water as it pumped coal through pipes to Nevada.)

“Peabody can afford to drill deep wells . . . the people can’t afford to drill deep wells,” says Nicole Horseherder, another Navajo activist. “The people have been using springs and seeps for centuries, and the amount of water mining that Peabody does has an impact on the springs and seeps, and people’s ability to obtain and access water.”

Natural springs have run dry. Windmills that used to pull up water from an aquifer no longer can. Thousands of Navajo families still don’t have running water. Plants that were used in traditional food, medicine, and to dye rugs no longer grow in the area.

“Many of our wildlife–for example, deer, elk, antelope–these are all gone,” Deal says. “They have moved on to other areas simply because they cannot find these plants anymore. We also noticed that the bald eagles and other hawks have moved on. These are sacred animals to the Navajo and Hopi people.” Other animals, including a herd of wild horses discovered dead in early May, have died of dehydration.

The coal plant emits more greenhouse gas pollution than roughly 3 million cars, contributing to the changing climate that is, in turn, leading to both drought and heat waves in the area. The plant also emits thousands of tons of nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide pollution a year, which can cause lung disease, heart attacks, and strokes. Other pollutants from the plant, like lead, mercury, and manganese, can cause brain damage.

“When the plant and the mine close, for us that are living in the area, it’s a new beginning toward a healthier life,” Deal says.

Renewable energy can also bring new economic opportunity. When the coal plant owners decided to close in 2019, part of the agreement included turning over a 500-megawatt transmission line to Navajo tribal government. “We can see that having the transmission line is the greatest economic opportunity that the Navajo nation has ever had,” Deal says.

“It’s a great asset for the tribe, because they could either sell the rights of that transmission and make money, or they could develop their own projects . . . and use the transmission right to be able to sell pretty much to anybody in the western United States,” says Ormond. In addition to abundant sunshine, the Navajo reservation also has the best wind resources in Arizona, at Gray Mountain.

The first Kayenta solar farm, which started operating in April 2017, has 120,000 panels mounted on trackers that follow the sun to generate as much power as possible. It generates 27.3 megawatts of electricity, which is sold to Salt River Project, which also runs the coal plant. The power is sent across the reservation and to cities in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and California. At the height of construction, the project employed 284 people, the majority of whom were Navajo. The solar installation skills that workers gained can be used in the next solar plant, which will generate another 27.3 megawatts of power.

Nicole Horseherder argues that if the Navajo nation wants to stay in the energy business, it should invest in expanding its own solar power. “We’re saying, this way you’re producing it, you own it, you maintain it, you operate it, and you have so much more control over the revenue stream and the type of jobs that can be created,” Horseherder says.

If someone buys the coal plant to keep it running, Ormond says, that doesn’t guarantee that it will preserve good jobs. “The idea that someone can come in and run it more economically–the only way you’re going to do that is by cutting costs, and you’re not going to cut costs of operating the plant, you’re going to cut the cost of workers and pensions and coal,” she says. “So I just don’t see it happening.”

If more solar power provides electricity locally–in an area where many residents still don’t have power themselves–it could also make it possible to support different types of work. “You’ve got the basics for building a different economic future, because you’ve got lots of land, you’ve got sunshine, you’ve got power, you’ve got water,” says Ormond. And this could be possible, she says, without inflicting further harm. “Once you put up a solar plant, it just sits there and produces money and energy. It doesn’t use water, and it doesn’t degrade the landscape.”

About the author: Adele Peters is a staff writer at Fast Company who focuses on solutions to some of the world’s largest problems, from climate change to homelessness. Previously, she worked with GOOD, BioLite, and the Sustainable Products and Solutions program at UC Berkeley.

You Might Also Like:

The Energy Department Is Making Up Reasons Why You Need To Pay More For Dirty Energy

Can Puerto Rico Be The Model For A Renewables-Powered Energy System?

During Puerto Rico’s Blackout, Solar Microgrids Kept The Lights On

By Steve Benen May 29, 2018

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump talks with press on Sept. 5, 2016, aboard his campaign plane, while flying over Ohio, as Vice presidential candidate Gov. Mike Pence looks on. Photo by Evan Vucci/AP

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump talks with press on Sept. 5, 2016, aboard his campaign plane, while flying over Ohio, as Vice presidential candidate Gov. Mike Pence looks on. Photo by Evan Vucci/AP

Donald Trump asked over the holiday weekend why neither the FBI nor the Justice Department contacted him during the 2016 campaign to alert him to the “Russia problem.” Those who haven’t paid close attention to this story might’ve seen the president’s point as having merit.

Indeed, former White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer declared, “This is a good question that deserves an answer.”

The trouble is, the question was already answered months ago. NBC News had this report in December 2017:

In the weeks after he became the Republican nominee on July 19, 2016, Donald Trump was warned that foreign adversaries, including Russia, would probably try to spy on and infiltrate his campaign, according to multiple government officials familiar with the matter.

The warning came in the form of a high-level counterintelligence briefing by senior FBI officials, the officials said. A similar briefing was given to Hillary Clinton, they added. They said the briefings, which are commonly provided to presidential nominees, were designed to educate the candidates and their top aides about potential threats from foreign spies.

The candidates were urged to alert the FBI about any suspicious overtures to their campaigns, the officials said.

There are a couple of angles to this to keep in mind. The first is that Trump’s latest complaint – federal law enforcement should’ve given him a heads-up about the “Russia problem” during Russia’s attack on our political system – is difficult to take seriously given the counterintelligence briefing he received in 2016.

But for the president to remind us of this is especially unwise since because Trump did more than just ignore the warning – the Republican and his team also failed to volunteer information that would’ve mattered to the FBI at the time.

THE RACHEL MADDOW SHOW, 12/18/17, 9:08 PM ET

Republican attack on Mueller Trump investigation falls apart

Republican attack on Mueller Trump investigation falls apartAs regular readers may recall, Rachel explained on the show that we’ve kept track of the large roster of Russians connected to Putin’s government who were in contact with the Trump campaign or the Trump transition before the president’s inauguration. It’s not a short list.

