EcoWatch

November 28, 2018

Air pollution is now more deadly than war, smoking and TB

Posted by EcoWatch on Tuesday, November 27, 2018

Read About The Tarbaby Story under the Category: About the Tarbaby Blog

November 28, 2018

Air pollution is now more deadly than war, smoking and TB

Posted by EcoWatch on Tuesday, November 27, 2018

Amazon Rainforest deforestation has hit its highest rate in 10 years. 3,050 square miles of forest cleared between August 2017 and July 2018.

Please let your friends and family know…See More

Brazil lost 1 million football pitches worth of forest in a single year

Amazon Rainforest deforestation has hit its highest rate in 10 years.🌎 https://bit.ly/2TUDfPj

Posted by EcoWatch on Friday, November 30, 2018

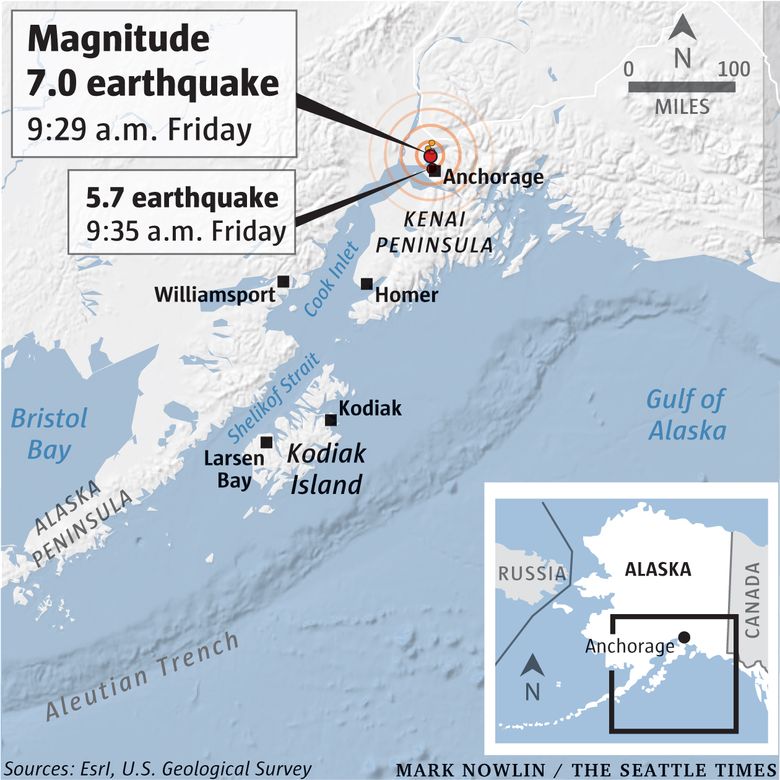

What we know about the quake: A 7.0-magnitude earthquake rocked buildings in Anchorage Friday morning. Officials issued a tsunami warning for southern Alaska coastal areas of Cook’s Inlet and part of the Kenai peninsula.

10:37 a.m.: The Anchorage school district told parents that all students were safe following the earthquake, according to the Anchorage Daily News.

10:27 a.m.: People on social media are posting video and photos showing reported damage in the Anchorage area.

10:20 a.m. The United States Geological Survey is now listing the earthquake as a 7.0-magnitude shaking, according to its website.

10:10 a.m. A 6.6 magnitude earthquake shook Anchorage Friday morning. The Associated Press reports the shaking caused lamp posts and trees to sway, prompted people to run from offices and seek shelter under desks.

Officials issued a tsunami warning for southern Alaska coastal areas of Cook’s Inlet and part of the Kenai peninsula.

Associated Press November 30, 2018

An Associated Press reporter working in downtown Anchorage saw cracks in a 2-story building after the quake. It was unclear whether there were injuries.

People went back inside buildings after the earthquake but a smaller aftershock a short time later sent them running back into the streets again.

Shortly after the quake, a tsunami warning was issued for the southern Alaska coastal areas of Cook’s Inlet and part of the Kenai peninsula.

The warning means tsunami waves were expected.

The U.S. Geological Survey initially said it was a 6.7 magnitude earthquake and then reduced the magnitude to 6.6.

Our nation’s leading political news programs routinely host propagandists to spread nonsense about climate change.

