NBC News.com

Remember D-Day’s African-American Soldiers on Veterans Day

Wilson Monk (third from left) and other men from the 320th appear to be in deep thought as they peruse a document.Linda Hervieux / Wilson Monk

A few months ago I was speaking with an archivist at an Army museum who told me flatly, “There were no black men at D-Day.”

I had just explained to him that I’d spent six years researching and writing the story of D-Day’s only African-American combat unit.

The belief is pervasive that there were no soldiers of color on the beaches of France on one of the most important days of World War II. None of the many films made about D-Day like “Saving Private Ryan” show black soldiers storming Omaha Beach. Most history books don’t mention them.

It is a sore point among black veterans.

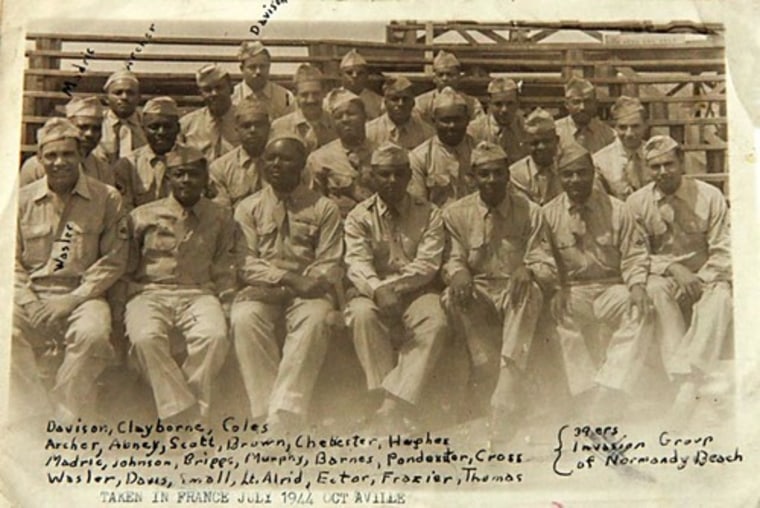

But they were there, landing under brutal fire early on June 6, 1944. The men of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion were packed tight with infantry troops aboard small metal boats that motored toward the Normandy coast obscured by smoke and fire. It was a harrowing ride, and even worse when they landed as early as 9 a.m.