And yet, neither Trump nor anyone on his campaign thought to mention any of this to federal law enforcement, even after the FBI warned Trump about Russians possibly trying to infiltrate his political operation.

In fact, by the time Trump received his first classified intelligence briefing, which came a month after the FBI warning, more than a half dozen Trump campaign staffers, including members of his own family, had already taken high-level meetings with Russians and people who were sent as emissaries from the Russian government.

They just didn’t think to tell intelligence officials about any of this. The FBI effectively said, “Let us know about suspicious overtures to your campaigns,” and Trump World, after hearing from a whole lot of Russians who wanted to partner with the Republican campaign, didn’t say anything.

It’s possible, of course, that the campaign’s communications with the Russians were benign. But if so, why not let U.S. officials know about the contacts, especially after the FBI specifically urged Trump and his team to report foreign overtures?

For that matter, what made Trump think it was a good idea to bring all of this up now?

By John Crudele May 28, 2018

Donald Trump, AP

Donald Trump, AP

That’s the opinion of a widely circulated Goldman Sachs report last week. That was also my opinion before, during and after Washington’s journey into the great unknown of tax reform.

That’s also why I proposed a solution for fixing and strengthening the economy that wouldn’t have gotten the US into the precarious position of adding an enormous amount of debt on top of our pre-existing mountain.

The US already owes more than $21 trillion. Some of that money is owed to American citizens who bought government securities. But a huge chunk is owed to foreigners, including China, OPEC and Japan.

So, for starters, there was a national security issue involved in adding more debt to the current load. When President Trump sits down to negotiate with Chinese President Xi Jinping about trade, North Korea or anything else, America is talking to the leader of a creditor nation — a massive one — who can have influence over the US economy.

That’s one issue.

The one that worries Goldman, as it does me, is how much America’s debt will grow because of the tax cuts. Then there’s the uncertainty of just how much they will benefit the US economy.

The US budget deficit was $600 billion during the first six months of the current fiscal year, which ends in September. The tax cuts, which began in January, added to that number.

That means, if the situation holds, the US will tote up a fiscal year deficit of more than $1 trillion.

Goldman chief economist Jan Hatzius, in his report, says Trump’s $1.4 trillion tax cut could contribute to an annual deficit spike of more than $2 trillion by 2028. “The US fiscal outlook is not good,” Hatzius says.

Damn right, it isn’t.

The situation will get even worse when — not if — interest rates rise and Washington has to pay more to get people to buy its securities. Rates are already up. But if bonds become unattractive to investors, rates will climb higher, making for a disaster scenario for the deficit.

What have I proposed — numerous times in this space?

Instead of embarking on the great unknown of the tax reform, Washington should allow Americans to dip into the huge stash of restricted money they have tied up in retirement accounts.

I haven’t proposed anything specific. That would have been for Washington to work out.

But I have suggested that Washington allow people to withdraw some of their retirement money, at a reduced tax rate, to invest in real estate. This plan does not increase the deficit but rather boosts tax revenue because people will have to pay some level of tax on their withdrawals.

As it turns out, the real estate market is the one part of the economy where prices are booming. So that part of my idea probably wouldn’t have been beneficial right now.

But the larger idea — allowing Americans to stimulate the economy using their retirement money — is valid. All that has to be done is to decide where this retirement money is allowed to flow and how much of it to release.

It’s too late for now, though. The tax cuts have already been passed and the results aren’t promising. Not only is the US total debt becoming even more dangerous, but there’s been little boost to the national economy, which this year is growing, so far, at only around 2 percent.

And, mainly because of the deficit, the financial markets are causing interest rates to rise and the Federal Reserve has had to be more aggressive in raising borrowing costs. As I’ve predicted, those higher rates are causing the US deficit to rise, sparking the proverbial vicious cycle of economic problems.

Soon you will hear other fiscal conservatives — on both sides of the aisle — expressing worry over the effects of tax cuts. Maybe, just maybe, this idea will get its chance to right the economic ship of state.

Goldman Sachs: Trump’s tax cuts could cause recession

The big tax cuts haven’t goosed consumer spending

America’s debt is set to soar — and it just got far worse

Trump tax cuts expected to raise federal deficit to $804B this year

Why gas prices are so high — and what Americans may have to risk to make them lower

By Chris Winters, orig. pub. by Yes Magazine May 25, 2018

For Julia Rosenblatt, the solution to affordable housing was to move in with friends and family—more than 10 people under one roof.

For Julia Rosenblatt, the solution to affordable housing was to move in with friends and family—more than 10 people under one roof.

Rosenblatt, a co-founder of the HartBeat Ensemble theater group in Hartford, Connecticut, had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances in local activist communities. The year was 2003, the United States had launched a war in Iraq, and the post-9/11 environment was making her think differently about what kind of life she was going to have for herself and her family. An initial group of about 20 people liked the idea of creating an intentional community: living together with a shared set of goals and values to have a life that would be more meaningful, less harmful to other communities and the environment—and more affordable.

In 2008, six people moved into one house. The big move came in 2014, when those six were joined by five more to buy a 5,800-square-foot 1921 house on Tony Scarborough Street in the city’s West End. The nine-bedroom house had been sitting empty for four years.

Rosenblatt, her husband, Joshua Blanchfield, and their children, Tessa and Elijah Rosenfield (a merging of their parents’ last names), now live with Dave and Laura Rozza and their son, Milo, plus another married couple, Maureen Welch and Simon DeSantis, and Hannah Simms. The other original group member left the home when he got married.

Everyone contributed to the down payment. DeSantis and Laura Rozza had the best credit, so the mortgage for the $453,000 purchase price was taken out in their names, while a separate legal agreement stipulates that everyone is a co-owner of the house.