By Jack Holmes November 28, 2018

Rarely do you get news of an ongoing catastrophe and, within a couple of days, a perfect example of why we’ve done nothing about that exact problem. But Chuck Todd and Meet The Press were happy to oblige this Thanksgiving weekend. On Friday, the Trump administration attempted to bury a harrowing U.S. government climate-change report by releasing it on Black Friday, a notorious dumping ground for bad news. Normally, though, the bad news is just for the current administration—not the whole world.

On Sunday, Todd hosted Danielle Pletka of the American Enterprise Institute on his teevee show. Her performance—and it was a performance—was a shining example of how the ruling class has successfully hemmed and hawed for decades, with the full support of the feckless Beltway media, slowing any kind of action and safeguarding big-business profits while experts in the field have known full well that human civilization as we know it is in clear and escalating peril.

As Pletka so happily volunteered, she is not a scientist. So why was she invited on one of the nation’s Premier Political Talk Shows to spread disinformation about a scientific issue? That two years since 1980 have been cold does not have any bearing on the scientific consensus that climate change is real and man-made. This member of the conservative intelligentsia—the American Enterprise Institute, for which Pletka works, is a right-wing “think tank”—is actually just making the more polite version of President Good Brain’s argument on Wednesday.

This is not the first time Trump has disproved global warming on the basis he is cold today. (Elsewhere, he has simply called it a Chinese hoax.) Nobody put this crap to bed better than Stephen Colbert did all those years ago. Weather is not climate. The weather is affected by changing climate patterns, but warming global temperatures over the decades—an indisputable trend, even among denialist hacks like Pletka—does not mean every day of every year will be warmer than the previous. What it does very likely mean is more powerful storms that drop trillions of gallons of water on American cities, and bigger, more ferocious wildfires that turn the American West to ash.

Of course, Pletka probably knows this. She gave Our Beautiful Boy Chuck Todd that tried-and-true conservative line that’s rapidly going stale: that surely something is happening with the climate, but who can say whether humans are causing it? Well, after years of exhaustive study, scientists have found it is “extremely likely” (terms the scientific community does not choose lightly) that humans are significantly contributing to warming global temperatures. We also know that the Beautiful, Clean Coal that Pletka suggested the U.S. has switched to does not exist. “Clean coal” is a misleading term for the same coal that continues to be the dirtiest fossil fuel in existence.

Did Todd challenge her with the facts? No. But this is what the evidence says. It’s just Pletka isn’t concerned with gathering the evidence and coming to a conclusion—also known as the essence of the scientific method. Here is an (albeit anonymous) account from an Atlantic reader who claims to have worked for Pletka at the American Enterprise Institute:

A number of years ago I worked for Danielle Pletka for a summer as a researcher, and her piece today matches the “scholarship” she and AEI were producing in the early part of this decade. I was rarely if ever asked to perform background research on a subject but was more often asked to provide specific evidence to support ready made assertations. At the time AEI was mobilizing in support of military action against Iraq, and it was quite clear to me that the academic process was reversed – positions designed, research dug up to support the positions.

This seems like an opportune moment to mention that Pletka is widely known as a varsity-level cheerleader for the Iraq War. More recently, she demonstrated her intricate knowledge of the conflict by suggesting to the French ambassador on Twitter that France had joined the U.S. in the conflict. OK, so that was completely and laughably wrong (Remember the idiotic Freedom Fries charade?), but at least by 2013 she was…still defending the invasion. Yes, after it embroiled the region in sectarian conflict, and after all the reasons people like Pletka peddled for going in were proven to be baseless. Eventually, this genius foreign-policy move led to the rise of ISIS. This is just another example of how, if you work in the Beltway, there are absolutely zero consequences for being completely wrong about everything.

In fact, if you work at a think tank like AEI, it might just get you a raise—if you stick to the party line. All think tanks are, to some extent, mouthpieces for their donors, but that particularly goes for a right-wing gun-for-hire shop like the Institute. The Guardian uncovered how AEI works to undermine the science on climate change in 2007:

Scientists and economists have been offered $10,000 each by a lobby group funded by one of the world’s largest oil companies to undermine a major climate change report due to be published today.

Letters sent by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), an ExxonMobil-funded thinktank with close links to the Bush administration, offered the payments for articles that emphasise the shortcomings of a report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Travel expenses and additional payments were also offered.

And what did that ExxonMobil funding look like?

The AEI has received more than $1.6m from ExxonMobil and more than 20 of its staff have worked as consultants to the Bush administration. Lee Raymond, a former head of ExxonMobil, is the vice-chairman of AEI’s board of trustees.

