What.If shared a Video

January 30, 2019

If the force of gravity disappeared, floating off into space would be the least of your worries.

What If Gravity Suddenly Went Away?

Posted by What.If on Monday, March 19, 2018

Read About The Tarbaby Story under the Category: About the Tarbaby Blog

January 30, 2019

If the force of gravity disappeared, floating off into space would be the least of your worries.

What If Gravity Suddenly Went Away?

Posted by What.If on Monday, March 19, 2018

✨Inspiring & Easy Way to Make a Huge Difference #LandfillChallenge ✨

We challenged you to hold on to your trash for 21 days! Here’s the results of that challenge in an informing live talk show.

Also, we will be announcing the date of the next challenge! Stay tuned.

✨Inspiring & Easy Way to Make a Huge Difference #LandfillChallenge ✨We challenged you to hold on to your trash for 21 days! Here's the results of that challenge in an informing live talk show.Also, we will be announcing the date of the next challenge! Stay tuned.

Posted by EcoWatch on Saturday, January 26, 2019

Including the world’s first bike path made from recycled plastic.

Here are 3 innovative ways the Netherlands is creating a society where nothing goes to waste

Including the world's first bike path made from recycled plastic. World Economic Forum

Posted by EcoWatch on Friday, January 25, 2019

‘We have changed the world so much that scientists say we are now in a new geological age, the Anthropocene – the Age of Humans.’

David Attenborough says 'The Garden of Eden is no more'

‘We have changed the world so much that scientists say we are now in a new geological age, the Anthropocene – the Age of Humans.’World Economic Forum #wef19

Posted by EcoWatch on Thursday, January 24, 2019

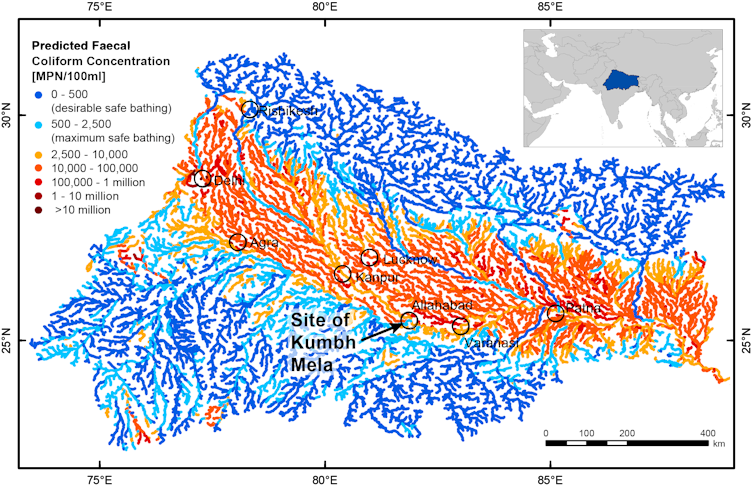

The Ganges is a lifeline for millions of people who live within its catchment as a source of water, transport and food. During the Hindu pilgrimage known as Kumbh Mela the Ganges plays host to the largest human gathering on Earth as 120 m people arrive to bathe in the river over 49 days.

Despite its tremendous spiritual significance, the Ganges is also notorious for having some of the most polluted water in the world. For 79% of the population of the Ganges catchment, their nearest river fails sewage pollution standards for crop irrigation. Some 85% of the population live near water that isn’t safe for bathing and Allahabad – where Kumbh Mela takes place in 2019 – is one of those places.

Our own research suggests that as the number of people living in nearby cities increases, the problem with water quality in the Ganges worsens. Urban populations in the Ganges catchment contribute around 100 times more microbial pollution per head to the river than their rural counterparts. This means that untreated sewage discharged from a sewer appears worse for river water quality than sewage discharge where there are no sewers at all.

When we examined 10 years of water quality data we found that the concentration of fecal coli forms – a common pollution indicator found in human feces – increased when the density of people living upstream increased. This makes sense: more people means more poo.

But we also found that people living in cities in India contribute more pollution per person than those in rural areas – how much more depends on the population density. A person living in an area in India with 1,000 people per km², a density similar to central London, contributes on average 100 times more pollution to the nearest river than they would in an area with 100 people per km² – say, rural Devon in the UK.

So why does it appear that a person living in an Indian city produces more sewage pollution than someone living in the countryside?

