Esquire

The Drugging of the American boy

Archives: By Ryan D’Agostino March 27, 2014

By the time they reach high school, nearly 20 percent of all American boys will be diagnosed with ADHD. Millions of those boys will be prescribed a powerful stimulant to “normalize” them. A great many of those boys will suffer serious side effects from those drugs. The shocking truth is that many of those diagnoses are wrong, and that most of those boys are being drugged for no good reason—simply for being boys. It’s time we recognize this as a crisis.

The Drug Enforcement Administration classifies stimulants as Schedule II drugs, defined as having a “high potential for abuse” and “with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence.” (According to a University of Michigan study, Adderall is the most abused brand-name drug among high school seniors.) In addition to stimulants like Ritalin, Adderall, Vyvanse, and Concerta, Schedule II drugs include cocaine, methamphetamine, Demerol, and OxyContin.

According to manufacturers of ADHD stimulants, they are associated with sudden death in children who have heart problems, whether those heart problems have been previously detected or not. They can bring on a bipolar condition in a child who didn’t exhibit any symptoms of such a disorder before taking stimulants. They are associated with “new or worse aggressive behavior or hostility.” They can cause “new psychotic symptoms (such as hearing voices and believing things that are not true) or new manic symptoms.” They commonly cause noticeable weight loss and trouble sleeping. In some children, some stimulants can cause the paranoid feeling that bugs are crawling on them. Facial tics. They can cause children’s eyes to glaze over, their spirits to dampen. One study reported fears of being harmed by other children and thoughts of suicide.

Imagine you have a six-year-old son. A little boy for whom you are responsible. A little boy you would take a bullet for, a little boy in whom you search for glimpses of yourself, and hope every day that he will turn out just like you, only better. A little boy who would do anything to make you happy. Now imagine that little boy—your little boy—alone in his bed in the night, eyes wide with fear, afraid to move, a frightening and unfamiliar voice echoing in his head, afraid to call for you. Imagine him shivering because he hasn’t eaten all day because he isn’t hungry. His head is pounding. He doesn’t know why any of this is happening.

Now imagine that he is suffering like this because of a mistake. Because a doctor examined him for twelve minutes, looked at a questionnaire on which you had checked some boxes, listened to your brief and vague report that he seemed to have trouble sitting still in kindergarten, made a diagnosis for a disorder the boy doesn’t have, and wrote a prescription for a powerful drug he doesn’t need.

If you have a son in America, there is an alarming probability that this has happened or will happen to you.

The Diagnosis

6.4 million children between the ages of four and seventeen have been diagnosed with ADHD by high school; nearly 20% of all boys will have been diagnosed with ADHD (a 37% increase) since 2003.

On this everyone agrees: The numbers are big. The number of children who have been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—overwhelmingly boys—in the United States has climbed at an astonishing rate over a relatively short period of time. The Centers for Disease Control first attempted to tally ADHD cases in 1997 and found that about 3 percent of American schoolchildren had received the diagnosis, a number that seemed roughly in line with past estimates. But after that year, the number of diagnosed cases began to increase by at least 3 percent every year. Then, between 2003 and 2007, cases increased at a rate of 5.5 percent each year. In 2013, the CDC released data revealing that 11 percent of American schoolchildren had been diagnosed with ADHD, which amounts to 6.4 million children between the ages of four and seventeen—a 16 percent increase since 2007 and a 42 percent increase since 2003. Boys are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed as girls—15.1 percent to 6.7 percent. By high school, even more boys are diagnosed—nearly one in five.

Almost 20 percent.

And overall, of the children in this country who are told they suffer from attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, two thirds are on prescription drugs.

And on this, too, everyone agrees: That among those millions of diagnoses, there are false ones. That there are high-energy kids—normal boys, most likely—who had the misfortune of seeing a doctor who had scant (if any) training in psychiatric disorders during his long-ago residency but had heard about all these new cases and determined that a hyper kid whose teacher said he has trouble sitting still in class must have ADHD. That among the 6.4 million are a significant percentage of boys who are swallowing pills every day for a disorder they don’t have.

On this, too, everyone with standing in this fight seems to agree.

But on the subject of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, that is where the agreement ends.

For example: Doctors, parents, and therapists give a lot of different explanations for the sharp rise. Increased awareness—that’s a big one. We know more now. Other possibilities put forth: Too many video games. Too much refined sugar. Pharmaceutical companies pushing ADHD drugs. Lack of gym classes at schools. All of these factors are cited. And people have a lot of different ideas about what to do for the children who receive these diagnoses. Many believe that medicine should be the first treatment, either combined with behavioral therapy or not. Others feel that drugs should be a last resort after making every other alleviative effort you can find or think of, from hypnosis to herbal treatments to neurofeedback.

Given today’s prevailing pharmaceutical culture, clinicians who believe that drugs should never be used to treat ADHD in children are very much in the minority. Marketing is powerful, and blockbuster drugs like Ritalin are big business. Business booms, market share grows when scripts are written, and countercultural doctors and therapists who advocate caution and who believe that diagnoses are made too easily—doctors and therapists who preach alternatives to drugs—are finding themselves the butt of jokes.

But more about them shortly.

The United States government first collected information on mental disorders in 1840, when the national census listed two generally accepted conditions: idiocy and insanity. A century later, psychiatrists knew more. They had options when making diagnoses, and by the 1940s difficult kids were classified as “hyperkinetic.” Other terms would follow, like minimal brain dysfunction. In 1955, there came a pill doctors could prescribe for these children to temper their hyperactivity and make them behave more like “normal” children. It was a stimulant, so called because it heightened the brain’s utilization of dopamine, which can improve attention and concentration. The active ingredient was a highly addictive compound called methylphenidate. The drug was called Ritalin.