You may remember that Exxon was also exposed as having discovered, through the work of its own scientists, that climate change was real as early as 1977. Instead of accepting this reality and beginning the work of responding to the burgeoning climate crisis, Exxon chose to fund disinformation on the topic for decades, protecting their profits in the shorter term. They’re not alone among oil-and-gas outfits, many of which simultaneously started building their rigs to accommodate sea-level rise that would result from the climate change that, in public, they steadfastly disputed was happening.

One way to fund disinformation is to pay a think tank like AEI to spread it for you. And that’s what Pletka was still doing, on Sunday, after just the latest report dropped detailing the catastrophic consequences of our inaction on the climate crisis. The U.S. report focused on the fact that the crisis will melt 10 percent of the American economy and send it crashing into the ocean by 2100. Farmers in the midwest will lose 75 percent of the crop yield on their corn. Rising sea levels will put trillions of dollars in coastal real estate in jeopardy. But last month’s report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—compiled by 91 leading scientists from 40 different countries based on more than 6,000 scientific studies conducted by still more scientists—was even more apocalyptic. It found that human civilization as we know it will be in severe peril by 2040, and that we have 12 years to dramatically change course to avoid that scenario.

Amid all that, news programs like Chuck Todd’s Meet The Press—offerings that putatively exist to inform the public about the world around them—are still playing host to people who are paid to spread false information about the world. Todd is not alone: CNN hosted Rick Santorum on Sunday. Like NBC News, which employs Pletka as a contributor, they pay Rick directly to spread nonsense.

This festering boil on the body politic highlights another in-vogue conservative argument: that the scientists who’ve devoted their lives to studying the climate are really just in it for those juicy government grants to continue studying it. It’s all about the money! As usual in this era, this is a case of accusing the opposition of something you’re already up to.

Santorum is applying the incentive structure that exists for massive multinational oil and gas corporations and those they employ—seeking out certain findings because you have a vested financial interest in a certain outcome—to climate scientists. In reality, the kind of conspiracy that right-wingers like Santorum are alleging here would be perhaps unprecedented in scale. If this is all a big con, thousands of climate scientists spread across dozens of countries would need to all be getting their kickbacks, and have a way to secretly stay on-message. It’s absurdly unlikely, and it belies the aforementioned way that the scientific community vets a scientific report’s findings.

Oh, and the money in government grants ain’t actually that good. That’s why some “scientists” might take, say, $10,000 from AEI to dispute the scientific consensus. It’s all bullshit, folks, and it’s bad for ya.

All this is to say that the nation’s major television news stations routinely play host to propagandists who are paid, directly or indirectly, to spread disinformation and muddy the waters to protect the interests of massive energy corporations, all at the expense of the future of human civilization.

When Pletka said emissions are down since President Trump withdrew from the Paris climate accords—making the U.S. the only nation in the world that refuses to participate—that was just true enough: they are down in 2018, though the rate of emissions reductions slowed from the previous two years and will likely continue to slow as the Trump administration attempts to roll back our efforts to combat the crisis. The crown jewel in that regard is the Clean Power Plan, our main vehicle for meeting our obligations under the Paris agreement, which Trump has sought to repeal. At the very least, Todd is obligated to challenge this crap if he’s going to host a dishonest broker—or host someone who can. According to John Whitehouse of MediaMatters, none of the Sunday Shows hosted a single scientist while covering the climate in 2016 and 2017.

The Meet The Press chief will certainly defend his decision to host a climate-change “skeptic” on the basis of “intellectual diversity” and Hearing From Both Sides, as if what his viewers need is to hear both the truth and utter nonsense. Both Sides are not operating in good faith here. One side accepts the scientific consensus. On the other, the Republican Party is the only major political party in the industrialized world that disputes it. Both Sides Journalism, which falsely equates the truth about the world we’ve determined through the scientific method with self-serving crap dished out by the instruments of oil interests, has made it politically palatable to do nothing, for decades, about an existential threat to humanity. Friday’s report further underlined the crisis facing humankind. Two days later, Meet The Press showcased part of how we’ve allowed things to get to this point.

But since we’re on the topic of intellectual diversity, here’s a suggestion: If Chuck Todd wants to talk about a scientific topic, how about having a fucking scientist on?

France taking steps to fight ‘imported deforestation’!

