engadget

Scientists struggling to eradicate toxic ‘red tides’ from Florida’s coast

The latest outbreak has already killed thousands of marine animals.

By Andrew Tarantola August 17, 2018

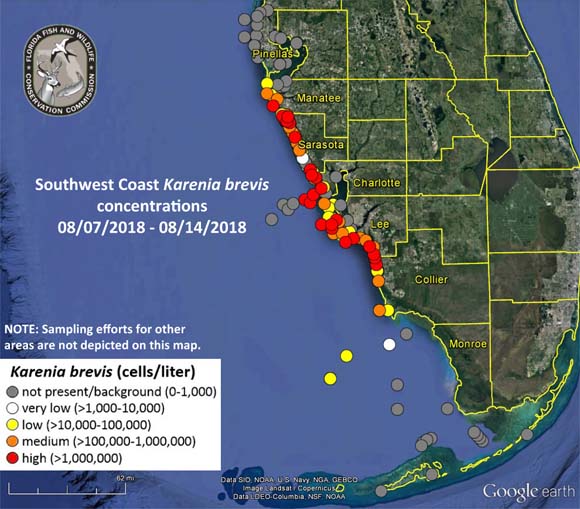

The Gulf Coast of Florida is currently suffering from a similar form of algae-induced poisoning, and has been for almost 10 months. Since October, 2017, the nearly 150 miles of state coastline — from Anna Maria Island near Bradenton down south to Naples — has been inundated with a Red Tide, specifically a massive bloom of the Karenia brevis species.

While this outbreak is not the longest on record (a bloom near Miami back in 2005-2006 ran for nearly a year and a half), this one has proven especially deadly for marine life. What makes K. brevis so dangerous is that the dinoflagellates produce potent neurotoxic substances such as brevetoxin. So far, this substance has been linked to the death of (literally) tons of fish, more than two dozen manatees a number of dolphins and even a 26-foot juvenile whale shark. Sea turtles, including the endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, have been dying at triple the nominal annual rate throughout 2018. More than 300 have already died from ingesting the brevetoxin, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

No human deaths have been reported as of yet, though the toxin can become aerosolized when waves crash up onto the beach, causing or exacerbating breathing problems. As such, while you can technically go swimming during a Red Tide, health experts warn against it. However this bloom is hitting Florida’s tourism industry hard. Governor Rick Scott on Monday announced that he would be diverting half a million dollars to local communities and businesses impacted by the drop in tourist dollars during the outbreak as well as another $100,000 towards cleanup and mitigation efforts. The especially hard-hit Lee County is slated to receive additional $900,000 in emergency relief funds.

The unicellular algae that cause Red Tides are actually fairly common throughout the world’s oceans. Though many of these blooms are non-toxic — they cause more problems via the sheer girth of their biomass which can, for example, create anaerobic environments that suffocate other organisms (so-called “fish kills”) — around a dozen species are known to produce the deadly compounds.

Interestingly, we’re not really sure what purpose these toxins actually serve. They could be a feeding deterrent, Dr. Kathleen Rein of Florida International University’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, told Engadget, or they could simply be a natural byproduct of the algae’s metabolic process.

“This organism uses a lot of energy to make these molecules,” she said. “I think there’s some other physiological, biochemical function for these molecules. But that is an area that really needs more research.”

We do, however, very much understand how they work. These toxins are designed to latch onto specific proteins embedded on the cell’s excitable membrane. This causes the cell’s ion channels to open, depolarizing the cell. After the affected cell exhausts the sodium at its immediate disposal, it stops transmitting electrical impulses. You only need picomolar (.001 mole) concentrations of these toxins in your system to begin feeling the effects.

“People who have been poisoned with this have had gastrointestinal problems, disorientation, dizziness, they describe their lips tingling,” Rein explained. There is also something called a temperature reversal sensation, where hot feels cold, and cold feels hot. You have to have a pretty high dose to get that, though.”

What’s worrisome is that many of these algae species (toxic or not) are spreading into formerly foreign environments and upsetting the local food web balance. Aureococcus anophagefferens, for example, used to only be found in the northeastern US and South Africa is now being pulled out of nuclear power plant cooling intakes in China. Aureoumbra lagunensis has spread from a single locale to expand along the entire Gulf Coast and recently migrated to Cuba. Most troubling is the spread of Ostreopsis, the toxic species thought to cause ciguatera fish poisoning. With a readily-aerosolable toxin, cases of respiratory distress have increased wherever Ostreopsis has flourished.

Frustratingly, researchers have yet to pin down why these blooms occur in the first place.

“We’ve tried and tried to look for the causes of red tide,” Richard Pierce, a senior scientist at Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, told National Geographic. “And it just seems to be something that likes the coast of Florida.”

