HANOI, Vietnam — President Donald Trump, who arrived here on Tuesday for a nuclear summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, is desperate for a win.

At home, the fallout from special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into his campaign’s ties to Russia and possible obstruction of justice continues to spread. Trump’s domestic agenda is still suffering the aftereffects of a 35-day government shutdown. And he’s fighting Congress and more than a dozen states over his plan to transfer billions of federal dollars to build a wall on the U.S. border with Mexico.

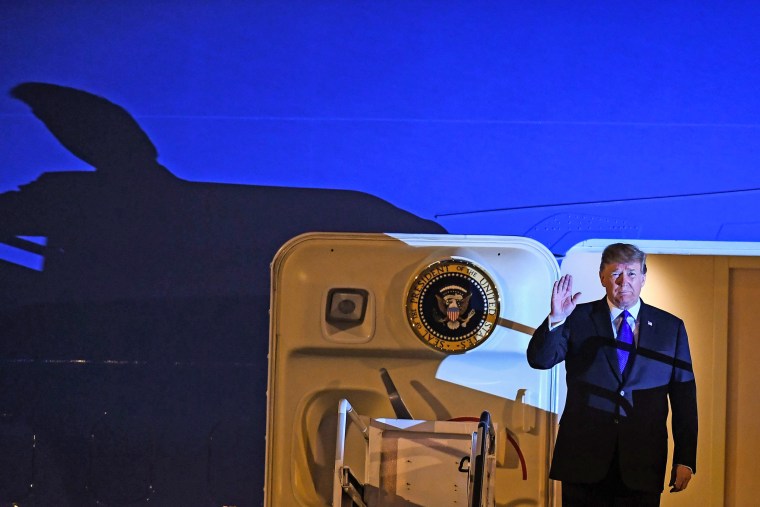

It appears that Trump, who touched down on Air Force One at Hanoi’s Noi Bai International Airport shortly before 9 a.m. ET, is likely to be spared the indignity of Mueller’s final report being filed while he is abroad, but Michael Cohen, his former lawyer, is set to testify for three days, beginning Tuesday, on Capitol Hill about the president’s business dealings, his efforts to influence the 2016 election and his level of compliance with tax laws.

Trump’s arrival was greeted with a red carpet, a 26-man Vietnamese honor cordon and a bouquet of flowers, which was handed to him by a Vietnamese woman.

Trump’s arrival was greeted with a red carpet, a 26-man Vietnamese honor cordon and a bouquet of flowers, which was handed to him by a Vietnamese woman.

The president shook hands with a delegation of Vietnamese and U.S. diplomatic officials, before giving a quick wave to the assembled media and ducking into his limousine — “The Beast” — for the ride to his hotel. He did not have any public events planned until Wednesday morning in Hanoi, where the time is 12 hours ahead of Washington.

In short, Trump needs to put some points on the board.

The president and Kim are set to have dinner Wednesday before their summit meeting Thursday. Both the dinner and the summit will take place at the Sofitel Legend Metropole Hanoi, White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders said.

Trump’s political opponents say they’re worried that his domestic concerns may play a decisive role in Hanoi this week, pushing him into grasping for unwise bargains with North Korea.

“Given Trump’s aversion to briefings and policy papers, the Kim summit was always a dubious enterprise with high risks, but Trump’s disastrous last two months weaken his already unsteady hand at the negotiating table,” said Rep. Gerry Connolly, D-Va., a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. “Kim Jong Un knows how to exploit weakness when he sees it.”

And if the past is any guide, the president may find a way to declare victory — or simply to say that he’s struck another agreement with Kim — whether or not he emerges with a concrete plan to halt Pyongyang’s ongoing development of nuclear weapons.

There is concern in Washington foreign policy circles, among both Democrats and Republicans, that in his hunger to chalk up a public win, Trump — who has already boasted that his diplomatic efforts with regard to the regime have been Nobel Prize nomination-worthy— could give up too much and get too little in return.

Sen. Cory Gardner, R-Colo., the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s Subcommittee on East Asia, the Pacific, and International Cybersecurity Policy, said in response to emailed questions from NBC News that he hopes the president will be firm with Kim about demanding complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization before the U.S. decreases pressure on North Korea.

“The administration should make clear to Pyongyang that the only way we will dismantle the U.S. and international sanctions regime is when Pyongyang completely dismantles every single nut and bolt of its illicit weapons programs — not a minute earlier,” he said.

The process this time has to move beyond the generalities of the Singapore summit, said Laura Rosenberger of the German Marshall Fund, a former foreign policy adviser to Hillary Clinton.

When he met with Kim in Singapore, Trump heralded an agreement to work toward denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, but U.S. intelligence officials have said that while Pyongyang has taken steps to dismantle some of its nuclear capabilities, it has not demonstrated that it is willing to abandon its program.

On Twitter, he countered Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats’s public assessment that “North Korea is unlikely to give up all of its nuclear weapons and production capabilities” by saying there’s a “decent chance” of denuclearization.

And in the run-up to the latest summit, Trump has appeared to lower the bar for claiming victory out of the event by tempering expectations for a quick and comprehensive deal on denuclearization, saying last week that he is in “no rush” to make that happen.

“I have no pressing time schedule,” he said.

North Korea’s wish list includes not just the removal of crippling U.S. and international economic sanctions — Trump has tried to sell Kim on the idea that his nation could one day be a Pacific Rim powerhouse — but also the removal of U.S. troops from South Korea. American forces have been stationed there since the unofficial end of the Korean War nearly 70 years ago.

Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., a member of the Foreign Relations Committee, told NBC News in response to emailed questions that he is supportive of diplomatic efforts to resolve the standoff with North Korea but has reservations about what the president’s track record means for this summit.

“I’m concerned that President Trump will again be quick to make concessions without getting anything in return,” he said, pointing to a decision to cancel joint military exercises with South Korea after June’s summit. “At Hanoi, the president needs to demand North Korea disclose details of its current stockpiles and capabilities, then agree on a clear, shared definition of denuclearization including benchmarks to show verifiable progress toward that goal.”

On that score — the idea that success means a real process for denuclearization rather than an announced deal that ends up allowing Pyongyang to continue to quietly develop its weapons program — Republicans and Democrats in Congress appear to be in agreement.

But the political calculation for Trump remains the same — which means that a declaration of victory, no matter the policy achievement, is far more likely than a decision to walk away from another detail-free offer. For a president facing both turmoil at home and pressure abroad born of his failure to extract concessions at the last Kim summit, failure — or, at least, the appearance of failure — may not be an option.

Trump’s arrival was greeted with a red carpet, a 26-man Vietnamese honor cordon and a bouquet of flowers, which was handed to him by a Vietnamese woman.

Trump’s arrival was greeted with a red carpet, a 26-man Vietnamese honor cordon and a bouquet of flowers, which was handed to him by a Vietnamese woman.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell says the budget deficit is “very disturbing.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell says the budget deficit is “very disturbing.”