Read more ➡️ Ecowatch.com/france-palm-oil-deforestation

France will cut imports of palm oil, soy and beef to fight ‘imported deforestation’

France taking steps to fight 'imported deforestation'! Read more ➡️ Ecowatch.com/france-palm-oil-deforestationvia World Economic Forum

Posted by EcoWatch on Thursday, November 22, 2018

More than half of Arizona’s farms are run by Native Americans, and they’re now poised to scale up centuries-old sustainable practices to tap into global trade.

By Tayler Brown, Agroecology, Indigenous Foodways – November 21, 2018

Thirty miles south of Phoenix, green fields of alfalfa and pima cotton stretch toward a triple-digit sun. Hundreds of yellow butterflies dance above the purple flowers that dapple the tops of the young alfalfa stalks—to expert eyes, the flowers signal that the plants are heat-stressed and should be harvested soon.

Gila River Farms near Sacaton has been growing alfalfa and high-end cotton—which is named after the Pima people who inhabited the Gila and Salt river valleys—for 50 years. That’s a long time by current standards but merely a flash considering that the roots of Arizona’s agriculture reach back thousands of years.

A Gila River Farms worker harvests alfalfa, a main cash crop. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

A Gila River Farms worker harvests alfalfa, a main cash crop. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

Today, Native Americans are the primary operators of more than half of all farms or ranches in the state, making Arizona’s agriculture landscape unique compared with other states, according to the 2014 national agriculture census. Native American farmers sold nearly $67 million worth of agricultural products in 2012, about 2 percent of the $3.7 billion in agricultural products sold in Arizona that year, according to the Arizona Farm Bureau.

Native American farmers grow crops as diverse as tepary beans, olives, and squash, some for community use and some sent around the world. The Navajo and Hopi tribes feed their communities by focusing on cultural traditions, including dryland farming.

Stephanie Sauceda, interim general manager for Gila River Farms, said the farm is the original test site funded by the federal government to grow and harvest extra-long staple pima cotton, which is considered a superior strain.

Farming extends back centuries for indigenous people, she said.

“It was just something that Native American people do, not only in Gila River, but also in other tribes. That’s how we survived,” Sauceda said. “We did the hunting of the animals, we grew our corn and our wheat, and that’s how we actually survived—how our ancestors survived.”

The natural next step, she said, is to send crops to the rest of the world.

Gila River Farms primarily grows cotton and alfalfa but in recent years has branched out to increase citrus production and experiment with olive crops, said Garcia, the farm’s assistant general manager.

Gila River Farms will celebrate its 50th anniversary this year. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

Gila River Farms will celebrate its 50th anniversary this year. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

Sauceda said alfalfa and cotton, which are the farm’s most profitable products, end up in such places as the Philippines, Vietnam and China.

“We represent the community with our products that go out the door,” said Sauceda, who’s only the second woman to be general manager. She and her employees take pride in being able to bring their product into the global market.

“We have a really good name out there.”

The farm is growing crops on 10,000 acres, rotating alfalfa and cotton on much of that land, Sauceda said. It generates about $10 million annually.

In northern Arizona, members of the Hopi Tribe maintain their cultural and traditional heritage through farming, said Michael Kotutwa Johnson, a Hopi doctoral candidate at the University of Arizona’s School of Renewable Natural Resources and the Environment.

“For Hopi, farming is our way of life,” Johnson said.

Hopi farmers own small plots of 1 to 9 acres and use the traditional technique of dryland farming, which means crops rely only rainfall, Johnson said. Dryland farming requires seeds be planted deeper than crops for commercial use, he said.

Hopi agriculture largely is subsistence-based, meaning farmers grow food for their families rather than for commercial sale, Johnson said.

One hundred miles south of where the four corners of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado meet, three members of the Navajo Nation lead a biweekly farm-board meeting.

The two women and one man conduct the meeting in both English and Diné to be sure the older generation can understand policy changes and upcoming projects.

The farm board discusses a five-year project to update fencing, irrigation and farm equipment.

On the Navajo Reservation, farming and ranching work hand-in-hand, said Lorena Eldridge, farm board president of the tribe’s Tsaile Wheatfields-Black Rock Chapter.

Lorena Eldridge, farm board president for the Tsaile Wheatfields-Black Rock Chapter on the Navajo Reservation, explains how the irrigation systems have been updated in recent years. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

Lorena Eldridge, farm board president for the Tsaile Wheatfields-Black Rock Chapter on the Navajo Reservation, explains how the irrigation systems have been updated in recent years. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

Navajo farmers differentiate themselves from most U.S. farms in a key way: Nearly half of all farms on the reservation are operated primarily by a woman, Eldridge said.