Dinoflagellates like K. brevis exist in the ocean at concentrations of around 1,000 cells per liter of seawater. In fact natural algae blooms have occurred regularly throughout history (as British Columbia’s indigenous peoples can tell you), often when there is a seasonal upwelling of nutrients from the deep ocean or when a major storm or hurricane churns up the currents. This brings nitrogen- and phosphorus-rich waters to the surface where the algae can feast and reproduce. The natural balance can be upset by human activity near the coast, especially when nutrient-packed agricultural runoff reaches the sea to further feed the blooms.

Rising surface water temperatures resulting from climate change have also been linked to the blooms. Climate change may also play an indirect role in the formation of Red Tides by contributing to increasingly powerful hurricanes. That record-length 17-month Red Tide that bloomed between 2005 and 2006 was preceded by a pair of intense hurricane years off the coast of Florida. Those storms scoured the coastline, pouring nutrients into the local waters. Hurricane Irma in 2017 did the same in 2017 and is suspected as having helped cause this latest algae outbreak.

“The hurricane that went through there last year would have flushed huge amounts of nutrients into the coastal waters.,” Dr. Don Anderson, Senior Scientist in the Biology Department of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, explained to Engadget. “And then, that was months ago, but still some people are speculating that that would’ve been the hurricane effect. That it would have been just flushing the land out and washing all this nitrogen, phosphorus, and other things in to the coastal ocean, where it’s been available to fuel these kind of blooms.”

What’s more, this strengthening trend may have been going on since the 1950s. A 2008 study out of the University of Miami examined data on K. brevis from the past half century, finding that there were 13 to 18 times as many blooms in the 8 year span between 1994 and 2002 than there were between 1954 and 1963. The study’s authors blame increased human activity in Florida where nutrient-laden water from Lake Okeechobee (which is currently struggling with an algae bloom of its own) is diverted towards communities on the Gulf Coast. When the freshwater runoff comes into contact with seawater, “Those freshwater algae die, release all those nutrients, and that just feeds right into the [K. brevis] algae,” study author and University of Miami researcher Larry Brand wrote in the report.

Researchers from the Mote Lab are working on methods to minimize the effects of these blooms and mitigate the damage they cause to local ecosystems. One such device, which is currently in testing, injects ozone molecules into the water, destroying all organic compounds (including brevetoxins) present while aerating the fluid. The team has already completed small-scale testing using a 25,000 gallon tank and will soon attempt the experiment in a local 600,000-gallon canal.

While hosting the 2008 Olympics, the Chinese government took a decidedly low-tech approach towards minimizing the appearance of red tides: clay. “Uou disperse into the water, and the clay particles aggregate with each other, and with all the cells that are there, and they sink to the bottom,” Anderson explained. “And you can clear the water that way.”

Drones and autonomous underwater vehicles are also playing an increasingly large role in monitoring and modelling Red Tides. The “Brevebuster” AUV operated by the Mote Marine Lab, for example, is loaded with optical sensors which can identify the presence of K. brevis in the field based on the light absorbing characteristics of its collected water samples. Additionally the Imaging FlowCytobot from McLane Labs at the Woods Hole Oceanographic institute, incorporates an underwater flow cytometer to automatically photograph, count and even identify the kinds of cells that it collects in samples.

“Conscientious pursuit of goals for pollution reductions, including excess nutrients, could well prevent HABs in some locations,” Anderson wrote in his 2012 paper. “Careful assessment and precaution against species introductions via ballast water and aquaculture-related activities also can be effective preventative strategies.” However such strategies, he concedes, are more long-term solutions as it will take time for the excess nutrients in sediment are slowly flushed out.

Rein points to a number of other studies geared towards keeping red tides under control, including “using maybe a virus that’s specific for dinoflagellates, or seeding the bloom with another phytoplankton species that could out-compete K. brevis. Or even a parasitic dinoflagellate that infects other dinoflagellates.”

However, despite some studies initial successes, they’re not likely to be deployed in the near future. “Scientists are really, really wary of tinkering with the delicate ecological balance in the ocean,” she continued. “Because you start doing that, and you could end up with something worse.”

Even if we can’t beat back algae blooms any further than the tides themselves, perhaps we can at least exploit them. In 2004, researchers at the National Institute of Environmental Health Science in Florida were working to develop a defense against the irritating toxins produced by red tide algae. The researchers came up with a pair of “anti-toxins” — the manmade b-Naphthoyl-brevetoxin compound and brevenal, which is produced by the algae itself.

