The New York Times

Water Supplies From Glaciers May Peak Sooner Than Anticipated

Raymond Zhong – February 7, 2022

The world’s glaciers may contain less water than previously believed, a new study has found, suggesting that freshwater supplies could peak sooner than anticipated for millions of people worldwide who depend on glacial melt for drinking water, crop irrigation and everyday use.

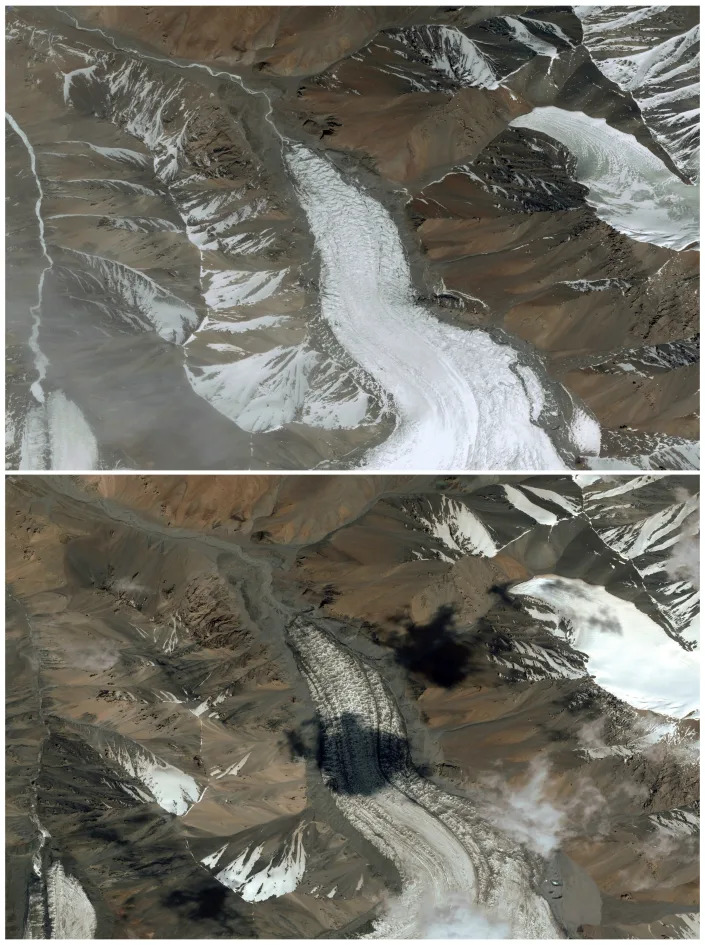

The latest findings are based on satellite images taken during 2017 and 2018. They are a snapshot in time; scientists will need to do more work to connect them with long-term trends. But they imply that further global warming could cause today’s ice to vanish in many places at a pace faster than previously thought.

In the tropical Andes, for instance, the study estimated glacier volume to be 27% less than the scientific consensus as of a few years ago. In parts of Russia and northern Asia, glacier volume was 35% smaller, the study found.-

Worldwide, the study found 11% less ice in the glaciers than had been estimated earlier. In the high mountains of Asia, however, it found 37% more ice, and in Patagonia and the central Andes, 10% more.

The new estimates come from a more detailed and realistic digital reconstruction of Earth’s 215,000 glaciers than had been possible before, said Romain Millan, a geophysicist at the Institute of Environmental Geosciences in Grenoble, France, and lead author of the study, which was published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Even so, “we still have lots of uncertainty in some regions,” Millan said, mostly because of the scarcity of on-the-ground measurements, which help to inform any digital reconstruction. Those regions, including the Andes and the Himalayas, “are the ones where people rely on fresh water coming from glaciers,” he said.

The melting of glaciers is threatening livelihoods and reshaping landscapes in North America, Europe, New Zealand and many places in between.

In the upper Indus basin of the Himalayas, which straddles Afghanistan, China, India and Pakistan, glacial melt accounts for nearly half of river flow. Yet logistical and political challenges mean scientists can monitor only a small share of the Himalayan glaciers, said Anjal Prakash, a water expert at the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad who did not work on the new study.

“It’s a data-deficient region,” Prakash said. “Countries do not cooperate. They don’t share information with each other.”

With 1.5 billion people benefiting from the water and other resources of the Himalayas, while also facing growing risks of severe floods, the region “is just waiting for a disaster to happen,” Prakash said.

As glaciers have melted, they have contributed to rising global sea levels. The new study suggests that, all together, they could add 10 inches to the oceans instead of the foot or so that was estimated earlier. Either way, it is small compared with what the melting of Greenland and Antarctica could add to sea levels in the far future if the planet heats to catastrophic levels.

To produce their new estimates of glacier dimensions, Millan and his colleagues combined more than 811,000 satellite images to clock the speeds at which the glaciers’ surfaces are moving. Glaciers may look like solid, unchanging masses, but in fact, they are constantly in motion: sliding across the terrain; deforming under their own weight; flowing, syrup-like, down valleys. This movement is a clue to the amount of ice that is locked inside.

“The thickness of the glacier controls how fast it moves,” said Daniel Farinotti, a glaciologist at the Swiss university ETH Zurich who did not work on the new study. “And so, vice versa, if you know how fast it moves, you can say something about the thickness.”

The high resolution of the satellite images allowed Millan and his colleagues to capture fine variations in the glaciers’ thickness, such as narrow troughs in the ground underneath. They could map small ice caps in South America, Europe and New Zealand that had never been mapped before.

In certain ways, scientists understand less about some of the glaciers draped over the world’s mountains than they do about the much larger ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica, said Mathieu Morlighem, an earth scientist at Dartmouth College who worked on the new study.

Only a few thousand glaciers worldwide have been measured on-site. In places like North America, the balmier climate means more pockets of water in the glaciers, which can thwart radar measurements. Compared with the giant ice sheets, where fast-moving ice has smoothed the underlying bedrock over time, the terrain beneath mountain glaciers can be “just so complex,” Morlighem said, making it harder to gauge their dimensions.

“Just 10, 15 years ago, we barely knew the area of the glaciers,” said Regine Hock, a geoscientist at the University of Oslo in Norway who was not involved in the new research. Estimates of glacier volume were “very, very rough,” she said.

Today’s “data revolution” is helping scientists make better predictions about local and regional water resources, even if the big picture globally — that the glaciers will thin substantially during this century — is unlikely to change much, Hock said. “There is only so much ice,” she said, “and then it’s gone.”