According to the 2012 agriculture census, women represent about 30 percent of the total number of American farmers, but only 14 percent of farms are operated by a woman.

Still, younger generations are moving away from farming on reservations.

One third of all Native American farmers are older than 65. Eldridge is working to secure investments from the Navajo Nation government to attract younger people to farming. The farm board secured $5 million for the five-year project, which will complete its first year in December.

“For me, the farm board connects me to my history and culture,” Eldridge said.

Some Native American farmers carry on crop-based traditions, whether for commercial or community uses.

Blue corn, beans, and traditional teas and berries, such as greenthread tea and sumac berries, are grown on Native American farms across Arizona.

Ramona and Terry Button pulled the native bavi bean, commonly referred to as the tepary bean, from the brink of obscurity in the late 1970s, said Velvet Button, their daughter.

Gila River Farms recently planted olive trees on several acres, which should be ready for harvest this year, said Hector Garcia, assistant general manager. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

Gila River Farms recently planted olive trees on several acres, which should be ready for harvest this year, said Hector Garcia, assistant general manager. (Photo By Tayler Brown/Cronkite News)

Drought had put many other local farmers out of business, but Ramona Farms on the Gila River Reservation survived, in part based on reclaiming a bean that had been around for centuries.

Native American communities had “lost touch” with the tepary bean and other traditional native foods, Velvet Button said.

“We lost our market when large grocery stores moved in closer to the reservations and took over the mom and pop shops that were servicing the rural communities,” she said.

The tepary bean comes in black, white, blue speckled, and other colors, Button said, and is an important staple food for several tribes.

Ramona Farms, family owned and operated, generates 90 percent of its income from such commercial crops as cotton, wheat and alfalfa, but the Button family’s passion is promoting and educating people about indigenous foods.

Water scarcity, the proliferation of grocery stores and a lack of agriculture education and policy have been hurdles to food sovereignty that organizations such as the Indigenous Food Systems Network and the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance are working to overcome.

“The huge food sovereignty movement has helped connect us once again as indigenous communities and our traditional food sources,” Button said. “Our communities are so remote that we need to be able to sustain ourselves.”

According to 2016 data published by the Arizona Department of Health Services, American Indians are disproportionately affected by chronic diseases, such as diabetes. Native Americans die at three times the rate to diabetes compared with the state’s average the report said.

Refocusing on traditional foods and incorporating them in new recipes has been a stepping stone to improving the community’s health education, Button said.

“When you see the community growing their own food, being involved in the process—it really makes a difference,” Johnson said. “When you give people access to this, you see rates of diabetes going down and you see everyone’s well-being going up.”

This article originally appeared on Cronkite News and is reprinted with permission.

For more stories from Cronkite News, visit cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Cronkite News, the news arm of Arizona PBS, is operated by Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communications and staffed by students of the school.

With the help of nonprofits and land trusts, young farmers are staking out the space to change the face of America’s farmland.

By Tom Perkins, Farm Labor and Policy, Local Eats November 20, 2018

It’s rare to see Lorenzen and White’s demographic taking over land. Because retiring farmers need income to sustain them through their later years, they often sell to developers or to large corporate or expanding family farms at a price that small farmers can’t afford, says Neil Thapar, an attorney with the Sustainable Economies Law Center.

“They don’t have a safety net for retirement, but from their farming career they have assets, land, equipment. They can’t sell that to next-generation farmers because [the next generation] doesn’t have access to the kind of capital they need to buy at $7,000 per acre,” he says.

That scenario is the driving force behind a steady consolidation of the nation’s farmland. A USDA report published in March found that large farms own more of the nation’s farmland compared to a few decades ago. In 1987, farms with over 2,000 acres operated 15 percent of the nation’s farmland; by 2012, that number had grown to 36 percent.

“If we don’t do something now to offer new options and new tools, all we are going to see is consolidation,” says SILT director Suzan Erem. “People tend to go with what they know. What’s out there is ‘I grow corn, my neighbor grows corn, so my land will go to my neighbor.’ So that 10,000-acre guy just went to 10,500.”

The USDA report noted that consolidation is also happening through contract farming, as large corporate firms play a coordination role in U.S. farming, particularly in hog and poultry production. Some firms—for example, in specialty crops, cattle feedlots, poultry, and hogs—operate multiple farms.

But there’s also the concern, voiced by The Oakland Institute and others, that huge investors and pension funds, such as TIAA-CREF, the Hancock Agricultural Investment Group (HAIG), and UBS Agrivest—an arm of the bank’s global real estate division—have a bottomless appetite for farmland, purchasing up parcels and adding to a lack of access and affordability.

