The Guardian

Donald Trump-Paradise Papers

The wealthy men in Trump’s inner circle with links to tax havens

The president promised to bring trillions of dollars back to the US, but many around him are no strangers to the offshore world

Donald Trump: ‘Bring the money back. We’re rebuilding America.’ Photograph: AP, Guardian Design Team

Donald Trump: ‘Bring the money back. We’re rebuilding America.’ Photograph: AP, Guardian Design Team

Jon Swaine and Ed Pilkington, New York November 5, 2017

On the election trail in 2016, Donald Trump promised tax reforms to tempt major US companies back onshore and “bring back trillions of dollars from American businesses that is now parked overseas”.

As the first anniversary of his election victory looms this week, Trump and fellow Republicans are trying to drive those tax reforms through Congress.

On November 1st, Trump reiterated his commitment:

“Finally, our plan will bring back trillions of dollars from offshore … that will come pouring back into our country that will be put to work and will be spent by our companies that could never get the money back for many years. Bring the money back. We’re rebuilding America.”

But Trump is surrounded by wealthy individuals who have legally either sheltered their own investments or presided over policies to keep company profits or clients’ funds out of reach in tax havens.

Gary Cohn

Photograph: Kevin Dietsch/EPA

Photograph: Kevin Dietsch/EPA

Trump’s chief economic adviser, who is the driving force behind the White House tax reform effort, is no stranger to offshore finance. The leaked documents reveal that for various periods between 2002 and 2006, Cohn was president or vice-president of 22 separate entities in Bermuda for Goldman Sachs.

As head of the bank’s commodities and then equities divisions, Cohn spearheaded the bank’s purchase of companies from a financial arm of General Motors, GMAC Commercial Holding of Bermuda.

The Bermuda companies specialized in real estate, and though all were based on the island, they also had registered addresses at 85 Broad Street in New York City, the headquarters until 2009 of Goldman Sachs.

In 2012, the companies were struck from the Bermuda registry, a move that strips defunct or inactive companies from the records.

In a statement, Goldman Sachs said it did manage a fund that invested in Asia, but paid taxes on its income from the fund “in all relevant tax jurisdictions”. Of Cohn, the company said it was common for its employees to be officers of its legal entities and they were not paid for these additional roles.

Cohn, who did not respond to requests for comment, stood down from the Bermuda companies in 2006, around the time that he took up the position of president at Goldman Sachs.

Rex Tillerson

Photograph: Altaf Hussain/Reuters

Photograph: Altaf Hussain/Reuters

The US secretary of state is named in the leaked files as a director of an offshore firm used in a multi-billion dollar oil and gas venture in the Middle East that became embroiled in controversy.

Tillerson was a director of Marib Upstream Services Company, incorporated in Bermuda in 1997. The company was tied to ExxonMobil, the American oil and gas corporation that Tillerson later led as chief executive. At the time, Tillerson was president of ExxonMobil’s Yemen division.

ExxonMobil and Hunt Oil, another Texas-based firm led by Tillerson’s close friend Ray Hunt, ran a $5bn venture to export 61m barrels of natural gas a year from fields in Marib, western Yemen. Hunt had discovered the fields in the mid-1980s and brought in ExxonMobil to help develop them.

Yemen later moved to nationalize the gas-drilling operation, banishing the ExxonMobil, Hunt firm when its 20-year exploration contract expired in 2005. The Texans claimed they were entitled to an extension and sued Yemen for $1.6 billion. The case was arbitrated at the International Chamber of Commerce, where Yemen prevailed.

A report published last year by the campaign group Citizens for Tax Justice said ExxonMobil had at least 35 subsidiaries in tax havens such as the Bahamas, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands – and was holding approximately $51bn offshore while Tillerson was CEO.