“We couldn’t maintain ourselves as a four-person household,” Rosenblatt says. “There was no way we could have bought this house at all with any less than eight adults pitching in.”

There were additional considerations, too.

“It was the idea of sort of creating a new world we want to live in,” says Laura Rozza, a grant writer for a nonprofit serving people with disabilities.

“The idea of the American Dream in 2003 was unobtainable for the majority of people,” says Dave Rozza, a math tutor.

The city of Hartford disagreed with their idea of what constitutes a household and sued the group, saying that multiple adults who were not all related couldn’t live together in a single-family dwelling under the city’s zoning laws. The city dropped the case after a year and a half but hasn’t changed its codes, leaving the group in a sort of legal limbo.

Most families make similar calculations involving costs, parenting needs, and how their values are reflected in the living arrangements they choose. For the merged families in Hartford, their choice became a radical declaration of independence from societal expectations, and it’s one small story in an epic housing affordability crisis unfolding across the U.S.

In many ways, this is a continuation of the housing market collapse of 2008, after the mortgage industry took advantage of loose regulations and overextended its lending. A lot of that was driven by Wall Street, which packaged subprime and other loans into exotic financial instruments that concealed the weakness in those debts.

When the financial crash came, it took the housing market with it. A wave of foreclosures arrived—more than 2.3 million properties received foreclosure notices in 2008 alone, according to RealtyTrac, and another 2.8 million in 2009. That was accompanied by home seizures (more than 1 million families lost their homes in 2010), job losses, and the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

A decade later, with major economic indicators on the rebound in many places, the housing crisis has turned into an epidemic of unaffordability: too few homes are available where they’re needed, and those that are, whether for sale or for rent, are increasingly out of reach for people whose incomes have effectively stagnated.

There’s no overall shortage of homes; the affordability challenge is different in each city. According to federal government data, the overall housing market has more than kept up with population growth. What’s happened instead is a split.

In hot markets like the technology centers of the West Coast, competition for housing has driven up both rents and sale prices. Seattle is home to fast-growing Amazon and also the highest annual price increases in the country, 12.86 percent as of January. The median sale price in the city has surpassed $800,000.

But in cities still recovering from the housing market collapse, such as those in the Rust Belt, there are plenty of vacant houses. It’s decent-paying jobs that are scarcer, and many of those vacant houses are still owned by banks that are unlikely to sell until the market turns around. In Detroit, prices are going up at a more modest 7.6 percent per year, but there are still an estimated 25,000 vacant houses in the city that were lost to foreclosure over the years.

After buying the West End house—a single-family dwelling—the group had to battle the city over definitions of family and household. Photo by Chris Marion.

That, topped off with stagnant wages, has resulted in a lack of housing many people can afford either to rent or buy. The average wage for a non-managerial employee at the beginning of 1979 was $22.51 per hour in 2018 dollars. In March 2018, it was $22.44 per hour, essentially flat. In that same 40-year period, housing prices have gone up nearly 50 percent, from a median price of $60,300 ($220,300 in today’s dollars) to $326,800 today.

What Seattle and Detroit share is a large percentage of the population considered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to be cost-burdened: households spending more than 30 percent of income on housing. A study by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University estimated that in the greater Seattle area, 33.4 percent of both rental and owner households fit that description in 2015. In Detroit, 31.4 percent did.

These are not unique situations: Nationwide, 1 in 3 households is spending more than 30 percent of income for a home.

With that kind of math working against them, people have had to get creative.

There is no single solution to the housing equation. As communities grapple with housing costs, what is clear is that cooperation and coordination among government, private developers, the nonprofit community, and individuals at all income levels is required.

Solutions will have to be intensely customized by location. What works in a fast-growing city like Seattle won’t work in a city like Detroit, and what helps build more houses to sell is different from what creates more rental units.

Consider all the collaboration, innovation—and compassion—over the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, a suburb about 12 miles south of Salt Lake City: 56 homes, reserved for adults 55 or older, mostly seniors. Most of them owned their own single- or double-wides, but they had to pay $320 per month as a lot fee—leasing the spots where their homes sit.

Most of the residents are retired and on fixed incomes, says Shirlene Stoven, 81, who has lived there since 1994.

In 2013, the owner of the park sold to a large developer, Ivory Homes. The site is situated between two TRAX light rail stations, and the zoning allowed for dense development.

First, the monthly lot fees went up by $89. Six months later, they went up by another $89.

Stoven learned that Ivory had filed plans for a three-story multifamily building there. “We realized what they were up to, to financially squeeze us out,” Stoven says.

But rather than roll over, Stoven got organized. The Applewood residents formed a homeowners association and began a signature drive to try to stop the development and displacement. They swamped city council meetings with neighbors from the wider community.

There are more renters now than ever before: 43.3 million in 2017, nearly 10 million more than just before the recession, according to Pew Research. Photo by Chris Marion.

And the city listened. In the end, the park was downzoned to 25 units per acre, so Ivory decided to sell it. But the land was still attractive to developers, and the competition drove the purchase price up to $4.8 million.

“I thought, ‘Oh, here we go again,’” Stoven says.

But Stoven, who was elected president of the new association, told their story to the new buyers, who decided to give the residents the opportunity to buy their park for $5 million.

How to raise that kind of money? Stoven connected with ROC USA, a nonprofit that helps mobile home owners transform their parks into resident-owned communities. The Applewood residents formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative and were able to raise the money, much of it from ROC USA and the state’s Olene Walker Housing Loan Fund, and buy the land their homes sit on. The deal closed in February.

Stoven said she’s always been tenacious, and thinks that she won the battle because the developers couldn’t intimidate her. Many of the residents in Applewood are homebound and wouldn’t have been able to mobilize for a fight the way she did.

“That’s why I had to fight for them. Because where would they go?” she says.

They’re paying higher pad fees to help with the purchase. But in doing so, they are preserving their affordable homes for the long term in a rapidly growing area.

