VOX

Scott Pruitt is slowly strangling the EPA

The unprecedented regulatory slowdown and rollbacks at the Environmental Protection Agency.

By Umair Irfan January 29, 2018

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58490215/scott2.0.jpg) Javier Zarracina/Vox

Javier Zarracina/Vox

The mandate of the head of the Environmental Protection Agency is to protect human health and enforce environmental regulations.

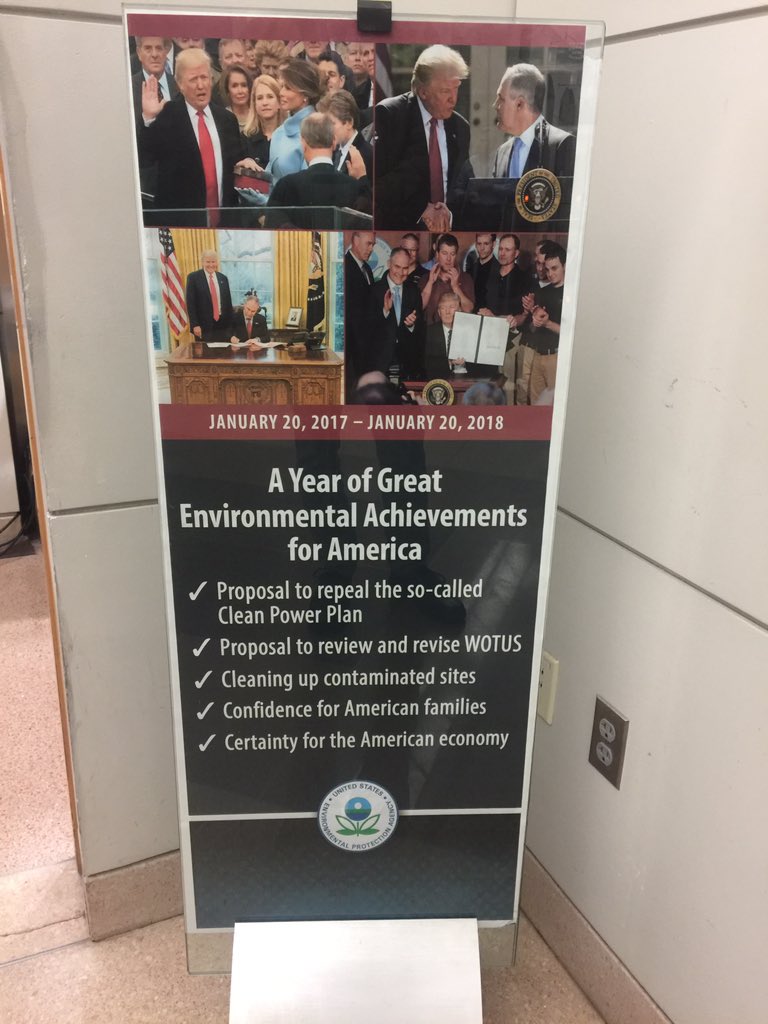

Yet since he was confirmed last February, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has worked to stall or roll back this core function of his agency, efforts he’s now celebrating with posters:

Eric Lipton @EricLiptonNYT: EPA has put these posters up at agency buildings. Celebrating regulatory rollbacks.

He’s also taken some highly unusual, even paranoid, precautions, armoring himself with a 24/7 security detail, building a $25,000 secret phone booth in his office, spending $9,000 to sweep his office for surveillance bugs, and hiding his schedule from the public. When one employee turned one of the celebratory posters around, Pruitt assigned a worker to look through security camera records to see who did it, Newsweek reported.

Pruitt’s posters are a list of the regulatory rollbacks he’s delivered to his allies in coal, oil, gas, and chemicals industries. These gifts include the reversal of a ban on chlorpyrifos, a pesticide linked to developmental problems in children.

Some of the biggest changes Pruitt has made at the EPA have come by not doing anything at all. He’s steering the EPA’s work at an agonizingly slow pace, delaying and slowing the implementation of laws and running interference for many of the sectors EPA is supposed to regulate.

With more staff and funding cuts looming, even fewer toxic chemicals and other environmental hazards will be measured, and the statues that protect against them won’t be enforced.

