When Monica M. White was growing up, her family would travel from Detroit to visit her grandparents in Eden, North Carolina, where they kept a small store in their living room. The store came with the ever-present promise of sweets, her mother’s warnings not to eat too much junk, and her grandparents’ determination to slip her snacks nevertheless.

It was only recently—when the sociologist and University of Wisconsin professor was researching for her new book Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and Black Freedom Movement—that White’s aunt explained the store was more than just her own personal candy jar.

“It was called The Community Store. My grandfather, Kenneth, along with eight other Black farmers, co-owned a car and the store was their co-op … I knew my granddaddy was a farmer, but I had no idea he was a member of a cooperative,” said White. “To hear about the collective … I still get goosebumps even just mentioning it, because it shows the serendipity of how we study who we are.”

Freedom Farmers tells the story of how Black farmers in the Deep South and Detroit—independent farmers who owned their property, sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and urban gardeners alike—banded together to counter white racism, fight economic deprivation in an age of increasing mechanization and commercial agriculture, and articulate a different vision of the future.

Many of these groups were founded in remote places that were hotbeds for grassroots labor agitation. Take Mississippi’s North Bolivar County Farm Collective (NBCFC). It was formed in 1965 when a group of Black farmers, many of whom were tractor drivers on a white-owned plantation, turned off their engines to demand a better hourly wage. After they were fired and evicted from their homes, they built a temporary tent settlement, Strike City, close to the plantation.

Two years later, the NBCFC was up and running, with its members loaning land, tools, and divvying up the resources and work. The collective fed farmers and their families, provided children with clothing so they could attend school, and launched conversations about the need to disrupt the entire food system—from decisions about what to plant to how to keep the power to process food out of factories.

Freedom Farmers is not your conventional Civil Rights narrative, couched in terms of campaigns for voting rights, school desegregation, and lunch counter seats, though there are familiar historical figures: W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, and Fannie Lou Hamer, whose Freedom Farm Cooperative gave the book its title. It’s a timely, connective, and expansive book; one that reframes the whiteness of agricultural history and calls us to remember the fact that the Black freedom struggle is an ongoing labor movement in places far and wide.

It also locates Black farmers in a Civil Rights narrative that goes beyond their historic and continuing legal struggles against USDA discrimination. Freedom Farmers moves beyond stories of subsistence and survival; it centers Black farmers as unsung food justice advocates and organic intellectuals who imagined better communities, food systems, and politics. And then, depending on one another, they started building.

Civil Eats spoke with White about the book, the ethos of Black farming communities, and why she coined the term “collective agency.”

This book made me realize how much of Civil Rights history really focuses on the urban South. What did you learn about rural folks and Black farmers, specifically?

Doing this work on rural Black Southerners flipped what I thought I knew about the South. When we were kids in Detroit, [my friends and I] would talk about what we wouldn’t do if we lived in the South and how we wouldn’t put up with [racism]. That was an overly simplistic view of how oppression manifests and people’s reaction and responses to it. One thing that I have fallen so in love with is the farmer’s freedom. There’s a certain kind of freedom that people who produce food have; they feel a sense of agency. And I don’t think it’s ever discussed when we talk about who farmers are.

I learned the genius of what it means to be a farmer, especially a Southern Black farmer. For example, Ben Burkett [of the National Family Farm Coalition] can look at a bag of seeds and tell you how many bushels he’ll get out of that, what the profit will be. Farmers don’t get credit for knowing applied mathematics.

I’m also fascinated by what rural Southern communities offered us in terms of open methods of communications—the way they supported each other, organized, and cared for each other. I feel like this book taught me a lot about the South that I didn’t understand but came to know through meeting Black folks who were raised there, but (unlike my family) never left.

You define “farmer” broadly, to include those who don’t own the land but work it.

When I first came to [the University of] Wisconsin, I presented my early ideas on what has become the book. One of my colleagues said, “You use ‘gardener’ and ‘farmer’ interchangeably, and I think you need to really [differentiate].’ In the ag language, a gardener is someone who does it for a hobby. A farmer has a certain percentage of land, a certain percentage of their income, a certain percentage of land ownership. In a broad sense, I wanted to complicate the idea of farmers only being those who own the land. For me, the expansive definition really captures the people who feed us, the people who stand out in the weather and the bugs and all conditions to make sure that we have food—often at their own expense.

The book describes a heartbreaking but brief episode when landless Black farmers occupied an abandoned military base in 1966 Mississippi. That kind of protest seems like it was within the Civil Rights strategic playbook, but with very different “characters.”

When I found out about this story, it wasn’t too long after the Bundys and white nationalists occupied federal land in the West and didn’t have a license. I thought about how different we treated them from how we treated the sharecroppers and seasonal workers who occupied the Greenville Air Force Base.

In January ’66, about 70 folks occupied an abandoned Air Force base and they were like, “Look, this is federal land, we pay federal taxes, and so we want to use this space as a strategy for our survival.” They were unemployed or [some] may have been fired because of their political inclinations or efforts to vote. So folks brought in blankets and stoves and all kinds of resources. Their demands were: “We want land, we want food, we want jobs, we want shelter.”