Efforts to mitigate the affordability crisis fall into two broad categories: providing more money to people to get them into housing and providing more new housing.

Government, especially the federal government, plays an outsize role in financing below-market-rate housing. Rent subsidies, in the form of Section 8 or Housing Choice vouchers, are limited to low- and very-low-income people. Yet only about 1 in 4 households eligible for housing assistance receives it because of chronic underfunding of HUD programs.

HUD also runs the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which provides incentives for investors to subsidize development of new affordable units. The Community Development Block Grant program also sometimes supports affordable housing projects.

However, the Trump administration has repeatedly floated the idea of eliminating the block grant program, and the LIHTC program may be adversely affected by the massive tax cuts passed by Congress in December. With the corporate tax rate cut from 35 percent to 21 percent, those tax credits just aren’t as valuable, and by some estimates that may translate into a loss of more than 200,000 affordable housing units over the next decade.

“Rental assistance really provides that bedrock of making sure people don’t have to spend a disproportionate amount of their income on rent,” says Janice Elliott, the executive director of the Melville Charitable Trust, a foundation that funds efforts to prevent and reduce homelessness.

“The least little thing and boom!—someone’s lost their home,” Elliott says.

Most people in lower income brackets aren’t in the market to buy a house. Their challenge is finding rental property they can afford.

There are more renters now than ever before: 43.3 million in 2017, nearly 10 million more than just before the recession, according to Pew Research. That rise is driving up prices because developers aren’t building new units fast enough. According to the Urban Institute, for every 100 extremely low-income households, there are only 29 affordable rental units available.

It’s not much easier at higher income levels. Because wages haven’t kept up with housing costs, many more people can’t afford to buy.

And in no state in the country can someone earning the minimum wage afford the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment by working 40 hours a week. Rising homelessness in recent years has been exacerbated by precariously housed people being squeezed out of the housing market altogether. Forestalling that outcome is a challenge for low-income people.

“Homelessness is an indicator not only of what’s happening with people, but it’s also indicative of fundamental problems in the economy,” Elliott says.

On the other end of the spectrum, the city of Seattle has built so much rental housing that rents have flattened out in 2018, says Dan Bertolet, a senior researcher on housing and urbanism at Sightline Institute, a Seattle think tank. But homes for purchase are in shorter supply, with the Northwest Multiple Listing Service noting that inventory is well below the normal range.

“What we see in general is there’s a sort of perfect storm of big societal changes happening, putting pressure on housing and cities,” Bertolet says. Everyone wants to live in the city, and technology companies such as Amazon are minting millionaires at a record pace.

Shirlene Stoven, 81, organized her fellow senior housing residents in the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, and formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative. They fended off developers and were able to work with the city and nonprofits to buy the land their homes sit on. Photo by Austen Diamond.

Shirlene Stoven, 81, organized her fellow senior housing residents in the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, and formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative. They fended off developers and were able to work with the city and nonprofits to buy the land their homes sit on. Photo by Austen Diamond.

It’s a “whole bunch of factors that tell us it makes a lot more sense to put more housing in cities,” Bertolet says.

The greater Seattle area is planning for about 1.8 million more people to move there over the next 30 years, and local policies are aimed at steering much of that expected growth to areas that are already urbanized. But if they all want to buy houses, it’s a competitive market.

“One way we know we’re not keeping up is if you just look at the prices,” Bertolet says.

The city of Seattle has created more than 100,000 jobs since 2010, and a lot of that is fueled by the growth of the well-paying high-tech sector.

“Jobs really are what drives the demand for housing,” Bertolet says.

In hot housing markets like Seattle, which has large single-family neighborhoods with strong neighborhood associations wanting to keep density and growth out, construction hasn’t been able to keep up with the demand. Resistance to density is a hot-button political issue, putting upward pressure on both rent and purchase prices. Even average homes for sale have bidding wars.

But several cities have managed to keep housing prices more manageable simply by allowing developers to build more houses faster, as Sightline reported in 2017. Houston has no traditional zoning in the city, but the cheap prices come at the expense of incredible suburban sprawl. Chicago has enacted policies to speed up permitting and reduce restrictions in zoning. And Montreal’s zoning is dominated by low- and mid-rise apartment buildings. Meanwhile, Seattle has large single-family neighborhoods and a much slower and restrictive development process.

“The fundamental problem is it really is a supply-and-demand problem to a city like Seattle,” Bertolet says.

The result is a housing market like the game musical chairs, only it’s the wealthiest who win when the music stops. In a constrained market, that leaves fewer homes for people with less money. Increasing the overall number of housing units is the first step toward increasing the number of those units that are within reach of the non-rich, Bertolet says.

How to build that additional capacity, whether it’s in the far-flung suburbs or in multifamily buildings in newly up-zoned neighborhoods? Removing barriers to house-sharing could allow for more efficient use of the housing stock available, as the Hartford families have found.

Sightline advocates reducing the cost of building housing to stimulate construction. That includes zoning issues, such as raising building heights, up-zoning single-family neighborhoods, and eliminating parking requirements, which add to building costs and also take up space that could be used for housing. Regulations on building and permitting, Bertolet says, add more to housing costs than most people realize and could be reformed. That will go some way toward filling the gap, but not all the way.

“We don’t think the market will solve this problem all on its own,” Bertolet says. “There will always be a portion that can’t afford to pay for what it costs to build a home.”

Without subsidies, what’s left is people making do and looking for alternatives.

It may be a simple case of finding roommates, an age-old option that’s been rebranded as “co-living” for young urbanites. The Rosenblatt family, the Rozzas, and the rest of their household in Hartford formalized the arrangement by buying their house and forming a limited liability corporation that determines who contributes what toward the mortgage, bills, groceries, chores, all the way down to the Netflix subscription.

The next step up from house-sharing, or co-living, is cohousing, a system of quasi-communal living in separate homes with shared common facilities.

