Detroit Free Press-USA Today

Chief justice: Pay no attention to the rigged election behind the curtain

Brian Dickerson, Detroit Free Press Columnist October 8, 2017

SCOTUS is lined up to hear cases on topics like labor relations, gerrymandering and voters’ rights. Video available by Newsy Newslook

(Photo: Olivier Douliery, Getty Images)

(Photo: Olivier Douliery, Getty Images)

For 12 years, Chief Justice John Roberts has worked overtime peddling the dubious conceit that he and his life-tenured colleagues on the U.S. Supreme Court are above politics and determined to remain so.

Yet Roberts himself is a consummate politician — a strategist who worries about appearances and harbors a ward heeler’s contempt for the intelligence of the average voter. And his cynicism was on full display last week when justices took up the politically fraught problem of gerrymandering.

Plaintiffs in a case known as Gill v. Whitford want the Supreme Court to rule that Wisconsin legislators violated the U.S. Constitution when they drew district boundaries that systematically diluted the electoral clout of their state’s Democratic voters.

Dickerson: Has Justice Kennedy finally had enough of partisan gerrymandering?

More: State panel approves petition aimed at ending gerrymandering

A lower court ordered Wisconsin to draw a fairer map after concluding that evidence and voting data submitted by the plaintiffs proved Republicans had configured districts designed to preserve their party’s legislative majority even when Democrats win a majority of the popular vote.

Roberts, who knows a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs will jeopardize Republican gerrymanders in more than a dozen other states, wants his colleagues to stay out of a partisan process even simpatico conservatives like Justice Samuel Alito concede is “distasteful.” The chief justice says the public will lose respect for the courts if he and his colleagues stick their noses into all that distastefulness.

Buy Photo

Buy Photo

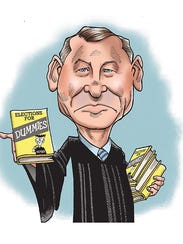

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts says voters would think the high court was throwing elections for Democrats if tried to put a stop to gerrymandering. (Photo: Mike Thompson/Detroit Free Press)

But what if a majority party uses its mapmaking prowess to effectively disenfranchise the opposing party’s voters? And what if those aggrieved voters can use the same technological advances their opponents exploited to prove an election was rigged, and even to quantify the advantage its rivals gained by manipulating a state’s political boundaries?

That’s exactly what has happened in the Wisconsin case, as one of the country’s premier scientists explained in a remarkable friend-of-the-court brief filed on behalf of the plaintiffs.

Mapping chromosomes and rigged elections

It’s rare for disinterested third parties to play a decisive role in landmark Supreme Court cases. But the arguments filed by Eric Lander, a geneticist and mathematician who oversees the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, may prove an exception.

Lander was one of the principal leaders of the decade-long effort to map the human genome, and he has advised the White House and the Pentagon on innovative uses of technology for national defense. In a brief that several justices cited during Tuesday’s oral arguments, Lander says the sort of data-crunching the federal government uses to assess whether a nuclear weapon will detonate properly or whether Miami is safely outside the path of a hurricane can be used to prove when political boundaries have been manipulated to guarantee one party the largest possible electoral advantage.

Lander’s argument is a crucial one, because lawsuits challenging the fairness of gerrymandered political districts have foundered on the high court’s doubts that challengers could propose an objective standard for evaluating partisan bias.

Lander says technological advances that allow mapmakers to project likely electoral outcomes in thousands of different scenarios mean that a party that controls the redistricting process can pick the map that yields the most extreme partisan advantage. But he adds that the same analytical methods allow courts to discover when district lines have been manipulated to produce the maximum distortion of the electorate’s will, whether by amplifying the impact of one party’s voters or minimizing its opponents’ ability to muster an electoral majority in most districts.

By comparing the district lines a state has adopted with all the other possible configurations that comply with state and federal law, courts can determine not only whether a given map handicaps one party’s voters, but also how much. Using these reliable analytical tools, Lander says, deciding which of several possible maps yields electoral outcomes most consistent with the majority’s druthers becomes “a mathematical question to which there is a right answer” — exactly the sort of objective test judges worried about the corrosive effects of gerrymandering have been seeking.

Gobbledygook?

Chief Justice Roberts, of course, doesn’t see it that way. During oral arguments last week, he dismissed the evidence Lander and other mathematical analysts have submitted as proof Wisconsin’s legislative elections are rigged as “sociological gobbledygook.”

In another exchange with the plaintiffs’ attorneys, the chief justice appeared to concede that the evidence he disparaged might be persuasive after all, once you took the time to digest it, but hinted that few voters had the patience or smarts to do so.

“The intelligent man on the street is going to say that’s a bunch of baloney,” Roberts insisted. If justices blow the whistle on Republican cheating, he believes, the public will inevitably conclude that they’re simply shilling for Democrats — “And that is going to cause very serious harm to the status and the integrity of the decisions of this Court in the eyes of the country.”

Roberts’ argument amounts to a rejection of rational inquiry itself: If the evidence that Wisconsin has violated its citizens’ constitutional rights is too sophisticated for laymen to grasp at first glance, he says, the court would be better off to ignore it.

This is the same cynically anti-intellectual rationale cheerleaders for the fossil fuel industry have marshaled to discredit the evidence of climate change. Until “the intelligent man on the street” has a keener understanding of the role greenhouse gases play in global warming, why should elected officials kowtow to experts who do?

Of course, the same logic could be marshaled to discount the warnings of hurricane forecasters or military strategists trying to anticipate the likely consequences of a military confrontation in the Middle East or on the Korean peninsula. If we don’t understand their calculations, why should we pay any attention to them?

The answer, of course, is that democratic government, like many other aspects of daily life, requires a reasonable deference to those with superior expertise: the surgeon who does hundreds of bypass operations a year, the repair technician who diagnoses malfunctioning furnaces for a living, or the pilot with 10,000 hours of in-flight service under her belt.

Roberts is right to be worried about the credibility of the judiciary, and its capacity to command the confidence of citizens across the political spectrum. But he should be at least as concerned about the credibility of representative democracy itself.

As Paul Smith, who represents the plaintiffs challenging Wisconsin’s legislative map argues, the stakes in Gill v. Whitford are larger than the public’s perception of Justice Roberts and his colleagues.

“If you let this go, if you say … we’re not going to have a judicial remedy for this problem, in 2020 you’re going to have a festival of copycat gerrymandering the likes of which this country has never seen,” Smith warned Roberts near the end of Tuesday’s oral arguments. “Voters everywhere are going to be like voters in Wisconsin, and (say): No, it really doesn’t matter whether I vote.”

Contact Brian Dickerson: bdickerson@freepress.com