A state department spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

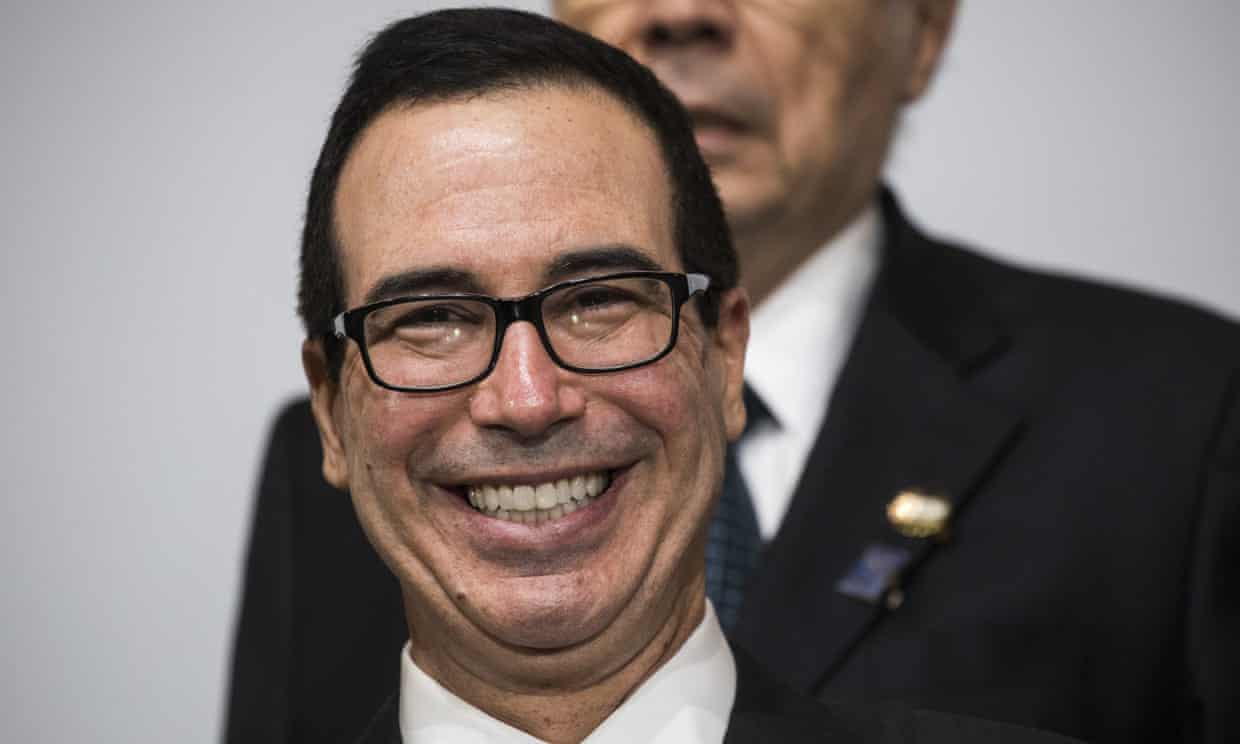

Steven Mnuchin

Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The US Treasury secretary’s former bank financed offshore private jets for wealthy clients, including a billionaire Yemeni businessman whose son is wanted for rape and murder in the UK.

CIT Bank, where Mnuchin was deputy chairman, provided customers with financing structures for personal aircraft priced at tens of millions of dollars, which customers used to legally avoid sales taxes and other charges.

One leaked file from October 2015 shows CIT billing an Isle of Man company $430,993 for an installment on a $30 million Dassault Falcon 2000EX jet. Other files say that the ultimate owner of the Isle of Man company is Shaher Abdulhak Besher.

Besher, an ally of the former Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh, has a business portfolio spanning drinks bottlers, telecoms and several other industries.

His son Farouk Abdulhak, 30, is wanted in London on suspicion of raping and murdering Martine Vik Magnussen, a 23-year-old student, who was found dead in a basement in Fitzrovia in May 2008. He denies the allegations.

Mnuchin is not named in the leaked documents and it is unclear whether he was aware of the arrangements. The financing for Besher was set up by CIT in 2012, before Mnuchin’s arrival. The arrangement continued through Mnuchin’s tenure. Mnuchin was paid $11.2m by CIT in 2016, before leaving to join Trump’s administration. CIT sold its aircraft financing division last year.

A spokeswoman for CIT said: “CIT complies with all laws, regulations and ethical standards in pursuit of its business.” An attorney for Besher said he declined to comment. Treasury spokespeople did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Randal Quarles

The Trump administration’s most senior banking watchdog appears in the Paradise Papers in connection with an offshore bank that is under investigation by US authorities for possible tax evasion.