“People will get sick and die,” Christine Todd Whitman, who served as EPA administrator under President George W. Bush, told Vox. “It’s that simple.” Some 230,000 Americans already die each year due to hazardous chemical exposures. “You stop enforcing those regulations and that number will go way up,” she said.

Chaos at the White House and on Capitol Hill has provided Pruitt cover to quietly position himself, his critics argue, as the greatest threat to the EPA in its entire existence. But some lawmakers and the courts are starting to catch onto him. Since the EPA’s inception, it’s been the judiciary that’s again and again beaten back attempts to undermine the agency from the inside. This year is again shaping up to be momentous.

States are now suing to block Pruitt’s regulatory changes, and federal judges are starting to force him to speed up. Pruitt will have to choose between knock-down, drag-out legal fights to deliver for his allies in industry or fold and grudgingly enforce environmental rules. Whatever he decides, Congress, courts, industry, and activists will be watching.

There’s a massive, unprecedented slowdown going on across the EPA

Pruitt can’t simply repeal all the rules he doesn’t like, so he’s had to embrace a different strategy: stall.

Much of EPA’s work is governed by statute, so dismantling most environmental regulations requires an arduous rule-making process that requires public comments, as well as new rules to comply with the law. The whole endeavor is inevitably beset by lawsuits at every step.

“In order to roll back rules, you have to not just have a different policy inclination,” said former EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy, who worked under President Barack Obama. “If you have a final rule, you actually have to find a flaw with the rule, you have to justify it.”

By stalling, Pruitt can effectively shift policy by doing nothing. If he leaves regulations in limbo or delays their implementation, industries get relief from environmental rules while the EPA retains plausible deniability. The result is a drastic slowdown in the pace of work at an agency that faces a constant churn of new rules, regulations, enforcement actions, and lawsuits that affect the health, safety, and livelihoods of millions of Americans.

Here are some of the environmental rules, actions, and proposals that have become mired in the morass:

- The EPA announced it was seeking a two-year delay in implementing the 2015 Clean Water Rule, which defines the waterways that are regulated by the agency under the Clean Water Act.

- In May, the EPA dialed backtracking the health impacts of more than a dozen hazardous chemicals at the behest of a Trump appointee at the agency, Nancy Beck.

- The agency has said nothing about counties that failed to meet new ozone standards by an October 2017 deadline and now face fines.

- Environmental law enforcement has declined. By September, the Trump administration launched 30 percent fewer cases and collected about 60 percent fewer fines than in the same period under President Obama.

- The EPA punted on regulations on dangerous solvents like methylene chloride, a paint stripper, that were already on track to be banned, instead moving the process to “long term action.”

- The EPA asked for a six-year schedule to review 17-year-old regulations on lead paint.

- The implementation date of new safety procedures at chemical plants to prevent explosions and spills was pushed back to 2019.

- Pruitt issued a directive to end “Sue & Settle,” a legal strategy that fast-tracks settlements for litigation filed against the EPA to force the agency to do its job. The agency will spend more time in courts fighting cases that it’s likely to lose.

- The agency’s enforcement division now has to get approval from headquarters before investigating potential violations of environmental regulations, slowing down efforts to catch violators of laws like the Clean Water Act.

“The problem at EPA right now is there is a chilling effect on enforcement,” Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, told E&E News.

Even programs Pruitt ostensibly liked are suffering under his leadership, like the cleanup of highly contaminated Superfund sites. In an interview with CBS, Pruitt said he’s aiming to take 27 to 30 sites fully or partially off the list this year. He’s also threatened to cut agency funds for pursuing polluters to make them pay for cleaning up these locations.

Pruitt has taken credit for removing seven Superfund sites from the list, but that work started years before he got to the agency and was completed before he took office, as Timothy Cama reported for The Hill.

The Superfund cleanup program is now run by Albert Kelly, an Oklahoma banker who was banned for life from the industry after receiving a $125,000 federal fine and has no experience in environmental remediation. The Intercept reported that Pruitt received loans from Kelly’s bank.

This is not to say that Pruitt isn’t deregulating the old-fashioned way as well. Under his leadership, the EPA already has tried to roll back at least 19 environmental regulations, from undoing proposed greenhouse gas regulations to relaxing standards for ozone pollution. (The EPA did not respond to requests for comment for this article.)

