TIME

How Far Trump Would Go

By Eric Cortellessa, Palm Beach FLA. – April 30 2024

Donald Trump thinks he’s identified a crucial mistake of his first term: He was too nice.

We’ve been talking for more than an hour on April 12 at his fever-dream palace in Palm Beach. Aides lurk around the perimeter of a gilded dining room overlooking the manicured lawn. When one nudges me to wrap up the interview, I bring up the many former Cabinet officials who refuse to endorse Trump this time. Some have publicly warned that he poses a danger to the Republic. Why should voters trust you, I ask, when some of the people who observed you most closely do not?

As always, Trump punches back, denigrating his former top advisers. But beneath the typical torrent of invective, there is a larger lesson he has taken away. “I let them quit because I have a heart. I don’t want to embarrass anybody,” Trump says. “I don’t think I’ll do that again. From now on, I’ll fire.”

Six months from the 2024 presidential election, Trump is better positioned to win the White House than at any point in either of his previous campaigns. He leads Joe Biden by slim margins in most polls, including in several of the seven swing states likely to determine the outcome. But I had not come to ask about the election, the disgrace that followed the last one, or how he has become the first former—and perhaps future—American President to face a criminal trial. I wanted to know what Trump would do if he wins a second term, to hear his vision for the nation, in his own words.

What emerged in two interviews with Trump, and conversations with more than a dozen of his closest advisers and confidants, were the outlines of an imperial presidency that would reshape America and its role in the world. To carry out a deportation operation designed to remove more than 11 million people from the country, Trump told me, he would be willing to build migrant detention camps and deploy the U.S. military, both at the border and inland. He would let red states monitor women’s pregnancies and prosecute those who violate abortion bans. He would, at his personal discretion, withhold funds appropriated by Congress, according to top advisers. He would be willing to fire a U.S. Attorney who doesn’t carry out his order to prosecute someone, breaking with a tradition of independent law enforcement that dates from America’s founding. He is weighing pardons for every one of his supporters accused of attacking the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, more than 800 of whom have pleaded guilty or been convicted by a jury. He might not come to the aid of an attacked ally in Europe or Asia if he felt that country wasn’t paying enough for its own defense. He would gut the U.S. civil service, deploy the National Guard to American cities as he sees fit, close the White House pandemic-preparedness office, and staff his Administration with acolytes who back his false assertion that the 2020 election was stolen.

