Associated Press

A Wagner ex-convict returned from war and a Russian village lived in fear. Then he killed again

Dasha Litvinovau – June 27, 2023

TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — When Ivan Rossomakhin returned home from the war in Ukraine three months ago, his neighbors in the village east of Moscow were terrified.

Three years ago, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to a long prison term but was freed after volunteering to fight with the Wagner private military contractor.

Back in Novy Burets, Rossomakhin drunkenly wandered the streets of the hamlet 800 kilometers (about 500 miles) east of Moscow, carrying a pitchfork and threatening to kill everyone, residents said.

Despite police promises to keep an eye on the 28-year-old former inmate, he was arrested in a nearby town on charges of stabbing to death an elderly woman from whom he once rented a room. He reportedly confessed to committing the crime, less than 10 days after his return.

Rossomakhin’s case is not isolated. The Associated Press found at least seven other instances in recent months in which Wagner-recruited convicts were identified as being involved in violent crimes, either by Russian media reports or in interviews with relatives of victims in locations from Kaliningrad in the west to Siberia in the east.

Russia has gone to extraordinary lengths to replenish its troops in Ukraine, including deploying Wagner’s mercenaries there. That has had far-reaching consequences, as was evident this weekend when the group’s leader sent his private army to march on Moscow in a short-lived rebellion. Another has been the use of convicts in battle.

The British Defense Ministry warned of the fallout in March, saying “the sudden influx of often violent offenders with recent and often traumatic combat experience will likely present a significant challenge for Russia’s wartime society” as their service ends.

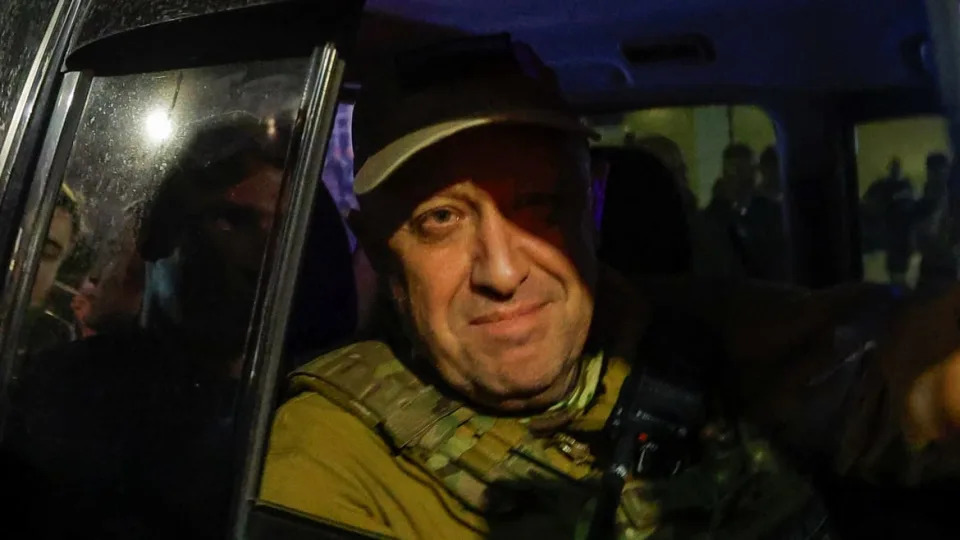

Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin said he had recruited 50,000 convicts for Ukraine, an estimate also made by Olga Romanova, director of the prisoner rights group Russia Behind Bars. Western military officials say convicts formed the bulk of Wagner’s force there.

About 32,000 have returned from Ukraine, Prigozhin said last week, before his abortive rebellion against the Defense Ministry. Romanova estimated it to be about 15,000 as of early June.

Those prisoners agreeing to join Wagner were promised freedom after their service, and President Vladimir Putin recently confirmed that he was “signing pardon decrees” for convicts fighting in Ukraine. Those decrees have not been made public.

Putin recently said recidivism rates among those freed from prison through serving in Ukraine are much lower than those on average in Russia. But rights advocates say fears about those rates rising as more convicts return from war are not necessarily unfounded.

“People form a complete absence of a link between crime and punishment, an act and its consequences,” Romanova said. “And not just convicts see it. Free people see it, too -– that you can do something terrible, sign up for the war and come out as a hero.”

Rossomakhin wasn’t seen as valorous when he returned from fighting in Ukraine but rather as an “extremely restless, problematic person,” police said at a meeting with fearful Novy Burets residents that was filmed by a local broadcaster before 85-year-old Yulia Buyskikh was slain. At one point, he even was arrested for breaking into a car and held for five days before police released him March 27.

Two days later, Buyskikh was killed.

“She knew him and opened the door, when he came to kill her,” her granddaughter, Anna Pekareva, wrote on Facebook. “Every family in Russia must be afraid of such visitors.”

Other incidents included the robbery of a shop in which a man held a saleswoman at knifepoint; a car theft by three former convicts in which the owner of the vehicle was beaten and forced to sign it over to them; the sexual assault of two schoolgirls; and two other killings besides the one in Novy Burets.

In Kaliningrad, a man was arrested in the sexual assault of an 8-year-old girl after taking her from her mother, according to a local media report and one of the girl’s relatives.

The man had approached the mother and bragged about his prison time and his Wagner service in Ukraine, according to the relative, who spoke to AP on condition of anonymity out of safety concerns. The relative asked: “How many more of them will return soon?”