Quarles, Trump’s vice-chairman for supervision at the Federal Reserve, is named in the files as an officer of two firms incorporated in the Cayman Islands by the Carlyle Group, the private equity giant where Quarles was a partner until 2013.

The files detail transactions between one of Quarles’s offshore vehicles and Butterfield, a Bermuda-based bank in which Carlyle had led a $550m investment in 2010. That stake was one of several in distressed banks bought up by a new specialist team at Carlyle, including Quarles, following the 2008 financial crisis.

In November 2013, federal authorities secured court orders requiring a group of US banks to disclose information on Americans “who may be evading or have evaded federal taxes” via undisclosed affiliated accounts at offshore banks including Butterfield. They said 81 such accounts at Butterfield had already been disclosed.

Butterfield said in its last annual report that it was cooperating with US authorities and had set aside $5.5m to pay penalties that may arise from the inquiries.

Quarles told ethics regulators this year that he held assets worth between $5m and $25m in a Carlyle fund that held a stake in Butterfield. He said he intended to sell his holdings in that and most other Carlyle funds.

A Federal Reserve spokesman said Quarles “had no specific responsibilities, was not delegated any responsibilities by the board, and received no income for this position” at the offshore company, and had divested from Butterfield when he joined the government.

Jon Huntsman

Photograph: Rick Bowmer/AP

Photograph: Rick Bowmer/AP

Trump’s new US ambassador to Russia helped lead a previously undisclosed offshore company, according to the leaked files.

Huntsman, the former Utah governor, was listed as a director of HICI International Sales Corporation in a confidential filing to authorities in Barbados, where the company was formed in 1999. The offshore vehicle was set up to carry out overseas sales for Huntsman ICI, an industrial chemicals branch of Huntsman Corporation.

The filing said HICI was owned by Huntsman ICI Holdings LLC in the US, where Huntsman was vice-chairman and manager. In 2000, Huntsman ICI reported making a $151m profit on revenues of $4.4bn.

HICI was a foreign sales corporation, a type that allowed Americans to exempt 32% of overseas income from US taxation under 1984 reforms signed by Ronald Reagan. The US closed the loophole in 2007.

Troy Keller, a spokesman for Huntsman Corporation, said of HICI: “It existed for just a few years and it participated in a US government-created program to promote exports.”

Huntsman Corporation did not report the offshore vehicle in its public filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Subsidiaries in tax havens may be omitted from public filings if they comprise less than 10% of a company’s assets, investments, or income.

The leaked files did not detail how much revenue passed through HICI. When he ran for president in 2012, Huntsman said his stakes in Huntsman companies were worth up to $50m.

Kenneth Juster

Trump’s ambassador to India benefited from the offshore business of his former investment company and its billion-dollar purchase of a shipping corporation.

Juster is named in the Paradise Papers as a beneficial owner of a Bermuda-based branch of Warburg Pincus, a private equity firm where he was a partner before joining the Trump administration.

Juster, who was a senior economic adviser to the president until this summer, declared holdings in Warburg Pincus worth up to $5m to ethics officials this year.

He was separately listed among Warburg partners in compliance documents relating to the buyout firm’s 2011 purchases of Triton Container International, a shipping container leasing company, and its sister firm International Asset Systems, which makes cargo tracking software.

A state department official said in an email: “Mr Juster has, at all times, fully disclosed and properly reported these financial interests on his US federal income tax returns. He also has timely filed and fully paid all US federal income tax liabilities in connection with the ownership of these interests.”

