The Guardian

Death and Dying

Why are the poor blamed and shamed for their deaths?

When someone dies, she often suffers a brutal moral autopsy, says Barbara Ehrenreich. Did she smoke? Drink excessively? Eat too much fat?

Barbara Ehrenreich March 31, 2018

Barbara Ehrenreich: ‘Friends berate me for my heavy use of butter.’ Photograph: Stephen Voss for the Guardian

Barbara Ehrenreich: ‘Friends berate me for my heavy use of butter.’ Photograph: Stephen Voss for the Guardian

I watched in dismay as most of my educated, middle-class friends began, at the onset of middle age, to obsess about their health and likely longevity. Even those who were at one point determined to change the world refocused on changing their bodies. They undertook exercise or yoga regimens; they filled their calendars with medical tests and exams; they boasted about their “good” and “bad” cholesterol counts, their heart rates and blood pressure.

Mostly they understood the task of ageing to be self-denial, especially in the realm of diet, where one medical fad, one study or another, condemned fat and meat, carbs, gluten, dairy or all animal-derived products. In the health-conscious mindset that has prevailed among the world’s affluent people for about four decades now, health is indistinguishable from virtue, tasty foods are “sinfully delicious”, while healthful foods may taste good enough to be advertised as “guilt-free”. Those seeking to compensate for a lapse undertake punitive measures such as hours-long cardio sessions, fasts, purges or diets composed of different juices carefully sequenced throughout the day.

Of course I want to be healthy, too; I just don’t want to make the pursuit of health into a major life project. I eat well, meaning I choose foods that taste good and will stave off hunger for as long as possible, such as protein, fiber and fats. But I refuse to over think the potential hazards of blue cheese on my salad or pepperoni on my pizza. I also exercise – not because it will make me live longer but because it feels good when I do. As for medical care, I will seek help for an urgent problem, but I am no longer interested in undergoing tests to uncover problems that remain undetectable to me. When friends berate me for my laxity, my heavy use of butter or habit of puffing (but not inhaling) on cigarettes, I gently remind them that I am, in most cases, older than they are.

So it was with a measure of schadenfreude that I began to record the cases of individuals whose healthy lifestyles failed to produce lasting health. It turns out that many of the people who got caught up in the health “craze” of the last few decades – people who exercised, watched what they ate, abstained from smoking and heavy drinking – have nevertheless died. Lucille Roberts, owner of a chain of women’s gyms, died incongruously from lung cancer at the age of 59, although she was a “self-described exercise nut” who, the New York Times reported, “wouldn’t touch a French fry, much less smoke a cigarette”. Jerry Rubin, who devoted his later years to trying every supposedly health-promoting diet fad, therapy and meditation system he could find, jaywalked into Wilshire Boulevard at the age of 56 and died of his injuries two weeks later.

Some of these deaths were genuinely shocking. Jim Fixx, author of the bestselling The Complete Book Of Running, believed he could outwit the cardiac problems that had carried his father off to an early death by running at least 10 miles a day and restricting himself to a diet of pasta, salads and fruit. But he was found dead on the side of a Vermont road in 1984, aged only 52.

Even more disturbing was the untimely demise of John H Knowles, director of the Rockefeller Foundation and promulgator of the “doctrine of personal responsibility” for one’s health. Most illnesses are self-inflicted, he argued – the result of “gluttony, alcoholic intemperance, reckless driving, sexual frenzy, smoking” and other bad choices. The “idea of a ‘right’ to health,” he wrote, “should be replaced by the idea of an individual moral obligation to preserve one’s own health.” But he died of pancreatic cancer at 52, prompting one physician commentator to observe, “Clearly we can’t all be held responsible for our health.”

Still, we persist in subjecting anyone who dies at a seemingly untimely age to a kind of bio-moral autopsy: did she smoke? Drink excessively? Eat too much fat and not enough fiber? Can she, in other words, be blamed for her own death? When David Bowie and Alan Rickman both died in early 2016 of what major US newspapers described only as “cancer”, some readers complained that it is the responsibility of obituaries to reveal what kind of cancer. Ostensibly, this information would help promote “awareness” of the particular cancers involved, as Betty Ford’s openness about her breast cancer diagnosis helped to de-stigmatize that disease. It would also, of course, prompt judgments about the victim’s “lifestyle”. Would Bowie have died – at the quite respectable age of 69 – if he hadn’t been a smoker?