Cohousing developments, however, tend to be composed of no more than a few dozen homes and are often not particularly affordable, in part because of newer construction standards and higher quality materials, and also because they tend to be set up by people of above-average income who aren’t necessarily looking for the cheapest possible housing. Despite a more than 30-year history in the U.S., there are only about 165 established cohousing communities, with another 140 in some stage of formation.

The more affordable option—at least from a resident’s perspective—is a community land trust. By definition it creates permanent affordability by limiting the resale price of homes situated on land owned by the trust. While it does provide affordable housing and protect against gentrification, that comes at the expense of social equity: It functions as a barrier to speculation but prevents the use of housing the way much of the country uses it—as a place to store and generate wealth.

CLTs also run up against financing challenges.

“One misconception about CLTs is that they’re somehow this magic bullet, that they’re outside the system and come with their own resources,” says Melora Hiller, the former CEO of Grounded Solutions Network, a nonprofit consulting company that helps communities set up trusts and other forms of equitable housing.

Getting funding to buy land, build, or renovate houses is often dependent on local government sources using federal funds. Those grants are limited, Hiller says, and CLTs often have to compete for that money with other nonprofit providers of low-income rental housing or homeless housing programs.

And buyers of property in community land trusts still need to qualify for a commercial mortgage. The two federal mortgage guarantors, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are committed to supporting a higher number of loans to low-income Americans, but that’s only after a commercial lender is willing to lend the money up front. “We still need the lenders for the origination before federal programs take them over,” Hiller says.

CLTs also need a lot of capital to start up and then grow. That tends to limit their size and the speed at which they grow. “Nobody’s figured out how to make it work at scale,” Bertolet says.

The latest trend is tiny houses.

Technically a trailer with a roof and walls, tiny houses are increasingly being used for infill development: bare-bones granny flats in the backyards of single-family-zoned neighborhoods or on vacant city-owned lots. The living space typically ranges from 120 to 400 square feet. The smaller sizes often exempt them from needing a building permit.

An estimate from Ryan Mitchell, the founder of The Tiny Life website, puts the number of tiny homes at 10,000 in North America, but there isn’t much documentation to support that figure. The spread of videos and TV shows like “Tiny House Nation” and “Tiny House, Big Living,” though, shows that the movement has tapped a desire among Americans to try to downsize and live more simply.

Yet despite the lower cost, small carbon footprint, and potential for DIY construction, cities and communities have been slow to change their zoning codes to allow tiny homes as infill development or transitional or emergency housing. Most cities, for example, make it illegal to live in a vehicle outside an RV park.

In the end, the biggest bottleneck to building more affordable housing is money.

The National Cooperative Bank is likely the largest financial institution that specifically focuses on lending to community projects like cohousing or other forms of cooperatives.

The NCB reported just under $2.3 billion in assets at the end of 2016, a significant amount for the nonprofit sector. But it’s dwarfed by the commercial banks that drive the national housing market. The largest, Bank of America, has 1,000 times as much under management: $2.3 trillion in assets, including $197.8 billion in residential mortgage loans, according to its 2017 annual report.

While lending for affordable housing is part of many major banks’ portfolios, and community development financial institutions focus on all sorts of lending in distressed communities, alternative housing developers find that commercial banks are less likely to make loans outside traditional markets.

That leaves only one source with the resources to fund the wide variety of solutions necessary, at the scale necessary to address the nationwide problem, and that’s the government.

Another reason the government is an important part of the solution: In the face of market forces and housing scarcity, unlike with other commodities, there is little option not to participate. Everyone needs housing, and it’s not very portable. No solution can address the entire scope of the problem without government involvement.

The Trump administration, however, is cutting back on funding for social safety-net programs, putting many local governments under pressure.

“A local community has to have a local housing trust fund. It has to have money,” Lisa Sturtevant, a Virginia-based housing consultant, says. “It can’t do this through land use and zoning alone.”

For now, a patchwork of foundations and charities try to fill in the gap as best they can.

And where institutions fail, people step up.

The extra-large household in Hartford has been an inspiration to other people willing to challenge city laws and give creative co-living a try.

“We wanted to make it so that other people could do this, too,” Laura Rozza says about their battle with the city.

Rosenblatt says that their group has been approached by some other people interested in forming their own intentional communities, and Rozza says she regularly receives online alerts for communities that are looking at loosening their codes to accommodate alternatives to one-house-one-family norms.

It’s a system that’s worked out well for them, especially with raising children in the house.

“If I don’t have one of my own parents around, I’ll have a lot of other people around to help me with something I need,” says Tessa Rosenfield, who is 13. “Also, I’m never alone, and that’s nice to have all those people around you.”

In choosing to live in community—sharing not just a house, but their lives with each other—they’ve defined a new American Dream. They hope others will follow their model, if not by making the same choice, then by being willing to look beyond traditional boundaries.

“That just makes us intentional, as opposed to others who come together because of blood and do not share values,” Rosenblatt says. “I have one marriage to Josh and another one to each and every other person in the house.”

“It takes a lot of time and energy, like, unspeakable amounts of time and energy. To make that happen and be worth it, you have to really have to want that,” Welch says.

“And the payoff is huge,” Laura Rozza adds.

