Associated Press

New swamp: Lobbyist tied to Perry seeks energy firm bailout

Matthew Daly and Richard Lardner, Associated Press May 29, 2018

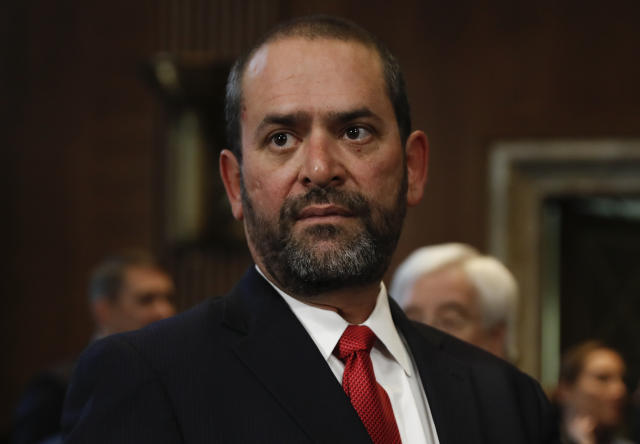

January 19, 2017 photo: Jeff Miller attends then Energy Secretary-designate Rick Perry’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on Capitol Hill in Washington. President Donald Trump has talked frequently about ‘draining the swamp’ of inside dealers in Washington. But lobbyist Jeff Miller might be considered part of the new swamp. Miller, who is a close friend of Energy Secretary Rick Perry, is pushing the administration for a bailout worth billions of dollars for FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt coal and nuclear power company. Miller has earned $3.2 million in just over a year as a lobbyist for clients that include several large energy companies. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

January 19, 2017 photo: Jeff Miller attends then Energy Secretary-designate Rick Perry’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on Capitol Hill in Washington. President Donald Trump has talked frequently about ‘draining the swamp’ of inside dealers in Washington. But lobbyist Jeff Miller might be considered part of the new swamp. Miller, who is a close friend of Energy Secretary Rick Perry, is pushing the administration for a bailout worth billions of dollars for FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt coal and nuclear power company. Miller has earned $3.2 million in just over a year as a lobbyist for clients that include several large energy companies. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Washington (AP) — At a West Virginia rally on tax cuts, President Donald Trump veered off on a subject that likely puzzled most of his audience.

“Nine of your people just came up to me outside. ‘Could you talk about 202?'” he said. “We’ll be looking at that 202. You know what a 202 is? We’re trying.”

One person who undoubtedly knew what Trump was talking about last month was Jeff Miller, an energy lobbyist with whom the president had dined the night before. Miller had been hired by FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt power company that relies on coal and nuclear energy to produce electricity. His assignment: push the Trump administration to use a so-called 202 order — named for a provision of the Federal Power Act — to secure a bailout worth billions of dollars.

Although Trump didn’t agree to the plan — he still hasn’t — for Miller, a president’s public declaration of interest amounted to a job well done.

How a single lobbyist helped carry a long-shot idea from obscurity to the presidential stage is a twisty journey through the new swamp of Trump’s Washington. Rather than clearing out the lobbyists and campaign donors that spend big money to sway politicians, Trump and his advisers paved the way for a new cast of powerbrokers who have quickly embraced familiar ways to wield influence.

Miller is among them. A well-connected GOP fundraiser, he served in the past as an adviser to California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and to Texas Gov. Rick Perry, also a close friend. He ran Perry’s unsuccessful presidential campaign in 2016. And when Trump tapped Perry to lead the Energy Department, Miller shepherded his friend through confirmation, sitting behind him, next to the nominee’s wife, at the Senate hearing.

When Perry came to Washington, Miller did, too. He launched his firm, Miller Strategies, early last year and began lobbying his friend and other Washington officials.

Besides Perry, Miller is close to other Trump-era power players. He is among House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s best friends, their relationship dating back decades to Miller’s days in California. In more recent years, Miller developed a friendship with Vice President Mike Pence adviser Marty Obst.

Obst says the two began working closely together when Perry and Pence held leadership roles at the Republican Governors Association several years ago. “He’s very influential in Washington, a leading fundraiser,” Obst said of Miller in a brief interview.

Now, after 14 months in business, the 43-year-old has collected more than $3.2 million from a roster of clients that includes several of the nation’s largest energy companies, among them Southern Co., a nuclear power plant operator headquartered in Atlanta, and Texas-based Valero Energy, according to federal filings.

Miller also has continued to raise money for GOP politicians. He contributed nearly $37,000 of his own over the past year to Republicans, including Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas and Greg Pence of Indiana, who’s seeking the congressional seat once held by his younger brother, the vice president, according to federal campaign records.

He is an active supporter of America First Action, a pro-Trump super PAC that raised $4.7 million in the first three months of 2018. That work earned him a spot at dinner with Trump, McCarthy and other GOP donors in the upscale City Center complex blocks from the White House.

“What happened to draining the political swamp?” asks Dick Munson with the Environmental Defense Fund, who said he sees FirstEnergy and other coal operators “grasping” for bailouts to solve problems of their own making. “It seems when you don’t have solid arguments, you hire well-paid lobbyists and make huge political contributions.”

Miller declined to comment for this story.

Brian Walsh, president of America First Action, said Miller raises money for the group on a volunteer basis. Miller, who lives in Texas, spent years outside of Washington independently developing an “amazing” network of connections, Walsh said. He described Miller as a “straight shooter” and rejected the notion that he is cashing in on Trump’s election and Perry’s ascension to energy chief.

“He doesn’t play games with people,” Walsh said of Miller.

