Resilience

Tiny Houses Alone Can’t Solve the Housing Crisis. But Here’s What Can.

By Chris Winters, orig. pub. by Yes Magazine May 25, 2018

For Julia Rosenblatt, the solution to affordable housing was to move in with friends and family—more than 10 people under one roof.

For Julia Rosenblatt, the solution to affordable housing was to move in with friends and family—more than 10 people under one roof.

Rosenblatt, a co-founder of the HartBeat Ensemble theater group in Hartford, Connecticut, had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances in local activist communities. The year was 2003, the United States had launched a war in Iraq, and the post-9/11 environment was making her think differently about what kind of life she was going to have for herself and her family. An initial group of about 20 people liked the idea of creating an intentional community: living together with a shared set of goals and values to have a life that would be more meaningful, less harmful to other communities and the environment—and more affordable.

In 2008, six people moved into one house. The big move came in 2014, when those six were joined by five more to buy a 5,800-square-foot 1921 house on Tony Scarborough Street in the city’s West End. The nine-bedroom house had been sitting empty for four years.

Rosenblatt, her husband, Joshua Blanchfield, and their children, Tessa and Elijah Rosenfield (a merging of their parents’ last names), now live with Dave and Laura Rozza and their son, Milo, plus another married couple, Maureen Welch and Simon DeSantis, and Hannah Simms. The other original group member left the home when he got married.

Everyone contributed to the down payment. DeSantis and Laura Rozza had the best credit, so the mortgage for the $453,000 purchase price was taken out in their names, while a separate legal agreement stipulates that everyone is a co-owner of the house.

“We couldn’t maintain ourselves as a four-person household,” Rosenblatt says. “There was no way we could have bought this house at all with any less than eight adults pitching in.”

There were additional considerations, too.

“It was the idea of sort of creating a new world we want to live in,” says Laura Rozza, a grant writer for a nonprofit serving people with disabilities.

“The idea of the American Dream in 2003 was unobtainable for the majority of people,” says Dave Rozza, a math tutor.

The city of Hartford disagreed with their idea of what constitutes a household and sued the group, saying that multiple adults who were not all related couldn’t live together in a single-family dwelling under the city’s zoning laws. The city dropped the case after a year and a half but hasn’t changed its codes, leaving the group in a sort of legal limbo.

Most families make similar calculations involving costs, parenting needs, and how their values are reflected in the living arrangements they choose. For the merged families in Hartford, their choice became a radical declaration of independence from societal expectations, and it’s one small story in an epic housing affordability crisis unfolding across the U.S.

In many ways, this is a continuation of the housing market collapse of 2008, after the mortgage industry took advantage of loose regulations and overextended its lending. A lot of that was driven by Wall Street, which packaged subprime and other loans into exotic financial instruments that concealed the weakness in those debts.

When the financial crash came, it took the housing market with it. A wave of foreclosures arrived—more than 2.3 million properties received foreclosure notices in 2008 alone, according to RealtyTrac, and another 2.8 million in 2009. That was accompanied by home seizures (more than 1 million families lost their homes in 2010), job losses, and the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

A decade later, with major economic indicators on the rebound in many places, the housing crisis has turned into an epidemic of unaffordability: too few homes are available where they’re needed, and those that are, whether for sale or for rent, are increasingly out of reach for people whose incomes have effectively stagnated.

There’s no overall shortage of homes; the affordability challenge is different in each city. According to federal government data, the overall housing market has more than kept up with population growth. What’s happened instead is a split.

In hot markets like the technology centers of the West Coast, competition for housing has driven up both rents and sale prices. Seattle is home to fast-growing Amazon and also the highest annual price increases in the country, 12.86 percent as of January. The median sale price in the city has surpassed $800,000.

But in cities still recovering from the housing market collapse, such as those in the Rust Belt, there are plenty of vacant houses. It’s decent-paying jobs that are scarcer, and many of those vacant houses are still owned by banks that are unlikely to sell until the market turns around. In Detroit, prices are going up at a more modest 7.6 percent per year, but there are still an estimated 25,000 vacant houses in the city that were lost to foreclosure over the years.

After buying the West End house—a single-family dwelling—the group had to battle the city over definitions of family and household. Photo by Chris Marion.

After buying the West End house—a single-family dwelling—the group had to battle the city over definitions of family and household. Photo by Chris Marion.

That, topped off with stagnant wages, has resulted in a lack of housing many people can afford either to rent or buy. The average wage for a non-managerial employee at the beginning of 1979 was $22.51 per hour in 2018 dollars. In March 2018, it was $22.44 per hour, essentially flat. In that same 40-year period, housing prices have gone up nearly 50 percent, from a median price of $60,300 ($220,300 in today’s dollars) to $326,800 today.