Of course, people in the cities are unlikely to actually contribute significantly more feces than those in rural communities. Instead, it’s probably sewers that are to blame. In cities, extensive sewage networks efficiently flush sewage to the river, whereas in rural areas more people defecate in the open or in pit latrines. This means feces in rural areas are less likely to be washed into the river and the bacteria and viruses they carry are more likely to die in situ.

As the population density of a place increases, sewers become more common. Sewage removal is essential for the protection of public health, but without effective treatment, as is typically the case in the Ganges catchment, it comes at the cost of increased river pollution and waterborne diseases for people living downstream.

It’s therefore clear that water quality in the Ganges is a more complex and widespread problem than previously thought. We’d expected that cities, with their more advanced sewage management, would be better for the river. What we found was the opposite – more sewers without sewage treatment makes river pollution worse.

The urgency to invest, not only in sewers, but in the treatment of sewage has never been greater – especially in the most densely populated areas. However, the Western approach of taking all waste to a central treatment plant is expensive and so may not be the best solution.

Onsite treatment technologies such as off-grid toilets or decentralised treatment plants are rapidly developing and may help improve river water quality sooner, enabling more and more people to celebrate Kumbh Mela safely.

Doyle Rice, USA Today January 15, 2019

Any hopes we had for a mild end to January appear to be over.

Just as the western storm onslaught is ending, a pair of winter storms will dump snow and ice across the central and eastern U.S. over the next several days, with the second storm a potential blockbuster in some spots, with a foot of snow possible.

Then, courtesy of our old friend the Polar Vortex, an icy blast of bitterly cold air straight from the Arctic will freeze most of the eastern U.S. next week. Unfortunately for warm weather fans, it’s only a preview of what forecasters are calling a brutal, punishing stretch of intense cold that should last well into February.

As for this week’s storms, while the first one will be more of a nuisance, the second one will be a “major snowstorm,” according to AccuWeather meteorologist Bernie Rayno.

The first one will sweep through the Midwest and into the Northeast starting late Wednesday and ending early Friday. Cities such as Detroit, Buffalo, Albany and Boston can expect light snow (1-3 inches) and slippery travel from this storm, AccuWeather said. A few school delays and closures are possible.

The second, more powerful storm will bring heavy snow from the upper Midwest to the Great Lakes to northern New England. Cities such as Cleveland, Buffalo, Syracuse, and Burlington, Vermont, may see a foot or more of snow. The snow should miss the big cities of the I-95 corridor from Boston to Washington, D.C.

Then, the cold: A blast of arctic air, the coldest of the season, is headed into the central and eastern U.S. late this week into the weekend, part of a colder pattern change right on cue with what is typically the coldest time of the year, Weather Channel meteorologist Chris Dolce said.

The temperature in Kansas City at the kickoff of the AFC Championship Game Sunday night will be about 6 degrees, with a wind chill of about 3 below zero, the National Weather Service predicts.

The cold is partly due to the fracturing of the polar vortex earlier this month, which has slowly pushed unspeakably frigid air from the Arctic into the U.S.

By Monday morning, much of the upper Midwest will see below-zero temperatures, while temperatures will dip below freezing all the way to the Gulf Coast. These readings are some 15-20 degrees below normal in the Southeast, and about 20 to 30 degrees below normal in the Great Lakes and Northeast, according to weather.us meteorologist Ryan Maue.

And the snow and cold has only gotten started: “This is a going to be a wild, wintry ride for the eastern U.S. during the end of January,” said Michael Ventrice. a meteorological scientist at the IBM-owned Weather Company.

More chilling: Once this wintry pattern becomes entrenched, it may be difficult to dislodge, Judah Cohen, a researcher at Atmospheric and Environmental Research, told the Capital Weather Gang.

“These impacts can last four to six, and maybe eight, weeks,” said Cohen.

January 12, 2019

Father: What are you feeding them

Daughter: Pollen

#beelove in Kuwait

Father: What are you feeding themDaughter: Pollen#beelove in Kuwait

Posted by Natural Beekeeping Trust on Saturday, January 12, 2019

Addressing the water crisis head on, multiple healthy food initiatives are working to improve health, nutrition, and food security while jump-starting the local economy.

By Brian Allnutt, Health, Local Eats, Nutrition January 16, 2019

It’s a cold, snowy Thursday in Flint, Michigan, but business is more than steady in the Flint Farmers’ Market where Clinton Peck runs Bushels and Peck’s Produce. Locally grown micro-greens, beets, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage cover the booth, along with tropical fruit and other items he picked up at the produce terminal in Detroit. Elsewhere, the late lunch crowd is enjoying the offerings at the nearby restaurants. Later in the day, a group of kids from the city will participate in a cooking class in one of the market’s industrial kitchens.