Just last week, the EPA announced it was going to allow some toxic chemical polluters to be held to a lower standard under the Clean Air Act, allowing them to increase emissions of substances like mercury, lead, and dioxin. The White House’s infrastructure plan would block the EPA from evaluating and rejecting projects based on their Environmental Impact Statements, the Washington Post reported.

“He is much more organized, much more focused than the other Cabinet-level officials, who have not really taken charge of their agencies,” Richard Lazarus, a professor of environmental law at Harvard University, told the New York Times. “Just the number of environmental rollbacks in this time frame is astounding.”

Losing the environmental protections established by the EPA could harm millions of Americans

The EPA is essentially an environmental public health agency. Its regulations directly affect millions of Americans as it diagnoses ailments in the air, water, and soil, to name a few, and prescribes solutions.

It has had a pretty great track record.

The Clean Air Act, for example, reduced conventional air pollutants by 70 percent since 1970. Substances like ozone, carbon monoxide, and lead have dangerous consequences for human health like heart attacks, strokes, and respiratory arrests.

According to one estimate, the legislation prevents 184,000 premature deaths each year and has saved $22 trillion in health care costs over a period of 20 years.

But enforcing these rules bears a cost as well, and critics say that continuing to make many of these regulations more stringent is regulatory malpractice since these rules are reaching diminishing returns, costing businesses and individuals more and more to comply with them. This is the main rationale for the White House’s aim to cut back on “job-killing”regulations.

Staff cuts and unfilled positions may be part of Pruitt’s strategy

It’s hard to tell whether the lingering vacancies at the EPA are a deliberate effort by Pruitt to avoid the congressional scrutiny that comes with every new appointee, or a consequence of the dysfunction inside the agency and the White House.

EPA has only filled five out of 14 positions that require Senate approval a year after Trump took office. Throughout the federal government, of the 624 positions that require congressional confirmation, only 242 slots have been filled, and 244 jobs don’t have any nominee at all.

Trump has suggested that many of these vacancies may never be filled.

“I’m generally not going to make a lot of the appointments that would normally be —because you don’t need them,” he told Forbes in November. “I mean, you look at some of these agencies, how massive they are, and it’s totally unnecessary. They have hundreds of thousands of people.”

The remaining EPA officials are now further constrained since the Federal Vacancies Reform Act deadline expired last November. The law prevents interim workers from performing many of their duties 300 days after inauguration.

“On Day 301, whenever that day might occur for a particular office, the office would be designated vacant, for purposes of the Vacancies Act, and only the head of the agency would be able to perform the functions and duties of that vacant office,” according to the Congressional Research Service.

That means every decision that would normally fall to a lower ranking official has to be kicked up to the top office. For an agency like EPA, that means actions on monitoring the environment, pursuing polluters, and filing lawsuits end up bottlenecked at the desk of Pruitt, who has shown little appetite for fulfilling the agency’s mandates to begin with.

More than 700 employees have left the agency since it began to try to buy out more than 1,200 workers began last year. And more staff cuts are likely still in store, though they may not be as severe as the 20 percent workforce cut requested in the White House’s initial budget.

Even Pruitt’s allies are perturbed by the EPA’s slow walking

Pruitt’s tenure leading the EPA has enraged environmental activists, but some of his deregulation allies are unhappy with the pace of work and staffing vacancies at the agency too.

Myron Ebell, who leads the Center for Energy and Environment at the Competitive Enterprise Institute and led Pruitt’s transition team at the EPA, warned that not having enough staff in place means that the agency will miss statutory deadlines on regulations, leaving it open to further lawsuits that will sap time and money that could otherwise go toward permanently shrinking the scope of the agency.

“I started complaining, ‘Where are the nominees?’ in March,” Ebell said. “I think over time, this is going to catch up with them. They’re going to have failures and obstacles if they don’t have people in play.”

Another factor, according to Ebell, is that many of the career civil servants at the EPA are not on board with Pruitt, offering less-than-enthusiastic support for the Back to Basics agenda.

“The acting general counsel at EPA is a very competent lawyer and he’s a very nice guy but he’s not going to help Scott Pruitt implement his agenda,” Ebell said. “He’s going to slow walk that.”

This is dimming the prospects for rolling back many of the big prizes for anti-regulation Republicans like Pruitt, like undoing the 2009 endangerment finding for carbon dioxide, EPA’s legal basis for regulating greenhouse gases. These repeals stand to be long, messy fights that cut across law and science.

