Bloomberg – Politics

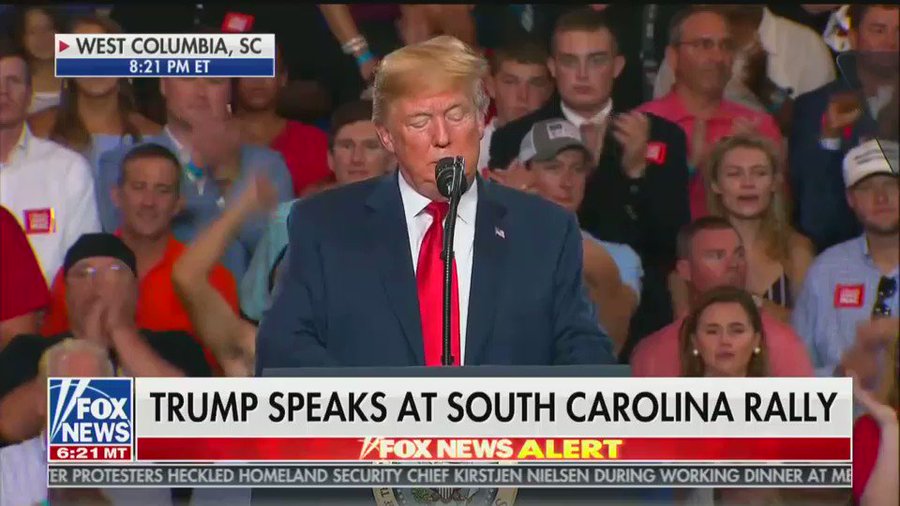

Koch Brothers-Linked Group Declares New War on Unions

The Supreme Court decision to kill “agency” fees triggers a massive campaign to accelerate the demise of the American labor movement.

By Josh Eidelson June 27, 2018

Supreme Court Has Brought on New Era of Labor Unrest, Rep. Ellison Says

U.S. Supreme Court Rules 5-4 Against Unions on Mandatory Fees

Following a U.S. Supreme Court decision that millions of public sector workers can stop paying union fees, a group tied to Republican billionaires long opposed to organized labor and its support of the Democratic Party has pledged to build on the landmark ruling to further marginalize employee representation.

The conservative nonprofit Freedom Foundation said that starting Wednesday, it will deploy 80 people to a trio of West Coast union bastions: California, Oregon and its home state of Washington. The canvassers were hired in March and trained this month, according to internal documents reviewed by Bloomberg News. The goal of the multi-pronged campaign is to shrink union ranks in the three states by 127,000 members—and to offer an example for similar efforts targeting unions around the country.

“Their employer isn’t going to tell them, and the union isn’t going to tell them,” said the anti-union group’s labor policy director, Maxford Nelsen. “So it falls to organizations like the Freedom Foundation to take up that mantle and make sure that public employees are informed of their constitutional rights.”

President George W. Bush (left) announces the nomination of Samuel Alito (right) in 2005. Photographer: Jay Clendenin/Bloomberg

President George W. Bush (left) announces the nomination of Samuel Alito (right) in 2005. Photographer: Jay Clendenin/Bloomberg

The 5-4 Supreme Court ruling, with a majority of all-Republican appointees, threatens one of the last strongholds of America’s vanishing labor movement, a reliable source of support for the Democratic Party. Before today, public sector unions could require non-members to pay “agency” fees to fund collective bargaining efforts on behalf of all employees, since they benefit equally from representation. Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito—appointed by President George W. Bush—said such a requirement violated employees’ rights under the First Amendment. The majority held that workers must affirmatively opt-in to pay any fees, making it more likely that unions will lose funding and thus the ability to negotiate wages and benefits on behalf of workers.

The Freedom Foundation has been waiting for this moment. In February, it began acquiring lists of workers and identifying public employees to feature in anti-union videos. This month, it has been assembling materials to provide to sympathetic local-government human resources departments and readying a toll-free call center.

“It just so happens that unions are the ones that stick up for the working class—whether we represent them or not.”