Matthew Daly and Richard Lardner, Associated Press May 29, 2018

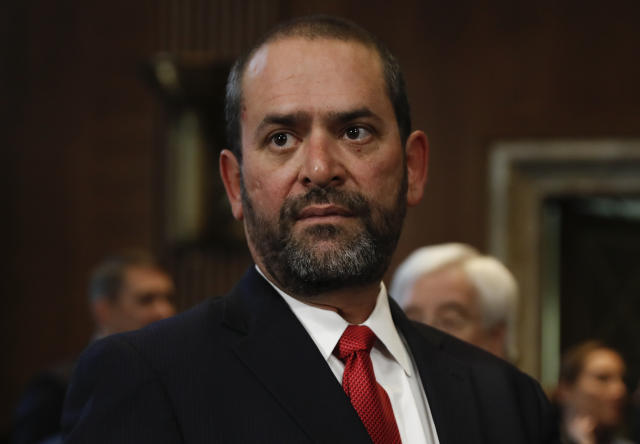

January 19, 2017 photo: Jeff Miller attends then Energy Secretary-designate Rick Perry’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on Capitol Hill in Washington. President Donald Trump has talked frequently about ‘draining the swamp’ of inside dealers in Washington. But lobbyist Jeff Miller might be considered part of the new swamp. Miller, who is a close friend of Energy Secretary Rick Perry, is pushing the administration for a bailout worth billions of dollars for FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt coal and nuclear power company. Miller has earned $3.2 million in just over a year as a lobbyist for clients that include several large energy companies. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

January 19, 2017 photo: Jeff Miller attends then Energy Secretary-designate Rick Perry’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on Capitol Hill in Washington. President Donald Trump has talked frequently about ‘draining the swamp’ of inside dealers in Washington. But lobbyist Jeff Miller might be considered part of the new swamp. Miller, who is a close friend of Energy Secretary Rick Perry, is pushing the administration for a bailout worth billions of dollars for FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt coal and nuclear power company. Miller has earned $3.2 million in just over a year as a lobbyist for clients that include several large energy companies. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Washington (AP) — At a West Virginia rally on tax cuts, President Donald Trump veered off on a subject that likely puzzled most of his audience.

“Nine of your people just came up to me outside. ‘Could you talk about 202?'” he said. “We’ll be looking at that 202. You know what a 202 is? We’re trying.”

One person who undoubtedly knew what Trump was talking about last month was Jeff Miller, an energy lobbyist with whom the president had dined the night before. Miller had been hired by FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt power company that relies on coal and nuclear energy to produce electricity. His assignment: push the Trump administration to use a so-called 202 order — named for a provision of the Federal Power Act — to secure a bailout worth billions of dollars.

Although Trump didn’t agree to the plan — he still hasn’t — for Miller, a president’s public declaration of interest amounted to a job well done.

How a single lobbyist helped carry a long-shot idea from obscurity to the presidential stage is a twisty journey through the new swamp of Trump’s Washington. Rather than clearing out the lobbyists and campaign donors that spend big money to sway politicians, Trump and his advisers paved the way for a new cast of powerbrokers who have quickly embraced familiar ways to wield influence.

Miller is among them. A well-connected GOP fundraiser, he served in the past as an adviser to California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and to Texas Gov. Rick Perry, also a close friend. He ran Perry’s unsuccessful presidential campaign in 2016. And when Trump tapped Perry to lead the Energy Department, Miller shepherded his friend through confirmation, sitting behind him, next to the nominee’s wife, at the Senate hearing.

When Perry came to Washington, Miller did, too. He launched his firm, Miller Strategies, early last year and began lobbying his friend and other Washington officials.

Besides Perry, Miller is close to other Trump-era power players. He is among House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s best friends, their relationship dating back decades to Miller’s days in California. In more recent years, Miller developed a friendship with Vice President Mike Pence adviser Marty Obst.

Obst says the two began working closely together when Perry and Pence held leadership roles at the Republican Governors Association several years ago. “He’s very influential in Washington, a leading fundraiser,” Obst said of Miller in a brief interview.

Now, after 14 months in business, the 43-year-old has collected more than $3.2 million from a roster of clients that includes several of the nation’s largest energy companies, among them Southern Co., a nuclear power plant operator headquartered in Atlanta, and Texas-based Valero Energy, according to federal filings.

Miller also has continued to raise money for GOP politicians. He contributed nearly $37,000 of his own over the past year to Republicans, including Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas and Greg Pence of Indiana, who’s seeking the congressional seat once held by his younger brother, the vice president, according to federal campaign records.

He is an active supporter of America First Action, a pro-Trump super PAC that raised $4.7 million in the first three months of 2018. That work earned him a spot at dinner with Trump, McCarthy and other GOP donors in the upscale City Center complex blocks from the White House.

“What happened to draining the political swamp?” asks Dick Munson with the Environmental Defense Fund, who said he sees FirstEnergy and other coal operators “grasping” for bailouts to solve problems of their own making. “It seems when you don’t have solid arguments, you hire well-paid lobbyists and make huge political contributions.”

Miller declined to comment for this story.

Brian Walsh, president of America First Action, said Miller raises money for the group on a volunteer basis. Miller, who lives in Texas, spent years outside of Washington independently developing an “amazing” network of connections, Walsh said. He described Miller as a “straight shooter” and rejected the notion that he is cashing in on Trump’s election and Perry’s ascension to energy chief.

“He doesn’t play games with people,” Walsh said of Miller.

But Tim Judson, executive director of Nuclear Information and Resource Service, an activist group, called Miller’s involvement in the bailout request the ultimate “Washington swamp” situation.

“We have a special-interest appeal by FirstEnergy, a top lobbyist dining with the president, and that same lobbyist is raising money for a pro-Trump super PAC and asking for ’emergency action’ from someone whose presidential campaign he ran,” Judson said.

Miller registered as a lobbyist in Washington in February 2017, just after Trump took office. He was hired by FirstEnergy in July 2017. Lobbying disclosure records show he was paid to target the highest levels of American government: the White House — to include the offices of Trump and Pence — and Perry’s Energy Department. Miller has earned $330,000 from FirstEnergy since last year, making him one of the company’s highest-paid outside lobbyists.

The coal industry’s top priority at the time was seizing on the campaign promises Trump had made — he pledged repeatedly to bring back coal jobs — to ask for unprecedented federal assistance.

Ohio-based Murray Energy Corp., the nation’s largest privately owned coal-mining company, and its largest customer, FirstEnergy, pushed the Energy Department for an emergency order, a measure typically reserved for war or natural disasters. Among other measures, the intervention would have exempted power plants from obeying a host of environmental laws and would have spent billions to keep coal-fired plants open, an unprecedented federal intervention in the nation’s energy markets.

