SLEEPING BEAR DUNES NATIONAL LAKESHORE — The divers leaned back from the edge of the boat and splashed into water, bobbing up for a moment before dropping down to a world just a few miles off the northern Michigan coast — and worlds away from the one above the surface.

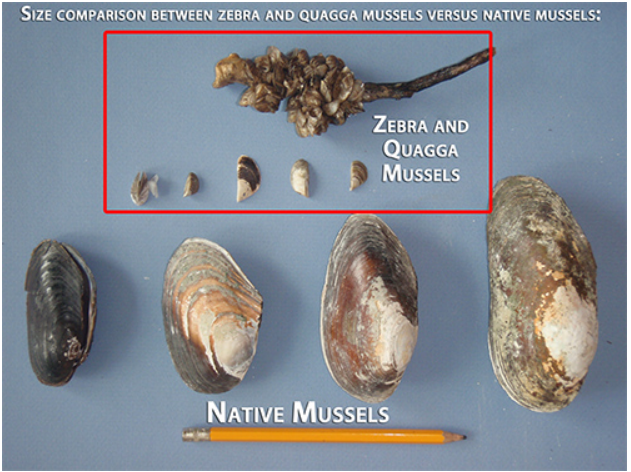

Today in Lake Michigan, quagga mussels, Eastern European invaders generally smaller than a stamp, reign over an upended underwater ecosystem. The mussels arrived in the Great Lakes more than three decades ago, eating, excreting and spreading zealously ever since, attaching themselves to everything from water intakes to shipwrecks, and all the while filtering life out of the food chain and a $7 billion fishing industry.

But solutions in open water, at least on a small scale, are starting to seem possible to soften the bivalves’ brunt.

Experiments are playing out in Lake Michigan with hopes of restoring fish spawning habitat. Manually removing mussels, with another invasive species offering an assist, has kept rocks clear. Other treatments from copper compounds to genetic biocontrol are in the mix as a collaborative dedicated to mussel control plans for the future.

The Lake Michigan survey on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s 180-foot Lake Guardian research vessel, generally conducted every five years, just wrapped up. The bottom-dwelling census is essential to understanding what mussels have done to the lake in the last 30 years, and what they may do next.

Large-scale eradication is still a daunting idea with how many invasive mussels blanket Lake Michigan. By comparison, during peak migration, 30 million birds might fly over Illinois in a night. About 3 trillion trees cover the entire earth. The human body? Somewhere in the tens of trillions of cells.