With sufficient ingenuity – or malicious intent – almost any death can be blamed on some mistake of the deceased.

Apple co-founder Steve Jobs’ 2011 death from pancreatic cancer continues to spark debate. He was a food faddist, eating only raw vegan foods, especially fruit, and refusing to deviate from that plan even when doctors recommended a high protein and fat diet to help compensate for his failing pancreas. His office refrigerator was filled with Odwalla juices; he antagonized non-vegan associates by attempting to proselytize among them, as biographer Walter Isaacson has reported: at a meal with Mitch Kapor, the chairman of Lotus software, Jobs was horrified to see Kapor slathering butter on his bread, and asked, “Have you ever heard of serum cholesterol?” Kapor responded, “I’ll make you a deal. You stay away from commenting on my dietary habits, and I will stay away from the subject of your personality.”

Defenders of veganism argue that his cancer could be attributed to his occasional forays into protein-eating (a meal of eel sushi has been reported) or to exposure to toxic metals as a young man tinkering with computers. But a case could be made that it was the fruitarian diet that killed him: metabolically, a diet of fruit is equivalent to a diet of candy, only with fructose instead of glucose, with the effect that the pancreas is strained to constantly produce more insulin. As for the personality issues – the almost manic-depressive mood swings – they could be traced to frequent bouts of hypoglycemia. Incidentally, 67-year-old Mitch Kapor is alive and well at the time of this writing.

Similarly, with sufficient ingenuity – or malicious intent – almost any death can be blamed on some mistake of the deceased. Surely Fixx had failed to “listen to his body” when he first felt chest pains and tightness while running, and maybe, if he had been less self-absorbed, Rubin would have looked both ways before crossing the street. Maybe it’s just the way the human mind works, but when bad things happen or someone dies, we seek an explanation, preferably one that features a conscious agent – a deity or spirit, an evil-doer or envious acquaintance, even the victim. We don’t read detective novels to find out that the universe is meaningless, but that, with sufficient information, it all makes sense. We can, or think we can, understand the causes of disease in cellular and chemical terms, so we should be able to avoid it by following the rules laid down by medical science: avoiding tobacco, exercising, undergoing routine medical screening and eating only foods currently considered healthy. Anyone who fails to do so is inviting an early death. Or, to put it another way, every death can now be understood as suicide.

Liberal commentators countered that this view represented a kind of “victim-blaming”. In her books Illness As Metaphor and Aids And Its Metaphors, Susan Sontag argued against the oppressive moralizing of disease, which was increasingly portrayed as an individual problem. The lesson, she said, was, “Watch your appetites. Take care of yourself. Don’t let yourself go.” Even breast cancer, she noted, which has no clear lifestyle correlates, could be blamed on a “cancer personality”, sometimes defined in terms of repressed anger which, presumably, one could have sought therapy to cure. Little was said, even by the major breast cancer advocacy groups, about possible environmental carcinogens or carcinogenic medical regimes such as hormone replacement therapy.

While the affluent struggled dutifully to conform to the latest prescriptions for healthy living – adding whole grains and gym time to their daily plans – the less affluent remained mired in the old comfortable, unhealthy ways of the past – smoking cigarettes and eating foods they found tasty and affordable. There are some obvious reasons why the poor and the working class resisted the health craze: gym memberships can be expensive; “health foods” usually cost more than “junk food”. But as the classes diverged, the new stereotype of the lower classes as willfully unhealthy quickly fused with their old stereotype as semi-literate louts. I confront this in my work as an advocate for a higher minimum wage. Affluent audiences may cluck sympathetically over the miserably low wages offered to blue-collar workers, but they often want to know “why these people don’t take better care of themselves”. Why do they smoke or eat fast food? Concern for the poor usually comes tinged with pity. And contempt.

Photograph: Stephen Voss for the Guardian

Photograph: Stephen Voss for the Guardian

In the 00’s, British celebrity chef Jamie Oliver took it on himself to reform the eating habits of the masses, starting with school lunches. Pizza and burgers were replaced with menu items one might expect to find in a restaurant – fresh greens, for example, and roast chicken. But the experiment was a failure. In the US and UK, schoolchildren dumped out their healthy new lunches or stamped them underfoot. Mothers passed burgers to their children through school fences. Administrators complained that the new meals were vastly over-budget; nutritionists noted that they were cruelly deficient in calories. In Oliver’s defense, it should be observed that ordinary “junk food” is chemically engineered to provide an addictive combination of salt, sugar and fat. But it probably matters, too, that he didn’t study local eating habits in sufficient depth before challenging them, nor seems to have given enough thought to creatively modifying them. In West Virginia, he alienated parents by bringing a local mother to tears when he publicly announced the food she gave her four children was “killing” them.