What Seattle and Detroit share is a large percentage of the population considered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to be cost-burdened: households spending more than 30 percent of income on housing. A study by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University estimated that in the greater Seattle area, 33.4 percent of both rental and owner households fit that description in 2015. In Detroit, 31.4 percent did.

These are not unique situations: Nationwide, 1 in 3 households is spending more than 30 percent of income for a home.

With that kind of math working against them, people have had to get creative.

Multiple solutions

There is no single solution to the housing equation. As communities grapple with housing costs, what is clear is that cooperation and coordination among government, private developers, the nonprofit community, and individuals at all income levels is required.

Solutions will have to be intensely customized by location. What works in a fast-growing city like Seattle won’t work in a city like Detroit, and what helps build more houses to sell is different from what creates more rental units.

Consider all the collaboration, innovation—and compassion—over the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, a suburb about 12 miles south of Salt Lake City: 56 homes, reserved for adults 55 or older, mostly seniors. Most of them owned their own single- or double-wides, but they had to pay $320 per month as a lot fee—leasing the spots where their homes sit.

Most of the residents are retired and on fixed incomes, says Shirlene Stoven, 81, who has lived there since 1994.

In 2013, the owner of the park sold to a large developer, Ivory Homes. The site is situated between two TRAX light rail stations, and the zoning allowed for dense development.

First, the monthly lot fees went up by $89. Six months later, they went up by another $89.

Stoven learned that Ivory had filed plans for a three-story multifamily building there. “We realized what they were up to, to financially squeeze us out,” Stoven says.

But rather than roll over, Stoven got organized. The Applewood residents formed a homeowners association and began a signature drive to try to stop the development and displacement. They swamped city council meetings with neighbors from the wider community.

There are more renters now than ever before: 43.3 million in 2017, nearly 10 million more than just before the recession, according to Pew Research. Photo by Chris Marion.

There are more renters now than ever before: 43.3 million in 2017, nearly 10 million more than just before the recession, according to Pew Research. Photo by Chris Marion.

And the city listened. In the end, the park was downzoned to 25 units per acre, so Ivory decided to sell it. But the land was still attractive to developers, and the competition drove the purchase price up to $4.8 million.

“I thought, ‘Oh, here we go again,’” Stoven says.

But Stoven, who was elected president of the new association, told their story to the new buyers, who decided to give the residents the opportunity to buy their park for $5 million.

How to raise that kind of money? Stoven connected with ROC USA, a nonprofit that helps mobile home owners transform their parks into resident-owned communities. The Applewood residents formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative and were able to raise the money, much of it from ROC USA and the state’s Olene Walker Housing Loan Fund, and buy the land their homes sit on. The deal closed in February.

Stoven said she’s always been tenacious, and thinks that she won the battle because the developers couldn’t intimidate her. Many of the residents in Applewood are homebound and wouldn’t have been able to mobilize for a fight the way she did.

“That’s why I had to fight for them. Because where would they go?” she says.

They’re paying higher pad fees to help with the purchase. But in doing so, they are preserving their affordable homes for the long term in a rapidly growing area.

Efforts to mitigate the affordability crisis fall into two broad categories: providing more money to people to get them into housing and providing more new housing.

Government, especially the federal government, plays an outsize role in financing below-market-rate housing. Rent subsidies, in the form of Section 8 or Housing Choice vouchers, are limited to low- and very-low-income people. Yet only about 1 in 4 households eligible for housing assistance receives it because of chronic underfunding of HUD programs.

HUD also runs the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, which provides incentives for investors to subsidize development of new affordable units. The Community Development Block Grant program also sometimes supports affordable housing projects.

However, the Trump administration has repeatedly floated the idea of eliminating the block grant program, and the LIHTC program may be adversely affected by the massive tax cuts passed by Congress in December. With the corporate tax rate cut from 35 percent to 21 percent, those tax credits just aren’t as valuable, and by some estimates that may translate into a loss of more than 200,000 affordable housing units over the next decade.

“Rental assistance really provides that bedrock of making sure people don’t have to spend a disproportionate amount of their income on rent,” says Janice Elliott, the executive director of the Melville Charitable Trust, a foundation that funds efforts to prevent and reduce homelessness.

“The least little thing and boom!—someone’s lost their home,” Elliott says.

Not enough homes

Most people in lower income brackets aren’t in the market to buy a house. Their challenge is finding rental property they can afford.