By 1987, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) had settled on a more refined name for a disorder among children who exhibited the same set of symptoms, including trouble concentrating and impulsive behavior: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD. At the time, in American schools, it was still considered unusual for a child to take Ritalin. It was, frankly, considered weird.

Today, it has simply become a default method for dealing with a “difficult” child.

“We are pathologizing boyhood,” says Ned Hallo-well, a psychiatrist who has been diagnosed with ADHD himself and has cowritten two books about it, Driven to Distraction and Delivered from Distraction. “God bless the women’s movement—we needed it—but what’s happened is, particularly in schools where most of the teachers are women, there’s been a general girlification of elementary school, where any kind of disruptive behavior is sinful. What I call the ‘moral diagnosis’ gets made: You’re bad. Now go get a doctor and get on medication so you’ll be good. And that’s a real perversion of what ought to happen. Most boys are naturally more restless than most girls, and I would say that’s good. But schools want these little goody-goodies who sit still and do what they’re told—these robots—and that’s just not who boys are.”

Especially when they’re young. One of the most shocking studies of the rise in ADHD diagnoses was published in 2012 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. It was called “Influence of Relative Age on Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children.” Nearly one million children between the ages of six and twelve took part, making it the largest study of its kind ever. The researchers found that “boys who were born in December”—typically the youngest students in their class—”were 30 percent more likely to receive a diagnosis of ADHD than boys born in January,” who were a full year older. And “boys were 41 percent more likely to be given a prescription for a medication to treat ADHD if they were born in December than if they were born in January.” These findings suggest, of course, that an errant diagnosis can sometimes result from a developmental period that a boy can grow out of.

And there are other underlying reasons for the recent explosion in diagnoses. Stephen Hinshaw, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and the editor of Psychological Bulletin, the research publication of the American Psychological Association, presents evidence in a new book that ADHD diagnoses can vary widely according to demographics and even education policy, which could account for why some states see a rate of 4 percent of schoolchildren with ADHD while others see a rate of almost 15 percent. Most shocking is Hinshaw’s examination of the implications of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which gave incentives to states whose students scored well on standardized tests. The result: “Such laws provide real incentive to have children diagnosed and treated.” Children with ADHD often get more time to take tests, and in some school districts, tests taken by ADHD kids do not even have to be included in the overall average. “That is, an ADHD diagnosis might exempt a low-achieving youth from lowering the district’s overall achievement ranking”—thus ensuring that the district not incur federal sanctions for low scores.

In a study of the years between 2003 and 2007, the years in which the policy was rolled out, the authors looked at children between ages eight and thirteen. They found that among children in many low-income areas (the districts most “targeted” by the bill), ADHD diagnoses increased from 10 percent to 15.3 percent—”a huge rise of 53 percent” in just four years.

The Consequences

48% of subjects of one study who took ADHD medications experienced side effects like sleep problems and “mood disturbances.” In another, 6% of children suffered psychotic symptoms, including thoughts of suicide.

Source: Psychiatry, April 2010; The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, October 1999.

And yet among many of the people interviewed for this story, the most common explanation for the staggering increase in diagnoses is that doctors know more now. Great strides have been made. “I don’t think there’s an epidemic of new cases,” says Mario Saltarelli, a neurologist and the senior vice-president of clinical development at Shire, which manufactures Adderall and Vyvanse. (Since our interview, he has left the company.) “It’s always been there. It’s now more appropriately understood and recognized.” Instead of lumping together all the kids with high energy and bad behavior and calling them hyper, many experts say, doctors can identify the children who exhibit the symptoms specific to ADHD and treat them accordingly. “We were paying attention,” says Jeffrey Lieberman, the president of the American Psychiatric Association and chairman of psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center. “We [now] have reliable descriptions and the means of diagnosing.”

Every fifteen years or so, the APA publishes a book called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which doctors around the world use as a guide for diagnosing mental disorders in their patients. Known as the DSM, it has been published seven times, first in 1952 and most recently in 2013. For each revision, a new task force of psychiatrists tweaks, refines, and often expands the descriptions, definitions, and symptoms of hundreds of psychiatric disorders. It’s not uncommon for definitions to be written more broadly, thus broadening the universe of people who might be diagnosed with a given disorder.

In the DSM-5, the 916-page version that came out last year, there was one important change made to the section on ADHD. The age at which a child can be diagnosed with ADHD was raised from seven to twelve. In the previous edition of the DSM, in order to meet the criteria for diagnosis, several symptoms of ADHD had to be present by age seven. Citing “substantial research published since 1994,” the authors increased the window for diagnosis by five years, meaning that twenty million more children are now eligible to be told they have ADHD.

And so if a child is deemed to meet the criteria for ADHD as defined in the DSM, even by a rushed pediatrician after a cursory twelve-minute examination, the clinical-practice guidelines strongly recommend medication as part of the first step in treating kids starting at age six. (Behavior therapy is recommended as a first step for four- and five-year-olds, followed by methylphenidate, or stimulants, if the behavior therapies “do not provide significant improvement and there is moderate-to-severe continuing disturbance in the child’s function.”)

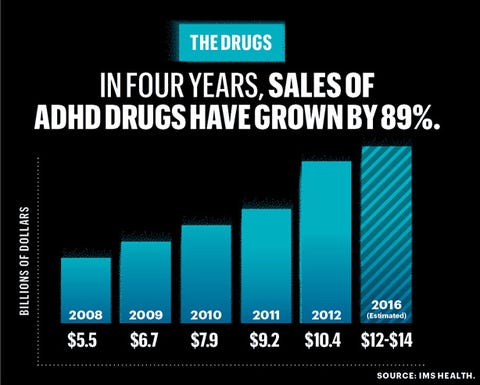

A cynical person might wonder whether the task forces who write the DSM are influenced by pharmaceutical companies, seeing that with each new disorder they add and each new symptom they deem valid, more people can get expensive prescriptions. ADHD drugs alone were a $10.4 billion business in 2012, a 13 percent increase over the year before.