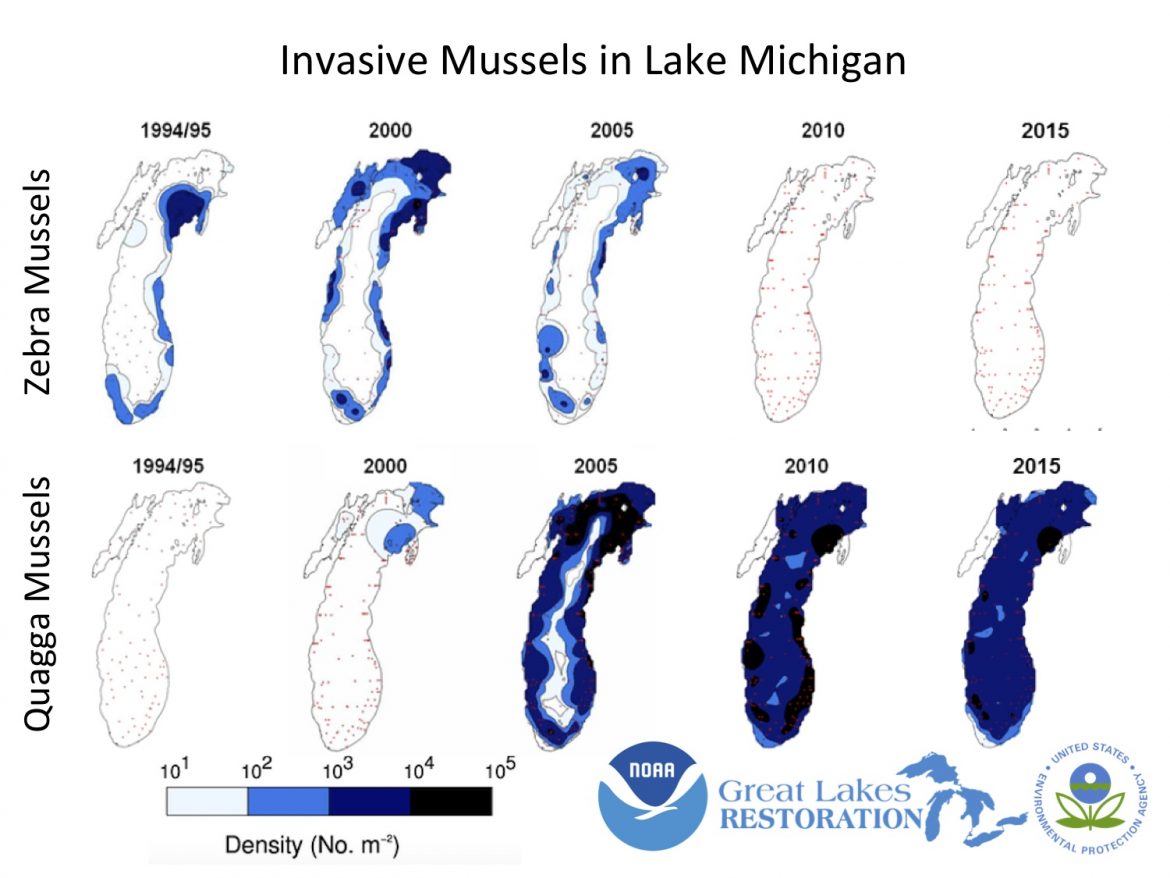

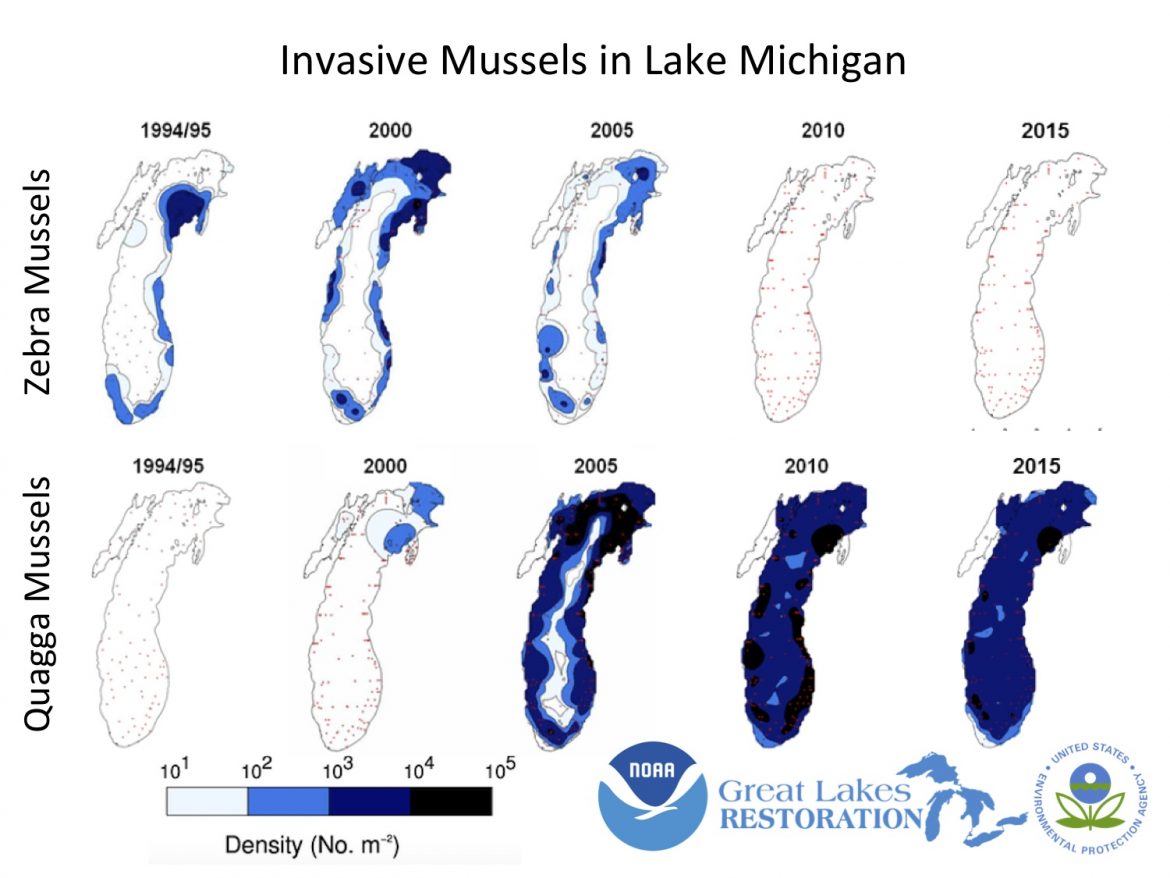

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientists estimate about 300 trillion mussels in the lake from the 2015 count — and the mollusks are growing at deeper sites, and growing larger.