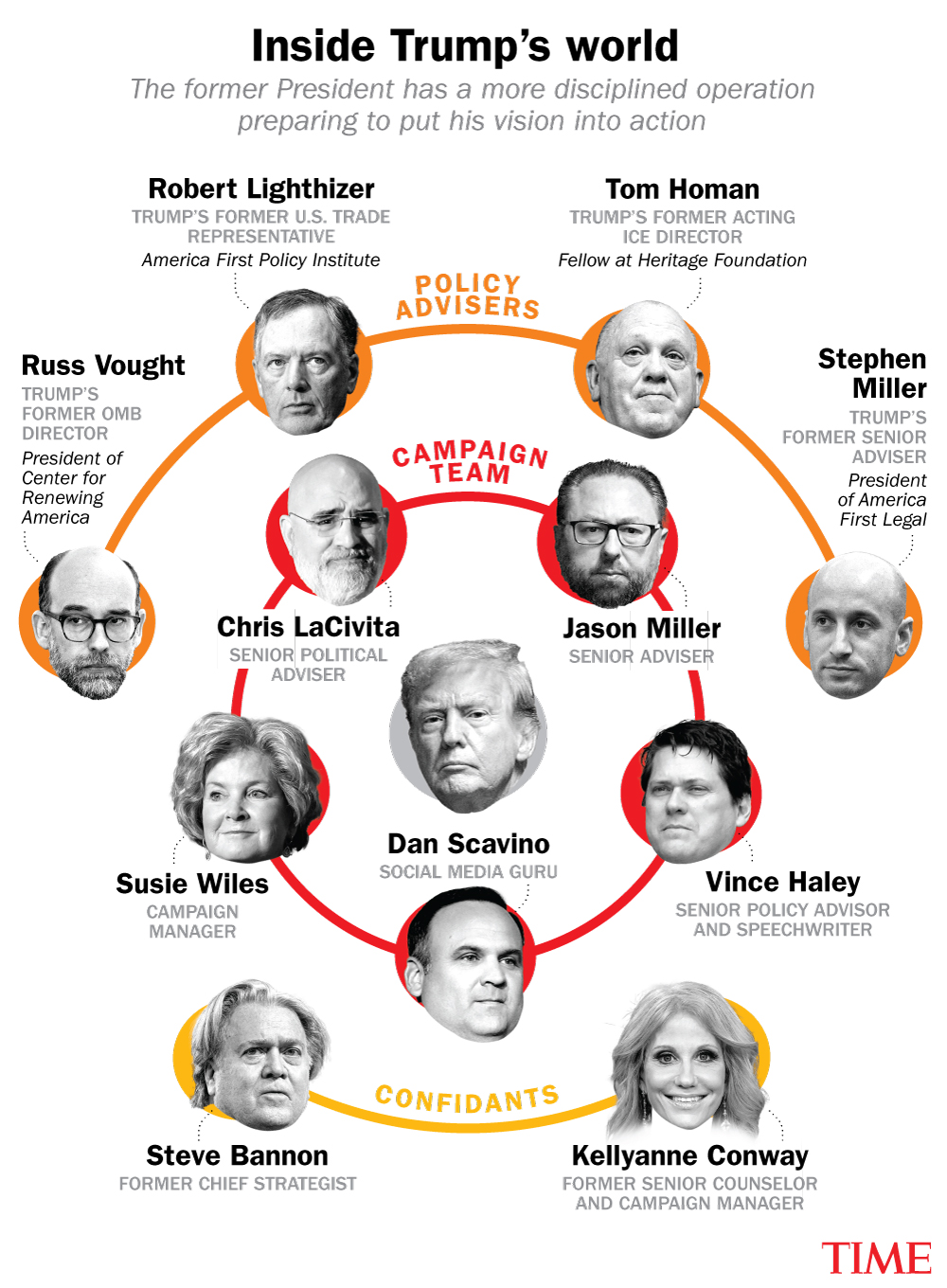

Trump remains the same guy, with the same goals and grievances. But in person, if anything, he appears more assertive and confident. “When I first got to Washington, I knew very few people,” he says. “I had to rely on people.” Now he is in charge. The arranged marriage with the timorous Republican Party stalwarts is over; the old guard is vanquished, and the people who remain are his people. Trump would enter a second term backed by a slew of policy shops staffed by loyalists who have drawn up detailed plans in service of his agenda, which would concentrate the powers of the state in the hands of a man whose appetite for power appears all but insatiable. “I don’t think it’s a big mystery what his agenda would be,” says his close adviser Kellyanne Conway. “But I think people will be surprised at the alacrity with which he will take action.”

Read More: Read the Full Transcripts of Donald Trump’s Interviews With TIME

The courts, the Constitution, and a Congress of unknown composition would all have a say in whether Trump’s objectives come to pass. The machinery of Washington has a range of defenses: leaks to a free press, whistle-blower protections, the oversight of inspectors general. The same deficiencies of temperament and judgment that hindered him in the past remain present. If he wins, Trump would be a lame duck—contrary to the suggestions of some supporters, he tells TIME he would not seek to overturn or ignore the Constitution’s prohibition on a third term. Public opinion would also be a powerful check. Amid a popular outcry, Trump was forced to scale back some of his most draconian first-term initiatives, including the policy of separating migrant families. As George Orwell wrote in 1945, the ability of governments to carry out their designs “depends on the general temper in the country.”

Every election is billed as a national turning point. This time that rings true. To supporters, the prospect of Trump 2.0, unconstrained and backed by a disciplined movement of true believers, offers revolutionary promise. To much of the rest of the nation and the world, it represents an alarming risk. A second Trump term could bring “the end of our democracy,” says presidential historian Douglas Brinkley, “and the birth of a new kind of authoritarian presidential order.”