There may well be unfortunate consequences from eating the wrong foods. But what are the “wrong” foods? In the 80’s and 90’s, the educated classes turned against fat in all forms, advocating the low-fat and protein diet that, journalist Gary Taubes argues, paved the way for an “epidemic of obesity” as health-seekers switched from cheese cubes to low-fat desserts. The evidence linking dietary fat to poor health had always been shaky, but class prejudice prevailed: fatty and greasy foods were for the poor and unenlightened; their betters stuck to bone-dry biscotti and fat-free milk. Other nutrients went in and out of style as medical opinion shifted: it turns out high dietary cholesterol, as in oysters, is not a problem after all, and doctors have stopped pushing calcium on women over 40. Increasingly, the main villains appear to be sugar and refined carbohydrates, as in hamburger buns. Eat a pile of fries washed down with a sugary drink and you will probably be hungry again in a couple of hours, when the sugar rush subsides. If the only cure for that is more of the same, your blood sugar levels may permanently rise – what we call diabetes.

Special opprobrium is attached to fast food, thought to be the food of the ignorant. Film-maker Morgan Spurlock spent a month eating nothing but McDonald’s to create his famous Super Size Me, documenting his 11 kg (24 lb) weight gain and soaring blood cholesterol. I have also spent many weeks eating fast food because it’s cheap and filling but, in my case, to no perceptible ill effects. It should be pointed out, though, that I ate selectively, skipping the fries and sugary drinks to double down on the protein. When, at a later point, a notable food writer called to interview me on the subject of fast food, I started by mentioning my favorites (Wendy’s and Popeye’s), but it turned out they were all indistinguishable to him. He wanted a comment on the general category, which was like asking me what I thought about restaurants.

I grew up in the 1940s and 50s, when cigarettes served not only as a comfort for the lonely but a powerful social glue.

If food choices defined the class gap, smoking provided a firewall between the classes. To be a smoker in almost any modern, industrialized country is to be a pariah and, most likely, a sneak. I grew up in another world, in the 1940’s and 50’s, when cigarettes served not only as a comfort for the lonely but a powerful social glue. People offered each other cigarettes, and lights, indoors and out, in bars, restaurants, workplaces and living rooms, to the point where tobacco smoke became, for better or worse, the scent of home. My parents smoked; one of my grandfathers could roll a cigarette with one hand; my aunt, who was eventually to die of lung cancer, taught me how to smoke when I was a teenager. And the government seemed to approve. It wasn’t till 1975 that the armed forces stopped including cigarettes along with food rations.

As more affluent people gave up the habit, the war on smoking – which was always presented as an entirely benevolent effort – began to look like a war against the working class. When the break rooms offered by employers banned smoking, workers were forced outdoors, leaning against walls to shelter their cigarettes from the wind. When working-class bars went non-smoking, their clienteles dispersed to drink and smoke in private, leaving few indoor sites for gatherings and conversations. Escalating cigarette taxes hurt the poor and the working class hardest. The way out is to buy single cigarettes on the streets, but strangely enough the sale of these “loosies” is largely illegal. In 2014 a Staten Island man, Eric Garner, was killed in a chokehold by city police for precisely this crime.

Why do people smoke? I once worked in a restaurant in the era when smoking was still permitted in break rooms, and many workers left their cigarettes burning in the common ashtray so they could catch a puff whenever they had a chance to, without bothering to relight. Everything else they did was done for the boss or the customers; smoking was the only thing they did for themselves. In one of the few studies of why people smoke, a British sociologist found smoking among working-class women was associated with greater responsibilities for the care of family members – again suggesting a kind of defiant self-nurturance.