Now that the ruling has come to pass, the group plans a flood of social media, mail, email, cable television ads, op-eds and phone calls to spread the news about employees’ opportunity to cease paying union fees. Along with going door-to-door, the anti-union activists plan to visit government buildings at which public employees work.

Labor leaders said their members are ready to withstand the barrage. “They’re really not advocating for the employees at all—they’re advocating for unions to lose their power,” said Bob Schoonover, a heavy equipment mechanic for the city of Los Angeles who serves as president of a Service Employees International Union local there. “They want to silence the working class. It just so happens that unions are the ones that stick up for the working class—whether we represent them or not.” Schoonover said his union has been planning for the possibility of the anti-union ruling for years. “We feel that we’re as prepared as we can be.”

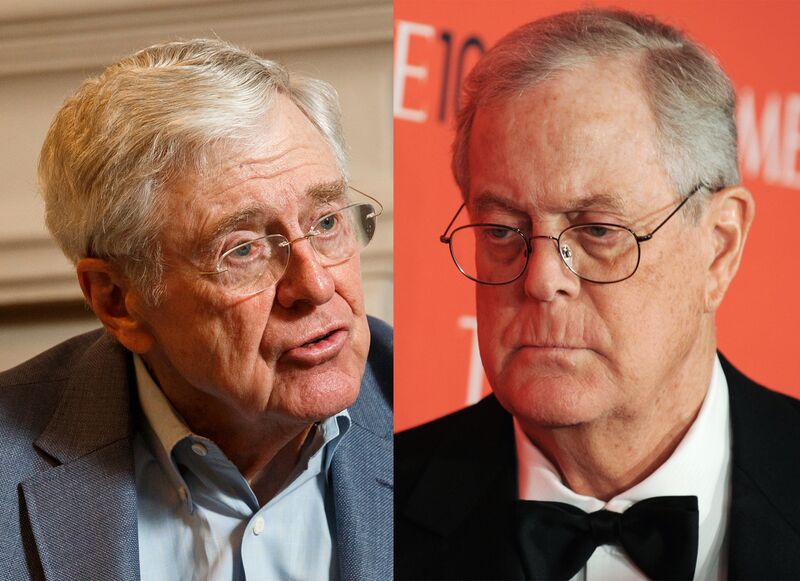

Charles (left) and David Koch. Photographer: Getty Images

Charles (left) and David Koch. Photographer: Getty Images

Led by a former executive of the lobbying group, Building Industry Association of Washington, the Freedom Foundation reported a 2016 budget of $4 million. Its current assault on unions is modeled on past efforts that targeted home health aides, who in 2014 were given the option of not paying fees, and other government workers, who had a choice of paying full dues or smaller representation fees.

Nelsen declined to identify any of its donors, which he said include businesses, foundations and individuals “from all different walks of life.” All donations are “made by those who believe in our mission,” he said.

However, tax filings reveal a who’s-who of wealthy conservative groups.

Among them are the Sarah Scaife Foundation, backed by the estate of right-wing billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife; Donors Trust, which has gotten millions of dollars from a charity backed by conservative billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch; from the Richard and Helen DeVos Foundation, backed by the family of U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos; and the State Policy Network, which has received funding from Donors Trust and is chaired by a vice president of the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation. Meredith Turney, a spokeswoman for the State Policy Network, Lawson Bader, chief executive officer and president of Donors Trust, and Liz Hill, a spokeswoman for the Department of Education, declined to comment on fundraising or donations. Scaife and Koch representatives didn’t immediately return requests for comment.

In records obtained by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, the Bradley Foundation reported having given the Freedom Foundation $1.5 million in 2015 “to expand its union transparency & reform project,” including by opening a Portland, Oregon, office. In Bradley Foundation records obtained by the nonprofit Center for Media and Democracy, the foundation’s staff recommended providing funds to the Freedom Foundation because West Coast union money “is used to subsidize the left’s national agenda and obstruct the mission and program interests of the Bradley Foundation and its allies.”

The Bradley Foundation praised the Supreme Court ruling while declining to comment on the Freedom Foundation.

“They don’t want outsiders to hurt their freedom to earn a better life.”