Trump steps onto the patio at Mar-a-Lago near dusk. The well-heeled crowd eating Wagyu steaks and grilled branzino pauses to applaud as he takes his seat. On this gorgeous evening, the club is a MAGA mecca. Billionaire donor Steve Wynn is here. So is Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, who is dining with the former President after a joint press conference proposing legislation to prevent noncitizens from voting. Their voting in federal elections is already illegal, and extremely rare, but remains a Trumpian fixation that the embattled Speaker appeared happy to co-sign in exchange for the political cover that standing with Trump provides.

At the moment, though, Trump’s attention is elsewhere. With an index finger, he swipes through an iPad on the table to curate the restaurant’s soundtrack. The playlist veers from Sinead O’Connor to James Brown to The Phantom of the Opera. And there’s a uniquely Trump choice: a rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” sung by a choir of defendants imprisoned for attacking the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, interspersed with a recording of Trump reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. This has become a staple of his rallies, converting the ultimate symbol of national unity into a weapon of factional devotion.

The spectacle picks up where his first term left off. The events of Jan. 6, during which a pro-Trump mob attacked the center of American democracy in an effort to subvert the peaceful transfer of power, was a profound stain on his legacy. Trump has sought to recast an insurrectionist riot as an act of patriotism. “I call them the J-6 patriots,” he says. When I ask whether he would consider pardoning every one of them, he says, “Yes, absolutely.” As Trump faces dozens of felony charges, including for election interference, conspiracy to defraud the United States, willful retention of national-security secrets, and falsifying business records to conceal hush-money payments, he has tried to turn legal peril into a badge of honor.

In a second term, Trump’s influence on American democracy would extend far beyond pardoning powers. Allies are laying the groundwork to restructure the presidency in line with a doctrine called the unitary executive theory, which holds that many of the constraints imposed on the White House by legislators and the courts should be swept away in favor of a more powerful Commander in Chief.

Read More: Fact-Checking What Donald Trump Said In His Interviews With TIME

Nowhere would that power be more momentous than at the Department of Justice. Since the nation’s earliest days, Presidents have generally kept a respectful distance from Senate-confirmed law-enforcement officials to avoid exploiting for personal ends their enormous ability to curtail Americans’ freedoms. But Trump, burned in his first term by multiple investigations directed by his own appointees, is ever more vocal about imposing his will directly on the department and its far-flung investigators and prosecutors.

In our Mar-a-Lago interview, Trump says he might fire U.S. Attorneys who refuse his orders to prosecute someone: “It would depend on the situation.” He’s told supporters he would seek retribution against his enemies in a second term. Would that include Fani Willis, the Atlanta-area district attorney who charged him with election interference, or Alvin Bragg, the Manhattan DA in the Stormy Daniels case, who Trump has previously said should be prosecuted? Trump demurs but offers no promises. “No, I don’t want to do that,” he says, before adding, “We’re gonna look at a lot of things. What they’ve done is a terrible thing.”

Trump has also vowed to appoint a “real special prosecutor” to go after Biden. “I wouldn’t want to hurt Biden,” he tells me. “I have too much respect for the office.” Seconds later, though, he suggests Biden’s fate may be tied to an upcoming Supreme Court ruling on whether Presidents can face criminal prosecution for acts committed in office. “If they said that a President doesn’t get immunity,” says Trump, “then Biden, I am sure, will be prosecuted for all of his crimes.” (Biden has not been charged with any, and a House Republican effort to impeach him has failed to unearth evidence of any crimes or misdemeanors, high or low.)

Read More: Trump Says ‘Anti-White Feeling’ Is a Problem in the U.S.

Such moves would be potentially catastrophic for the credibility of American law enforcement, scholars and former Justice Department leaders from both parties say. “If he ordered an improper prosecution, I would expect any respectable U.S. Attorney to say no,” says Michael McConnell, a former U.S. appellate judge appointed by President George W. Bush. “If the President fired the U.S. Attorney, it would be an enormous firestorm.” McConnell, now a Stanford law professor, says the dismissal could have a cascading effect similar to the Saturday Night Massacre, when President Richard Nixon ordered top DOJ officials to remove the special counsel investigating Watergate. Presidents have the constitutional right to fire U.S. Attorneys, and typically replace their predecessors’ appointees upon taking office. But discharging one specifically for refusing a President’s order would be all but unprecedented.