“I think it happens in an indirect but nonetheless powerful way,” says Lisa Cosgrove, a clinical psychologist who is an associate professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston and a fellow at the Center for Ethics at Harvard. In a study of the DSM-5, she found that 69 percent of the task force acknowledged ties to the pharmaceutical industry. Many of these were likely indirect affiliations, but Cosgrove says that doesn’t matter. “It’s not that I think there’s this quid pro quo kind of corruption going on. But when the individuals who are charged with the responsibility of developing criteria or with changing the symptom criteria—I don’t think they are consciously aware of the way in which industry affiliations create pro-industry habits of thought.” Cosgrove points to what she calls a “major gap” in the APA’s disclosure policy for doctors who worked on the DSM-5: It allows unrestricted research grants from drug companies. “Now, ‘unrestricted’ means that the pharmaceutical company cannot in-house analyze the data…but there’s a wealth of social-psych research that shows that when you are paid even small amounts—and there’s the potential for future payment—it affects your behavior. If I get an unrestricted research grant from Pfizer for $500,000, and I’m hoping to get a $2 million grant, at some level I’m going to be aware of how I talk about the results.”

The journal Accountability in Research chose Cosgrove’s paper “Commentary: The Public Health Consequences of an Industry-Influenced Psychiatric Taxonomy” for publication in 2010, when a first draft of the DSM-5 was made public. In the paper, Cosgrove and her coauthors lambasted the psychiatric community for supporting a manual that largely ignores side effects and promotes diagnosis by constantly adding symptoms and disorders. “A psychiatric taxonomy [i.e., the DSM] which touts indication for medications, but is effectively silent about their associated risks, is evidently unbalanced and raises questions about undue influence,” they wrote. “The time has come to seriously reconsider whether the heavily pharmaceutically funded APA should continue to be entrusted with the revision of the DSM.”

Dr. Allen Frances, professor emeritus at Duke University School of Medicine, the former chairman of its psychiatry department, and the chairman of the DSM-IV (1994) task force, feels the problem is not corruption but the slow creep of misinformation. “I know the people. They’re not doing it for the drug companies—they really believe what they’re doing is right. They really believe ADHD is under-diagnosed, and they want to help people who should be getting medication. I just think they’re dead wrong.”

“It’s a disease called childhood.”

Frances points to the fact that in August 1997—the same year the CDC first started tallying ADHD cases in the United States—the Food and Drug Administration made it easier for pharmaceutical companies to advertise their drugs to consumers. Spending on direct-to-consumer drug advertising increased from $220 million in 1997 to more than $2.8 billion by 2002.

It’s not that Frances believes ADHD is not a real and valid diagnosis; he just believes that these days it’s made so frequently it has been rendered meaningless. “It’s been watered down so much in the way it’s applied that it now includes many kids who are just developmentally different or are immature,” he says. “It’s a disease called childhood.”

Falsely diagnosing a psychiatric disorder in a boy’s developing brain is a terrifying prospect. You don’t have to be a parent to understand that. And yet it apparently happens all the time. “Kids who don’t meet our criteria for our ADHD research studies have the diagnosis—and are being treated for it,” says Dr. Steven Cuffe, chairman of the psychiatry department at the University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville and vice-chair of the child and adolescent psychiatry steering committee for the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology.

The ADHD clinical-practice guidelines published by the American Academy of Pediatrics—the document doctors are supposed to follow when diagnosing a disorder—state only that doctors should determine whether a patient’s symptoms are in line with the definition of ADHD in the DSM. To do this accurately requires days or even weeks of work, including multiple interviews with the child and his parents and reports from teachers, plus significant observation. And yet a 2011 study by the American Academy of Pediatrics found that one third of pediatrician visits last less than ten minutes. (Visits for the specific purpose of a psychosocial evaluation are around twenty minutes.) “A proper, well-done assessment cannot be done in ten or fifteen minutes,” says Ruth Hughes, a psychologist who is the CEO of Children and Adults with ADHD (CHADD), an advocacy group.

Only one significant study has ever been done to try to determine how many kids have been misdiagnosed with ADHD, and it was done more than twenty years ago. It was led by Peter Jensen, now the vice-chair for psychiatry and psychology research at the Mayo Clinic, but at the time a researcher for the National Institute of Mental Health. After a study of 1,285 children, Jensen estimated that even way back then—before ADHD became a knee-jerk diagnosis in America, before one in seven boys had been given the diagnosis—between 20 and 25 percent were misdiagnosed. They had been told they had the disorder when in fact they did not.

Part of the problem is subjectivity, and the power of a culture that has settled on a drug-based solution. Decades of research have gone into trying to define the disorder in a clinical way, and yet the ultimate diagnosis—Your son has ADHD—is inherently subjective. And insurance companies don’t reimburse or reward doctors for time spent doing the diligent work involved in giving a proper opinion. “You have to observe the behavior of the child over different environments. You have to talk to the parents. You have to talk to the teachers. I don’t know an insurance company out there that pays for a pediatrician to call and talk to the teachers. They just don’t,” says Hughes.

Ned Hallowell does not accept insurance in his private psychiatry practice, which he says allows him to spend more time with patients. “But for the average person, it’s the luck of the draw,” he says. “Do they have a good, savvy pediatrician who can be careful about the diagnosis, or do they have somebody who just hears ‘ADD’ and writes a prescription?”

