Esquire

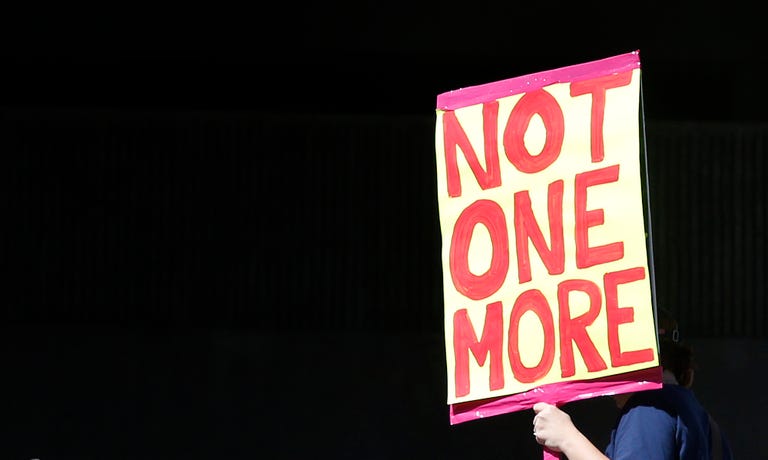

More Democrats Should Be Calling for the Repeal of the Second Amendment

They have to drag the middle of the conversation back to the middle.

By Jack Holmes March 27, 2018

Getty Images

Getty Images

No one in a national elected office advocates repealing the Second Amendment. No matter how many schoolchildren are cut down in a hail of bullets, no matter how many wives and girlfriends are shot to death by a spouse with a long history of abuse, no matter how many men commit suicide with a firearm in their own homes, the subject is never broached. No one in power is calling for government to restrict all gun ownership on that scale.

Occasionally, however, an outside observer will. Enter former Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, who called for repeal in a New York Times op-ed Tuesday:

“That support is a clear sign to lawmakers to enact legislation prohibiting civilian ownership of semiautomatic weapons, increasing the minimum age to buy a gun from 18 to 21 years old, and establishing more comprehensive background checks on all purchasers of firearms. But the demonstrators should seek more effective and more lasting reform. They should demand a repeal of the Second Amendment.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

This echoed the Times‘ conservative columnist Bret Stephens after the Las Vegas massacre in October:

“In fact, the more closely one looks at what passes for “common sense” gun laws, the more feckless they appear. Americans who claim to be outraged by gun crimes should want to do something more than tinker at the margins of a legal regime that most of the developed world rightly considers nuts. They should want to change it fundamentally and permanently.”

“There is only one way to do this: Repeal the Second Amendment.”

This was even floated by Karl Rove, the Republican operative who masterminded George W. Bush’s campaigns, after the massacre at Mother Emanuel church in Charleston:

“Now maybe there’s some magic law that will keep us from having more of these. I mean basically the only way to guarantee that we will dramatically reduce acts of violence involving guns is to basically remove guns from society, and until somebody gets enough “oomph” to repeal the Second Amendment, that’s not going to happen.”

For his part, Stevens—not Stephens—seems to think this would be a “simple” process:

“Overturning that decision via a constitutional amendment to get rid of the Second Amendment would be simple and would do more to weaken the N.R.A.’s ability to stymie legislative debate and block constructive gun control legislation than any other available option.”

This is a very legalistic take on things, befitting a judge. There is, indeed, a straightforward process to repealing an amendment—on paper. In reality, it is a Sisyphean political task. The last time a federal lawmaker introduced a bill to repeal the Second Amendment was in 1993, when Rep. Major Owens of New York brought one to the House. It went nowhere, just as it likely would now.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Even if Democrats regained control of both houses of Congress, the prospective amendment requires the approval of two-thirds of both houses. If it cleared that hurdle, it would need the approval of three-fourths of state legislatures. That doesn’t seem likely, even accounting for Stephens’—not Stevens’—slightly more realistic optimism:

“Repealing the Amendment may seem like political Mission Impossible today, but in the era of same-sex marriage it’s worth recalling that most great causes begin as improbable ones. Gun ownership should never be outlawed, just as it isn’t outlawed in Britain or Australia. But it doesn’t need a blanket Constitutional protection, either.”