More than a decade ago, between regular dives off the Wisconsin shore, Harvey Bootsma, a professor at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, told the Chicago Tribune the lake was “changing faster than we can study it.”

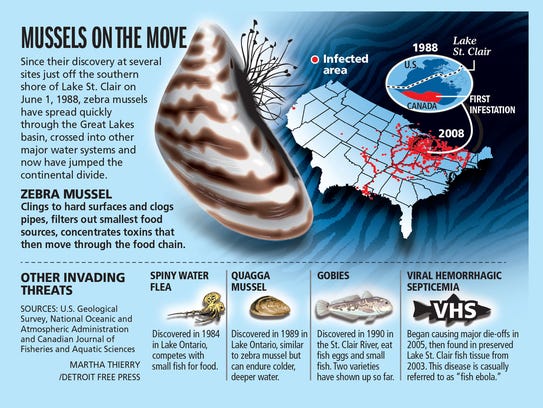

There are now more than 185 nonnative species in the Great Lakes region; some sneaked in through ships and human-made connections, while others, such as coho and king salmon, were introduced by people. Some acclimated with negligible — or even beneficial — consequences. The invasive mussels are among the most notorious of the unexpected visitors.

On top of the ecological damage caused to native mussels, fish and even shorebirds, they’ve cost billions — from clogging water intakes and power infrastructure, to damaging boats and docks.

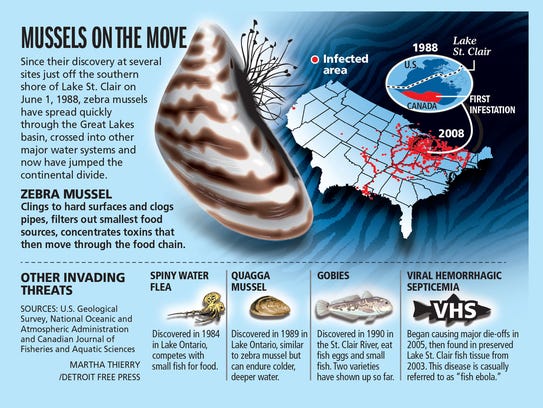

Zebra mussels came first; the Caspian Sea travelers discharged in the 1980s, likely via ship-stabilizing ballast water. Quagga mussels, filter feeders armed with a more impressive propagation arsenal, arrived soon after.

Unlike zebra mussels, which generally attach to hard surfaces and stick to shallower water, quaggas tolerate colder temperatures, softer sediment and outcompete zebras with less food available, meaning they now dominate Lake Michigan — and most of the Great Lakes. Only Lake Superior has been largely spared due to the lake’s chillier conditions and lack of calcium, which mussels need to strengthen their shells.

Years later, Bootsma is still studying how the mussels have transformed Lake Michigan, suiting up and diving down to an underwater laboratory.

“What we’ve learned in the Great Lakes is that prevention is a lot cheaper than trying to implement cures,” Bootsma said. “So it’s really important for us now to understand how we can prevent such dramatic changes happening in the future.”

As zebra and quagga mussels engulfed Lake Michigan, their colonies transforming rocks into shelled clumps and the lake bed into serrated carpet, they gobbled up phytoplankton at the base of the food web.

In the last 30 years, the bottom-dwelling czars have changed the look and chemistry of the lake: the water’s clearer, algae heartier, plankton scarcer. The nutrients — in the mussels’ control.

But, despite the improbability, if not impossibility, of large-scale mussel removal in Lake Michigan, Bootsma said it’s valid to ask: “Could we do it at scales large enough that there could be some positive impacts?”

Today, it’s still a challenge to get people to understand the widespread implications of the mussels, Bootsma said, because “most people don’t see what’s under the surface.”

Zebra mussels on a Lake Michigan Beach

Zebra mussels on a Lake Michigan Beach

If you went to Yellowstone National Park and discovered the bison were gone, you might be upset, he said. “The changes that have happened in the Great Lakes are more dramatic than that.”

Underwater landscape

On recent sunny days near Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, a boy in a red jersey cast a fishing line from an old wooden dock; a woman on the beach, legs crossed, read a newspaper under a blue-green striped umbrella; from the top of a bluff, Lake Michigan’s surface flickered like the last moments of a firework. All along the shore you could spot the broken halves of bleached mussel shells.

