Omicron’s surging. What you need to know.

And what it means for 2022.

Abdul El-Sayed January 4, 2022

Let me start with the part you already know — probably from personal experience. Omicron is surging across the U.S.

We set several daily case records for new infections last week. Many of us watched friends and family — vaxxed and boosted — get infected, feeling as though the walls were closing in on us, too. “Name that infection” became the holidays’ most popular parlor game as we struggled to access rapid tests to know for sure whether our sniffles and scratchy throats were a common cold or something more sinister.

COVID has now infected nearly a sixth of all Americans. As omicron continues to surge, it’ll likely claim many more. And yet omicron is changing the nature of how we understand COVID. In November, I posed three questions that ought to guide our thinking about omicron. December brought us answers which may explain what we’re in for this January.

Omicron causes more breakthrough infections.

One question was whether omicron could better evade vaccine-mediated immunity. The answer is complicated: Vaccines were never intended to eliminate the risk of infection. Rather, they were tested against their ability to protect against serious symptoms among the infected. Nevertheless, the secondary benefit of protecting against infection in the first place emerged as a hallmark of vaccine messaging: that we should get vaccinated to protect ourselves and our communities.

What’s clear is that vaccinations continue to protect us from severe illness, particularly among those who are boosted. One analysis by the U.K. government of over a million people who were infected with either delta or omicron found that one dose alone was 52% effective at preventing hospitalization and two doses were 72% effective, although protection waned substantially after 25 weeks. Those who were boosted enjoyed 88% protection from hospitalization compared to the unvaccinated. Ultimately, the unvaccinated remain eight times as likely to be hospitalized from COVID.

The study also showed that booster doses were up to 75% effective at preventing infection within two to four weeks of having received the dose. But that protection waned to between 40-50% after 10 weeks. Protection from infection is more blunted, as the shocking number of breakthrough cases has demonstrated. In that respect, omicron is decidedly more vaccine evasive than previous variants.

To understand why omicron feels like it’s causing so many breakthrough cases, even among the boosted, remember that 25% of a skyrocketing number of exposures is still a lot of infections.

And that’s because …

Omicron is definitely more transmissible.

That much is certain. The vertical lines on graph after graph of COVID cases is all we need to answer that question. But the next question is more interesting: “Well, why?”

A flurry of research articles have all pointed to the same phenomenon. One study from the University of Liverpool’s Molecular Virology Research Group studied the pathophysiology of omicron in mice, and found that omicron was less likely to replicate in lung cells, opting for the cells of the throat instead. Another study from a group in Belgium found similar results in hamsters.

Replication in the throat — so close to the mouth and nose — could help explain, in part, why omicron is so transmissible. But it could also explain something else.

Omicron is less likely to require hospitalization (per individual).

Several studies have demonstrated that, indeed, each omicron case is less likely to require hospitalization. That U.K. study also showed us that, of 528,000 people infected with omicron and 573,000 people infected with delta, omicron-infected people were, at baseline, about a third as likely to require hospitalization.

That said, omicron could still paradoxically cause more hospitalizations. How? Because if there are more than three times the number of omicron cases as there are delta cases, even with a third the probability or hospitalizations, there could be more hospitalizations overall.

That complicates the way we understand “severity.” On an individual level, omicron is decidedly less severe. But on a population level, its transmissibility means that it could be more severe, causing substantially more pressure on our hospital system.

There’s another risk here. Omicron is already causing more hospitalization among young children, who for most of the pandemic have been spared the worst consequences of COVID-19. That’s in part because whereas the hospitalization rate for omicron among adults is lower, the hospitalization rate for omicron among children appears to be similar to that of delta. Multiply that by substantially more cases, and it helps explain why hospitalization among children is higher than it’s ever been.

The pathophysiology of omicron, which appears to replicate in the throat, may explain this. Pediatricians are reporting croup-like symptoms — a dry, barking cough — among patients who test positive for omicron. Because their necks are smaller, airway obstruction poses an acute risk for children, and may explain why a variant that disproportionately infects the upper airway could affect children so profoundly.

What does it mean for the state (and future) of the pandemic?

South Africa, where omicron was first discovered, has already reported that it’s beyond the peak of its omicron curve — and that it occurred without a spike in COVID mortality. What’s clear is that omicron moves fast. Infectious disease models suggest that we could hit the peak of our curve as early as next week, though most believe it’ll peak by the end of January.

In the interim, though, it’ll continue to wreak havoc. Though most cases are mild, its transmissibility has already caused disruptions across the economy — including the healthcare system and the airline industry. Over 2,000 flights were cancelled yesterday alone.

That’s, in part, what prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue new isolation guidelines for exposed and infected Americans, changing the individual isolation period from 10 days to only five. Though it’s generally true that omicron’s infection timeline appears to be shorter than previous variants, there’s no guarantee that infected people are not still not transmitting the virus after this new five-day period. Indeed, the guidelines should have required a negative test to assure that infected people weren’t spreading the extraordinarily transmissible variant after they isolated — a change the CDC is now considering.