And please be clear: They said, “We’re not asking for a handout, we’re asking for an opportunity to uplift ourselves, our family, and our community.” They were evicted in a violent sort of extraction [as opposed to the years-long conflict in which Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy illegally grazed on public land and negotiated with the Bureau of Land Management]. These were folks who were asking for land to grow food.

After the eviction, federal attention turned to the state and resources were then allocated to Mississippi in terms of food, shelter, and housing. It’s important to recognize that this occupation was right in that area where Hamer and her freedom farm was and in the Mississippi Delta. There was this air of resistance and resilience in the region.

You coin the term “collective agency” to describe how Black farmers mobilize, whether that’s in Mississippi or Detroit. Can you say more about that?

I didn’t feel like there was a way to help us understand what happens in cities like Detroit, where the economic bottom is falling out. People are left to fend for themselves, and they collectively engage in something that impacts or changes the political, economic, and social context of their future.

-

Support from readers like you is what keeps Civil Eats going.

Please consider making a year-end donation or signing up for an annual subscription if you haven’t already.

Thank you from the Civil Eats team!

Agency is mostly defined as a very individual thing. The language has to capture that as an individual, yes, you make the decision that you’re going to grow food. But what about when several people decide they want to [farm] as a strategy for increasing access to nutrient-rich food and pool our resources together? What happens when we care about each other in terms of health, education, safety, security, and wellness and there’s this collective decision to move in these directions? I couldn’t find a way to explain it other than “collective agency.”

In my research in Detroit, folks would tell me, “I have a backyard garden … and I contribute to the food that’s grown in the community garden, I don’t harvest anything there. I do it because this is for us.” That’s a collective agency that we don’t talk about.

How do you connect Black farmers to other seminal Black thinkers in the book? You have a different take on the relationship between W.E.B. Du Bois (who is often framed as an elitist who only wanted to educate the “talented tenth,”) and Booker T. Washington, (who is often framed as telling Black people to stay on the land and not aim higher). Both frames lack nuance.

I was really cautious about this. But I thought: If Booker T. was talking about farmers, was that not 90 percent of the population? If Du Bois is talking about the talented tenth, what would happen if the two of them were actually in a room together to say, “Here’s 90, here’s 10, and this is how we’re going to get free.” Then as I read more and more about Du Bois, I realized that he stopped talking about the talented tenth, and really started investing in thinking about cooperatives in ways that people haven’t really understood until Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s book Collective Courage came out.

We don’t have to do binaries. What tools can we use from Washington? What tools can we use from Du Bois, George Washington Carver, and Hamer?

What’s your relationship to the soil? Because this book is chipping away at the idea that, after slavery, Black people wanted to remove themselves from agriculture.

I really love this question. I have some soil from [New Orleans’] Congo Square in a little container. I have soil from Hamer’s final resting place. I have soil from Burkett. I have soil from Tuskegee. Soil is a substance that I greatly revere. I have an immense amount of respect for the stories that soil holds. It’s not unlike the Equal Justice Initiatives Legacy Museum’s remembrance project [where people collect soil from places where people were lynched]. My connection to the soil is that I see freedom and a medium through which birth and death are connected.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

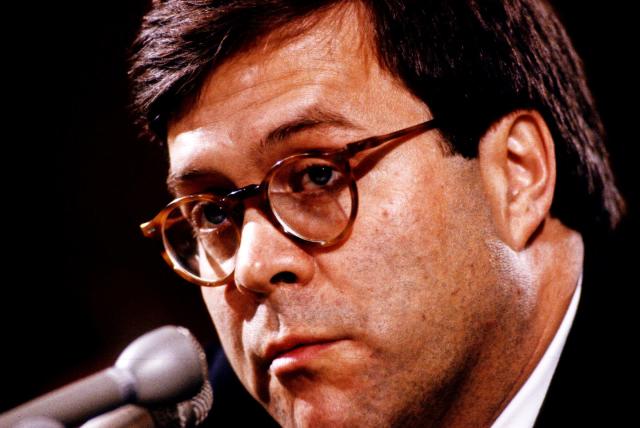

Author photo by G. Greg Wells.

Though the Wepking’s children, a three-year-old and his baby sister, are with their grandmother on this day, a countertop collection of toy tractors suggests that the kids usually fill the kitchen with life.

Though the Wepking’s children, a three-year-old and his baby sister, are with their grandmother on this day, a countertop collection of toy tractors suggests that the kids usually fill the kitchen with life. They also transitioned the spring grain mix to include spring wheat for bread flour, and last year, they started growing buckwheat. “So we’re looking at more of a six-to-seven-year rotation as opposed to four to five,” John says.

They also transitioned the spring grain mix to include spring wheat for bread flour, and last year, they started growing buckwheat. “So we’re looking at more of a six-to-seven-year rotation as opposed to four to five,” John says.