CNN

Are the annual climate summits working? These countries are going to the courts, instead

Ella Nilsen, CNN – November 29, 2023

Few leaders paint a picture of the climate crisis as vividly as United Nations chief António Guterres. He has accused world leaders of opening “the gates of hell” and said the planet is “heading into uncharted territories of destruction” after deadly heat waves and floods.

“The current fossil fuel free-for-all must end now,” Guterres said last year. “It is a recipe for permanent climate chaos and suffering.”

Yet the UN climate summit, known as COP, is tedious. It is full of jargon, snail-paced developments and painful consensus-building that can be broken by a single country’s veto.

Now some are asking: Is the process even working? Some small island nations — countries that are facing irrevocable change from rising seas — say no.

Over the decades, these painstaking negotiations have worked to prevent several catastrophic degrees of global warming. COP’s biggest win was the Paris Agreement, widely seen as one of the most effective environment treaties, which set a goal to limit global warming to well under 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1.5 — a target that climate scientists, advocates and most countries have since rallied around.

Before those talks, the world was on track for roughly 4 degrees of warming. Countries’ pledges after Paris pushed that to 2.5 to 2.9 degrees, according to recent UN figures.

But the Paris Agreement was voluntary by design, in large part due to the influence of the US, and it relies on a system of collective shaming and competitive ambition in lieu of legal consequences. It contained “very few obligations” for major polluters, said Payam Akhavan, an attorney for the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law.

Vanuatu, Tuvalu and Antigua and Barbuda are now asking international courts to issue “advisory opinions” that could fundamentally change future COPs by compelling countries to set legally binding targets to cut climate pollution, rather than voluntary ones.

“The turn toward international litigation is an attempt to put some teeth in the toothless Paris regime, by declaring the 1.5-degree target is a binding target and not discretionary,” Akhavan told CNN.

As world leaders head to Dubai for COP28 this week, this courtroom strategy is raising eyebrows among the United States’ current and former climate negotiators, who say that while diplomacy can be stubborn and slow, it yields progress.

Even fierce climate advocates who agree COP should be more ambitious still believe the summit is a powerful and worthwhile endeavor.

“There is a lot of questioning whether this process will deliver or not,” Ani Dasgupta, president and CEO of international climate nonprofit World Resources Institute, told CNN. “However, I believe COP, or some version of COP, will remain and absolutely is needed. This is the only forum that I know where poor countries actually have a place at the table that is equal, to negotiate with rich countries across a vastly important topic.”

‘Countries move farther when they move together’

COP’s detractors and advocates alike agree it is a crucial annual meeting, but also one that is plodding and technical. An errant word or piece of punctuation can derail negotiations, and it can — and often does — take years for incremental progress to happen.

“I would say it’s necessary, but maybe not sufficient,” said Sue Biniaz, the deputy for US climate envoy and former Secretary of State John Kerry.

Biniaz has a lot of experience at COPs; she was the United States’ lead climate lawyer for more than two decades and was one of the key authors of the Paris Agreement.

Both Biniaz and other former top US climate negotiators told CNN that although each climate summit is often judged as a singular event, it is more important to look at the year leading up to it.

“It’s necessary because the fact that it meets annually and puts pressure on countries is a good thing, and we’re in a lot better position with the annual COPs and the Paris Agreement than we would have been without it,” Biniaz told CNN. “At the same time, it is really difficult and challenging to get agreement among everyone in the world, particularly when you have geopolitical issues, and some countries may be more motivated to reach agreement than others.”

International politics and the dynamics within countries matter to the success or failure of COP. There is no better recent example of than the shockwave that surged through the summit when former President Donald Trump pulled the US out of the Paris agreement in 2017 — a move President Joe Biden reversed upon taking office.

Still, former and current US negotiators say climate diplomacy has helped keep the world’s temperature from reaching truly alarming highs.

“If you look at those first assessments coming out of the scientific community back then, we were looking at an incremental temperature gain of about 7 degrees,” said Jonathan Pershing, a former Kerry deputy who now directs the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s environment program. “Seven degrees, today, is unimaginable.”

Pershing added that the fact the world’s governments are now racing to keep to below 2 degrees of warming is an “extraordinary transition.”

“The collective endeavor has fundamentally altered the trajectory of greenhouse gas emissions,” Pershing said. “I think countries move farther when they move together.”