All that said, there is political utility in staking out a position on the far end of the spectrum. Just ask Republicans. On gun rights alone, the NRA and its Republican lackeys have adopted the position that any restriction on gun ownership is unconstitutional and oppressive—and at the same time, that no gun restrictions will work, because criminals will still break the law.

(The latter, it bears repeating, is an argument against all laws. Laws are meant to construct obstacles to, and institute penalties for, bad behavior. The goal is to deter it, not prevent it from happening anywhere, ever. That someone robbed a bank is not evidence we should just give up on having laws against robbing banks. What if we tried passing better laws? As for the former, the Constitution specifically outlines how to amend it, meaning the Founders did not intend for it to be a sacred text that could never be changed. That’s why we’ve amended it 17 times since.)

Getty Images

Getty Images

That’s how Congress could not even pass a fix for federal background checks after a gunman with an AR-15-style rifle gunned down 20 six-year-olds in the halls of their elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut. The NRA dragged the conversation among gun-rights advocates so far to the extreme that even modest solutions became unacceptable. Lawmakers were then threatened with the wrath of this radicalized constituency, even if a huge majority of gun owners backed the background checks fix. The loudest, most radical voices won out.

On the flip side, Democrats have repeatedly shown why beginning a debate by staking out a position of compromise is political malpractice. When President Obama embarked on his quest to pass healthcare reform, he quickly abandoned any push for a universal healthcare system like Medicare for All. As the process moved along, he also scrapped plans for a “public option,” the next-best thing for liberals.

RELATED STORY

Share These Gun Violence Numbers with Anyone

What he presented to Republicans in Congress was already a compromise: the Affordable Care Act was modeled on Mitt Romney’s brainchild in Massachusetts, and sought to, in part, use market forces to bring down healthcare costs. By this point, Republicans had embraced an ethos of all-out power politics, so they called it socialism and said Obama wanted to kill your grandma with a Death Panel.

Obama narrowly succeeded without support from a single Republican. If he’d started out calling for Medicare for All, would Republicans have backed something like the ACA? And might the ultimate solution have been somewhere in between—like, say, a public option?

For the longest time, Democrats have called for incremental changes to our gun laws. They want to expand universal background checks, institute waiting periods, and, on the “extreme” end, ban semiautomatic weapons. This has gotten them exactly nowhere. What if there was a Freedom Caucus-like group in the Democratic Party—without the complete detachment from reality—that argued for outright repeal of the Second Amendment? As Stephens put it in his op-ed, repealing the Second Amendment doesn’t necessarily mean ending gun ownership.

There’s a strong argument that some Americans need to own a gun to defend themselves, whether they live in rural areas where it takes too long for police to respond or they are, say, a single woman living in a dangerous neighborhood. Hunting is ingrained in local culture in large swathes of America, and should be possible. The question is what guns should be permitted for these uses, and who should be permitted to have them. Common sense, and every other developed country in the world, would say a handgun or a hunting rifle—not an AR-15.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Repealing the Second Amendment would simply make it easier to pass restrictions on gun ownership, as Stephens suggests. It should be possible under the amendment—two of the first three words of it are “well regulated”—but constant legal action from the NRA and others has made that impossible. That culminated with the Supreme Court’s 2008 decision in Heller v. District of Columbia, which, in a bit of conservative judicial activism, essentially established the individual right to bear arms under the Second Amendment more than 200 years after its passage. Much like with Citizens United and the flood of corrupt, unaccountable money it has allowed into our politics, the Supreme Court has exacerbated a problem the rest of us must now solve.

Even if repeal is politically treacherous, there must be a constituency in the nation’s highest legislative body that backs it. It is probably the right thing to do, but at the very least, it pulls the conversation back from the cliff over which gun-rights extremists have all of our feet dangling. Amid calls for outright repeal, more Republicans might warm up to the idea that it shouldn’t be easier for an untrained civilian to get a weapon of war than to drive a car. And, when the grand compromise finally reaches the table, Democrats can get it across the line by allowing AR-15’s to be kept and used at gun ranges. That’s the Art of the Deal.