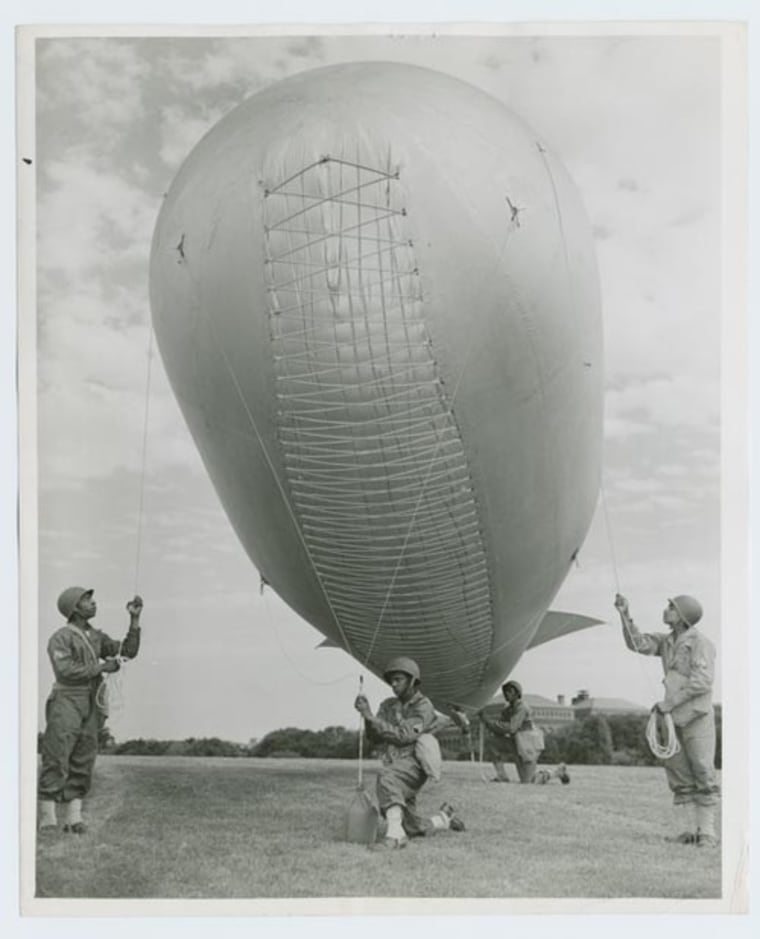

They were charged with raising a curtain of hydrogen-filled balloons over the beaches anchored to steel cables. Tucked under the 125-pound gasbags were small bombs the size of a soda can. A dive-bombing German plane that hit the cable risked being blown to bits. But until the beaches were cleared of small arms fire, the balloon flyers were infantry troops. They dug trenches, rounded up German prisoners and prayed they would survive the worst day of their lives.

On this Veterans Day, it is important that we remember that the more than 1 million African Americans in uniform in WWII were ordered to fight for freedom and democracy abroad, while at home they were mistreated in an Army segregated by race.

They suffered daily humiliations at the hands of white commanders who considered them less intelligent and courageous than white men. An Army War College study concluded the black soldier “naturally believes himself inferior to the white.” This was the reason given for assigning the vast majority of black troops to labor and service units.

An Army War College study concluded the black soldier “naturally believes himself inferior to the white.” This was the reason given for assigning the vast majority of black troops to labor and service units.

By the time the sun set on June 6, 1944, some 2,000 African Americans had landed in Normandy. They were engineers, stevedores, and gunners. They carried the wounded to safety and buried the dead. They drove ambulances, earth-movers and the trucks that would supply the front lines. Black quartermasters won praise from Gen. Dwight Eisenhower for salvaging their trucks sunk in deep water — and saving significant quantities of blood plasma and medical supplies that would save lives on Omaha Beach. Eisenhower praised the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion for carrying out its mission “with courage and determination” and said the men exposed like sitting ducks on the sand “proved an important element of the air defense team.”

RELATED: 9 Things to Know About the History of Juneteenth

The Hollywood director John Ford, who landed on Omaha with a Coast Guard film crew, watched in amazement as a black soldier unloaded supplies from a ship, ignoring the small-arms fire and mortar shells pocking the sand around him. Ford was too scared to leave his safe spot to film the soldier but he wrote, “By God, if anybody deserves a medal that man does.”