Trump’s radical designs for presidential power would be felt throughout the country. A main focus is the southern border. Trump says he plans to sign orders to reinstall many of the same policies from his first term, such as the Remain in Mexico program, which requires that non-Mexican asylum seekers be sent south of the border until their court dates, and Title 42, which allows border officials to expel migrants without letting them apply for asylum. Advisers say he plans to cite record border crossings and fentanyl- and child-trafficking as justification for reimposing the emergency measures. He would direct federal funding to resume construction of the border wall, likely by allocating money from the military budget without congressional approval. The capstone of this program, advisers say, would be a massive deportation operation that would target millions of people. Trump made similar pledges in his first term, but says he plans to be more aggressive in a second. “People need to be deported,” says Tom Homan, a top Trump adviser and former acting head of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “No one should be off the table.”

Read More: The Story Behind TIME’s ‘If He Wins’ Trump Cover

For an operation of that scale, Trump says he would rely mostly on the National Guard to round up and remove undocumented migrants throughout the country. “If they weren’t able to, then I’d use [other parts of] the military,” he says. When I ask if that means he would override the Posse Comitatus Act—an 1878 law that prohibits the use of military force on civilians—Trump seems unmoved by the weight of the statute. “Well, these aren’t civilians,” he says. “These are people that aren’t legally in our country.” He would also seek help from local police and says he would deny funding for jurisdictions that decline to adopt his policies. “There’s a possibility that some won’t want to participate,” Trump says, “and they won’t partake in the riches.”

As President, Trump nominated three Supreme Court Justices who voted to overturn Roe v. Wade, and he claims credit for his role in ending a constitutional right to an abortion. At the same time, he has sought to defuse a potent campaign issue for the Democrats by saying he wouldn’t sign a federal ban. In our interview at Mar-a-Lago, he declines to commit to vetoing any additional federal restrictions if they came to his desk. More than 20 states now have full or partial abortion bans, and Trump says those policies should be left to the states to do what they want, including monitoring women’s pregnancies. “I think they might do that,” he says. When I ask whether he would be comfortable with states prosecuting women for having abortions beyond the point the laws permit, he says, “It’s irrelevant whether I’m comfortable or not. It’s totally irrelevant, because the states are going to make those decisions.” President Biden has said he would fight state anti-abortion measures in court and with regulation.

Trump’s allies don’t plan to be passive on abortion if he returns to power. The Heritage Foundation has called for enforcement of a 19th century statute that would outlaw the mailing of abortion pills. The Republican Study Committee (RSC), which includes more than 80% of the House GOP conference, included in its 2025 budget proposal the Life at Conception Act, which says the right to life extends to “the moment of fertilization.” I ask Trump if he would veto that bill if it came to his desk. “I don’t have to do anything about vetoes,” Trump says, “because we now have it back in the states.”

Presidents typically have a narrow window to pass major legislation. Trump’s team is eyeing two bills to kick off a second term: a border-security and immigration package, and an extension of his 2017 tax cuts. Many of the latter’s provisions expire early in 2025: the tax cuts on individual income brackets, 100% business expensing, the doubling of the estate-tax deduction. Trump is planning to intensify his protectionist agenda, telling me he’s considering a tariff of more than 10% on all imports, and perhaps even a 100% tariff on some Chinese goods. Trump says the tariffs will liberate the U.S. economy from being at the mercy of foreign manufacturing and spur an industrial renaissance in the U.S. When I point out that independent analysts estimate Trump’s first term tariffs on thousands of products, including steel and aluminum, solar panels, and washing machines, may have cost the U.S. $316 billion and more than 300,000 jobs, by one account, he dismisses these experts out of hand. His advisers argue that the average yearly inflation rate in his first term—under 2%—is evidence that his tariffs won’t raise prices.