“Over the next 20 years, 400 million acres, or nearly half of all U.S. farmland, is set to change hands as the current generation retires. With an estimated $10 billion in capital already looking for access to U.S. farmland, institutional investors openly hope to expand their holdings as this retirement bulge takes place,” according to the Institute’s 2014 report, “Down on the Farm: Wall Street: America’s New Farmer.”

The farmland-conservation advocacy group American Farmland Trust echoes this concern. The group notes that people over 65 years old own 40 percent of the nation’s farmland, and a major transfer of the agricultural land and wealth is afoot. As of now, large farms are scooping up most of that property, raising questions of what that means for the average food consumer and the small farmer.

The uncertainty that situation creates is compounded by the expiration of the 2014 Farm Bill at the end of September. Negotiations for a new farm bill are underway, but it’s unclear what it may hold for funding for some of the most effective measures in place to slow consolidation. Depending on whether the version passed by the House or the Senate—or some combination of two—is approved, funding for conservation efforts like those that are part of the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) may double or be eliminated. ACEP provides money for state and local agencies to “buy-protect-sell” farmland, which is one of the most effective tools available in preserving farmland and preventing further consolidation.

Meanwhile, a growing number of nonprofits and land trusts like SILT are using a combination of agricultural conservation easements and other measures to reduce the cost of land to make it accessible to the next generation of farmers.

The face of that generation is increasingly diverse, according to Julia Freedgood, assistant vice president of programs at American Farmland Trust.

Freedgood works with a nationwide network of ag-industry people who are developing a curriculum to teach new farmers financial skills. The old saying that the only route into farming is “through the cradle or altar” is less true these days, as more immigrants and refugees want to start farms in places like Idaho, she says. In California, many Latinx and Hmong farmworkers want their own land. So do young, college-educated people “inspired by the local food movement,” and city-dwellers inspired by the urban ag movement.

“You have this really diverse group that wants to get into farming, but they all face the barrier of land access,” Freedgood says.

Land consolidation is tied to power and control—it puts the wealth generated by the nation’s agriculture industry into fewer hands. This directly impacts accessibility: what and how most Americans will eat. Ultimately, the issue is structural, and opportunities for meaningful change lie in addressing the needs of retiring farmers and those entering the industry.

“It gets at the core of our economic system and challenges the notion of capitalism as the way to organize our food economy,” Thapar says. “The consolidation trend will continue until there are significant reforms on how people access capital to acquire land, and how farming can become a livelihood that people can rely on without having to sell land to retire.”

Thapar notes that change needs to happen at a policy level. The good news is that there is a patchwork of laws and funding at the state and federal level to help create that change; the bad news is that the patchwork is patchy—farmers in different states face very different options for financial support.

The federal government hasn’t enacted any sort of meaningful legislation or rules that protect and promote small-scale farming—most recently, Obama pledged and failed to do so during his presidency. The standardization that comes with commodity stock production also over time made it easier for farms to consolidate, leaving fewer operators with greater influence on policy decisions designed to promote commodity stock production. That’s helped lead to the creation of crop insurance and commodity-linked direct payments programs, for example.

A patchwork of laws and state and federal funding that helps address the situation. At the federal level, the farm bill provides $31 million for farmland preservation, but that money is often targeted for cuts by Republicans and lobbyists for big business. In Minnesota, the state provides tax breaks for those who sell or lease equipment to small farmers. Rhode Island launched a program in which it buys farmland from retiring landowners, then sells it to young or new farmers for below-market rate.

Freedgood has worked to enact easement programs in Ohio and Michigan, and is attempting to do the same in other Midwestern states such as Indiana (though she says it doesn’t currently have the “political will”). She also points to state-level programs like California Farm Link and Hudson Valley Farmland Finder, which are “actively working with agriculture service providers and land trusts, and are the brokers to help make deals happen.”

Offering capital gains tax breaks to retiring farmers who sell to younger farmers could be a strong incentive because “it can make a significant difference in the net bottom line,” says Jerry Cosgrove, farm legacy director with AFT.

Thapar suggests a pension program that provides annuity payments to independent farmers so they don’t have to rely on land and asset sales to pay for their retirement.

Land trusts are offering “measures to address what can broadly be called land access and affordability issues, particularly for young or other socially disadvantaged farmers,” Cosgrove says.

The measures can be complicated, but they’re working. Cosgrove says AFT helped Zack and Annie Metzger—who are in their mid-30’s—purchase land from a retiring farmer in Troy, N.Y. The land held a conservation easement and affordability deed restriction, and its owner asked for over $650,000. The Metzgers decided to sell the easement and deed restriction to raise capital, but couldn’t do so until they owned the property. That required a bridge loan through Equity Trust. The sales of the easement and affordability deed helped pay off that loan.

The Metzgers sold the deed restriction to a local nonprofit conservation group that holds it and is obligated to enforce its terms. The state of New York provided the funding for the nonprofit to purchase easement, and it can only be sold to a nonprofit or municipality.

“We’re privileged people, we come from a great background, but not to where we have the wealth to purchase a property … with an appraised value [of around $650,000],” Zack Metzger said. On Laughing Earth Farm, the Metzgers now offer humanely and organically raised pigs, chickens, and turkey. Laughing Earth’s vegetables go to local CSAs, and they sell freshly cut wildflowers at farmers’ markets.

AFT typically purchases land or takes a land donation, puts it in an easement, seeks an affordability deed restriction, then leases the land long-term to a younger farmer. So far, about 6.5 million acres of farm and ranch land are preserved in land trusts, according to a 2017 survey conducted by AFT, which the agency says is a conservative estimate. That’s up from about 4.7 million in 2012.

In Iowa, SILT uses a similar strategy. The owner of the land on which Jupiter Ridge operates donated his deed to SILT because he’s interested in preserving it for sustainable food farming. When he decides he no longer wants to control the land (or he dies), White and Lorenzen will enter into a long-term lease with SILT. They can also own the land’s home and other buildings, and they can pass it on to younger farmers or their kids when they’re ready to retire, or SILT will place a conservation easement on the land if for some reason they must sell. Either way, the land is preserved for sustainable farming in perpetuity.

Jupiter Ridge represents 22 of 770 acres under SILT’s protection, and Erem expects that number to grow quickly.

In New Hampshire, Agrarian Trust, a nonprofit group working to increase land access for farmers, will soon begin purchasing land. It’s partnering with local land trusts that will own the properties, acquire a conservation easement, and function as a “farm commons” that will manage a 99-year lease with a young farmer. Agrarian Trust will support and have some level of controlling interest over the local nonprofit. It’s partly focusing on regions in which there is little in the way of agricultural conservation efforts, like the Southeast.

Poudre Valley Community Farms in Colorado is using a slightly different model. The group just made its first purchase: a 109-acre farm with a five-bedroom house, corrals, and outbuildings for $1.3 million. Poudre Valley is controlled by a multi-stakeholder cooperative that board member Zia Zybko characterizes as “truly community supported”—if the farm has a problem, the cross-section of the community that invested in the farm works together to find a solution.

Ultimately, it’s going to take a coordinated effort at the federal level and among those working at the local level, instead of a patchwork of independent agencies operating toward a similar goal Thapar says. “There are some systemic changes that need to happen, and there needs to be a broader coalition working on this,” he notes. Specifically, he suggests reviving the USDA AELOS survey that retrieves landowner information and demographics, farmland rent control policies, re-funding federal and state land preservation programs, promoting state-based land ownership surveys, and providing reliable funding mechanisms for land trusts and land cooperatives.

But beyond that, Thapar says, there needs a collective philosophical shift away from land being viewed as a “financial asset—something that you own to make money from in the future.”

Chef Rob Kinneen’s web series ‘Fresh Alaska’ promotes fresh, local ingredients from even the remotest parts of his home state.

Raised mainly in Anchorage Alaska, where produce can be hard to find and often very expensive, Kinneen wasn’t exposed to much in the way of fresh fruits or vegetables. His connection to food, however, was always there.

“There was still an affinity with the land and with food,” he says. “We harvested a lot of seafood, we hunted, we went clam-digging.” He remembers his mom baking fresh bread and picking fresh rhubarb and eating it raw, dipped in sugar. And when his dad grew potatoes for the first time, Kinneen helped him harvest them. “We boiled them and ate some that same day, and I remember how earthy they tasted,” he recalls.

These memories, coupled with a desire to connect with his Tlingit heritage, led to an interest in cooking with locally sourced, indigenous Alaskan foods.

After attending CIA, and working in restaurants in New Orleans, Los Angeles, and North Carolina, Kinneen made his way back to Anchorage, where he lived and worked for 15 years. To be closer to extended family, he and his family recently relocated to North Carolina, where he serves as executive chef for both Happy Cardinal Catering and the Italian restaurant The Boot. And he travels back to Alaska regularly and still considers it “home.”

“Getting married and having children helped me realize I needed to know more about my own Alaskan heritage,” says Kinneen.

The result is “Fresh Alaska” and “Traditional Foods, Contemporary Chef,” two web series that show him traveling around Alaska, harvesting and cooking traditional native foods. On screen, Kinneen can be seen doing things like collecting sea cucumber in Sitka, eating salmon berry flowers, catching shrimp in Prince William Sound, cooking with reindeer sausage, and picking berries to make Akutaq (the traditional Alaska Native version of ice cream). He partnered with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) to produce both series.

Rob Kinneen cooking with one of the health educators at the Southcentral Foundation as part of his “Fresh Alaska” web series.

Rob Kinneen cooking with one of the health educators at the Southcentral Foundation as part of his “Fresh Alaska” web series.

Kinneen’s series give his audience the chance to see how local foods can be prepared at minimal cost. “Making these videos helped show what food means in different regions of the community,” he says. “It also inspired me to consider how people are finding answers to food sustainability.”

As part of his work, he visited places like Tyonek, Alaska, southwest of Anchorage; the town’s conservation district recently spent a million dollars to build a culvert over a salmon stream to help the fish migrate. Kinneen saw firsthand how the Tyonek Tribal Conservation District has worked to take back health and wellness in the community through sustainability, with programs such as the “seed start” program at the local school.

“They have a greenhouse and an irrigation system that is set up with a solar generator,” he says. “Solar panels have a life of 30 years, which makes them much more viable than using a regular generator and diesel fuel.”

The solar-powered generator to irrigate Tyonek’s community garden. (Photo courtesy of Rob Kinneen)

The solar-powered generator to irrigate Tyonek’s community garden. (Photo courtesy of Rob Kinneen)

He also visited Meyers Farm in Bethel, where owner Tim Meyer has created a successful organic farming community in far western Alaska, producing hundreds of pounds of produce each season.

“Ninety-six percent of the food in Alaska is imported, which leads to questions about food security,” says Kinneen. “Tim Meyer is growing produce on the tundra. He uses cold-climate farming techniques and grows on a nutrient-rich riverbed. The produce is preserved in an underground cellar with a drip oil pan stove that keeps temperatures at about 34 degrees. If you can successfully grow vegetables in a place like Bethel, I think you can do it almost anywhere.”

Grocery stores in the more remote areas are especially poorly stocked. “It’s not unusual to see a $19.00 fermented [i.e., old] pineapple or a $9.00 head of brown iceberg lettuce for,” says Kinneen. For this reason, making fresh and natural food accessible to all people has also become a passion project for Kinneen, and he has partnered with groups like the Food Bank of Alaska to highlight how Alaskans can use the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) dollars (or “food stamps”) at farmers’ markets.

With one in seven people in the state considered food-insecure, and access to SNAP threatened in negotiations over the current farm bill, helping people eat nutritious, local food whenever possible is more important than ever. And Alaska’s remote geography often means that its communities face additional obstacles in accessing resources, and thus they must rely on wild foods to fill the gaps.

Roasted salmon served on a bed of Tyonek-grown vegetables; only the salt, pepper, and oil came from outside of Alaska. (Photo courtesy of Rob Kinneen)

Roasted salmon served on a bed of Tyonek-grown vegetables; only the salt, pepper, and oil came from outside of Alaska. (Photo courtesy of Rob Kinneen)

Kinneen’s work has culminated in his new cookbook, Fresh Alaska. The recipes, such as arctic polenta with razor clams, combine contemporary, upscale cooking with traditional Alaskan food. It’s a big step for Alaska cookbooks, despite the fact that chefs in high-end restaurants around the state have been incorporating indigenous ingredients such as foraged mushrooms, spruce tips, and locally caught seafood in recent years.

“My main beef with Alaskan cookbooks is that they are either very esoteric or they don’t contain Alaskan ingredients,” he says. “I wanted to promote the people and places I came from, with insight into the subsistence side, [while] also being responsible as a chef.”

While Kinneen and his family enjoy their life in North Carolina, his Alaskan roots are never far from his mind. “The experiences I had at places like Meyers Farm and Tyonek were a huge inspiration for my cookbook,” he says. “To see the efforts of a small village to take back food sustainability and prosper is truly humbling. Food is the connection between all of us.”