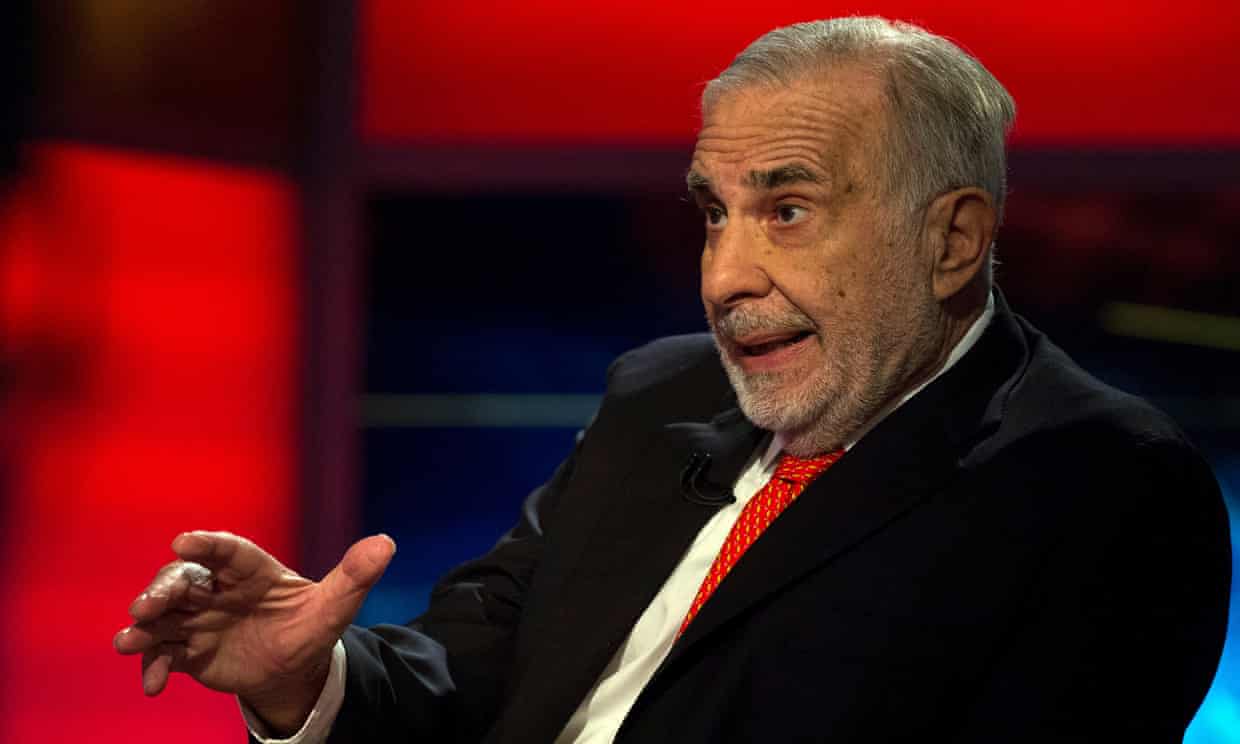

Carl Icahn

Photograph: Brendan Mcdermid/Reuters

Photograph: Brendan Mcdermid/Reuters

Icahn, a friend and former adviser to Trump, owns a $250m mining company spread across three tax havens and structured in a way that limits the information it must disclose to US authorities.

The leaks detail how Icahn holds a controlling stake in Ferrous Resources, a Brazilian mining company officially based on the Isle of Man. It in turn owns a pair of holding companies in Luxembourg and Malta, which operate iron mines in Brazil.

All three jurisdictions offer low- or zero-tax regimes for corporations, making them destinations of choice for foreign businesses seeking to legally lower their tax bills. A report in 2015 by Citizens for Tax Justice said Icahn operated 20 subsidiaries in offshore tax havens.

Icahn was a special adviser to the president until August and has a net worth of about $16.6bn, according to Forbes.

An email unearthed in the Paradise Papers said the structure of Ferrous Resources meant it escaped some disclosure requirements under an Obama-era law aimed at preventing offshore tax avoidance. The structure of Ferrous Resources was in place when Icahn bought the company.

Icahn was separately identified in the documents as having been a director for 11 years of Scientia Health Group, an investment company based in Bermuda in which he and his wife, Gail, held a stake. The firm’s investors also included the celebrity chef and lifestyle guru Martha Stewart and the disgraced film mogul Harvey Weinstein.

Jesse Lyn, general counsel for Icahn Enterprises, said: “We invested significant sums to save Ferrous from bankruptcy and to date have lost hundreds of millions of dollars on the investment.” Lyn said Icahn formerly held a small stake in Scientia which had “nothing to do with the company’s tax planning or structuring”.