A few miles out on the lake, framed by the towering dunes, U.S. Geological Survey scientists dove down to get a good look at Good Harbor Reef, a mix of cobblestones and sandy stretches.

They’d usually be diving to collect samples, said research fisheries biologist Peter Esselman, but as part of a project with the National Park Service, they were collecting 360-degree video footage to help people understand the underwater landscape — and its challenges. At Sleeping Bear, that includes invasive species.

On one dive, Glen Black, a biological science technician, scooped up mussels and crunched them in his hand for the video.

Along the lake bottom was another invasive species, Black said, the round goby — an invasive fish also from Eastern seas, now plentiful in Lake Michigan.

“You just see the bottom moving everywhere,” he said.

Esselman came up from a dive and stretched his hands beyond half a foot: “The algae’s about this high.”

As the mussels occupied the reef, so did nuisance cladophora algae, which appears to be linked to botulism outbreaks that left piles of birds — including endangered Great Lakes piping plovers — dead in the sand.

The mussels also choked historically important spawning grounds, just a few miles from Leland Harbor and Fishtown, where you can line up for fresh lake trout and whitefish.

The reef has subhabitats of sorts, some more optimal for fish spawning and mussel attachment than others, said Ben Turschak, a fisheries research biologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. The department is working with the park service and geological survey to map and identify fish spawning habitat.

“That’ll help prioritize any kind of restoration or protection that we would do in the future,” Turschak said.

The places where native fish spawn aren’t infinite, said Brenda Moraska Lafrancois, aquatic ecologist with the National Park Service. “So we don’t need an infinite amount of invasive mussel removal effort either.”

“I think we’re actually getting to a point where you can envision a future where the most important parts of Good Harbor Reef are restored to some semblance of natural habitat,” she said.

Round goby’s role

The story of mussel removal in Lake Michigan is also the story of the reef, where researchers have tested hypotheses related to algae, mussels and bottom-dwellers for more than a decade. In 2016, they scraped off nearly 1 million mussels from an area the size of a studio apartment.

Scientists thought the mussels, whose millions of young float in the water and then settle down to colonize, might re-blanket the rocks after a year or two.

Five years later, some mussels occupy crevices, but the rocks are still largely mussel free.

Scientists think the round goby helped.

“They like small mussels because their shells are easier to crush and they’re easier to digest,” Bootsma said. “So we think what’s happening is that those rocks that we scraped just can’t get recolonized because anytime some small mussels settle on them and try to start growing, the gobies pick them off right away.”

Scientists are studying how the goby might give back to the food web; the fish are credited with reviving the Lake Erie water snake population. But they devour other small invertebrates — and native fish eggs.

Bootsma’s team set up a cage this summer with mussel-free rocks that are inaccessible to the gobies to see whether the mussels can recolonize.

“If the round gobies had gotten to the Great Lakes first, we might have avoided a lot of problems with invasive mussels,” Lafrancois said. But “invasive mussels are also probably part of why round gobies had such an easy time establishing here.”

The mussels also fed a “perfect storm for algae,” Bootsma said.

Nuisance cladophora algae was prevalent before controls aimed at reducing phosphorus from sewage pollution, farm runoff and detergents in the 1970s were put into place. The decaying shaglike mats announce their presence via a stench of rotting eggs.

Capable of filtering the entirety of Lake Michigan in less than two weeks, the mussels allowed more sunlight to reach the lake bottom where the algae grows — Lake Michigan is now sometimes clearer than Lake Superior — and their excreted nutrients offered an extra boost to algae growth.

In the removal patch, phosphorus content is lower in the algae on previously cleared rocks, in line with scientists’ hypotheses. But algae has returned to the rocks — another piece of the puzzle that keeps sending them underwater.

Ripple effects

In 2014, the EPA approved open water use of the molluscicide Zequanox, a treatment made up of dead cells from a soil bacteria that specifically targets mussels by destroying their digestive systems. A year later, the Invasive Mussel Collaborative formed.

“People thought, well, maybe there is something we can do about this,” said Erika Jensen, executive director of the Great Lakes Commission. “And we don’t just need to throw up our hands and accept that they’re here.”

As the collective, including the Great Lakes Commission, Geological Survey, NOAA and the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, among others, began to think about potential sites for mussel control projects, Good Harbor Reef, already a testing ground, was a natural fit.

But there were questions about how and where Zequanox could be used, and what would happen to a post-mussel ecosystem if they suddenly disappeared.

“If we were to be able to control them or suppress their populations to a significant degree, what ripple effects does that have for the rest of the ecosystem?” Jensen said. “And we still don’t have all the answers to that.”