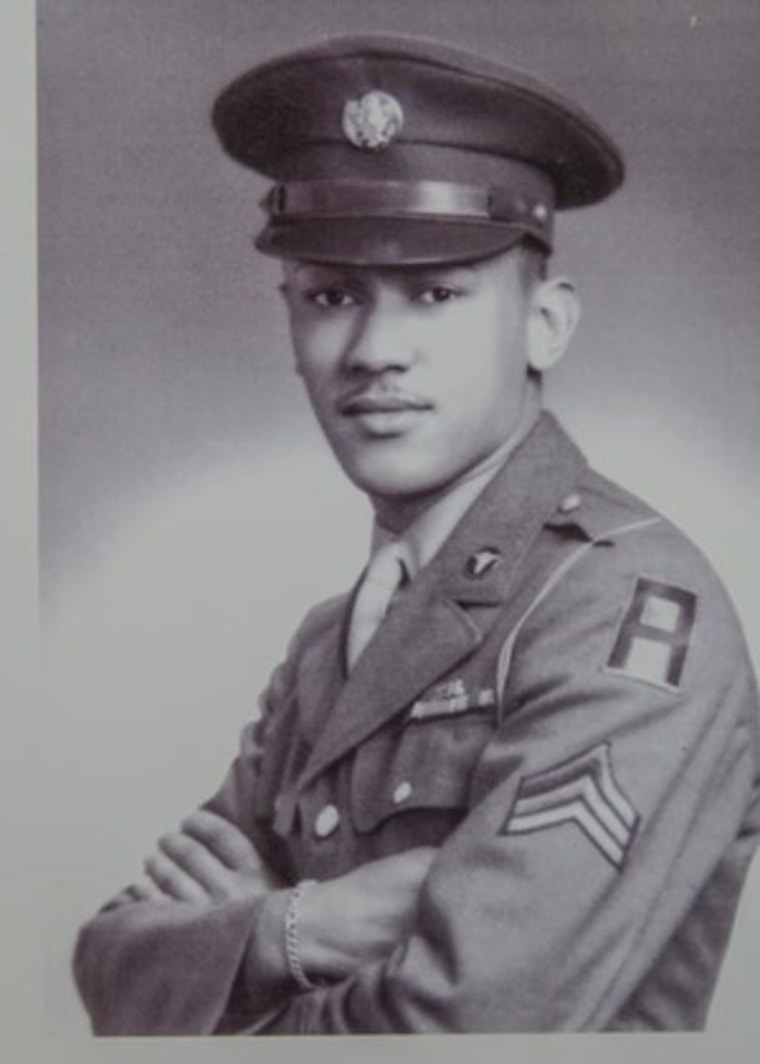

Among those brave young men steaming toward France early on D-Day was a 21-year-old medical student from West Philadelphia. Woodson didn’t wait for a draft notice. He left his studies at Lincoln University and signed up for the Army. He finished his training as a commissioned officer, but there were no positions available for him.

It was a common story: black officers in WWII were limited by quotas and the rule they not lead white officers junior to them. So he retrained as a medic with the 320th. Wounded twice as his disabled boat drifted toward Omaha, Corporal Woodson would save scores of lives until he collapsed 30 hours later. The black press dubbed him “No. 1 Invasion Hero” and Stars and Stripes wrote that Woodson and the four medics with him “covered themselves with glory on D-Day.” The black press began calling on the White House to award him the Medal of Honor.

RELATED: WWI ‘Harlem Hellfighter’ Henry Johnson to Receive Medal of Honor

A sole piece of paper exists today in the National Archives revealing that Woodson was, in fact, a candidate for the nation’s highest award for bravery. A note passed from the War Department to the White House reveals that Woodson’s commanding officer had recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest award, but that the office of a US Army general in Britain had changed the recommendation to Medal of Honor.

“This is a big enough award so that the President can give it personally, as he has in the case of some white boys,” a War Department aide wrote. The nomination was significant because no African-Americans received the Medal of Honor in World War II. After an Army study found pervasive racism was to blame for the slight and President Bill Clinton awarded seven Medals of Honor to African-Americans in 1997. Only one man was alive to shake the president’s hand.

Waverly Woodson was not among them. He had to settle for fourth place, the Bronze Star. He died in 2005 without knowing there would be another push to recognize his heroism. U.S. Rep Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) has called on the Army to approve the Medal of Honor for Woodson.

In June 2015, President Barack Obama awarded the Medal of Honor to a long-neglected hero of the trenches of France in World War I. Sgt. Henry Johnson made headlines coast to coast after single-handedly fighting off a band of Germans raiders. He was a member of New York’s 369th Infantry Regiment — the legendary Harlem Hellfighters. At a ceremony at the White House, the president recalled this long-neglected hero. “It is never too late,” he said, “to say thank you.”

Woodson’s family has begun an online petition calling for him to be awarded the Medal of Honor. For more information, go to www.lindahervieux.com.

Linda Hervieux is the author of Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War (HarperCollins), which tells the story of the only African-American combat unit to land on D-Day.