It’s probably safe to say that this sort of diverse, foodie environment isn’t the picture most people conjure when they think of Flint—a town that is now synonymous with industrial decline and one of the worst public health crises in the nation’s recent history. Yet this market is booming—more than half a million people visited its 45 year-round and 30 seasonal vendors last year, according to farmers’ market managers.

What’s going on behind the scenes here is just as interesting. Peck’s produce stand operation is supported in part by a primary care pediatric facility called the Hurley Children’s Clinic (HCC), located in the same building. Through an initiative called the Nutrition Prescription Program, sponsored by the Rite-Aid Foundation, caretakers of children visiting the clinic receive a $15 voucher for fresh fruits and vegetables to spend at the market. Peck says he gets about $200 to $250 worth of business from these vouchers every market day.

The prescription program parallels other investments in the Flint food system designed to mitigate some of the worst effects of the water crisis. Programs like Flint Kids Cook—also coordinated by the HCC—as well as Double Up Food Bucks, Flint Fresh, and investments in community businesses such as the North Flint Food Market are helping Flint residents access fresh fruit and produce, as well as milk products, that are a proven to lessen the effects of lead on the body. For the most part, the produce that Peck sells and Flint Fresh distributes comes from outside the city proper, but Flint Fresh has a specific program of soil-testing and post-harvest handling for growers within the city limit to address lead concerns.

Double Up Food Bucks has grown since 2016, when it was used by 9 percent of SNAP households, to its present reach of over 50 percent. Other promising signs of growth include the facts that Flint Fresh is developing a regional food hub for food processing that could help area growers, and the North Flint Food Market just received a large grant from the Michigan Good Food Fund. In addition to getting healthy foods into the hands of more people, these initiatives are creating openings for the development of sustainable local businesses—and laying the foundation for radical change by giving citizens more control over their health and livelihood.

“Flint is a city like Detroit that is essentially having to re-imagine itself and rebuild itself from the ground up,” says Lisa Pasbjerg, market manager for the nonprofit Flint Fresh. “We want to get fresh produce to our community, but of course we also need to build and have a sustainable local economy.”

Balancing these two efforts hasn’t been easy. Although many nonprofit initiatives have expanded in the city and benefitted small businesses, 42 percent of Flint’s population lives in poverty, according the U.S. Census Bureau, and much of the development is clustered around a gentrifying downtown.

Increasing Access to Nutrition—With a Focus on Children

In 2014, the Flint Farmers’ Market moved to a new location next to the Mass Transportation Authority Transit Center—the source of 80 percent of Clinton Peck’s customers—and also near the YMCA and other amenities. The move preceded the water crisis, as did the co-location of the Hurley’s Children Clinic, but these changes took on a prophetic quality as the fallout from the disaster hit the city.

Since the water crisis, various programs have effectively helped residents—especially young ones—access the fresh food for sale in the market.

When the Nutrition Prescription Program launched in 2016, it gave patients small bags of fresh produce or $5 produce vouchers. As it continued, Amy Saxe-Custack, an assistant professor at Michigan State’s Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, who runs it along with other researchers, realized their clients weren’t just using these benefits to supplement their diets, but to meet basic food needs. With additional funding from the Rite-Aid Foundation, the HCC was able to increase the amount of the vouchers from $5 to $10 dollars later in 2016 and then from $10 to $15 in 2018.

This effort is groundbreaking for its focus on children and preventative medicine. Saxe-Custack says that most of the food prescription initiatives in other parts of the nation focus on low-income adults with chronic conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes.

“From a dietary perspective, there is tons of evidence to suggest that dietary patterns are established early,” she says, and the attendant research she’s doing for the program may provide some data that could establish it as a model.

A cooking class at Flint Kids Cook. (Photo courtesy of Michigan State)

A cooking class at Flint Kids Cook. (Photo courtesy of Michigan State)

Families using the center also expressed a desire to teach their children how to cook. This inspired Flint Kids Cook, which launched in 2017, sponsored by an anonymous family foundation in New York City that wanted to do something about the water crisis, says Saxe-Custack. Initially the program had trouble attracting enough young people to participate. But now the class at the market has a waiting list and is expanding to other sites in the city.

Saxe-Custack believes the success of the classes stems from the fact that it’s not just a nutrition class or cooking demo: “They’re measuring, they’re mixing, they’re cutting, they’re over a stove … It’s actually hands-on cooking,” she says.

