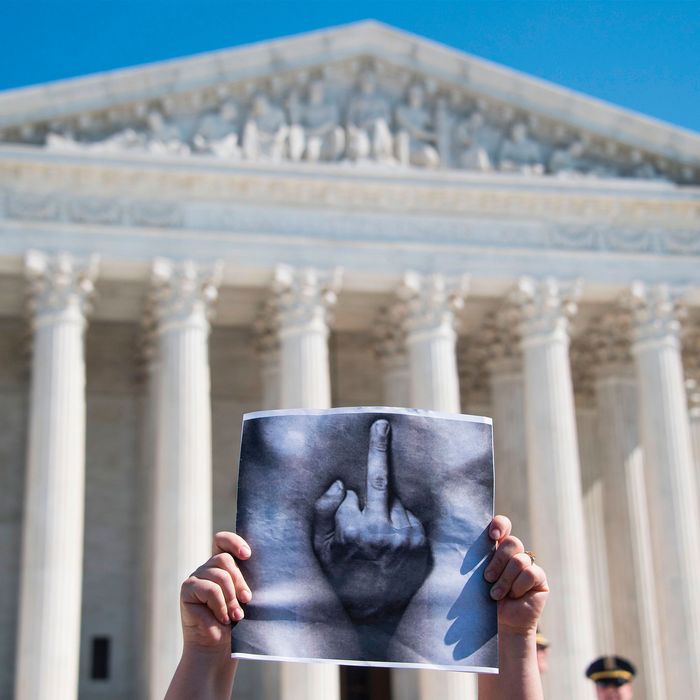

The Ruling Minority Will Stop at Nothing to Stay in Control

By Rebecca Traister October 29, 2018

Diagnosing the mood of the citizenry is a notoriously dicey proposition, as is making electoral predictions based on it. Even trusting empirical research, the polls, has been shown to be a fool’s errand. I’ve now been on the road for close to a month promoting my book, traveling from D.C. to Minneapolis to Portland, Oregon. I’ve talked to self-selected crowds of hundreds of mostly (but not all) progressive women, many (but not all) white. And for every person who tells me that my book — about the transformational power of American women’s political anger — has come out at the “perfect” (i.e., the absolute fucking worst) time, when fury over Brett Kavanaugh has gripped the nation, I’ve encountered another who’s made me doubt its very premise. “How can I feel driven again?” I’m asked. “How can I get my friends back out on the sidewalks when they feel like winning isn’t possible, when they’ve decided they might as well pack it in?”

Women, as well as men, tell me they’ve turned off the news, taken a break from protest or campaigning to refocus on their families or themselves; they feel anxious, suddenly aware of the possibility that the blue wave of Democrats may not materialize, that the efforts to stave it off via gerrymandering and voter suppression and the gush of Koch money into tough races may win out. In other words, Kavanaugh’s ascendance hasn’t jolted these people to redouble their efforts to topple Republicans at the polls in November. Rather, it’s left them deeply demoralized, drained of hope and energy at perhaps the most crucial moment of all.

In some regards, these bracing realizations are overdue. Yes, Democrats might well lose the midterms. But that this is sinking in only now, as an aftereffect of Kavanaugh’s confirmation, is the devil’s timing — if, that is, the ultimate impact is to paralyze Democrats. That’s the purpose of the Republicans’ victory lap, of course. By cheerily casting protesters as a mob that incited a backlash in popular opinion (a backlash only debatably borne out by polling), they’re hoping that the loosely aligned left resistance eats its own tail in response. This summer, some Democrats worried that if Kavanaugh’s confirmation were blocked, the party’s voters would be placated and stay home in November while the right would rev up into a frothing electoral force. But somehow, the right’s win has been successfully framed by the president and Republicans as something that needs to be avenged.

