The Week

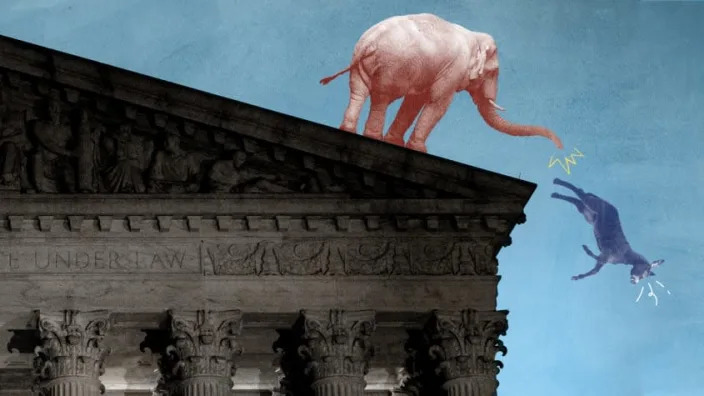

Could this SCOTUS case push America toward one-party rule?

Grayson Quay, Weekend editor – July 12, 2022

The Supreme Court has announced its intention to take up Moore v. Harper this fall, a case that critics claim is “perhaps the gravest threat to American democracy since the Jan. 6 attack.” Here’s everything you need to know:

What’s at stake in ‘Moore v. Harper’?

North Carolina House Speaker Timothy Moore (R) is suing a voter named Rebecca Harper as part of a dispute over a federal electoral map drawn by the state’s Republican-controlled legislature. According to The Carolina Journal, the case will test a legal theory known as the “independent state legislature doctrine,” which asserts that “only the state legislature has the power to regulate federal elections, without interference from state courts.”

Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution states that the “Times, Places, and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.” Proponents of the “independent state legislature doctrine” argue that this clause gives state legislatures the power to draw congressional districts, set rules for federal elections, and appoint presidential electors, and that state courts have no power to interfere — even if the legislature blatantly violates the state constitution.

Which, in this case, it totally did. The North Carolina Supreme Court ruled in February that the proposed map, which would have guaranteed Republicans easy wins in 10 of the state’s 14 districts, was “unconstitutional beyond a reasonable doubt under the … North Carolina Constitution.”

The situation in North Carolina is not so clear-cut, however. Robert Barnes noted in The Washington Post that the state’s General Assembly passed a law two decades ago empowering state courts to review electoral maps and even create their own “interim districting plan[s].” Moore’s lawyers must therefore prove that the legislature violated the U.S. Constitution by abdicating its own authority over redistricting.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the case in March but agreed on June 30 to hear it. Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh have all signaled their openness to Moore’s argument. The Washington Post‘s editorial board suggests that Chief Justice John Roberts — who three years ago left open the possibility that state courts could override partisan gerrymanders — is now “poised” to side with Moore as well. The board considers Justice Amy Coney Barrett “a possible swing vote.” All three of the court’s liberals are expected to reject the independent state legislature doctrine.

The case will be heard during the term beginning in October 2022, with a decision expected in the summer of 2023 — just in time to upend the 2024 elections.

What about the Electoral College?

In January, Ryan Cooper wrote for The Week that the state of Wisconsin “effectively exists under one-party rule.” Democrats can still win statewide elections — say, for governor or U.S. Senate — but state legislative districts are hopelessly gerrymandered in favor of Republicans. If the Supreme Court sides with Moore, GOP-controlled legislatures in states like Wisconsin would have full authority to rig not only their own states’ legislative elections, but elections to the U.S. House of Representatives as well.

And it might not stop there. Article II, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution empowers each state to “appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors” equal to that state’s number of senators and representatives. The clause doesn’t say anything about the popular vote. This means, in theory, that state legislators can appoint whoever they want to the Electoral College. If SCOTUS side with Moore next summer on the question of federal redistricting, they’re likely to apply the same reasoning to presidential elections. This interpretation was floated by conservative justices — including Thomas — during the Bush v. Gore (2000) case that handed George W. Bush the presidency.

The Electoral Count Act of 1887 stipulates that each state’s slate of electors must be certified by the governor of that state. In states like Wisconsin— which has a Democratic governor — this law could prevent the Republican-led legislature from handing the state’s electoral votes to a losing Republican candidate.

But wait — if the independent state legislature doctrine is correct, then the governor has no right to usurp the legislature’s constitutionally granted powers. That provision of the Electoral Count Act (ECA) would be struck down.

This idea “is quickly becoming dogma among Republican legal apparatchiks,” Cooper wrote. Convincing Republican-controlled states won by President Biden to submit alternate slates of Republican electors was a key part of Trump lawyer John Eastman’s strategy to overturn the 2020 presidential election. His plan also rested on the assumption that the ECA is “likely unconstitutional.”

What’s the worst-case scenario?

Zach Praiss of the nonprofit Accountable Tech and progressive talk show host Thom Hartmann have laid out similar nightmare scenarios that could arise if SCOTUS rules in Moore’s favor.

Hartmann imagines a 2024 presidential contest between Biden and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis in which Biden wins the popular vote in Georgia, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Arizona. The GOP-controlled legislatures of these six states then decide to disregard the will of the voters and award their 88 electoral votes to DeSantis, making him the winner and president-elect.

Republicans control both legislative houses in 29 states, plus the unicameral legislature of Nebraska, and they might soon gain the power to gerrymander themselves into a permanent majority. Those states control 306 electoral votes, more than enough to elect a president.

“It is difficult … to see the desire to put sole control of election rules in the hands of a partisan legislative body as anything more than a power grab,” argued Christine Adams in The Washington Post. Laurence H. Tribe and Dennis Aftergut were even blunter in the Los Angeles Times: “Adopting the independent state legislature theory would amount to right-wing justices making up law to create an outcome of one-party rule.”