And chefs from the market, such as Ian Diem of Chubby Duck Sushi, help teach the class. “The kids are enamored with the chefs,” as Saxe-Custack puts it. The class could also prepare kids for jobs in a sector that appears to be growing in the city.

Food System Investments Putting Power in Residents’ Hands

The economic benefits of charitable investments in the food sector have grown thanks to programs like Double Up Food Bucks as well. Administered by the Fair Food Network, a national nonprofit that has been using federal, state, and philanthropic funding to match SNAP benefits spent on fruits and vegetables for a decade. At the Flint Farmers’ Market, the effort has translated into more than $110,000 of additional sales annually, according to market manager Karianne Martus.

After the water crisis, the Fair Food Network set out to grow the program by stepping up their outreach to the people of Flint, where they had already established a strong base for the program. They also allowed people to use Double Up Food Bucks on dairy products because calcium has been shown to decrease the absorption of lead in the body.

Since October 2016, the number of residents using the Double Up program has grown from 4,000 to over 13,000. And Holly Parker, senior director of programs at the Fair Food Network, estimates that over 50 percent of SNAP recipients in the city are using the program, which brings more business to people like Peck at the farmers’ market, who says it has boosted his sales by between 8 and 12 percent.

Clinton Peck of Bushels and Pecks at the Flint Farmers’ Market. (Photo courtesy of the Flint Farmers’ Market)

Clinton Peck of Bushels and Pecks at the Flint Farmers’ Market. (Photo courtesy of the Flint Farmers’ Market)

Flint Fresh was also created to respond to the water crisis and is aimed at improving nutrition and food security while supporting local business. Along with mobile farmers’ markets, they deliver around 300 boxes of fresh produce to local families and individuals every month. Both platforms accept Double Up Food Bucks and Nutrition Prescription vouchers, as well as prescriptions from other programs. In the summer, 50 percent of the produce comes from local farms, some of them in Flint itself.

Flint Fresh’s Pasbjerg says that her organization is in the initial phases of building a regional food hub that would help the organization distribute produce. “The idea is that, long term, we would be able to process stuff for local farmers,” she says, “and then use that in the school systems and for local grocery stores.”

In addition to Double Up Food Bucks, the Fair Food Network is partnering with Capital Impact Partners, MSU’s Center for Regional Food Systems, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to invest in Flint as part of the Michigan Good Food Fund, which provides financing and counseling to organizations promoting healthy food access, economic development, and other goals. Among this year’s award winners is the North Flint Reinvestment Corporation, which will be receiving $40,000 to help create the city’s first member-owned co-operative grocery store, the North Flint Food Market.

The co-op is another example of the way the water crisis—as well as the disappearance of two large grocery store chains—engendered the desire for radical change. “The conventional food system isn’t going to come back into that neighborhood,” says Rick Sadler, assistant professor of Family Medicine at Michigan State and a member of the store’s steering committee. Starting the co-op was, in Sadler’s words, a way of “putting the power of the investment in the hands of the residents.”

The Challenges of Radical, Food-based Change

Despite all these positive changes, however, the city still faces structural problems caused by overall disinvestment in most of its neighborhoods and the clustering of new investment around Flint’s small downtown.

For these reasons, Flint businesses will still face a lack of a customer base for the immediate future, Sadler says. “It’s just so hollowed-out, and the momentum of getting investment back into the city has been so slow-going,” he added.

There’s also the fact that most grant-based initiatives don’t offer permanent funding. Double Up Food Bucks, according to Emilie Engelhard, senior director of external affairs for the Fair Food Network, seems to be secure after the Senate voted to protect healthy produce incentives in the most recent farm bill. And the Nutrition Prescription Program is funded through 2019 at the farmers’ market and through May 2020 at a second location. But relying on grants for economic stimulus will always be an uncertain proposition.

The exact potential of food businesses as an economic driver in Flint is also unknown. One study based in Detroit, which is 60-some miles away from Flint and dealing with similar structural issues, found that food was the third-largest employment sector in the city and could soon move to second.

Similar research hasn’t been done in Flint, but the city’s master plan projects that “food and hospitality” jobs in the county will be increasing 51.9 percent by 2040, second only to “health care and social assistance.”

Given this projection—and the progress these initiatives have made so far—Flint’s ability to use some of its current nutritional programming to bring investment back to the city could then be a very important for Flint residents. Although Pasbjerg emphasizes that in one of the nation’s poorest cities, “there’s a ton that needs to be done still.”