Since leaving office, Trump has tried to engineer a caucus of the compliant, clearing primary fields in Senate and House races. His hope is that GOP majorities replete with MAGA diehards could rubber-stamp his legislative agenda and nominees. Representative Jim Banks of Indiana, a former RSC chairman and the GOP nominee for the state’s open Senate seat, recalls an August 2022 RSC planning meeting with Trump at his residence in Bedminster, N.J. As the group arrived, Banks recalls, news broke that Mar-a-Lago had been raided by the FBI. Banks was sure the meeting would be canceled. Moments later, Trump walked through the doors, defiant and pledging to run again. “I need allies there when I’m elected,” Banks recalls Trump saying. The difference in a second Trump term, Banks says now, “is he’s going to have the backup in Congress that he didn’t have before.”

Trump’s intention to remake America’s relations abroad may be just as consequential. Since its founding, the U.S. has sought to build and sustain alliances based on the shared values of political and economic freedom. Trump takes a much more transactional approach to international relations than his predecessors, expressing disdain for what he views as free-riding friends and appreciation for authoritarian leaders like President Xi Jinping of China, Prime Minister Viktor Orban of Hungary, or former President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil.

That’s one reason America’s traditional allies were horrified when Trump recently said at a campaign rally that Russia could “do whatever the hell they want” to a NATO country he believes doesn’t spend enough on collective defense. That wasn’t idle bluster, Trump tells me. “If you’re not going to pay, then you’re on your own,” he says. Trump has long said the alliance is ripping the U.S. off. Former NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg credited Trump’s first-term threat to pull out of the alliance with spurring other members to add more than $100 billion to their defense budgets.

But an insecure NATO is as likely to accrue to Russia’s benefit as it is to America’s. President Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine looks to many in Europe and the U.S. like a test of his broader vision to reconstruct the Soviet empire. Under Biden and a bipartisan Congress, the U.S. has sent more than $100 billion to Ukraine to defend itself. It’s unlikely Trump would extend the same support to Kyiv. After Orban visited Mar-a-Lago in March, he said Trump “wouldn’t give a penny” to Ukraine. “I wouldn’t give unless Europe starts equalizing,” Trump hedges in our interview. “If Europe is not going to pay, why should we pay? They’re much more greatly affected. We have an ocean in between us. They don’t.” (E.U. nations have given more than $100 billion in aid to Ukraine as well.)

Read More: Read the Full Transcripts of Donald Trump’s Interviews With TIME

Trump has historically been reluctant to criticize or confront Putin. He sided with the Russian autocrat over his own intelligence community when it asserted that Russia interfered in the 2016 election. Even now, Trump uses Putin as a foil for his own political purposes. When I asked Trump why he has not called for the release of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, who has been unjustly held on spurious charges in a Moscow prison for a year, Trump says, “I guess because I have so many other things I’m working on.” Gershkovich should be freed, he adds, but he doubts it will happen before the election. “The reporter should be released and he will be released,” Trump tells me. “I don’t know if he’s going to be released under Biden. I would get him released.”

America’s Asian allies, like its European ones, may be on their own under Trump. Taiwan’s Foreign Minister recently said aid to Ukraine was critical in deterring Xi from invading the island. Communist China’s leaders “have to understand that things like that can’t come easy,” Trump says, but he declines to say whether he would come to Taiwan’s defense.

Trump is less cryptic on current U.S. troop deployments in Asia. If South Korea doesn’t pay more to support U.S. troops there to deter Kim Jong Un’s increasingly belligerent regime to the north, Trump suggests the U.S. could withdraw its forces. “We have 40,000 troops that are in a precarious position,” he tells TIME. (The number is actually 28,500.) “Which doesn’t make any sense. Why would we defend somebody? And we’re talking about a very wealthy country.”

Transactional isolationism may be the main strain of Trump’s foreign policy, but there are limits. Trump says he would join Israel’s side in a confrontation with Iran. “If they attack Israel, yes, we would be there,” he tells me. He says he has come around to the now widespread belief in Israel that a Palestinian state existing side by side in peace is increasingly unlikely. “There was a time when I thought two-state could work,” he says. “Now I think two-state is going to be very, very tough.”