There are more renters now than ever before: 43.3 million in 2017, nearly 10 million more than just before the recession, according to Pew Research. That rise is driving up prices because developers aren’t building new units fast enough. According to the Urban Institute, for every 100 extremely low-income households, there are only 29 affordable rental units available.

It’s not much easier at higher income levels. Because wages haven’t kept up with housing costs, many more people can’t afford to buy.

And in no state in the country can someone earning the minimum wage afford the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment by working 40 hours a week. Rising homelessness in recent years has been exacerbated by precariously housed people being squeezed out of the housing market altogether. Forestalling that outcome is a challenge for low-income people.

“Homelessness is an indicator not only of what’s happening with people, but it’s also indicative of fundamental problems in the economy,” Elliott says.

On the other end of the spectrum, the city of Seattle has built so much rental housing that rents have flattened out in 2018, says Dan Bertolet, a senior researcher on housing and urbanism at Sightline Institute, a Seattle think tank. But homes for purchase are in shorter supply, with the Northwest Multiple Listing Service noting that inventory is well below the normal range.

“What we see in general is there’s a sort of perfect storm of big societal changes happening, putting pressure on housing and cities,” Bertolet says. Everyone wants to live in the city, and technology companies such as Amazon are minting millionaires at a record pace.

Shirlene Stoven, 81, organized her fellow senior housing residents in the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, and formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative. They fended off developers and were able to work with the city and nonprofits to buy the land their homes sit on. Photo by Austen Diamond.

Shirlene Stoven, 81, organized her fellow senior housing residents in the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, and formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative. They fended off developers and were able to work with the city and nonprofits to buy the land their homes sit on. Photo by Austen Diamond.

It’s a “whole bunch of factors that tell us it makes a lot more sense to put more housing in cities,” Bertolet says.

The greater Seattle area is planning for about 1.8 million more people to move there over the next 30 years, and local policies are aimed at steering much of that expected growth to areas that are already urbanized. But if they all want to buy houses, it’s a competitive market.

“One way we know we’re not keeping up is if you just look at the prices,” Bertolet says.

The city of Seattle has created more than 100,000 jobs since 2010, and a lot of that is fueled by the growth of the well-paying high-tech sector.

“Jobs really are what drives the demand for housing,” Bertolet says.

In hot housing markets like Seattle, which has large single-family neighborhoods with strong neighborhood associations wanting to keep density and growth out, construction hasn’t been able to keep up with the demand. Resistance to density is a hot-button political issue, putting upward pressure on both rent and purchase prices. Even average homes for sale have bidding wars.

But several cities have managed to keep housing prices more manageable simply by allowing developers to build more houses faster, as Sightline reported in 2017. Houston has no traditional zoning in the city, but the cheap prices come at the expense of incredible suburban sprawl. Chicago has enacted policies to speed up permitting and reduce restrictions in zoning. And Montreal’s zoning is dominated by low- and mid-rise apartment buildings. Meanwhile, Seattle has large single-family neighborhoods and a much slower and restrictive development process.

“The fundamental problem is it really is a supply-and-demand problem to a city like Seattle,” Bertolet says.

The result is a housing market like the game musical chairs, only it’s the wealthiest who win when the music stops. In a constrained market, that leaves fewer homes for people with less money. Increasing the overall number of housing units is the first step toward increasing the number of those units that are within reach of the non-rich, Bertolet says.

How to build that additional capacity, whether it’s in the far-flung suburbs or in multifamily buildings in newly up-zoned neighborhoods? Removing barriers to house-sharing could allow for more efficient use of the housing stock available, as the Hartford families have found.

Sightline advocates reducing the cost of building housing to stimulate construction. That includes zoning issues, such as raising building heights, up-zoning single-family neighborhoods, and eliminating parking requirements, which add to building costs and also take up space that could be used for housing. Regulations on building and permitting, Bertolet says, add more to housing costs than most people realize and could be reformed. That will go some way toward filling the gap, but not all the way.

“We don’t think the market will solve this problem all on its own,” Bertolet says. “There will always be a portion that can’t afford to pay for what it costs to build a home.”

What’s left

Without subsidies, what’s left is people making do and looking for alternatives.

It may be a simple case of finding roommates, an age-old option that’s been rebranded as “co-living” for young urbanites. The Rosenblatt family, the Rozzas, and the rest of their household in Hartford formalized the arrangement by buying their house and forming a limited liability corporation that determines who contributes what toward the mortgage, bills, groceries, chores, all the way down to the Netflix subscription.

The next step up from house-sharing, or co-living, is cohousing, a system of quasi-communal living in separate homes with shared common facilities.