Lots of American women, especially white middle-class women, are new to intense progressive engagement; their energies are necessary and may be game changing. But they’re also perhaps most likely to be shocked by the revelation of the limits of their power. Aditi Juneja, the lawyer, activist, and co-creator of the Resistance Manual, told me while I was reporting my book that she’d noticed over her years organizing that white women tended to have “faith that if they voice their opinions to their representatives, that they will be heard, that they will have influence.” To Juneja, this stood in stark contrast to assumptions made by activists of color, who often expressed “no faith that politicians will see that there is any cost to disappointing black and brown people.”

To some extent, the past two years have given newly minted activists reason to feel confident: The pressure applied at town halls and via calls and letters to senators (including to Maine’s Susan Collins) was enough to stave off repeal of the Affordable Care Act in 2017. When #MeToo, first initiated by Tarana Burke more than a decade ago to address sexual assault in communities of color, took a new form in 2017, after mostly white women in highly paid industries spoke up for the first time, many of the men they accused wound up suffering heretofore rare consequences such as the loss of jobs and power. A series of teachers’ strikes in 2018 led to higher wages even in states where the striking itself was illegal. There has been an influx of first-time female candidates, many black and Latina; on the Democratic side, those women have emerged victorious in primary after primary. The furor over the Trump administration’s family-separation policy this summer was not enough to reunite the hundreds of children forcibly taken from their parents, some of whom were deported, but the civil disobedience was enough to stop new separations.

Yes, it’s human to respond to a crushing loss by retreating, by taking time to recover before getting back up again. When we think about the left-leaning activism that has bloomed since Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton — the sidewalk-pounding registration efforts, the new candidacies, the organizing and protesting, the building of a progressive infrastructure outside the Democratic Party — we don’t often linger on the two and a half months between Election Day and the Women’s March.

Those were days of fear and grief, not to mention intraparty excoriation. Identity politics, feminism, the apathy of the young, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, everybody and everything were blamed for the cataclysmic result. It wasn’t until the Women’s March — ultimately organized and led by a multiracial coalition that insisted on linking left-progressive principles and causes — became the biggest single-day political demonstration in the country’s history that we began to see an energetic movement taking shape.

We don’t have that kind of time right now. We don’t have months, or weeks, or even another second to spend recuperating. We have eight days.

But it’s hard! Being schooled on your own powerlessness by a minority takes the breath out of you. They have the power. That is the point. If it were so easily won away from them, we wouldn’t be in this political situation, which is not new but stretches back centuries and will extend far beyond the end of our lives. It may be devastating to those who thought they had leverage within the white patriarchy to experience what it’s like for people who’ve never had that illusion, who’ve never believed that speaking up or writing to senators or even voting would improve their lot. But the Kavanaugh steamroll can also be instructive and reorienting.

This is where hope becomes a tactical necessity. And out on the road, I have encountered a few gusts of it. In Boston, one woman in her mid-20s told me that her friends who’d remained politically disengaged finally had been radicalized by Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony; they’d seen the misogyny and Republicans’ willingness to support it and were suddenly — just now, in the fall of 2018 — determined to try to prevent the party’s further rise. In St. Louis, Democratic state representative Stacey Newman told me that when she made a call for 30 people to show up to a phone bank, 165 volunteered.

If past generations, kept from polls and beaten on picket lines, tear-gassed and hanged and enslaved and incarcerated, hadn’t kept imagining that their efforts would one day bear fruit, even if it would be after their deaths, we’d be in more trouble in 2018 than we already are.

There will be time — our lifetimes — to temporarily pull back and recover from bitter defeats; there will be so many more bitter defeats. But any impulse toward flirting with despair must be resisted. The left has a weapon on the table for a little over a week. It is a compromised weapon, rendered duller by the forces it has the potential to challenge. But the desire to give up, if only for a while, will ensure its uselessness. Now is the season for progressives, the newly motivated and the old stalwarts, to get out of their own front doors and start knocking on others, to drive people to polls, to call local campaigns and ask how they can help those who never had the luxury of being able to catch their breath or turn away in the first place.

*This article appears in the October 29, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!