When the notion of “stress” was crafted in the mid-20th century, the emphasis was on the health of executives, whose anxieties presumably outweighed those of the manual laborer who had no major decisions to make. It turns out, however, that stress – measured by blood levels of the stress hormone cortisol – increases as you move down the socioeconomic scale, with the most stress inflicted on those who have the least control over their work. In the restaurant industry, stress is concentrated among the people responding to the minute-by-minute demands of customers, not those who sit in offices discussing future menus. Add to these workplace stresses the challenges imposed by poverty and you get a combination that is highly resistant to, for example, anti-smoking propaganda – as Linda Tirado reported about her life as a low-wage worker with two jobs and two children: “I smoke. It’s expensive. It’s also the best option. You see, I am always, always exhausted. It’s a stimulant. When I am too tired to walk one more step, I can smoke and go for another hour. When I am enraged and beaten down and incapable of accomplishing one more thing, I can smoke and I feel a little better, just for a minute. It is the only relaxation I am allowed.”

Nothing has happened to ease the pressures on low-wage workers. On the contrary, if the old paradigm of a blue-collar job was 40 hours a week, an annual two-week vacation and benefits such as a pension and health insurance, the new expectation is that one will work on demand, as needed, without benefits or guarantees. Some surveys now find a majority of US retail staff working without regular schedules – on call for when an employer wants them to come and unable to predict how much they will earn. With the rise in “just in time” scheduling, it becomes impossible to plan ahead: will you have enough money to pay the rent? Who will take care of the children? The consequences of employee “flexibility” can be just as damaging as a program of random electric shocks applied to caged laboratory animals.

Sometime in the early to mid-00’s, demographers noticed an unexpected rise in the death rates of poor white Americans. This was not supposed to happen. For almost a century, the comforting American narrative was that better nutrition and medical care would guarantee longer lives for all. It was especially not supposed to happen to whites who, in relation to people of color, have long had the advantage of higher earnings, better access to healthcare, safer neighborhoods and freedom from the daily insults and harms inflicted on the darker skinned. But the gap between the life expectancy of blacks and whites has been narrowing. The first response of some researchers – themselves likely to be well above the poverty level – was to blame the victims: didn’t the poor have worse health habits? Didn’t they smoke?

The class gap in mortality will not be closed by tweaking individual tastes.

In late 2015, the British economist Angus Deaton won the Nobel prize for work he had done with Anne Case, showing that the mortality gap between wealthy white men and poor ones was widening at a rate of one year a year, and slightly less for women. Smoking could account for only one fifth to one third of the excess working-class deaths. The rest were apparently attributable to alcoholism, opioid addiction and actual suicide – as opposed to metaphorically “killing” oneself through unwise lifestyle choices.

Why the excess mortality among poor white Americans? In the last few decades, things have not been going well for working-class people of any color. I grew up in an America where a man with a strong back – and a strong union – could reasonably expect to support a family on his own without a college degree. By 2015, those jobs were long gone, leaving only the kind of work once relegated to women and people of color available in areas such as retail, landscaping and delivery truck driving. This means those in the bottom 20% of the white income distribution face material circumstances like those long familiar to poor blacks, including erratic employment and crowded, hazardous living spaces. Poor whites always had the comfort of knowing that someone was worse off and more despised than they were; racial subjugation was the ground under their feet, the rock they stood upon, even when their own situation was deteriorating. That slender reassurance is shrinking.

There are some practical reasons why whites are likely to be more efficient than blacks at killing themselves. For one thing, they are more likely to be gun owners, and white men favour gunshot as a means of suicide. For another, doctors, undoubtedly acting on stereotypes of non-whites as drug addicts, are more likely to prescribe powerful opioid painkillers to whites. Pain is endemic among the blue-collar working class, from waitresses to construction workers, and few people make it past 50 without palpable damage to their knees, back or shoulders. As opioids became more expensive and closely regulated, users often made the switch to heroin which, being illegal, can vary widely in strength, leading to accidental overdoses.

Affluent reformers are perpetually frustrated by the unhealthy habits of the poor, but it is hard to see how problems arising from poverty – and damaging work conditions – could be cured by imposing the doctrine of “personal responsibility”. I have no objections to efforts encouraging people to stop smoking or add more vegetables to their diets. But the class gap in mortality will not be closed by tweaking individual tastes. This is an effort that requires concerted action on a vast scale: a welfare state to alleviate poverty; environmental clean-up of, for example, lead in drinking water; access to medical care including mental health services; occupational health reform to reduce disabilities inflicted by work.

