MSNBC – Opinion

The Supreme Court has signed off on a Trump takeover of the DOJ

Hayes Brown – July 3, 2024

In the process of granting former President Donald Trump immunity for at least some of his actions between Election Day 2020 and Jan. 6, 2021, the Supreme Court’s sweeping decision also provided a stamp of approval for one of the most dangerous parts of Trump’s second-term agenda: payback. In doing so, the justices rolled back one of the key post-Watergate reforms preventing presidents from abusing their vast power, freeing Trump, if he’s re-elected, to use the Department of Justice as his personal weapon.

The scheme Trump and his allies cooked up in 2020 involved enlisting the Justice Department to give their lies about widespread election fraud an official patina. Then-Justice Department lawyer Jeffrey Clark drafted a letter to send to several states, including Georgia, that would falsely claim that “various irregularities” existed that cast those states’ election results into doubt. Had it been sent, the letter would have encouraged those state legislatures to convene special sessions to “investigate” and potentially send to Congress slates flipping the states’ Electoral College votes to Trump.

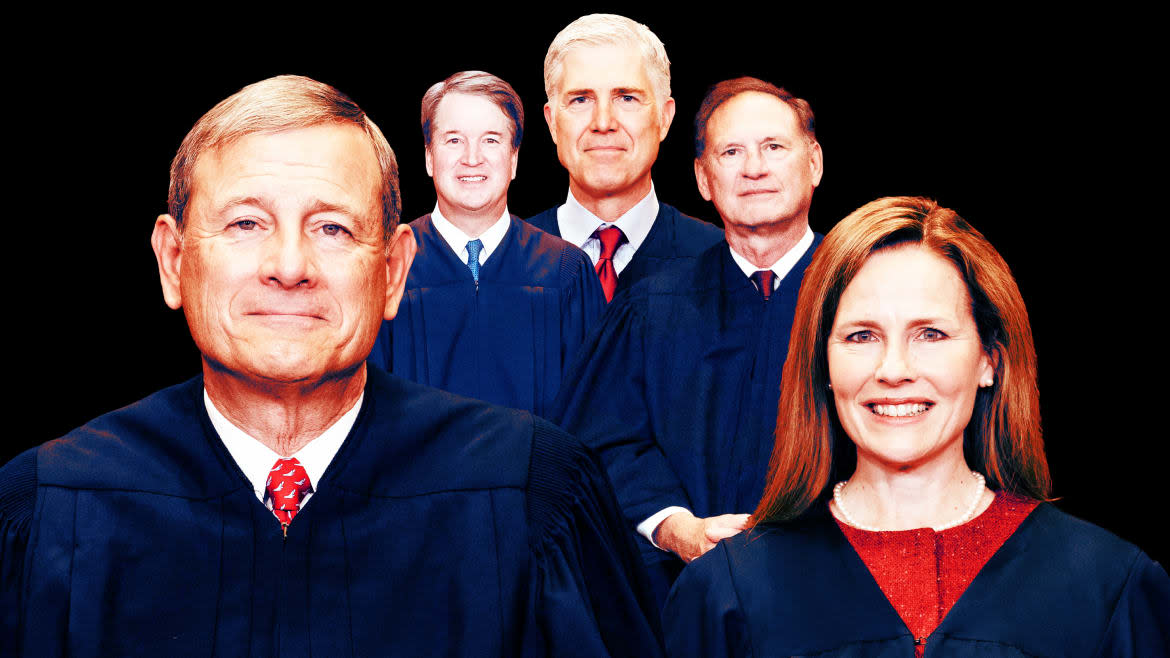

When the acting attorney general refused to send the letter, Trump threatened to fire him and replace him with Clark. He yielded only when a slew of top Justice Department officials promised to resign in protest. Apparently, though, according to the Supreme Court, there was nothing about that chain of events that falls outside the scope of the president’s “official acts.” As Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the 6-3 opinion, “The President may discuss potential investigations and prosecutions with his Attorney General and other Justice Department officials to carry out his constitutional duty to ‘take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.’”

The line seems innocuous compared to some of the other more dumbfounding statements within the decision, but the problem is that it’s written as though there was nothing wrong about the content of those discussions. A few paragraphs later, Roberts clarifies that sentence’s importance in explaining why the pressure campaign against Justice Department officials can’t be used to as part of the federal case against Trump:

Putting those two ideas together effectively signs off on ending the last 50 years of Justice Department independence. The way then-President Richard Nixon and his attorney general, John Mitchell, used and abused the DOJ and other law enforcement bodies to shield Nixon’s allies and harass his enemies was one of the most damaging revelations of Watergate. Following Nixon’s resignation and Mitchell’s eventual prosecution and conviction, subsequent attorneys general have all strived to keep the White House at arm’s length from the day-to-day decisions regarding investigations.

But there were few legislative reforms that safeguarded the Justice Department from being used as a political tool — it has almost entirely been the work of norms and precedents that have cut across administrations. Even Trump’s White House counsel Don McGahn issued a memo at the beginning of his term laying out the firewall between the White House staff and the Justice Department. It’s a standard that Trump’s allies, including Clark, have railed against, making no bones about the fact that, if given the chance, they intend to tear it down entirely.

If that happens, there will be little to prevent Trump from launching his promised revenge campaign against his enemies. Given the leeway Roberts has granted for the president to order even “sham” investigations, anyone could be subject to arbitrary probes, prompting unnecessary (and expensive) legal defenses and social stigma. It’s not absurd to imagine this resulting in the arrest and detention on made-up charges for anyone on the long list of people who’ve earned Trump’s ire.

Conversely, this ruling also seems on its face to allow a president to order an investigation to end for any reason. Under Roberts’ test, there would be no means for a court to assess, for example, whether Trump’s corruptly ordering that a GOP megadonor be beyond Justice Department scrutiny was a criminal violation of the law. Instead, the court’s conservatives have chosen to write this opinion from a worldview that assumes every “official act” taken by the president within his authority is legal and constitutional.

Roberts attempted to give the illusion that opinion was written with anyone but Trump in mind, and in doing so, he obscured how far removed from the average president Trump is. What Roberts frames as a simple declaration of the president’s authorities under the Constitution is now poised to become Trump’s go-ahead to target the political opposition with impunity. Likewise, in granting presidents the broadest benefit of the doubt possible to “take care that the laws are faithfully executed,” the court has all but guaranteed that, if Trump is returned to power, he will do the exact opposite.