A frame and tarp system was designed to pump Zequanox to cordoned-off areas of Good Harbor Reef over a few days in August 2019.

Bad weather caused delays — a challenge of working in open water — but mussel density was soon reduced by 95%.

Since, populations have crept back up more than the manual removal site; scientists think the treatment missed some mussels underneath rocks. But they’re still not as abundant as surrounding areas.

This summer, Bootsma hopes to try another control method at Good Harbor involving tarps — cheaper and less logistically demanding, but one that may take a lot longer to work.

The mussels would essentially be starved and smothered.

Aside from removal efforts, the findings from Good Harbor can help contribute to the development of mathematical models to play out future scenarios.

“You can say to the model, OK, now let’s see what happens to Lake Michigan if we reduce the number of mussels to 50% of what they are now, or if we warm the lake up by 3 degrees as a result of climate change,” Bootsma said. “And that’s really useful for managers because we want to know, for example, is there going to be more or less plankton in the future to support the food web and important fish in the lake?”

Growing larger

Lowell Friedman looked out on calm water and a smoky sky at Leland Harbor. He and his wife, a Michigan native, came to buy fresh fish on vacation. And, as kayakers, they’re familiar with invasive mussels.

“In the last 10 years we’ve now seen it move from just boaters to everything that enters the water has to be checked for mussels,” Friedman said.

The checks aren’t much of an inconvenience, and they’re necessary, he said, listing off the damage mussels have caused. And, Friedman said, “It keeps the ecosystem out of balance.”

A group within the mussel collaborative is developing a list of high-priority locations where control may be beneficial, looking at factors including: fish spawning and nursery habitat, cladophora algae and native mussel distribution, water intake infrastructure, and threatened and endangered fish species.

“They’re not good for fisheries, that’s for sure,” said Bob Lambe, executive secretary of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

Some Great Lakes fish have struggled through overfishing, pollution, the arrival of alewives and the devastation wrought by the invasive blood-sucking sea lamprey. Species like lake trout and salmon are somewhat stable in Lake Michigan, Lambe said, but mostly through aggressive restocking rather than natural reproduction.

In the latest survey of Lake Michigan prey fish, food for salmon and trout, their collective weight is comparable to surveys since the mid-2000s. But it’s still a fraction compared with earlier decades.

The mussels are faring better.

In 2015, 300 trillion mussels were counted in Lake Michigan, a drop from 480 trillion a decade ago, said Ashley Elgin, a research scientist with NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. But they’re growing larger and heavier, increasing from about 40 million tons to 50 million tons, collectively weighing more than 300,000 hefty blue whales.

The overall mussel population may be stabilizing, but in deeper offshore reaches, which comprise more than half of the lake, populations have grown slowly and steadily.

“Monitoring’s important so that we have our finger on the pulse with what’s happening with the population,” Elgin said. “Mussels are one of the major drivers and major stressors in the lake, so to understand where their populations are at helps us understand how the rest of the food web is responding.”

Monitoring food-web changes

During the Lake Michigan survey on the Lake Guardian, scientists send down devices called Ponar grabs, which scoop up the lake bottom for sampling.

Throughout Ponarpalooza — the affectionate term given to the survey — there’s excitement, and trepidation, in seeing food-web changes firsthand. The bottom-dwellers are good indicators of ecosystem health and change, said EPA environmental scientist Beth Hinchey Malloy.

“Everybody gathers around on the back deck when they’re bringing up those Ponars from the deep sites, because the big question is, are we going to find diporeia or not?” Malloy said. “And when you find them, a big cheer erupts on that back deck.”

Before mussels, diporeia, a shrimplike fish food, were the predominant bottom-dwellers, and an energy-rich food source. The “Snickers bars of the deep,” Elgin said. But they keep disappearing.

Scientists on the Lake Guardian also used video technology, a newer tool to assess mussel coverage. A map from SUNY Buffalo State scientists is expected soon.

“There’s a lot of anticipation to see what these population curves are going to look like with this new data from 2021,” Malloy said.

How climate change may affect mussel populations — as even the depths of Lake Michigan are warming — is another question. Warming water may help mussel growth, Elgin said, but may also hamper food availability.

For now, with populations in the hundreds of trillions, the mussels are a driving force.

“The quagga and zebra mussels, they’re true ecosystem engineers,” Elgin said.

Advocates and officials are still fighting for more stringent ballast water regulations to prevent the next invader from occupying waterways.

Scientists, meanwhile, fixate on the ones already here, building on each small victory.

Zebra mussels on a Lake Michigan Beach

Zebra mussels on a Lake Michigan Beach