Cohousing developments, however, tend to be composed of no more than a few dozen homes and are often not particularly affordable, in part because of newer construction standards and higher quality materials, and also because they tend to be set up by people of above-average income who aren’t necessarily looking for the cheapest possible housing. Despite a more than 30-year history in the U.S., there are only about 165 established cohousing communities, with another 140 in some stage of formation.

The more affordable option—at least from a resident’s perspective—is a community land trust. By definition it creates permanent affordability by limiting the resale price of homes situated on land owned by the trust. While it does provide affordable housing and protect against gentrification, that comes at the expense of social equity: It functions as a barrier to speculation but prevents the use of housing the way much of the country uses it—as a place to store and generate wealth.

CLTs also run up against financing challenges.

“One misconception about CLTs is that they’re somehow this magic bullet, that they’re outside the system and come with their own resources,” says Melora Hiller, the former CEO of Grounded Solutions Network, a nonprofit consulting company that helps communities set up trusts and other forms of equitable housing.

Getting funding to buy land, build, or renovate houses is often dependent on local government sources using federal funds. Those grants are limited, Hiller says, and CLTs often have to compete for that money with other nonprofit providers of low-income rental housing or homeless housing programs.

And buyers of property in community land trusts still need to qualify for a commercial mortgage. The two federal mortgage guarantors, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are committed to supporting a higher number of loans to low-income Americans, but that’s only after a commercial lender is willing to lend the money up front. “We still need the lenders for the origination before federal programs take them over,” Hiller says.

CLTs also need a lot of capital to start up and then grow. That tends to limit their size and the speed at which they grow. “Nobody’s figured out how to make it work at scale,” Bertolet says.

The latest trend is tiny houses.

Technically a trailer with a roof and walls, tiny houses are increasingly being used for infill development: bare-bones granny flats in the backyards of single-family-zoned neighborhoods or on vacant city-owned lots. The living space typically ranges from 120 to 400 square feet. The smaller sizes often exempt them from needing a building permit.

An estimate from Ryan Mitchell, the founder of The Tiny Life website, puts the number of tiny homes at 10,000 in North America, but there isn’t much documentation to support that figure. The spread of videos and TV shows like “Tiny House Nation” and “Tiny House, Big Living,” though, shows that the movement has tapped a desire among Americans to try to downsize and live more simply.

Yet despite the lower cost, small carbon footprint, and potential for DIY construction, cities and communities have been slow to change their zoning codes to allow tiny homes as infill development or transitional or emergency housing. Most cities, for example, make it illegal to live in a vehicle outside an RV park.

The money gap

In the end, the biggest bottleneck to building more affordable housing is money.

The National Cooperative Bank is likely the largest financial institution that specifically focuses on lending to community projects like cohousing or other forms of cooperatives.

The NCB reported just under $2.3 billion in assets at the end of 2016, a significant amount for the nonprofit sector. But it’s dwarfed by the commercial banks that drive the national housing market. The largest, Bank of America, has 1,000 times as much under management: $2.3 trillion in assets, including $197.8 billion in residential mortgage loans, according to its 2017 annual report.

While lending for affordable housing is part of many major banks’ portfolios, and community development financial institutions focus on all sorts of lending in distressed communities, alternative housing developers find that commercial banks are less likely to make loans outside traditional markets.

That leaves only one source with the resources to fund the wide variety of solutions necessary, at the scale necessary to address the nationwide problem, and that’s the government.

Another reason the government is an important part of the solution: In the face of market forces and housing scarcity, unlike with other commodities, there is little option not to participate. Everyone needs housing, and it’s not very portable. No solution can address the entire scope of the problem without government involvement.

The Trump administration, however, is cutting back on funding for social safety-net programs, putting many local governments under pressure.

“A local community has to have a local housing trust fund. It has to have money,” Lisa Sturtevant, a Virginia-based housing consultant, says. “It can’t do this through land use and zoning alone.”

For now, a patchwork of foundations and charities try to fill in the gap as best they can.

And where institutions fail, people step up.

The extra-large household in Hartford has been an inspiration to other people willing to challenge city laws and give creative co-living a try.

“We wanted to make it so that other people could do this, too,” Laura Rozza says about their battle with the city.

Rosenblatt says that their group has been approached by some other people interested in forming their own intentional communities, and Rozza says she regularly receives online alerts for communities that are looking at loosening their codes to accommodate alternatives to one-house-one-family norms.

It’s a system that’s worked out well for them, especially with raising children in the house.

“If I don’t have one of my own parents around, I’ll have a lot of other people around to help me with something I need,” says Tessa Rosenfield, who is 13. “Also, I’m never alone, and that’s nice to have all those people around you.”