In its recruiting, Wagner usually offered convicts six-month contracts, according to media reports and rights groups. Then they can return home, unlike regular soldiers, who can’t terminate their contracts and leave service as long as Putin’s mobilization decree remains in effect. It wasn’t immediately clear, however, whether these terms will be honored after Prigozhin’s unsuccessful mutiny.

Prigozhin, himself a former convict, recently acknowledged that some repeat offenders were Wagner fighters -– including Rossomakhin in Novy Burets and a man arrested in Novosibirsk for sexually assaulting two girls.

Putin recently said the recidivism rate “is 10 times lower” among the convicts that went to Ukraine than for those in general. ”The negative consequences are minimal,” he added.

There isn’t enough data yet to assess the consequences, according to a Russian criminology expert who spoke on condition of anonymity out of safety concerns.

Incidents this year “fit the pattern of recidivist behavior,” and there’s a chance that those convicts would have committed crimes again upon release, even if they hadn’t been recruited by Wagner, the expert said. But there’s no reason to expect an explosive spike in crime because a significant number of the ex-convicts probably can refrain from breaking the law for some time, especially if they were well-paid by Wagner, the expert said.

He expects crime rates to rise after the war, but not necessarily due to the use of convicts. It’s something that usually happens following conflicts, he said.

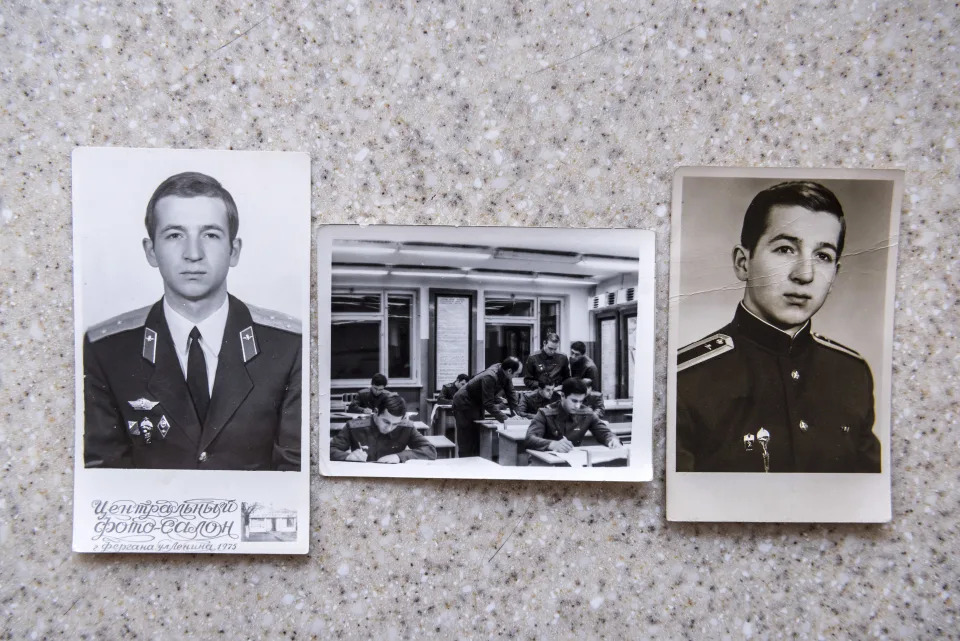

The Soviet Union sent 1.2 million convicts to fight in World War II, according to a 2020 research paper by Russia’s state penitentiary service. It did not say how many returned, but the criminology expert told AP a “significant number” ended up behind bars again after committing new crimes for years afterward.

Romanova from Russia Behind Bars says there have been many troubling episodes involving convicts returning to civilian life after a stint in Ukraine.

Law enforcement and justice officials who spent time and resources to prosecute these criminals can feel humiliated by seeing many of them walk free without serving their sentences, she said.

“They see that their work is not needed,” Romanova added.

Some convicts who are caught committing crimes after returning home sometimes try to turn the tables on police by accusing them of discrediting those who fought in Ukraine — now a serious crime in Russia, she said.

Asked if that deters those in law enforcement, Romanova said: “You bet. A prosecutor doesn’t want to go to prison for 15 years.”

Yana Gelmel, lawyer and rights advocate who also works with convicts, said in an interview that those returning from Ukraine often act with bravado and bluster, demanding special treatment for having “defended the motherland.”

She paints a grim life in Russia’s prisons, with rampant and incessant violence, extreme isolation, constant submission to guards and a strict hierarchy among inmates. For prisoners in those conditions, “what would his mental state be?” Gelmel asked.

Add in the trauma of being thrown into battle — especially in places like Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine, the longest and bloodiest of the conflict, where Wagner forces died by the thousands,

“Imagine -– he went to war. If he survived … he witnessed so much there. In what state will he return?” she added.

Meanwhile, prison recruiting for duty in Ukraine apparently continues — just not by Wagner, rights groups say. The Defense Ministry is now seeking volunteers there instead and offering them contracts.

Romanova said the ministry had recruited nearly 15,000 convicts as of June, although officials there did not respond to a request for comment.

Unlike Wagner, the Defense Ministry soon will have legal grounds -– laws allowing for enlisting convicts into contractual service have been swiftly approved by the parliament and signed by Putin last week.

And unlike Wagner, the ministry is offering 18-month contracts, but many recruits haven’t been given anything to sign, ending up in a precarious position, Romanova said.

Enthusiasm among inmates to serve hasn’t waned, she said, even after thousands were killed on the battlefield.

“Russian roulette is our favorite game,” Romanova said, grimly. “National entertainment.”