The annual summit has also become the most visible rallying point for global climate action, former US climate envoy Todd Stern told CNN. The summits used to largely be a gathering of only government climate negotiators, but each year COP becomes much larger — drawing advocates, businesses (including fossil fuel companies) and think tanks from all corners of the globe.

Stern thinks the growing spectacle of COP is a positive force, impossible to ignore even for groups that used to deny climate change’s existence. Even US House Republicans have sent a delegation for the past two years.

“It’s a two-week moment in the course of the year when people around the world — or at least some meaningful subset of people around the world — are paying attention to it,” Stern said. “That needs to keep getting bigger and bigger and bigger because that puts pressure on governments.”

Too little, too slow

Attorneys for the small island nations who are rocking the boat at COP say the proof it isn’t working is in the extreme heat felt around the world this year, and the global records smashed.

The world’s governments are working to hold global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius — above which scientists say a hotter world with more severe droughts and intense storms will become difficult to adapt to.

But 1.5 degrees is no longer an abstract concept; the world briefly crossed that temperature threshold this summer, though scientists caution it will take several years above that limit to say with confidence it’s been officially exceeded. This summer was a taste of life at this threshold: Wildfires raged across Europe, mighty rivers like the Mississippi and the Amazon fell to new lows, and hot-tub-like ocean water killed coral reefs and rapidly intensified hurricanes and cyclones.

“It’s not as if 1.5 is safe in any way, but we are very much on track to cross it,” said Margaretha Wewerinke-Singh, an international lawyer representing the island nation Vanuatu in climate litigation at the International Court of Justice. “Clearly we need more mitigation ambition to make sure we don’t end up with an unlivable world.”

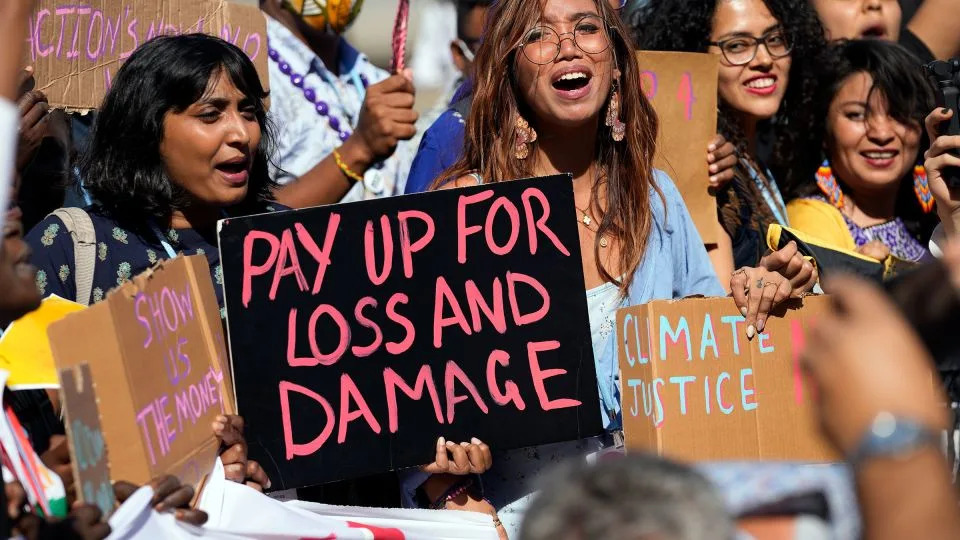

The potential for an unlivable world weighs heavily on young COP negotiators, who are urging swift action to cut climate pollution.

Hailey Campbell, a 25-year-old, Hawaii-based climate adaptation specialist who successfully lobbied for more official youth representation at COP, told CNN it is sometimes disconcerting to spend long hours and days at international summits debating the precise words on climate finance and ramping down fossil fuel use, then return to her Honolulu home and see climate impacts first-hand.

“You go back home and you’re like, ‘sea level rise is still here, [we] still need to do something about it,’” said Campbell, the co-executive director of advocacy group Care About Climate. “If I had to pick just one thing to come out of this year’s COP, it would be language to commit to an equitable phase-out of all fossil fuels.”

Two of the world’s highest courts are expected to weigh in on the small island nations’ cases as soon as next year. While the advisory opinions alone can’t force faster action from countries, it can “inject some urgency, some political will, some vision” into the annual climate talks and protect the “inalienable rights” — the very survival — of these disappearing nations, Wewerinke-Singh said.

“I think that the COP process has failed,” Akhavan said. “But we must make it work because we have no other choice.”