CEO Robert Murray and Charles Jones, CEO of FirstEnergy’s parent company, met with Trump in West Virginia to discuss the request, informing the president that the power company was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Despite the high-powered lobbying, Perry rejected the request in August, saying the emergency order wasn’t the right mechanism. He offered another option, asking federal energy regulators to approve a plan that would reward nuclear and coal-fired power plants for adding reliability to the nation’s power grid. But the independent Federal Energy Regulatory Commission rejected the plan in January, saying there’s no evidence that past or planned retirements of coal-fired power plants pose a threat to grid reliability.

Soon after, FirstEnergy began pushing anew for the 202. Miller has visited the Energy Department at least twice since June, including on the day Trump delivered a speech on his energy agenda at the agency’s Washington headquarters.

The company argues the emergency order is needed to prevent premature retirement of coal and nuclear plants that “cannot operate profitably under current market conditions.” The proposal would allocate money to subsidize the company and other coal operators — an outcome the company says would avert thousands of layoffs and help ensure reliability of the electric grid up and down the East Coast.

The Ohio-based company filed for bankruptcy in late March, days after announcing it would shut down three nuclear plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania within three years. The announcement followed the planned closure of a West Virginia coal-fired plant, one of a series of closings as the coal and nuclear industries struggle to compete with electricity plants that burn natural gas.

FirstEnergy’s bid for the emergency request is widely opposed by business and environmental groups as an unfair tipping of the scales in favor of faltering energy sources.

An independent wholesaler that oversees the power grid in 13 states and the District of Columbia has said the Eastern grid is in no immediate danger. FirstEnergy can shut down its three nuclear power plants within three years without destabilizing the power grid, according to a report last month from the wholesaler, PJM Interconnection.

Still, the push for a bailout continues.

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., recently suggested that Perry consider using a Korean War-era defense law to prevent the retirement of ailing coal and nuclear units. The Defense Production Act of 1950 is intended to prioritize industries deemed vital to national security. President Harry Truman used the law to cap wages and impose price controls on the steel industry.

FirstEnergy said it supports the premise, although it says it has not specifically urged Perry to use the defense law.

Perry said the administration is looking at the defense law “very closely,” one of several options being considered.

Associated Press writer Steve Peoples contributed to this report.

By Michael Rubinkam, Associated Press May 28, 2018

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a barn that can hold up to 4,800 hogs sits at the Will-O-Bett Farm outside Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the hog operation have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a barn that can hold up to 4,800 hogs sits at the Will-O-Bett Farm outside Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the hog operation have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

Berwick, PA. When the wind blows a certain way, residents know to head inside. Quickly. They claim the stench from an industrial hog farm on the edge of town is unbearable.

The gigantic “finishing” barn confines as many as 4,800 hogs. That many animals produce a lot of waste, and it’s what Will-O-Bett Farm does with the liquid manure — applying tens of thousands of gallons to nearby farm fields — that prompted a nasty legal dispute with neighbors.

Pennsylvania law shields farms from most suits making a nuisance claim, helping Will-O-Bett prevail in the lower courts. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court must now decide whether it will hear the case after plaintiffs filed a last-gasp appeal this month.

“People spent their entire life working to pay the mortgage and they can’t go outside now and sit on their own deck and have a glass of wine because it’s putrid here,” said Malcolm Plevyak, a recycling company owner so upset over the hog farm that he ran for and won local office.

Will-O-Bett’s owner, Paul Dagostin, declined comment, citing the pending litigation. His lawyer, Lou Kozloff, called the plaintiffs’ claims hyperbolic and unsubstantiated in a legal filing that asked the Supreme Court to decline the case. State regulators have found the farm to be in compliance and said it voluntarily implemented an odor-control plan even though it wasn’t legally required.

Industrial farms known as concentrated animal feeding operations allow for more efficient production of beef, pork, poultry, dairy and eggs. They’ve also stoked concerns about animal welfare as well as air and water pollution. Lawsuits are common, including one filed in North Carolina that recently resulted in a federal jury verdict of nearly $51 million — later slashed to $3.25 million — against the hog-production division of Virginia-based Smithfield Foods.

Will-O-Bett, a 63-year-old family farm just outside Berwick, population 10,000, began raising hogs in 2013 under contract for Country View Family Farms, which is part of a conglomerate that includes the Hatfield Quality Meats brand of pork products. The farm fattens them from 60 pounds when they arrive to 270 pounds when they leave for slaughter.

Will-O-Bett stores the manure in a 1.6 million-gallon underground tank. The manure is applied to farm fields as fertilizer in spring and fall. The 40,000-square-foot barn that confines the hogs is ventilated frequently, neighbors say, with 10 gigantic fans pointed in the direction of town. The plaintiffs’ lawsuit says about 1,500 residents live within a mile of the farm, which is also near schools, churches and a hospital.

The complaints began as soon as residents caught the first whiff.

Residents say they’re forced indoors when the breeze carries the odor their way, unable to mow the lawn, tend the garden or use the pool. They say they can’t open their windows or hang their wash out to dry.

“We want to enjoy our property,” said John Molitoris, who lives down the street from Will-O-Bett. “We don’t want to be hostages.”

Molitoris and more than 100 other residents sued the farmers and Country View, but a judge cited the state’s right-to-farm law in summarily dismissing their claims. A state appeals court agreed.

“We do not doubt that the plaintiffs are genuinely aggrieved by the odors associated with the Will-O-Bett’s expanded/altered operation,” Senior Judge Eugene B. Strassburger III wrote for Superior Court in March. “However, our Legislature has determined that such effects are outweighed by the benefit of established farms investing in expansion of agricultural operations in Pennsylvania.”

State regulators, meanwhile, says Will-O-Bett has complied with all regulations. The Department of Environmental Protection has gotten numerous complaints about the farm over the years, but its inspectors have yet to find a single violation. The Department of Agriculture says the farm complies with its odor-management plan.