In choosing to live in community—sharing not just a house, but their lives with each other—they’ve defined a new American Dream. They hope others will follow their model, if not by making the same choice, then by being willing to look beyond traditional boundaries.

“That just makes us intentional, as opposed to others who come together because of blood and do not share values,” Rosenblatt says. “I have one marriage to Josh and another one to each and every other person in the house.”

“It takes a lot of time and energy, like, unspeakable amounts of time and energy. To make that happen and be worth it, you have to really have to want that,” Welch says.

“And the payoff is huge,” Laura Rozza adds.

Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority

Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority

Photo: Navajo Tribal Utility Authority

For Julia Rosenblatt, the solution to affordable housing was to move in with friends and family—more than 10 people under one roof.

For Julia Rosenblatt, the solution to affordable housing was to move in with friends and family—more than 10 people under one roof. Shirlene Stoven, 81, organized her fellow senior housing residents in the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, and formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative. They fended off developers and were able to work with the city and nonprofits to buy the land their homes sit on. Photo by Austen Diamond.

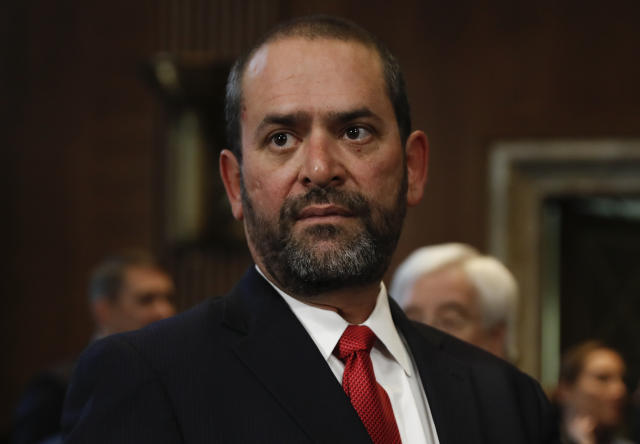

Shirlene Stoven, 81, organized her fellow senior housing residents in the Applewood mobile home park in Midvale, Utah, and formed Applewood Homeowners Cooperative. They fended off developers and were able to work with the city and nonprofits to buy the land their homes sit on. Photo by Austen Diamond. January 19, 2017 photo: Jeff Miller attends then Energy Secretary-designate Rick Perry’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on Capitol Hill in Washington. President Donald Trump has talked frequently about ‘draining the swamp’ of inside dealers in Washington. But lobbyist Jeff Miller might be considered part of the new swamp. Miller, who is a close friend of Energy Secretary Rick Perry, is pushing the administration for a bailout worth billions of dollars for FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt coal and nuclear power company. Miller has earned $3.2 million in just over a year as a lobbyist for clients that include several large energy companies. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

January 19, 2017 photo: Jeff Miller attends then Energy Secretary-designate Rick Perry’s confirmation hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on Capitol Hill in Washington. President Donald Trump has talked frequently about ‘draining the swamp’ of inside dealers in Washington. But lobbyist Jeff Miller might be considered part of the new swamp. Miller, who is a close friend of Energy Secretary Rick Perry, is pushing the administration for a bailout worth billions of dollars for FirstEnergy Solutions, a bankrupt coal and nuclear power company. Miller has earned $3.2 million in just over a year as a lobbyist for clients that include several large energy companies. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster) In this May 21, 2018 photo, a barn that can hold up to 4,800 hogs sits at the Will-O-Bett Farm outside Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the hog operation have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a barn that can hold up to 4,800 hogs sits at the Will-O-Bett Farm outside Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the hog operation have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo In this May 21, 2018 photo, a sign opposing an industrial hog farm is displayed at a home in Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the nearby hog farm have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo

In this May 21, 2018 photo, a sign opposing an industrial hog farm is displayed at a home in Berwick, Pa. Residents who complain about foul smells from the nearby hog farm have taken their fight to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Michael Rubinkam AP Photo Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt testifies before the house Energy and Commerce Committee’s environmental subcommittee in the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill April 26, 2018 in Washington, D.C. The focus of nearly a dozen federal inquiries into his travel expenses, security practices and other issues, Pruitt testified about his agency’s FY 2019 budget proposal. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt testifies before the house Energy and Commerce Committee’s environmental subcommittee in the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill April 26, 2018 in Washington, D.C. The focus of nearly a dozen federal inquiries into his travel expenses, security practices and other issues, Pruitt testified about his agency’s FY 2019 budget proposal. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.