Lieberman, the APA president, says most doctors try to get it right. “Are there pressures that are packed on clinicians that make them less than optimally rigorous [in making a diagnosis]? Unfortunately, there are,” he says. “But I mean, you have our health-care financing system that’s quite dysfunctional, and it’s created a situation where doctors have to spend a certain amount of time with bureaucratic, administrative paperwork and regulatory-compliance stuff…. We also have a culture where there’s pressure, both from schools as well as from parents, to do something—to alleviate the problem and enhance the performance of the child. That’s no excuse, and doctors shouldn’t succumb to that. But, you know, doctors are human…. We’d like everybody to be these heroic figures who fulfill the virtues of the Hippocratic oath. I think most doctors aspire to try to do that. But human limitations being what they are…caveat emptor.”

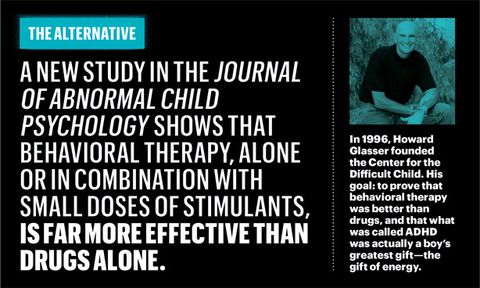

One man believes that drugging children’s brains is too risky. That until we get a lot closer to achieving a foolproof diagnosis for ADHD, we need to think twice about giving a single pill to a single child. He believes that what is called attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder might in fact be a boy’s greatest gift, the gift of energy. And that the best way to treat it is to first teach the boy to control the energy all by himself, because by learning to control it all by himself, a boy can channel that energy to help him succeed. That the responsible thing to do is first to see if there is some problem with the boy’s heart—not with the way it pumps blood, but with its ability to show and accept love. The man’s name is Howard Glasser, and he is one of those counter-cultural clinicians who, as American society has become inured to giving psychotropic drugs to kids, has built a practice predicated on opposing the very idea.

If he were a child today, Glasser would be given a prescription for a stimulant in about five minutes. Little Howie was a wired kid. Obstreperous. But good. A good kid. And when he grew up and became a family therapist—he has applied to earn his doctorate in education from Harvard starting this fall—he created a way of dealing with wired, obstreperous, uncontrollable kids who are, beneath all that, good. And he believes all of them are good.

He calls the method the Nurtured Heart Approach, and it seems simple on the surface: You nurture the child’s heart. If a child is hyperactive and defiant and has trouble listening and concentrating, Glasser feels it is our responsibility as a society—as grown-ups—to do everything we can for a child’s heart before we start adding chemicals to his brain, because what if his brain is fine? What if the diagnosis isn’t right? And even if it is, what if something else works?

Hyperactive, defiant—he was all those things. At home—the apartment his parents rented in Kew Gardens, a leafy, almost suburban corner of Queens—he was sometimes so defiant that his mother would shout into the air, asking what she had done to deserve this, her face brightening with incarnadine helplessness. His father was a salesman of electrical supplies, and he and Howie used to go at it pretty good. Sometimes, when it was his turn to teach Howie a lesson, his father would reach for the rubber machine belt. Howie took that punishment laughing. Heartbreaking laughter.

At school he would sit in the back of the class, cracking jokes until his teachers were overcome with that unique kind of exasperation that results from feeling outrage and disappointment at the same time. Outrage because you wouldn’t believe the mouth on this kid. Disappointment because he was so smart. Because he had so much potential.

Man, was Howie Glasser smart. That was the problem nobody saw: He was a funny, clever kid who scored high in both English and math without much studying. School bored him. The teachers, though, had to teach to every student in the class, and Howie felt forgotten. He didn’t need to listen, so he sat in the back of the room and goofed off, his gangly frame folded awkwardly into a too-small wooden chair. Kids would laugh, and he’d do it more. And every time the teachers got angry and pointed their fingers toward the principal’s office, struggling to keep from screaming at Howie—to keep from smacking him, probably—they were only feeding his recalcitrance. Finally, someone was paying attention to him! Deep down Howie didn’t like the negative attention, but it was better than no attention at all.

In junior high school, they wanted to hold him back. He couldn’t handle the next grade, they said—he couldn’t concentrate, he was hanging around with the wrong kids, he just wasn’t ready. But then Howie took a test, and his score surprised even the teachers who knew he was smarter than he let on. He scored high enough to skip ahead and graduated high school at sixteen.

Glasser graduated from City College with a degree in psychology, then got a master’s in counseling at New York University. He had started work on a Ph.D., also at NYU, but after a year or so he dropped out to do the thing he loved most, the thing that made all the noise go away, all the trouble, all the teachers who couldn’t figure out how to harness and channel his energy, his hollering parents who didn’t understand why he couldn’t be more like his older brother: He worked with wood.

Howie’s Woodworking opened on Third Avenue and East Twelfth Street in New York in 1980. He collected wood around the city—old floorboards from gutted townhouses, planks, pallets, scraps. He made planters and mosaics and odd pieces of furniture. People would see the sign and come in and ask if he could do bigger jobs—cabinetry, fine furniture, storefronts. Glasser would always tell them he could do it, even though he had no idea how. Then he’d hire people who could show him.

After a few years, Glasser moved out west, far from the overdrive of New York, to the Arizona desert. On his way out, in Boulder, Colorado, he got to know a man named Michael Davis, who, with his wife, Anita, was raising four sons, two of whom were adolescents at the time. The first time Glasser visited Davis’s house, there was some kind of minor drama unfolding that day, the kind of argument that periodically bubbles up in a house where teenagers live.

And the way the Davises handled it made Glasser weep.