Tom Barrack

Photograph: Bloomberg via Getty Images

Photograph: Bloomberg via Getty Images

The chairman of Trump’s inaugural committee leads a $58bn real estate investment trust that channels some of its profits to the low- or no-tax jurisdictions of Luxembourg, the Cayman Islands and Lebanon.

Barrack, who has described himself as one of the president’s “closest friends for 40 years”, appears in the Paradise Papers through offshore subsidiaries of Colony NorthStar, of which he is CEO.

In 2011, Appleby helped devise a rolling credit facility linking Barrack’s US-based investment funds with a pair of Cayman-Islands-based subsidiaries dealing in troubled real estate, which the lawyers asked him personally to approve.

A confidential chart in the leaked documents suggested money would flow from the funds in Delaware to a Cayman Islands entity, Colony Distressed Credit Fund II Feeder A, which was “exempted”, meaning it paid no local taxes. The chart suggested the money would then be repatriated in a complex web to a separate Delaware subsidiary closer to the parent company.

Barrack was an early endorser of Trump for president, co-founding the Rebuilding America Now Super Pac, which pumped $ 23 million into the 2016 race. He was rewarded by being invited to deliver a keynote address at the Republican national convention.

Barrack declined to clarify whether he was aware that Colony was passing money through a subsidiary in the Cayman Islands or whether the feeder funds were set up to reduce tax payments. The firm said: “Colony NorthStar is in strict compliance with the letter and spirit of all applicable rules for cross-border business, as we have been for more than 25 years.”

Jay Clayton

Trump’s SEC chairman received income from a hedge fund based in the Cayman Islands.

Clayton disclosed to the government ethics office before taking up the SEC job that he received income from Mount Kellett Capital Partners (Cayman) LP, the offshore subsidiary of a US hedge fund. A proposed structure chart in the leaked Appleby files shows a complex web of ties that were created between the Cayman Islands offshoot, its head company, and other offshore subsidiaries.

According to his ethics disclosure, Clayton received income from Mount Kellett through a trust set up for partners of Sullivan & Cromwell, the law firm where he worked for many years. In March, he agreed to divest from the fund within 90 days of taking up his SEC post.

Clayton declined to say how much he received annually from the Cayman Islands subsidiary, or to comment on how his involvement offshore would affect his new role as overseer of offshore investments.

As a corporate lawyer, Clayton gained a reputation for his close ties to Wall Street. As SEC chairman, his role is to protect investors and ensure the smooth working of the markets. Within that an important function is to keep an eye on the offshore interests of companies and hedge funds.

Trump has encouraged the SEC to eradicate many regulations. One of Clayton’s first moves was to allow private companies to be more secretive in the process of going public.

Ben Carson

Photograph: Carlo Allegri/Reuters

Photograph: Carlo Allegri/Reuters

A biotechnology company headed by Carson, Trump’s housing and urban development (HUD) secretary, set up offshore firms that could have reduced its tax bill.

The Paradise Papers contain files on two subsidiaries of Vaccinogen in Bermuda that date from Carson’s time as chairman of the Baltimore-based biotechnology company. The offshore vehicles were established as holding companies for “intellectual property related to the treatment of cancer and other diseases”, according to the files.

Offshore holding firms can be used to lower corporate tax bills for firms that make money from inventions or creative productions. Typically the offshore entity holds the intellectual property, leases it back to the parent company, and collects the royalties or revenues from its use. Tax havens such as Bermuda impose no tax on company profits. Vaccinogen did not respond to a request for comment.

The specific arrangements of Vaccinogen’s firms were not clear. One file named Michael A Bloom as a contact. An attorney with that name in New York states that he once “represented a publicly traded US pharmaceutical company in connection with IP tax migration and tax planning”. Bloom did not respond to an email.

Carson, a retired neurosurgeon, stood down as chairman of Vaccinogen in May 2015 after announcing that he was running for the Republican presidential nomination.

Raffi Williams, a spokesman for HUD, did not respond to several requests for comment. Williams eventually said questions should be directed to Carson’s personal attorney, and then declined to identify that attorney.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organizations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information. Thomasine F-R.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.