The New York Times

Russia Sought to Kill Defector in Florida

Ronen Bergman, Adam Goldman and Julian E. Barnes – June 19, 2023

As President Vladimir Putin of Russia has pursued enemies abroad, his intelligence operatives now appear prepared to cross a line that they previously avoided: trying to kill a valuable informant for the U.S. government on American soil.

The clandestine operation, seeking to eliminate a CIA informant in Miami who had been a high-ranking Russian intelligence official more than a decade earlier, represented a brazen expansion of Putin’s campaign of targeted assassinations. It also signaled a dangerous low point even between intelligence services that have long had a strained history.

“The red lines are long gone for Putin,” said Marc Polymeropoulos, a former CIA officer who oversaw operations in Europe and Russia. “He wants all these guys dead.”

The assassination failed, but the aftermath in part spiraled into tit-for-tat retaliation by the United States and Russia, according to three former senior U.S. officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss aspects of a plot meant to be secret and its consequences. Sanctions and expulsions, including of top intelligence officials in Moscow and Washington, followed.

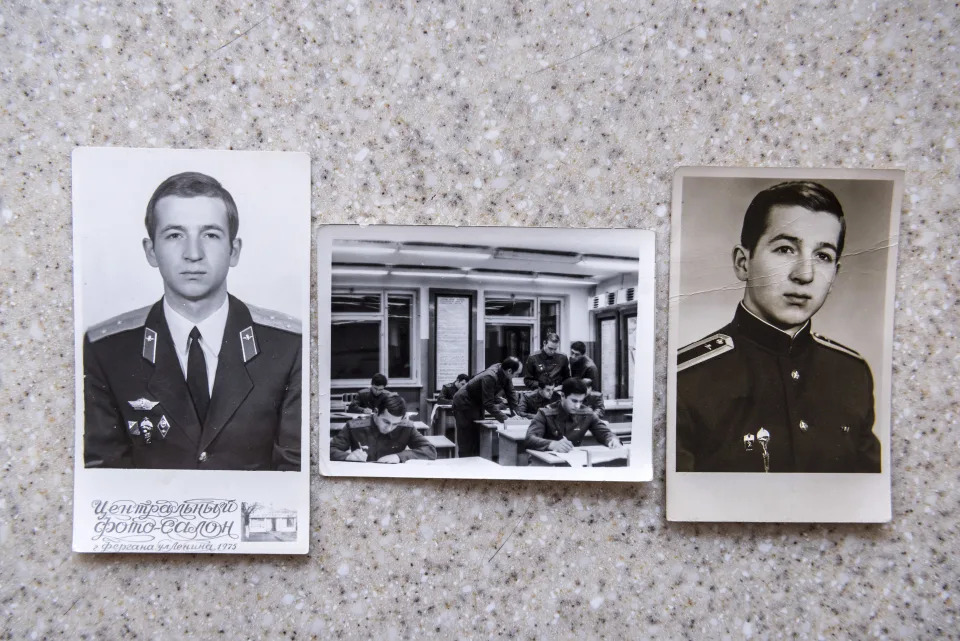

The target was Aleksandr Poteyev, a former Russian intelligence officer who disclosed information that led to a yearslong FBI investigation that in 2010 ensnared 11 spies living under deep cover in suburbs and cities along the East Coast. They had assumed false names and worked ordinary jobs as part of an ambitious attempt by the SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence agency, to gather information and recruit more agents.

In keeping with an Obama administration effort to reset relations, a deal was reached that sought to ease tensions: Ten of the 11 spies were arrested and expelled to Russia. In exchange, Moscow released four Russian prisoners, including Sergei Skripal, a former colonel in the military intelligence service who was convicted in 2006 for selling secrets to Britain.

The bid to assassinate Poteyev is revealed in the British edition of the book “Spies: The Epic Intelligence War Between East and West,” to be published by an imprint of Little, Brown on June 29. The book is by Calder Walton, a scholar of national security and intelligence at Harvard. The New York Times independently confirmed his work and is reporting for the first time on the bitter fallout from the operation, including the retaliatory measures that ensued once it came to light.

According to Walton’s book, a Kremlin official asserted that a hit man, or a Mercader, would almost certainly hunt down Poteyev. Ramón Mercader, an agent of Josef Stalin’s, slipped into Leon Trotsky’s study in Mexico City in 1940 and sank an ice ax into his head. Based on interviews with two U.S. intelligence officials, Walton concluded the operation was the beginning of “a modern-day Mercader” sent to assassinate Poteyev.