Past Freedom Foundation literature seeks to turn workers against unions by highlighting six-figure salaries allegedly paid to union executives, as well as sending out postcards with images of a dingy hotel and a warning echoing an Eagles song: “You can sign up anytime you like but you can never leave!”

According to the group’s documents, targets for its new “insurgency” campaign include corrections officers and teachers, who will be out of school for the summer and thus “have no interaction with their union.” Because the Oregon chapter of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or Afscme, has been preparing members by “aggressively messaging” them, the anti-union group’s documents state, taking a more patient, less-aggressive approach with those workers will help to “demonize” the union.

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a Michigan-based nonprofit that, like the Freedom Foundation, is a member of the State Policy Network and has received funding from Donors Trust, has launched a “My Pay, My Say” website that by Wednesday afternoon was informing public employees of their rights under the Supreme Court decision. The website offers an automated system for workers to generate letters to their unions opting out of paying fees or dues. Prior to Wednesday’s ruling, the Americans for Prosperity Foundation, the 501(c)3 tied to the Koch-backed American for Prosperity, had already launched paid Facebook ads announcing that “Workers’ rights may soon be restored” and promoting the mypaymysay.com website.

Randi Weingarten, of the American Federation of Teachers, speaking at the 2008 Democratic National Convention. Photographer: Matthew Staver/Bloomberg

Randi Weingarten, of the American Federation of Teachers, speaking at the 2008 Democratic National Convention. Photographer: Matthew Staver/Bloomberg

Afscme, which in 2015 privately estimated that half the workers it represents could be “on the fence” about whether to pay dues, said it’s trained 25,000 members who’ve helped conduct 800,000 face-to-face conversations with co-workers on the topic.

The American Federation of Teachers said that more than 500,000 of its members in the 10 states most affected by the ruling have recommitted to their union over the past six months, and that educators won’t be swayed by anti-union ads or canvassers funded by right-wing groups.

“When members find out who’s pulling the strings, they get pissed, because they don’t want outsiders to hurt their freedom to earn a better life,” AFT president Randi Weingarten said in an email. “We are confident that when members start getting harassed by these outside groups, they’ll be ready—not only to reject their assault but to become more active in their union.”

The “No. 1 goal” is to slash union support for the Democratic Party.

Other union supporters are looking to a range of strategies—including aggressive activism such as successful teacher strikes that roiled so-called right-to-work states this year, enticing members with exclusive benefits such as tuition discounts, and getting state laws passed that ease the organizing process.

But while such groups as Nevada’s casino union have flourished in the absence of mandatory fees, the big picture for organized labor is bleak following the high court’s ruling. In states with “right-to-work” laws, where it’s illegal to require workers to fund unions that are required to represent them, employees are already half as likely to have union representation—or less.

Such laws, and the Supreme Court opinion, have significant electoral consequences. “Right-to-work” laws already reduce the Democratic Party’s share of a state’s presidential vote by 3.5 percent and cut turnout by 2 percent to 3 percent, according to a working paper published this year by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Those policies, often put in place by Republican-controlled state legislatures, help dampen union political participation—the ultimate goal of anti-union initiatives at all levels of government, labor supporters said.

In a 2016 speech to American for Prosperity, the advocacy group backed by the Koch brothers, Freedom Foundation’s then-Oregon Coordinator Anne Marie Gurney said, “Our No. 1 stated focus is to defund the political left,” the Guardian reported. The prior year, Freedom Foundation CEO Tom McCabe authored a fundraising letter touting its “proven plan for bankrupting and defeating government unions” and addressing “a broken political culture” fueled by union dues.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Animals, too, play an integral role. The Martens raise 70 or so heifers and dry cows for nearby dairy farmers. They feed them primarily on the cover crops, crop residue, and crop by-products—clover, barley or oat residue, and corn stalks. In exchange, the animals provide manure as a natural source for soil fertility.

Animals, too, play an integral role. The Martens raise 70 or so heifers and dry cows for nearby dairy farmers. They feed them primarily on the cover crops, crop residue, and crop by-products—clover, barley or oat residue, and corn stalks. In exchange, the animals provide manure as a natural source for soil fertility.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – 2018

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – 2018 Getty Images

Getty Images