That brings up the other challenge: there just isn’t enough testing to go around. Requiring tests would have accentuated our national testing shortage, rubbing in the egg that’s currently all over the Biden administration’s face on this. Ultimately, though, surging cases will do it just the same as people struggle to differentiate between COVID, the flu, and the common cold.

But there is a light at the end of this relatively short tunnel.

Omicron vs. delta vs. the next variant.

Right now, there’s a subcellular arms race raging between omicron and delta. Omicron’s winning: It’s more transmissible — and having had omicron seems to protect people from getting delta more than having had delta protects people from getting omicron. Immunity tends to wane with time. But because this surge is so broad and so quick, omicron is leaving a wall of acquired immunity in its wake.

Though the Great Wall of Immunity that omicron is currently constructing is no guarantee that the next variant may not drive right through it, it certainly makes it harder. In order to outcompete omicron, the next one will need to be different enough from omicron to evade omicron-mediated immunity, and/or to be yet more transmissible than it. That’s a big hurdle. Four serious variants in, I no longer put anything past SARS-CoV-2 … so I’m not saying that’s impossible. I’m just saying that once we’re finally there, omicron could potentially have played a role in getting us past the pandemic phase of COVID into the endemic phase.

What do we do now?

There’s a very difficult January ahead of us. Cases are likely to continue to skyrocket through the peak. We’re already near 500,000 cases per day, on average. A month of growth could spell tens of millions more cases.

First, if you haven’t yet boosted, I don’t know what you’re waiting for. There’s ample evidence that boosters protect against both infection and hospitalization with omicron. Get your booster now.

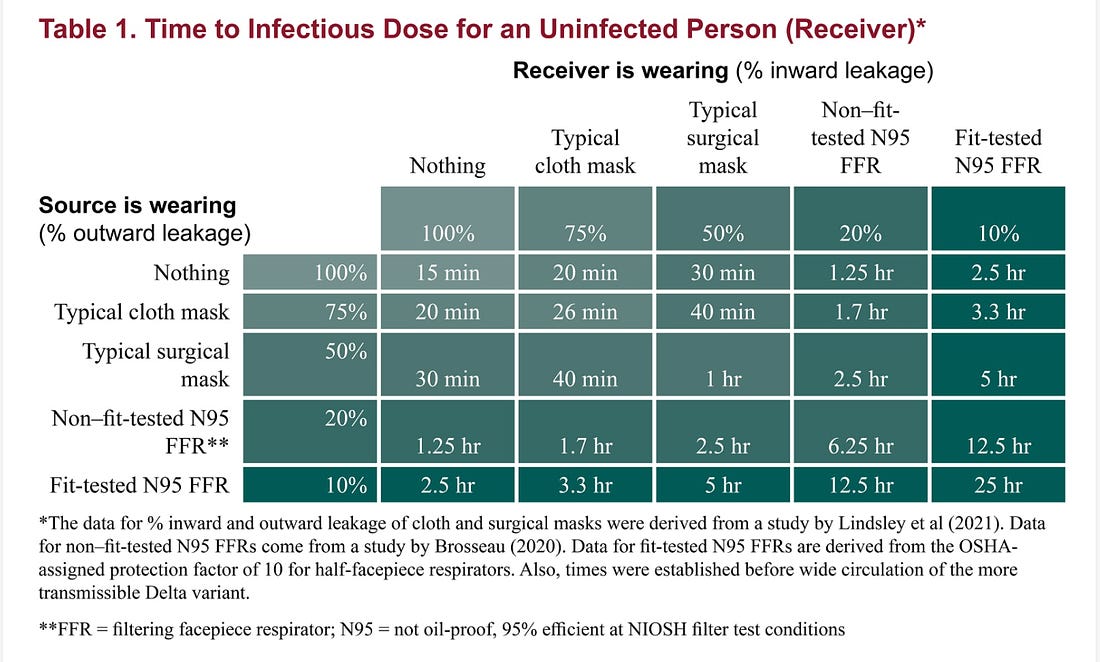

It’s also time to upgrade that fun cloth mask to something that’s medical grade. While any mask is better than no mask, medical grade masks are substantially better than cloth masks. The Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota estimates that an N95 can extend the amount of time it would take to breathe in an infectious dose of COVID if you were breathing the same air as an infected person fifty-fold, from 15 minutes to 12.5 hours — whereas the average cloth mask buys you about 5 minutes. And that was before omicron.

Rapid antigen tests are hard to come by; there’s also some question over how well they perform on omicron. But if you can get your hands on them, they can help provide some assurances for the most important social events.

Finally, January may be the month to forgo all but the most necessary social engagements. Remember, COVID doesn’t care how “over it” you are. It’s not yet over with us.