“Michael and Anita were talking to their kids in the most loving way. I had never until that day—ever—encountered anybody who talked to their kids that way. I had tears streaming down my face,” he says. “In my world, in my circumscribed world, it was not the culture. It’s kind of breathtaking to me now.” Even as he tells this story almost thirty years later, Glasser has to pause, swallow hard, and clear his throat.

He eventually moved to Tucson with the woman who would be the mother of his only child, a daughter. Almost as soon as he arrived, he found a job at a family-therapy institute where he could use his psychology training. “It was like the sea parted,” he says. He felt as if he was doing what he needed to be doing. He got a second job at a clinic that was known for helping kids with behavior problems. Many of them had been diagnosed with ADHD.

“I had been one of these kids,” he says. “And here I am with twelve pre-adolescent kids who aren’t on their meds on the weekends—I would meet with them on Saturday mornings. So you get to see: These are very interesting human beings. I got to experience the truth of these kids off medication.”

Glasser would open up group discussions by asking what the rules should be. The children half-raised their hands and called out predictable answers: no hitting, no yelling, no bad words, no this, no that. The first time it happened, Glasser was seized with memories, a darkness moving over his brain like a shadow. “It was PTSD for me. I grew up with rules that start with no, and I hated rules that start with no. They always led to me getting in trouble, and ultimately getting hit,” he says. “It got my attention that kids saw rules that way.”

The clinic and the therapy institute both employed other bright young therapists, and they all called on their state-of-the-art psychology training to try to help the troubled families in their care. They used positive reinforcement. Instead of rules that started with no, they set rules like “Be respectful” and “Use nice words.” This was all fine and hewed closely to the education and therapy trends of the day. Kids behaved better. Families improved. But they didn’t change. Positive reinforcement is great, but there was only so far it could go with a difficult child. Glasser knew he hadn’t truly scraped away the artifice of defiant behavior to get at whatever pain was festering inside these kids. He wasn’t finding whatever it was that stirred them to yell and swear and make the grown-ups think they needed medication.

The problem with the positive rules was that there didn’t seem to be a very good way to teach them. The old rules were mostly taught when children broke them. If the rule is “No hitting” and one kid hits another, you’d teach the child the rule in that moment. “What you just did was wrong.” You’d tell him to go sit in the corner, or go to his room, or apologize. But in those moments, everyone’s upset. The kid who got hit is crying, the hitter is angry and scared, and the grown-up is amping up the authority. The offending child gets all the attention. The rule doesn’t stick.

“They don’t need us to figure out a video game for them. They figure it out in three minutes, and then they become stars.”

Still, Glasser saw that kids seemed to like “no” rules because they’re clear. The line of transgression was definite. He had an idea: What if he told the children how great they were when they didn’t break a rule? It would be like a video game. When you do something great while playing a video game—when you simply do what the game expects—you get points and you get to keep going. When you go out of bounds or break one of the game’s rules, no one yells at you or reminds you what rule you’ve broken. You simply miss a turn or lose points. And there is no grudge once you pay the fine. As Glasser wrote in his first book in 1999, Transforming the Difficult Child, “When the consequence is over, it’s right back to scoring.”

Kids love video games. “They don’t need us to figure out a video game for them,” he says. “They figure it out in three minutes, and then they become stars. The beauty of those games is the energy of success is so strong, consistent, reliable, available. If they break a rule in the next two seconds, the game unplugs momentarily. Grown-ups look at the consequences in these games and we don’t always see the truth of what’s going on. It looks to us like, Oh my God, huge consequence—blood spurting, heads rolling. But actually, the kid’s out of the game for two seconds but it feels like an eternity to them because they’ve become such a devotee of being plugged in to success, and they vividly feel the energy of missing out. When the consequence is over, they don’t just come back into the game, they come back ever more determined: I’m not gonna break another rule.”

And so he thought, What if a child was sitting quietly, not bothering anyone, and you went out of your way to congratulate him on that, very specifically, by telling him how proud you are that he’s not hitting anyone, not screaming, not throwing toys, but just sitting quietly? What if you gave a child the equivalent of points—what if you thanked him or hugged him—for not putting his feet on the couch? How would he respond to that?

He’ll like it, it turns out.

“I started accusing kids of being successful for not breaking rules. Nobody ever in my professional career had done that,” he says. “All of a sudden—and it was as weird as it could be—I knew I was speaking to some level of a kid’s soul. I knew it was nourishing them in some way. It was like me weeping at Michael Davis’s house. In my professional career, no kid had ever been told they were successful when it came to rules.”

Many of the people I interviewed who have had direct experience with ADHD—parents of children who’d been diagnosed, psychiatrists, adult ADHD patients—assured me, within the first minute of our conversation, that ADHD is a real disorder, not some made-up condition.

“It’s important to understand that ADHD is a very real, serious, neurobiological disorder,” said Saltarelli, the neurologist who was formerly senior vice-president of clinical development at Shire, maker of Adderall and Vyvanse, which is now the most common brand of stimulant prescribed for ADHD. He repeated this point several times during our hour-long conversation.

“I don’t think in the medical community or in the research community there is any question that this is a brain disorder. I really don’t think that is in question,” Ruth Hughes, the CHADD CEO, told me after I asked her about the validity of brain scans that purport to show ADHD, which have been disputed by other scientists.

“There is no doubt in my mind that I really believe this is a disorder, disease, condition, whatever you do—like, it is for real,” said Tracie Giles, a parent of four children, two of whom have been diagnosed. She is the coordinator of the local CHADD chapter in Wayne County, Michigan.

The Epidemic

2003: The No Child Left Behind Act rewards schools for higher test scores. Kids with ADHD get more time to take tests, and sometimes their scores aren’t counted in the overall average. As the law rolls out, ADHD diagnoses increased 53% in poor areas.

The interesting thing is I never asked any of these people whether ADHD is real. But their defensiveness is understandable. ADHD isn’t strep throat—there’s no culture, no test. To find out if you have it, or if your son has it, or if your daughter has it, you just need a human being to say so—a physician or a psychiatrist—and that makes some people skeptical. Google “Does ADHD exist?” Up pop the detractors who call the very disorder into question.

ADHD has become the most controversial medical topic in America when it comes to children. In 2000, Bob Schaffer, then a Colorado congressman, called a hearing about ADHD medication before the House Committee on Education and the Workforce. “I had been in politics a long time even before I had this hearing,” he says. “And you would think that with issues of national missile defense, the space program, the billions we spend on public education, the China trade bill I voted on—that something else would have resulted in more blowback, but I can’t think of anything else that did. It inspired more personal hostility and defensiveness than anything else I’d ever been involved in.”

The biggest reason: Managing ADHD, for most people who receive the diagnosis, includes taking medication. If the diagnosis is real, a prescription can turn around a child’s life in an instant, improving his ability to concentrate and jacking up his self-esteem. Denying a child who needs the medicine is as cruel as forcing it on a kid who doesn’t. Even Howard Glasser is not anti-medication—not entirely. He believes that in rare cases it can be effective as a temporary measure. But it’s a terrifying choice to make for many parents.

Ned Hallowell once famously said that stimulants were “safer than aspirin,” a statement he has since backed off of. (“That’s almost a preposterous statement for anyone to say,” says Saltarelli.) “I think that was misleading,” Hallowell says now. “I was dealing with people who thought these medications were extremely dangerous, and if they’re used properly, they are not. But now I don’t say that anymore because I’m worried about high school students taking them without any medical evaluation.” But Hallowell stands by his assertion—widely corroborated—that it’s silly to try to treat ADHD without medicine. “I certainly am not gonna try to persuade you to use medication, but once you learn the facts, chances are you will want to. Because doing a year, say, of non-medication is sort of like saying, Why don’t we do a year of squinting before we try eyeglasses.”

In 1999 the National Institute of Mental Health published its landmark study “Multimodal Treatment of ADHD,” which was led by Peter Jensen; 579 children ages seven to nine took part. The study declared that the best treatment, across the board, is medication combined with behavioral therapy—but that the combination works only marginally better than medication on its own, with no behavioral component. This made a lot of parents feel better about accepting a prescription for their children, and the study is frequently cited by pharmaceutical companies, psychiatrists, and organizations like CHADD.

“Medication alone is not the solution to the long term.”

Research published since the multimodal study, however, suggests that treating kids who have ADHD with cognitive behavioral therapy can have the same positive effect as stimulants. A new study in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology shows that behavioral therapy, alone or in combination with stimulants, is far more effective than medication alone. The children in the study—forty-four boys, four girls, all diagnosed with ADHD—were given varying doses of medication and behavioral therapy, and researchers monitored their episodes of “noncompliance” each day. The worst-behaved children were the ones receiving only drugs and no behavioral therapy. Even kids given a placebo while also receiving some behavioral therapy behaved far better than kids being treated with drugs alone. The sweet spot was a low dose of medication plus behavioral therapy.

William Pelham of Florida International University, the lead author of the study and one of the original investigators on the multimodal study, says that these findings show that psychosocial treatments “are the key to long-term success. Medication alone is not the solution to the long term.”

I wanted to talk to an actual person at a drug company about the difficult choice. I called Novartis, which manufactures Ritalin and Focalin XR. A media-relations specialist, Julie Masow, declined to make anyone from the company available to me for an interview, citing the fact that it was summer and people were traveling, and instead provided me with a vague written statement. But eventually Masow agreed to provide written answers to any questions I wished to send her via e-mail. It was a fairly fruitless exercise—a lot of anodyne corporate-speak about how “ultimately, the decision to prescribe an ADHD treatment for a child with ADHD is between the physician and the patient’s parent/guardian” and “Patients and parents/guardians also receive a copy of the medication guide included in the drug package insert.”

Novartis is right, to a point—pharmaceutical companies do not prescribe the drugs they manufacture. So do they care what happens once the drugs leave the factory? When I asked Saltarelli of Shire whether drug companies should do anything to make sure their products are used correctly, he said, “It is our responsibility to make sure that the drugs are being appropriately utilized. It’s obviously impossible for us to be in any way involved in diagnosis, let alone in every doctor’s office where diagnoses are being made. But we do feel an ethical obligation—and we’ve actually invested quite a bit to do whatever we possibly can through educational efforts to make sure that these drugs are being used appropriately.” When I asked the same question of Novartis, the answer (via e-mail) was “Novartis supports only the appropriate use of ADHD medicines as indicated and prescribed by qualified, licensed health-care providers. Novartis does not participate in the diagnosis of patients with ADHD, as the diagnostic criteria…”

Karen Lowry, a nurse in Medford, New Jersey, helps run a local CHADD chapter. She has four children, the youngest of whom has ADHD. “When he was first diagnosed, we were adamantly against medication. No, it might prevent his brain growth. We’ll deal with behavioral programs. It’s not happening,” she says. “But as first grade progressed and we saw our child with an ADHD diagnosis experiencing hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness in a classroom setting with a teacher who was really not very understanding, we saw a kid who was falling through the cracks. We saw a kid who was not developing friendships, peers who were always blaming him for everything that was going on around him. So my husband and I looked at each other again and said, Oh my gosh, we need to rethink this. Are we not being fair to him? What’s worse? Not fully understanding the medication and what can happen in a positive way, or just standing our ground saying, We’re unsure about this?”

Lowry and her husband ended up putting their youngest son on a stimulant. His behavior improved vastly, and the ADHD seemed to be under control. But toward the end of the school year, he developed severe facial tics, a side effect of some ADHD medications. They took him off the medication for the summer, a decision many parents make at some point. “He’s adjusted pretty much,” she says. “He’s on a very low dose because he does get the headaches. It’s sometimes hard to balance, you know, the side effect with the effects of the drug.” Overall, Lowry thinks they made the right call. It’s a question she gets a lot from other parents of children with ADHD. “I would never tell anyone to put their kid on medication. All I will say is look at the results. And I always commend the parents who come to our classes, even if they’re frantic: Your kid will be okay because you’re here.”

Ruth Hughes, CHADD’s CEO, finds herself defending—or justifying—ADHD as a diagnosis regularly. More than twelve thousand people are members of the organization. Its annual budget is about $3.5 million, of which up to 30 percent can come from the pharmaceutical companies that manufacture ADHD drugs, according to Hughes.

During our phone interview, I asked Hughes whether CHADD could be classified as pro-medication. “Well, I’m going to reframe this a little bit,” she said. “We are pro-science, pro-research. Our issue is to make parents or adults who potentially have ADHD to be very well informed consumers of medical services.”

I told her I was asking because while there are lots of books and articles out there about how to treat ADHD without medication, you hardly ever see anything about that on CHADD’s Web site or in its bimonthly magazine, Attention.

“You don’t,” she said.

If we don’t know what we’re doing, maybe we shouldn’t be doing it. Putting a child on highly addictive psychotropic drugs ought to be very difficult, not shockingly easy. And yet even if Peter Jensen’s twenty-year-old estimates about misdiagnosis are still correct, an astonishing 25 percent of today’s 6.4 million kids, overwhelmingly boys with developing brains, might be experiencing side effects for no reason. Because he made that assumption long before ADHD became such a popular diagnosis, the number could be far higher now.

Yes, the drugs these children consume may work. They help them focus for longer periods of time. They help them do better in school. But consider this: Stimulants work on just about anyone. “These are powerful drugs,” says Bob Schaffer, the former Colorado congressman. “They would work on me. They would make anyone more focused. And everyone’s happy because the kid is now under control.” The fact that the drugs would help you perform better at work doesn’t mean you should take them. And it certainly doesn’t mean a seven-year-old boy who doesn’t suffer from a psychiatric disorder should be taking them.

Why not, if they help him do better? Because, for one thing, an important study of four thousand children published last year concluded that children who took stimulants didn’t do any better in school than kids who didn’t. But also, and perhaps more important, because he might not be the same seven-year-old boy once he starts, and he may never be the same boy again.

Another little-examined feature of these drugs is the global changes in personality that they can cause. Jim Forgan is a psychologist in Jupiter, Florida. The first thing you see on his Web site is an ad:

“Dr. Jim Forgan’s Parent Support System. 10 Easy to Use Modules. Over 80 Educational Videos. Downloadable Resources. Online Access 24/7. And Much More!”

The video support system is available for a one-time fee of $49.97. Forgan is the coauthor of a book called Raising Boys with ADHD, also available for purchase. He speaks from experience. His son has been diagnosed with ADHD. Forgan knows all the warning signs, and he tells parents about them. He’s in favor of drugs when they’re administered correctly—starting with low doses, watching vigilantly for side effects, stopping use if the side effects outweigh the benefits.

How do you know if the side effects outweigh the benefits?

“Careful monitoring,” says Forgan. “And for me personally, with my son being on the stimulant medications, those are medications you don’t have to take every day, so we would give him the holiday breaks on the weekends and spring break and summertime, just so that he didn’t have the medication all the time. And yeah, there’s a difference, he has more energy. My son doesn’t like to take the medications because he feels like it makes him feel flat, and he doesn’t like what it does to his personality. And he says he’s not the same fun person that he is when he’s not on the medication. And some of that fun gets him in trouble at school, because he’s funny and knows how to entertain people. But at the same time, he likes that characteristic about himself—that he is fun and knows how to get people laughing and working together and bring energy into a room. Kinda like the life of the party.”

I tell Forgan that there is something heartbreaking about the fact that such a lively part of his son’s personality disappears when he’s on medication, and that his son knows it disappears. “Is it just that he was getting into too much trouble?” I ask.

Forgan pauses and says, “Right. Yup, it gets him in trouble and he hasn’t—when he was in elementary school, he didn’t have his own ability to have the self-control not to say impulsive things and do impulsive things that other people find funny but the teacher finds very annoying.”

“And you see the fun part of him reemerge during breaks from the medicine?”

“Right.”

Howard Glasser’s biggest fear in life is that a child might grow up not knowing how great a person he is. It keeps Glasser awake at night sometimes, this image of a kid thinking he’s no good. It lodges a pit in his throat.

Ned Hallowell, the ADHD expert who has the disorder, writes books about it, has talked about it on Dr. Oz, and thinks medication usually gets good results, feels the same. “The medical model is so slanted toward deficits that it excludes strengths—and it also reinforces stigma, that this is shameful, this is bad, this means you’re a loser. And that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s the old line of whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right. And what breaks my heart is how these kids, and the parents along with them, get broken in school, and they come out of twelfth grade believing that they’re stupid. Believing that they’re defective. But this trait, these are the people who colonized this country! Just think of it: Who in the world would get on a boat in 1600 and come over here? You had to be some kind of a nut. You had to be a visionary, a dreamer, an entrepreneur—you know, a risk-taker. That’s our gene pool. So this country is absolutely full of ADD.”

So there is something great about having ADHD. The question is how to treat the difficult parts in a way that pushes the greatness forward.