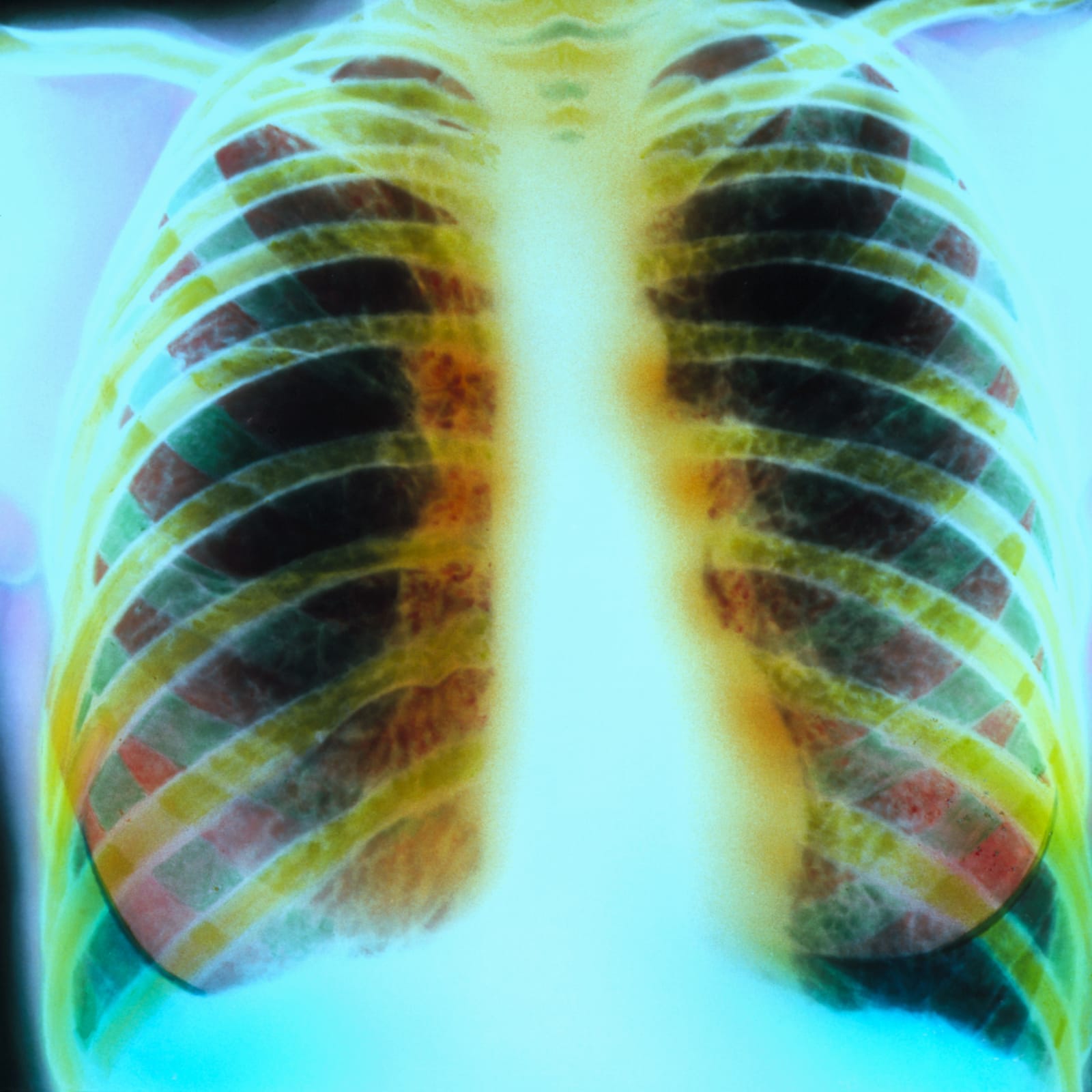

Not only did these anti-toxins prove to successfully mitigate irritating effects of getting aerosolized brevetoxin in the eye, nose and throat, the researchers also noticed that these compounds worked much in the same way as the current class of drugs used to treat cystic fibrosis — just far more effectively.

Cystic fibrosis is the most common fatal genetic disease for white people. An estimated 12 million people carry the defective gene and 30,000 actively suffer from the disease, which causes the lungs and airway to become clogged with thick mucus which serves as an idea breeding ground for bacteria.

“These compounds are excellent candidates for the development of an entirely new class of drugs targeted for the treatment of mucociliary disease,” Dr. Kenneth Olden, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, wrote in a statement at the time.

What’s more, they appear to be effective at doses magnitudes smaller — that is, you need a dose 1 million times lower — than what is currently required. “These agents can improve the clearance of mucus, and they may also work at concentrations that have no side effects,” Dr. William Abraham, pulmonary pharmacologist at Mount Sinai Medical Center and author of the study, said in the same statement.

These toxins are also being eyed for potential oncology applications as well. “One person’s toxin is the next person’s cancer drug,” Rein quipped.

No matter how we decide to tackle the red tide issue, we’re going to want to do it sooner than later. The Earth’s population is expected to hit 9 billion by the middle of the century and top 10 billion by the start of the next. With all those mouths to feed and thirsts to quench, humans will accelerate their exploitation of the planet’s shorelines while increasing the intensity of their agricultural efforts. Anderson estimates that we’ll need to boost food production by 30 percent by midcentury to keep up with humanity’s nutritional needs. That will be done, in the short term at least, through the liberal use of fertilizers, further complicating red tide mitigation efforts.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission