USA Today

EPA finds no safe level for two toxic ‘forever chemicals,’ found in many U.S. water systems

Kyle Bagenstose, USA TODAY – June 17, 2022

The Environmental Protection Agency stunned scientists and local officials across the country on Wednesday by releasing new health advisories for toxic “forever chemicals” known to be in thousands of U.S. drinking water systems, impacting potentially millions of people.

The new advisories cut the safe level of chemical PFOA by more than 17,000 times what the agency had previously said was protective of public health, to now just four “parts per quadrillion.” The safe level of a sister chemical, PFOS, was reduced by a factor of 3,500. The chemicals are part of a class of chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as forever chemicals due to their extreme resistance to disintegration. They have been linked to different types of cancer, low birthweights, thyroid disease and other health ailments.

In effect, the agency now says, any detectable amounts of PFOA and PFOS are unsafe to consume.

The announcement has massive implications for water utilities, towns, and Americans across the country.

The Environmental Working Group, a national environmental nonprofit, has tracked the presence of PFOA, PFOS, and other PFAS chemicals in drinking water. Because the chemicals are not yet officially regulated, water systems are not required to test for them. But their use for decades in a range of products such as Teflon and other nonstick cookware, clothing, food packaging, furniture, and numerous industrial processes, means they are widespread in both the environment and drinking water.

Scott Faber, senior vice president with the group, said this week that at least 1,943 public water supplies across the country have been found to contain some amount of PFOS and PFOA. And there are likely many more that contain the chemicals but haven’t tested, Faber said, potentially placing many millions of Americans in harm’s way.

“This will set off alarm bells for consumers, for regulators, and for manufacturers, who thought the previous (advisories) were safe,” Faber said. “I can’t find the words to explain what kind of a moment this is. … The number of people drinking what are, according to these new numbers, unsafe levels of PFAS, is going to grow astronomically.”

Previous research has found Americans have already faced widespread exposure to the chemicals for decades.

What are PFAS?: A guide to understanding chemicals behind nonstick pans, cancer fears

What’s in your blood?: Attorney suing chemical companies wants to know if it can kill you

More on EPA and your health: Is EPA prioritizing interests of chemical companies? These experts think so

More than 96% of Americans have at least one PFAS in their blood, studies show. Dangers are most studied for PFOA and PFOS, which were used heavily in consumer goods before a voluntary agreement between the EPA and industry phased them out of domestic production in the 2000s. Since then, the amount of PFOA and PFOS in the blood of everyday Americans has fallen, but scientists are now concerned about a newer generation of “replacement” chemicals that some studies show are also toxic.

Indeed, EPA on Wednesday released two additional, first-time health advisories for PFAS chemicals GenX, which has contaminated communities along the Cape Fear River in North Carolina, as well as PFBS.

For years, scientists have grown increasingly concerned about how the entire class of chemicals, which number in the thousands, may be impacting public health in the United States. In highly contaminated communities like Parkersburg, West Virginia, studies have linked PFOA to kidney and testicular cancers, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, and other serious ailments.

But other studies have found a range of PFAS may be toxic even at the extremely low levels found in the general population, potentially impacting the immune system, birth weights, cholesterol levels, and even cancer risk.

Philippe Grandjean, a PFAS researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who has called for extremely protective limits on PFAS, said the chemicals don’t have acute toxicity. Consumers shouldn’t expect to fall instantly ill from consuming amounts common in drinking water.

Instead, PFAS work in the background, with risks building up over a lifetime of consumption. His work shows PFAS can decrease the immune response in children. They may come down with more infections than they would otherwise. Vaccinations aren’t as successful, an effect that may even extend to COVID-19 vaccination, a question research is now exploring.

No single individual is likely to know when PFAS caused their illness. But public health officials can detect its presence when studying overall rates, Grandjean said.

“If increased exposures have been in a community, then there will be an increased occurrence of these adverse effects,” Grandjean said.

Even with deep experience studying PFAS, a primary reaction among Grandjean and other experts to the EPA’s Wednesday announcement was surprise. The agency has grappled with how to handle PFAS for decades and has often been criticized for a perceived lack of action. The thorniest problem is the sheer scope of PFAS: regulating the substances, particularly at very low levels, has nationwide implications for water utilities, industry, and the public.

But the EPA under the Biden administration, Faber said, is signaling they are serious about moving in that direction.

“This administration has pledged to do more, and has accomplished more, than any other,” Faber said.

In releasing the new health advisories, EPA said they fit into a larger picture under the agency’s “Strategic Roadmap.” That includes an intention to propose a formal drinking water regulation for PFOS, PFOA, and potentially other chemicals this fall. The agency also says it is taking a holistic approach to PFAS, with measures planned to clean up contamination hotspots, address PFAS in consumer products, and offer support to impacted communities.

In a press release, the agency says it is making available the first $1 billion of a total of $5 billion in grant funding from the bipartisan infrastructure law passed last year to assist communities contaminated with PFAS. Another $6.6 billion is potentially available through existing loan programs for water and sewer utilities.

“People on the front lines of PFAS contamination have suffered for far too long,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said in the release. “That’s why EPA is taking aggressive action as part of a whole-of-government approach to prevent these chemicals from entering the environment and to help protect concerned families from this pervasive challenge.”

But the EPA is already receiving pushback from various corners.

The American Chemistry Council, an industry group representing many of the companies that use PFAS, said it believes the agency’s new advisories are “fundamentally flawed.”

“ACC supports the development of drinking water standards for PFAS based on the best available science. However, today’s announcement … reflects a failure of the agency to follow its accepted practice for ensuring the scientific integrity of its process,” the council said in a release.