Yet even his support for Israel is not absolute. He’s criticized Israel’s handling of its war against Hamas, which has killed more than 30,000 Palestinians in Gaza, and has called for the nation to “get it over with.” When I ask whether he would consider withholding U.S. military aid to Israel to push it toward winding down the war, he doesn’t say yes, but he doesn’t rule it out, either. He is sharply critical of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, once a close ally. “I had a bad experience with Bibi,” Trump says. In his telling, a January 2020 U.S. operation to assassinate a top Iranian general was supposed to be a joint attack until Netanyahu backed out at the last moment. “That was something I never forgot,” he says. He blames Netanyahu for failing to prevent the Oct. 7 attack, when Hamas militants infiltrated southern Israel and killed nearly 1,200 people amid acts of brutality including burning entire families alive and raping women and girls. “It happened on his watch,” Trump says.

On the second day of Trump’s New York trial on April 17, I stand behind the packed counter of the Sanaa Convenience Store on 139th Street and Broadway, waiting for Trump to drop in for a postcourt campaign stop. He chose the bodega for its history. In 2022, one of the store’s clerks fatally stabbed a customer who attacked him. Bragg, the Manhattan DA, charged the clerk with second-degree murder. (The charges were later dropped amid public outrage over video footage that appeared to show the clerk acting in self-defense.) A baseball bat behind the counter alludes to lingering security concerns. When Trump arrives, he asks the store’s co-owner, Maad Ahmed, a Yemeni immigrant, about safety. “You should be allowed to have a gun,” Trump tells Ahmed. “If you had a gun, you’d never get robbed.”

On the campaign trail, Trump uses crime as a cudgel, painting urban America as a savage hell-scape even though violent crime has declined in recent years, with homicides sinking 6% in 2022 and 13% in 2023, according to the FBI. When I point this out, Trump tells me he thinks the data, which is collected by state and local police departments, is rigged. “It’s a lie,” he says. He has pledged to send the National Guard into cities struggling with crime in a second term—possibly without the request of governors—and plans to approve Justice Department grants only to cities that adopt his preferred policing methods like stop-and-frisk.

To critics, Trump’s preoccupation with crime is a racial dog whistle. In polls, large numbers of his supporters have expressed the view that antiwhite racism now represents a greater problem in the U.S. than the systemic racism that has long afflicted Black Americans. When I ask if he agrees, Trump does not dispute this position. “There is a definite antiwhite feeling in the country,” he tells TIME, “and that can’t be allowed either.” In a second term, advisers say, a Trump Administration would rescind Biden’s Executive Orders designed to boost diversity and racial equity.

Trump’s ability to campaign for the White House in the midst of an unprecedented criminal trial is the product of a more professional campaign operation that has avoided the infighting that plagued past versions. “He has a very disciplined team around him,” says Representative Elise Stefanik of New York. “That is an indicator of how disciplined and focused a second term will be.” That control now extends to the party writ large. In 2016, the GOP establishment, having failed to derail Trump’s campaign, surrounded him with staff who sought to temper him. Today the party’s permanent class have either devoted themselves to the gospel of MAGA or given up. Trump has cleaned house at the Republican National Committee, installing handpicked leaders—including his daughter-in-law—who have reportedly imposed loyalty tests on prospective job applicants, asking whether they believe the false assertion that the 2020 election was stolen. (The RNC has denied there is a litmus test.) Trump tells me he would have trouble hiring anyone who admits Biden won: “I wouldn’t feel good about it.”

Policy groups are creating a government-in-waiting full of true believers. The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 has drawn up plans for legislation and Executive Orders as it trains prospective personnel for a second Trump term. The Center for Renewing America, led by Russell Vought, Trump’s former director of the Office of Management and Budget, is dedicated to disempowering the so-called administrative state, the collection of bureaucrats with the power to control everything from drug-safety determinations to the contents of school lunches. The America First Policy Institute is a research haven of pro-Trump right-wing populists. America First Legal, led by Trump’s immigration adviser Stephen Miller, is mounting court battles against the Biden Administration.

The goal of these groups is to put Trump’s vision into action on day one. “The President never had a policy process that was designed to give him what he actually wanted and campaigned on,” says Vought. “[We are] sorting through the legal authorities, the mechanics, and providing the momentum for a future Administration.” That includes a litany of boundary-pushing right-wing policies, including slashing Department of Justice funding and cutting climate and environmental regulations.