“I confront kids with their own greatness,” Glasser says. “Because that’s what I think allows a kid to go from an ordinary life to a purposeful life. To see who they really are. The worst-case scenario in life is that a boy grows up thinking: Who I really am is a kid who annoys everybody.”

In 1994 Glasser opened the Center for the Difficult Child in Tucson, his first effort to teach therapists his Nurtured Heart Approach. In 1999 he published Transforming the Difficult Child, which has quietly sold nearly 250,000 copies. Today he runs an organization he named the Children’s Success Foundation, which is an expanded effort to teach educators and therapists around the United States how to use what he has found from twenty years of practicing the Nurtured Heart Approach.

“It’s much more about reaction than attention.” That sentence appears on page 10 of Transforming the Difficult Child. It’s a profound distinction, and there is no deeper nor more simple understanding of a child’s needs. Parents of intense boys can shower their children with love and attention, and still the boys might be difficult boys. What’s important is how you react to what a child does, good or bad, Glasser says. Mostly, we get animated when our kids do something bad. We get worked up, and we give them energy—negative energy, but energy nonetheless. But when a difficult child is sitting quietly, playing or writing or drawing, not disturbing anyone, not throwing food, not picking on a sibling—we do nothing. We don’t acknowledge it at all. The way a difficult child gets a parent’s energy, then, is to do something bad.

“Most parenting approaches have you giving a strong punitive consequence that’s all energy and that confirms that, as a parent, you’re highly available through negativity—you’re a toy that works when they push buttons,” he says. “And you work if and only if they act out bigger.”

Watching Glasser work with a child is a marvel.

“Maybe you don’t quite know what calm means. Let me tell you how great calm is.”

He is sitting on the carpeted floor of a family’s basement playroom, his lanky frame contorted into what passes for comfort for a sixty-three-year-old man sitting on the floor. He is watching a sandy-haired boy of seven play with his toys. A few minutes before, the boy had been hitting his younger brother, and he had been scolded, hit his brother again, and been banished from the kitchen. Now he plays peacefully.

“I see that you are very calmly building with your Legos,” Glasser says to the boy, in a smooth and even voice, as if he were commenting on clouds moving across the sky. “That’s really great to see. It shows that you respect your mom and dad, because they love it when you play nicely.”

The boy just nods without looking up, like, Sure, thanks mister. So Glasser keeps at it.

“So I assume you heard what I said. And I just want to elaborate a little more. Because here’s what’s great: You have this wonderful quiet way of thinking things through. I can tell that you’re thinking about what it means to be calm. And maybe you don’t quite know what calm means. Let me tell you how great calm is. What does it take to be calm?”

The boy looks up now. Words are starting to register with him. His face is blank, but he’s thinking. This is unusual for him—getting attention, getting a reaction, for being so good.

“Well, while you’re thinking about it, let me tell you. It takes wisdom, for one thing, because you could be yelling. You could be annoying people. Have you ever been annoying? Well, you’re not being annoying. You’re not running around the lunch table. You’re not throwing your food or hitting your brother. All these things that kids your age could do, you’re not doing. That’s being calm. That shows me you’re being thoughtful. That you care about other people, and that you’re in control of your body. Being in control takes a lot of concentration and effort. Doesn’t it?”

The boy nods, just barely. He is looking right into Glasser’s eyes. For years, since he was two, the boy has had trouble controlling his body sometimes. Sometimes the energy inside him is just too much, and it builds like gas trapped in rock until it bursts forth in a violent, painful mess. At times he has driven his parents to a crisis of helplessness. The heartbreaking part is the boy has tried so hard to control his energy, and he’s gotten better at it. But sometimes he still just can’t. Once, in the middle of the night, when he was four, he wouldn’t go to sleep and kept throwing toys at the door until his mother cried and his father yelled, and then through the tears streaming down his tiny cheeks he looked up at his father over the plastic gate that was jammed in his bedroom door and, in a moment of astonishing self-awareness, pleaded, “I need to calm my body down!” When he started school, his parents mentioned to the school psychologist that their son sometimes had an issue with impulsive behavior. The psychologist, who had never met him—who had never met the boy—told the parents that it sounded like he probably had ADHD. The parents had had their son evaluated by child psychologists, pediatricians, teachers, and independent therapists, and not one person had ever suggested ADHD, and in fact, the boy’s pediatrician and the rest of the school’s counseling, teaching, and professional staff said resolutely the boy showed no signs of it. (When he heard that a school psychologist had said this, Glasser wasn’t surprised. “Sure. Your son is intense. If you wanted to go out and get him a prescription for ADHD medication, you could do it tomorrow,” he told the parents.)

“That’s right,” Glasser says to the boy. “It does take a lot of effort. And I want to tell you something: A few minutes ago, you hit your brother. And he started crying, and then you got really upset when your parents told you to stop. You were really mad at him and at them. But look at you now. Look at yourself! You calmed yourself down so beautifully. And that was an amazing, amazing thing to do, because it’s hard to calm yourself down when you’re so upset. But you figured out how to control your body in a really bad moment. You did that yourself. No one did it for you. And that shows greatness. That shows me and everybody else that you have greatness inside you.”

The boy is looking at him still, locked in.

And, slowly at first, the boy begins to smile. And then the smile spreads across his whole, beautiful seven-year-old face. His teeth, missing here and there and sticking out in gaps where he used to suck his thumb, shine across the room, and he lets out a giggle, and the giggle turns into the kind of proud, embarrassed laugh kids do when they haven’t learned how to take a compliment. His face is lit up—he is shocked by what he has just heard, and shocked by his own joyful reaction. He’s laughing, looking at this man who has just told him that he has greatness within his soul, and the kid slaps the floor, then crosses his skinny arms on top of his head, and smiles with pride. He is euphoric.

It is almost as if he has been drugged.