Meanwhile, utilities remain skeptical the agency will ultimately do enough to tackle industry and other sources of pollution.

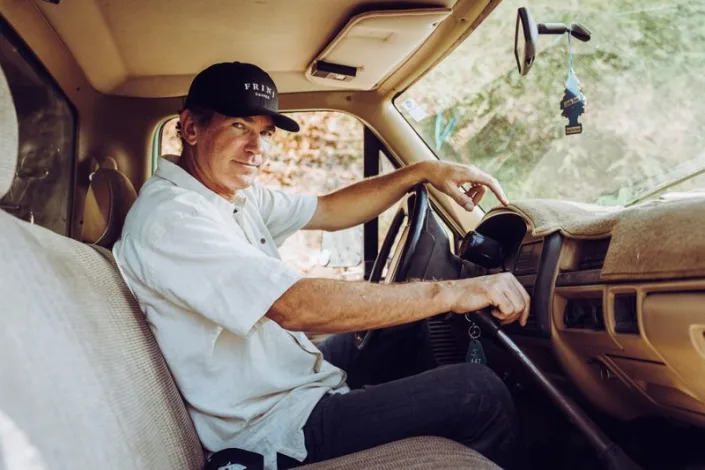

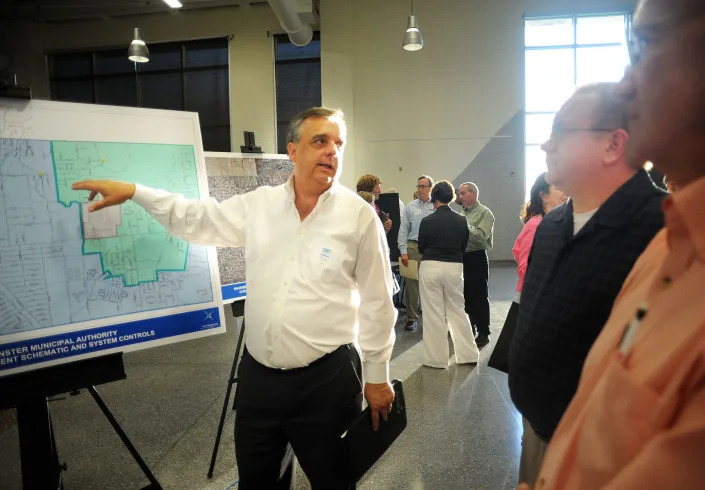

In 2016, Tim Hagey, general manager of the Warminster Municipal Authority in southeast Pennsylvania, came face to face with a nightmare for anyone tasked with providing safe drinking water to the public.

PFOA and PFOS — invisible, odorless, and dangerous — had slipped into the town’s water supply after leaking from nearby military bases. The discovery set off a years-long struggle in Warminster and neighboring communities, which decided to go beyond the EPA’s prior advisory and filter out the chemicals entirely. Hagey said they saw the writing on the wall.

“The EPA told us over the years that the more they study the chemicals, the uglier they are,” Hagey said. “Our local leaders had the courage to say, ‘We’re going to filter to zero.’”

But the decision was costly, adding up to tens of millions of dollars and requiring significant surcharges on customer water bills.

Hagey said the EPA’s new advisories are a “pleasant surprise” when it comes to protecting public health. But he’s frustrated that the Department of Defense has not yet addressed the contaminated groundwater beneath his town, contributing to ongoing cost fears.

“The aquifer has not been cleaned up. There needs to be leadership on that,” Hagey said.

Emily Remmel, director of regulatory affairs for the National Association of Clean Water Agencies, which represents wastewater authorities, said water and sewer utilities across the country are facing similar dilemmas. In many ways, PFAS contamination is unprecedented. The chemicals are everywhere, and the EPA has now found they are dangerous at levels smaller than can even be detected.

“We can’t measure to these levels, we can’t treat to these levels,” Remmel said. “So how do you deal with this from a public health standpoint?”

Remmel said she’d also like to see EPA take more action to get rid of PFAS at the source. Often they come from everyday consumer products that people use and wash down the drain.

“Washing your clothes, washing your face, washing your dishes,” Remmel said.

The costs to remove and dispose of PFAS are astronomical. A filter on a single water well can cost $500,000. Remmel said while the new funding is helpful, it’s also just a “drop in the bucket” for what’s needed across the country.

Ultimately, costs will need to be passed onto water consumers, who have already seen rates rising steeply over the past decade as utilities have invested in other priorities such as replacing lead pipes and outdated sewer infrastructure. Remmel said she wants the EPA to do a better job engaging at the local level to assist with the public health and financial burdens PFAS create.

“This should not be on the backs of municipalities, of ratepayers,” Remmel said.

Kyle Bagenstose covers climate change, chemicals, water and other environmental topics for USA TODAY.

German farmers Tim Nandelstädt (centre) and Torben Reelfs (right) push ahead with their crop planting in Ukraine despite Russia’s invasion (AFP/Tim NANDELSTAEDT)

German farmers Tim Nandelstädt (centre) and Torben Reelfs (right) push ahead with their crop planting in Ukraine despite Russia’s invasion (AFP/Tim NANDELSTAEDT) War has come to Ukraine but German farmers Torben Reelfs and Tim Nandelstaedt are planting the first sugar beets of the season on their plot of land in western Ukraine (AFP/Tim NANDELSTAEDT)

War has come to Ukraine but German farmers Torben Reelfs and Tim Nandelstaedt are planting the first sugar beets of the season on their plot of land in western Ukraine (AFP/Tim NANDELSTAEDT)