Many of these regulations took years to put together and will require years to take apart, endeavors that would likely not resolve until well into President Trump’s second term.

“It’s very clear to me that there’s no real intent to redo these things because there’s not a schedule to do these things, and it takes years for a process to revise these rules,” said former administrator McCarthy.

Instead, it seems the EPA is working to prevent the existing greenhouse gas regulations from going into effect as it scrambles to come up with a replacement rule for greenhouse gases by 2019.

Pruitt’s allies’ concern is that without getting these rollbacks enshrined in law, many of EPA’s environmental regulations could snap back into place under a future administration.

While the executive branch is slowing down environmental regulations, it’s speeding up judicial nominations. Many of these new judges are expected to rule on Pruitt’s agenda.

Pruitt, for his part, may be padding his resume for a run for office. He has demurred when asked about his political ambitions, but Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin hits her term limit in 2018, and Oklahoma Sen. James Inhofe plans to retire in 2020. He shot down swirling rumors that he may even be angling for the post of US attorney general should Jeff Sessions step down.

The courts are losing their patience with the agency and are now forcing Pruitt’s hand

Federal agencies like the EPA have broad license to interpret law. Under the Chevron doctrine, courts defer to agencies to interpret statutes on issues that Congress hasn’t addressed head-on.

Pruitt described his approach as paring back EPA’s regulations down to the bare minimum authorized by Congress.

“We aren’t deregulating,” he told the National Review. “We’re regulating in accordance with the law.”

However, federal courts don’t agree and are no longer deferring to the new administration. Courts have already blocked the EPA’s efforts to suspend rules on methane emissions and denied the EPA’s request to spend years researching lead paint, instead giving the agency 90 days to come up with a new regulation.

“I think you’re going to see courts get more involved in the work of the agency,” said former EPA general counsel Avi Garbow, who served under President Obama. “That judicial patience cannot be counted on forever.”

Others are taking a page from Pruitt’s old playbook. Already eight states are suing EPA for failing to expand ozone regulations. The EPA has set a target date of April 30 for designating areas of the country that are not meeting the new, stricter ozone standard.

In January 17 interview with CBS, Pruitt said that ozone is something “we most definitely have to regulate.” Michael Honeycutt, the new chair of EPA’s Science Advisory Board, said cutting ozone regulations would have a “negative health benefit.”

Meanwhile, other states are suing the department for not controlling air pollution moving across state lines. Some of the scientists who were ousted from the EPA’s advisory boards are now suing the agency, arguing that their removal violates the Federal Advisory Committee Act. Public lawsuits are also going forward to try to force the agency’s hand to fight climate change.

There are also some regulations Pruitt supports. He wants to remove lead from all drinking water in the United States in 10 years and has started taking comments on revising rules for water pipes. He also wants to control leaks of methane, the primary component in natural gas and a potent greenhouse gas.

All the while, lawmakers are also growing increasingly suspicious about Pruitt’s activities and are launching investigations. Michael Dourson, a former chemical industry consultant who was nominated to lead the EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, withdrew his name from consideration after facing stiff opposition from Congress.

Senate Democrats are preparing to grill Pruitt when he testifies this week before the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee. They are already putting together their agenda for the EPA administrator should they clinch control of the chamber this fall.

This means that in the coming year, the EPA will have to speed up its work as a regulator or face stiff legal consequences. “I do not think the agency is capable of replicating in 2018 the same degree of affirmative regulatory output that we saw in 2017,” Garbow said.

The laws that govern the EPA require action, and whether those demands come from Congress, the courts, or constituents, the agency needs to produce results that stand up to legal challenges from all sides on a deadline, Garbow said.

The goal is not just to give the regulatory certainty that industries crave, but to protect American lives. Pruitt may soon find out that doing nothing, or even very little, is not an option.

Got a tip or idea for stories about the EPA we should pursue? Contact Umair at umair@vox.com, or on Keybase at umairfan.

NEXT UP IN ENERGY & ENVIRONMENT

- Reckoning with climate change will demand ugly tradeoffs from environmentalists — and everyone else

- The Trump administration is lifting key controls on toxic air pollution

- We know where the next big earthquakes will happen — but not when

- The trouble with Trump leaving climate change to the military

- Trump’s new solar tariff to protect US manufacturers will hurt installers

- The government shutdown is sowing confusion at environmental and science agencies