Read More: Fact-Checking What Donald Trump Said in His 2024 Interviews With TIME

Trump’s campaign says he would be the final decision-maker on which policies suggested by these organizations would get implemented. But at the least, these advisers could form the front lines of a planned march against what Trump dubs the Deep State, marrying bureaucratic savvy to their leader’s anti-bureaucratic zeal. One weapon in Trump’s second-term “War on Washington” is a wonky one: restoring the power of impoundment, which allowed Presidents to withhold congressionally appropriated funds. Impoundment was a favorite maneuver of Nixon, who used his authority to freeze funding for subsidized housing and the Environmental Protection Agency. Trump and his allies plan to challenge a 1974 law that prohibits use of the measure, according to campaign policy advisers.

Another inside move is the enforcement of Schedule F, which allows the President to fire nonpolitical government officials and which Trump says he would embrace. “You have some people that are protected that shouldn’t be protected,” he says. A senior U.S. judge offers an example of how consequential such a move could be. Suppose there’s another pandemic, and President Trump wants to push the use of an untested drug, much as he did with hydroxychloroquine during COVID-19. Under Schedule F, if the drug’s medical reviewer at the Food and Drug Administration refuses to sign off on its use, Trump could fire them, and anyone else who doesn’t approve it. The Trump team says the President needs the power to hold bureaucrats accountable to voters. “The mere mention of Schedule F,” says Vought, “ensures that the bureaucracy moves in your direction.”

It can be hard at times to discern Trump’s true intentions. In his interviews with TIME, he often sidestepped questions or answered them in contradictory ways. There’s no telling how his ego and self-destructive behavior might hinder his objectives. And for all his norm-breaking, there are lines he says he won’t cross. When asked if he would comply with all orders upheld by the Supreme Court, Trump says he would.

But his policy preoccupations are clear and consistent. If Trump is able to carry out a fraction of his goals, the impact could prove as transformative as any presidency in more than a century. “He’s in full war mode,” says his former adviser and occasional confidant Stephen Bannon. Trump’s sense of the state of the country is “quite apocalyptic,” Bannon says. “That’s where Trump’s heart is. That’s where his obsession is.”

These obsessions could once again push the nation to the brink of crisis. Trump does not dismiss the possibility of political violence around the election. “If we don’t win, you know, it depends,” he tells TIME. “It always depends on the fairness of the election.” When I ask what he meant when he baselessly claimed on Truth Social that a stolen election “allows for the termination of all rules, regulations and articles, even those found in the Constitution,” Trump responded by denying he had said it. He then complained about the “Biden-inspired” court case he faces in New York and suggested that the “fascists” in America’s government were its greatest threat. “I think the enemy from within, in many cases, is much more dangerous for our country than the outside enemies of China, Russia, and various others,” he tells me.

Toward the end of our conversation at Mar-a-Lago, I ask Trump to explain another troubling comment he made: that he wants to be dictator for a day. It came during a Fox News town hall with Sean Hannity, who gave Trump an opportunity to allay concerns that he would abuse power in office or seek retribution against political opponents. Trump said he would not be a dictator—“except for day one,” he added. “I want to close the border, and I want to drill, drill, drill.”

Trump says that the remark “was said in fun, in jest, sarcastically.” He compares it to an infamous moment from the 2016 campaign, when he encouraged the Russians to hack and leak Hillary Clinton’s emails. In Trump’s mind, the media sensationalized those remarks too. But the Russians weren’t joking: among many other efforts to influence the core exercise of American democracy that year, they hacked the Democratic National Committee’s servers and disseminated its emails through WikiLeaks.

Whether or not he was kidding about bringing a tyrannical end to our 248-year experiment in democracy, I ask him, Don’t you see why many Americans see such talk of dictatorship as contrary to our most cherished principles? Trump says no. Quite the opposite, he insists. “I think a lot of people like it.” —With reporting by Leslie Dickstein, Simmone Shah, and Julia Zorthian