The wealthier classes will also benefit from these measures, but what they need right now is a little humility. We will all die – whether we slake our thirst with kombucha or Coca-Cola, whether we run five miles a day or remain confined to our trailer homes, whether we dine on quinoa or KFC. This is the human condition. It’s time we began facing it together.

This is an edited extract from Natural Causes, by Barbara Ehrenreich, published by Granta on 12 April at £16.99. To order a copy for £14.44, go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Commenting on this piece? If you would like your comment to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).

After much research and soul-searching, they decided to accept Siemon’s offer and started the transition process. It helped that his cousin Dan had transitioned one of his farms to organic not long before and that generations of his family before him had run pasture-based dairies.

After much research and soul-searching, they decided to accept Siemon’s offer and started the transition process. It helped that his cousin Dan had transitioned one of his farms to organic not long before and that generations of his family before him had run pasture-based dairies. Scientific research seems to bear out his hypothesis. A

Scientific research seems to bear out his hypothesis. A

From Esquire

From Esquire

Field test-spraying of glyphosate. (Photo credit:

Field test-spraying of glyphosate. (Photo credit:  Farm tractor spraying crops. (Photo credit:

Farm tractor spraying crops. (Photo credit:  Corn seed genetically engineered to withstand glyphosate spray. (Photo credit:

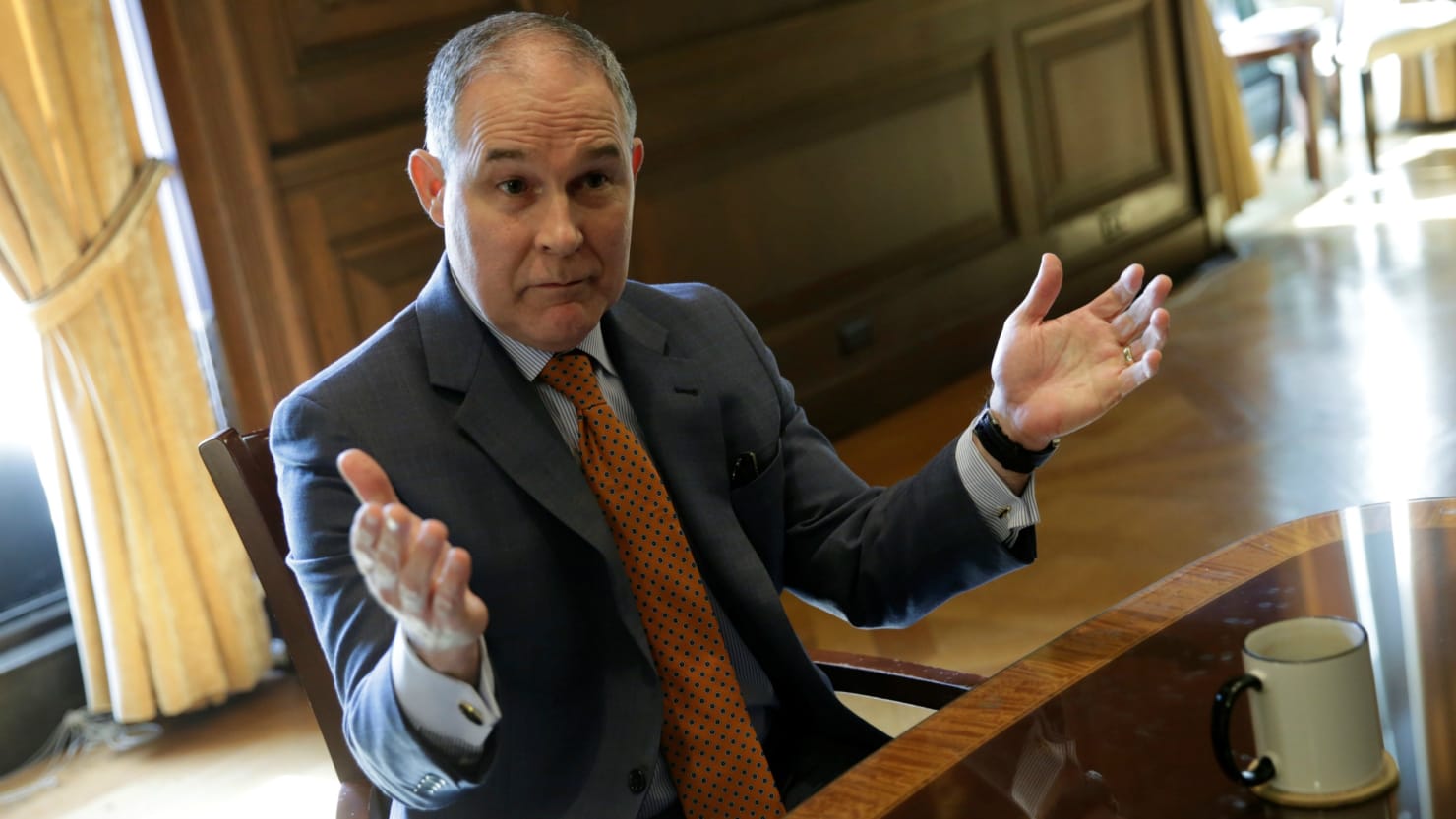

Corn seed genetically engineered to withstand glyphosate spray. (Photo credit:  Scott Pruitt: Everything you need to know

Scott Pruitt: Everything you need to know ABC News. A townhouse near the U.S. Capitol where EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt is said to have stayed. The building is co-owned by the wife of a top energy lobbyist, property records from 2017 show.

ABC News. A townhouse near the U.S. Capitol where EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt is said to have stayed. The building is co-owned by the wife of a top energy lobbyist, property records from 2017 show.  Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, right, meets with Moroccan Minister of Energy, Mines and Sustainable Development, Aziz Rabbah during a trip to Morocco in December of 2017.

Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, right, meets with Moroccan Minister of Energy, Mines and Sustainable Development, Aziz Rabbah during a trip to Morocco in December of 2017.  Obtained by ABC News. A photo obtained by ABC News shows EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt deplaning a military-owned plane in June 2017 at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport.

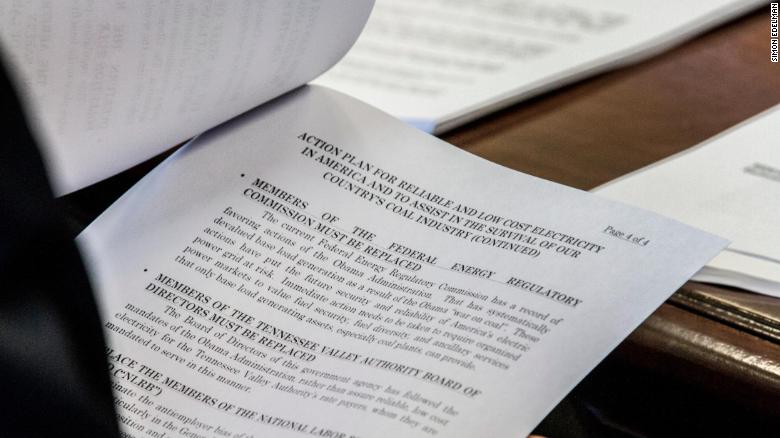

Obtained by ABC News. A photo obtained by ABC News shows EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt deplaning a military-owned plane in June 2017 at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport.  Simon Edelman

Simon Edelman Secretary of Energy Rick Perry reviews Murray Energy CEO Robert Murray’s “action plan.”

Secretary of Energy Rick Perry reviews Murray Energy CEO Robert Murray’s “action plan.” Secretary of Energy Rick Perry and Murray Energy CEO Robert Murray meet.

Secretary of Energy Rick Perry and Murray Energy CEO Robert Murray meet. Veterans Affairs Secretary David Shulkin testifies before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee on Sept. 27, 2017 in Washington, D.C. Win McNamee/Getty Images

Veterans Affairs Secretary David Shulkin testifies before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee on Sept. 27, 2017 in Washington, D.C. Win McNamee/Getty Images

EPA plans to roll back major Obama-era climate rule

EPA plans to roll back major Obama-era climate rule Scott J. Ferrell/CQ-Roll Call via Getty Images, FILE. Chairman Lamar Smith, R-Texas, listens during the House Judiciary hearing on medical liability issues.

Scott J. Ferrell/CQ-Roll Call via Getty Images, FILE. Chairman Lamar Smith, R-Texas, listens during the House Judiciary hearing on medical liability issues. Republicans propose a balanced budget amendment after voting for trillion dollar legislation. Credit: Alex Edelman-Pool/Getty Images.

Republicans propose a balanced budget amendment after voting for trillion dollar legislation. Credit: Alex Edelman-Pool/Getty Images.