The Russians have long used assassins to silence perceived enemies. One of the most celebrated at SVR headquarters in Moscow is Col. Grigory Mairanovsky, a biochemist who experimented with lethal poisons, according to a former intelligence official.

Putin, a former KGB officer, has made no secret of his deep disdain for defectors among the intelligence ranks, particularly those who aid the West. The poisoning of Skripal at the hands of Russian operatives in Salisbury, Britain, in 2018 signaled an escalation in Moscow’s tactics and intensified fears that it would not hesitate to do the same on American shores.

The attack, which used a nerve agent to sicken Skripal and his daughter, prompted a wave of diplomatic expulsions across the world as Britain marshaled the support of its allies in a bid to issue a robust response.

The incident set off alarm bells inside the CIA, where officials worried that former spies who had relocated to the United States, like Poteyev, would soon be targets.

Putin had long vowed to punish Poteyev. But before he could be arrested, Poteyev fled to the United States, where the CIA resettled him under a highly secretive program meant to protect former spies. In 2011, a Moscow court sentenced him in absentia to decades in prison.

Poteyev had seemed to vanish, but at one point, Russian intelligence sent operatives to the United States to find him, though its intentions remained unclear. In 2016, the Russian news media reported that he was dead, which some intelligence experts believed might be a ploy to flush him out. Indeed, Poteyev was very much alive, living in the Miami area.

That year, he obtained a fishing license and registered as a Republican so he could vote, all under his real name, according to state records. In 2018, a news outlet reported Poteyev’s whereabouts.

The CIA’s concerns were not unwarranted. In 2019, the Russians undertook an elaborate operation to find Poteyev, forcing a scientist from Oaxaca, Mexico, to help.

The scientist, Hector Alejandro Cabrera Fuentes, was an unlikely spy. He studied microbiology in Kazan, Russia, and later earned a doctorate in the subject from the University of Giessen in Germany. He was a source of pride for his family, with a history of charitable work and no criminal past.

But the Russians used Fuentes’ partner as leverage. He had two wives: a Russian living in Germany and another in Mexico. In 2019, the Russian wife and her two daughters were not allowed to leave Russia as they tried to return to Germany, court documents say.

That May, when Fuentes traveled to visit them, a Russian official contacted him and asked to see him in Moscow. At one meeting, the official reminded Fuentes that his family was stuck in Russia and that maybe, according to court documents, “we can help each other.”

A few months later, the Russian official asked Fuentes to secure a condo just north of Miami Beach, where Poteyev lived. Instructed not to rent the apartment in his name, Fuentes gave an associate $20,000 to do so.

In February 2020, Fuentes traveled to Moscow, where he again met with the Russian official, who provided a description of Poteyev’s vehicle. Fuentes, the Russian said, should find the car, obtain its license plate number and take note of its physical location. He advised Fuentes to refrain from taking pictures, presumably to eliminate any incriminating evidence.

But Fuentes botched the operation. Driving into the complex, he tried to bypass its entry gate by tailgating another vehicle, attracting the attention of security. When he was questioned, his wife walked away to photograph Poteyev’s license plate.

Fuentes and his wife were told to leave, but security cameras captured the incident. Two days later, he tried to fly to Mexico, but U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers stopped him and searched his phone, discovering the picture of Poteyev’s vehicle.

After he was arrested, Fuentes provided details of the plan to American investigators. He believed the Russian official he had been meeting worked for the FSB, Russia’s internal security service. But covert operations overseas are usually run by the SVR, which succeeded the KGB, or the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency.

One of the former officials said Fuentes, unaware of the target’s significance, was merely gathering information for the Russians to use later.

Fuentes’ lawyer, Ronald Gainor, declined to comment.

The plot, along with other Russian activities, elicited a harsh response from the U.S. government. In April 2021, the United States imposed sanctions and expelled 10 Russian diplomats, including the chief of station for the SVR, who was based in Washington and had two years left on his tour, two former U.S. officials said. Throwing out the chief of station can be incredibly disruptive to intelligence operations, and agency officials suspected that Russia was likely to seek reprisal on its American counterpart in Moscow, who had only weeks left in that role, the officials said.

“We cannot allow a foreign power to interfere in our democratic process with impunity,” President Joe Biden said at the White House in announcing the penalties. He made no mention of the plot involving Fuentes.

Sure enough, Russia banished 10 American diplomats, including the CIA’s chief of station in Moscow.