Neighbors have asked the high court to intervene, a longshot in the best of circumstances. The court accepts a fraction of the appeals it receives.

“I’m not doing it for money,” said Kip McCabe, another plaintiff. “I just want the smell to stop.”

Five years after Will-O-Bett began raising large numbers of hogs, other residents seem to have made their peace with the farm — or at least become resigned to it. The “NO PIG FACTORY’ signs once found on many lawns have mostly disappeared. Most of the original plaintiffs have dropped out of the appeals.

Stacy Banyas said she’s gotten used to the pigs.

“I don’t know that it bothers me that much,” said Banyas, pushing a stroller with her 3-month-old daughter on a night when the springtime air smelled of freshly mown grass, not pig waste. “I don’t know that there’s anything we can do about it, either.”

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a sign opposing an industrial hog farm is displayed at a home in Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the nearby hog farm have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a sign opposing an industrial hog farm is displayed at a home in Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the nearby hog farm have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

Michael Daly May 27, 2018

As we come to Memorial Day with at least the hope of a resolution with North Korea, we should remember U.S. Army Chaplain Emil Kapaun, who as a POW looked more like an eye-patched pirate than a priest, yet is credited with saving literally hundreds of lives with the pure power of spirit.

On a wartime Easter Sunday more than six decades ago, Kapaun caused an entire valley to fill with the voices of his fellow prisoners singing “America the Beautiful.” He posthumously received the Medal of Honor and is presently being considered for sainthood. The nephew who accepted the belated medal on his behalf in 2013 is certain Kapaun would be particularly pleased that there is now at least a chance of peace at long last.

“Wouldn’t that be something?” the nephew, Ray Emil Kapaun, told The Daily Beast on Friday. “That would be incredible. Without a doubt that would be good.”

At 61, the nephew is too young to have ever met his fallen uncle, but came to know him through the stories he heard while growing up. Soldiers who credited Father Kapaun with saving their lives told him that the Medal of Honor citation offers only a partial account of his heroism:

“Chaplain Emil J. Kapaun distinguished himself by acts of gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty while serving with the 3d Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division during combat operations against an armed enemy at Unsan, Korea, from November 1-2, 1950. On November 1, as Chinese Communist Forces viciously attacked friendly elements, Chaplain Kapaun calmly walked through withering enemy fire in order to provide comfort and medical aid to his comrades and rescue friendly wounded from no-man’s land.”

The priest had been smoking a pipe earlier in the battle and a bullet had suddenly left him with just the stem in his mouth. He kept on, carrying one wounded soldier to safety and then immediately returned to direct danger to save another. He would pause amidst bullets and shrapnel to bless the dead.

“Though the Americans successfully repelled the assault, they found themselves surrounded by the enemy,” the citation continues. “Facing annihilation, the able-bodied men were ordered to evacuate. However, Chaplain Kapaun, fully aware of his certain capture, elected to stay behind with the wounded.”

Kapaun remained with those who were too badly injured to withdraw.

“After the enemy succeeded in breaking through the defense in the early morning hours of November 2, Chaplain Kapaun continually made rounds, as hand-to-hand combat ensued. As Chinese Communist Forces approached the American position, Chaplain Kapaun noticed an injured Chinese officer amongst the wounded and convinced him to negotiate the safe surrender of the American Forces.”

Kapaun had just become a prisoner when he saw a North Korean soldier step up to an American who lay seriously wounded in a ditch. The enemy soldier aimed his weapon at the American’s head.

“Shortly after his capture, Chaplain Kapaun, with complete disregard for his personal safety and unwavering resolve, bravely pushed aside an enemy soldier preparing to execute Sergeant First Class Herbert A. Miller.”

The citation notes that Kapaun thereby “saved the life of Sgt. Miller,” but does not go on to report what immediately followed. The priest then picked up Miller and carried him for miles as the enemy force marched the captured Americans away from the front lines.

When Kapaun grew weary, he helped Miller hop on his one good leg for a time. Kapaun then resumed carrying him. They eventually reached a schoolhouse and were joined by another group of prisoners. The others included Lt. Mike Dowe, who would remember first encountering Kapaun during the ensuing death march, in which guards shot any stragglers.

“Who are you?” Dowe asked.

“Kapaun,” the chaplain said.

“Father Kapaun, I have heard about you.”

“Well, don’t tell my bishop.”

Kapaun urged on people who otherwise might have just given up.

“Maintaining a will to live is everything,” Dowe told The Daily Beast on Sunday. “You can just decide you don’t want to fight it any more and be dead the next morning. It was actually that will that Father Kapaun instilled in so many people.”

After four or five days, they came to a valley. Kapaun and Dowe were lodged in a separate officer’s compound on a hilltop surrounded by a wood fence. Kapaun led those of all faiths in prayer. He also set to fashioning a pot by hammering a piece of meat with a rock. He was partially blinded when a sliver of tin flew into one of his eyes.

“It didn’t bother him, he just put a patch over it and that was it,” Dowe would recall.

Kapaun would rise before dawn in subzero cold and make a fire and heat water in the pot. He would pour the hot water through a sock in which he had stuffed some beans that were nothing close to coffee.

“Hot coffee!” Kapaun would announce. “Good morning everyone! Hot coffee!”

Dowe would recall, “You just can’t imagine how good that tasted. Kapaun’s coffee.”

With his eye patch and a stocking cap, Kapaun looked nothing like a priest as he moved about the camp.

“He looked more like a pirate,” Dowe would remember. “But, when he would walk into some place, a whole new aura would just descend on it.”

Kapaun would slip out at night to minister to the enlisted men, going from to hut, aiding the sick, giving blessings and encouragement. He was a Catholic priest who embraced all faiths and encouraged Jews and Protestants to join in saying the rosary. He also would bring any food he was able to forage or steal from their captors. He would encourage hoarders to share with others.