But Tim Judson, executive director of Nuclear Information and Resource Service, an activist group, called Miller’s involvement in the bailout request the ultimate “Washington swamp” situation.

“We have a special-interest appeal by FirstEnergy, a top lobbyist dining with the president, and that same lobbyist is raising money for a pro-Trump super PAC and asking for ’emergency action’ from someone whose presidential campaign he ran,” Judson said.

Miller registered as a lobbyist in Washington in February 2017, just after Trump took office. He was hired by FirstEnergy in July 2017. Lobbying disclosure records show he was paid to target the highest levels of American government: the White House — to include the offices of Trump and Pence — and Perry’s Energy Department. Miller has earned $330,000 from FirstEnergy since last year, making him one of the company’s highest-paid outside lobbyists.

The coal industry’s top priority at the time was seizing on the campaign promises Trump had made — he pledged repeatedly to bring back coal jobs — to ask for unprecedented federal assistance.

Ohio-based Murray Energy Corp., the nation’s largest privately owned coal-mining company, and its largest customer, FirstEnergy, pushed the Energy Department for an emergency order, a measure typically reserved for war or natural disasters. Among other measures, the intervention would have exempted power plants from obeying a host of environmental laws and would have spent billions to keep coal-fired plants open, an unprecedented federal intervention in the nation’s energy markets.

CEO Robert Murray and Charles Jones, CEO of FirstEnergy’s parent company, met with Trump in West Virginia to discuss the request, informing the president that the power company was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Despite the high-powered lobbying, Perry rejected the request in August, saying the emergency order wasn’t the right mechanism. He offered another option, asking federal energy regulators to approve a plan that would reward nuclear and coal-fired power plants for adding reliability to the nation’s power grid. But the independent Federal Energy Regulatory Commission rejected the plan in January, saying there’s no evidence that past or planned retirements of coal-fired power plants pose a threat to grid reliability.

Soon after, FirstEnergy began pushing anew for the 202. Miller has visited the Energy Department at least twice since June, including on the day Trump delivered a speech on his energy agenda at the agency’s Washington headquarters.

The company argues the emergency order is needed to prevent premature retirement of coal and nuclear plants that “cannot operate profitably under current market conditions.” The proposal would allocate money to subsidize the company and other coal operators — an outcome the company says would avert thousands of layoffs and help ensure reliability of the electric grid up and down the East Coast.

The Ohio-based company filed for bankruptcy in late March, days after announcing it would shut down three nuclear plants in Ohio and Pennsylvania within three years. The announcement followed the planned closure of a West Virginia coal-fired plant, one of a series of closings as the coal and nuclear industries struggle to compete with electricity plants that burn natural gas.

FirstEnergy’s bid for the emergency request is widely opposed by business and environmental groups as an unfair tipping of the scales in favor of faltering energy sources.

An independent wholesaler that oversees the power grid in 13 states and the District of Columbia has said the Eastern grid is in no immediate danger. FirstEnergy can shut down its three nuclear power plants within three years without destabilizing the power grid, according to a report last month from the wholesaler, PJM Interconnection.

Still, the push for a bailout continues.

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., recently suggested that Perry consider using a Korean War-era defense law to prevent the retirement of ailing coal and nuclear units. The Defense Production Act of 1950 is intended to prioritize industries deemed vital to national security. President Harry Truman used the law to cap wages and impose price controls on the steel industry.

FirstEnergy said it supports the premise, although it says it has not specifically urged Perry to use the defense law.

Perry said the administration is looking at the defense law “very closely,” one of several options being considered.

Associated Press writer Steve Peoples contributed to this report.

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a barn that can hold up to 4,800 hogs sits at the Will-O-Bett Farm outside Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the hog operation have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a barn that can hold up to 4,800 hogs sits at the Will-O-Bett Farm outside Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the hog operation have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo In this May 21, 2018 photo, a sign opposing an industrial hog farm is displayed at a home in Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the nearby hog farm have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a sign opposing an industrial hog farm is displayed at a home in Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the nearby hog farm have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

US ARMY SIGNAL CORPS,

US ARMY SIGNAL CORPS,  U.S. ARMY PHOTO,

U.S. ARMY PHOTO,  HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES U.S. ARMY,

U.S. ARMY,  WHITE HOUSE,

WHITE HOUSE,  In this Aug. 1943 file photo, a bugler sounds taps during a memorial service while a group of G.I.s visit the graves of comrades who fell in the re-conquest of Attu Island, part of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. May 30, 2018 will mark the 75th anniversary of American forces recapturing Attu Island in Alaska Aleutian chain from Japanese forces. It was the only World War II battle fought on North American soil. (AP Photo, File)

In this Aug. 1943 file photo, a bugler sounds taps during a memorial service while a group of G.I.s visit the graves of comrades who fell in the re-conquest of Attu Island, part of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. May 30, 2018 will mark the 75th anniversary of American forces recapturing Attu Island in Alaska Aleutian chain from Japanese forces. It was the only World War II battle fought on North American soil. (AP Photo, File) Photo: Mandel Ngan, AFP/Getty Images

Photo: Mandel Ngan, AFP/Getty Images Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt testifies before the house Energy and Commerce Committee’s environmental subcommittee in the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill April 26, 2018 in Washington, D.C. The focus of nearly a dozen federal inquiries into his travel expenses, security practices and other issues, Pruitt testified about his agency’s FY 2019 budget proposal. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt testifies before the house Energy and Commerce Committee’s environmental subcommittee in the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill April 26, 2018 in Washington, D.C. The focus of nearly a dozen federal inquiries into his travel expenses, security practices and other issues, Pruitt testified about his agency’s FY 2019 budget proposal. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.