Yahoo News

Trump won’t save the air and water — but cities can

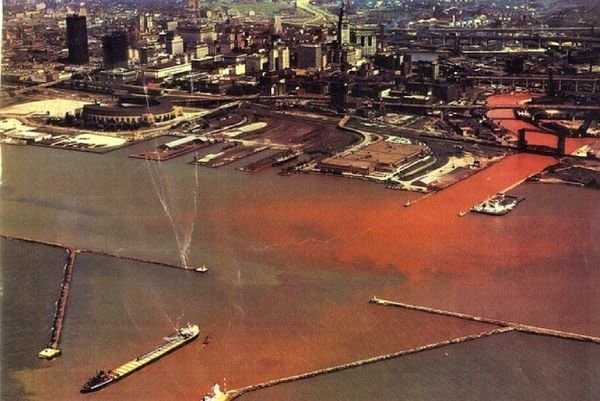

WASHINGTON — A wise man once said that you can’t step into the same river twice. Some rivers, you shouldn’t step into even a single time. That used to be true for the Cuyahoga, which snakes through downtown Cleveland before emptying into Lake Erie. For most of the 20th century, it was legal to dump waste into waterways. So the industries along the Cuyahoga dumped, and dumped — and dumped some more. The river’s surface crusted over with debris, and where the water was visible, it was black with oil.

Then, on June 22, 1969, a train crossing a bridge across the Cuyahoga near the Republic Steel mill caused sparking, which fell toward the oil-thick surface. It’s not hard to imagine what happened next. Time magazine published images of the river aflame (the pictures were actually from an earlier Cuyahoga fire). “Some river! Chocolate-brown, oily, bubbling with subsurface gases, it oozes rather than flows,” the article read.

Randy Newman even wrote a song about the Cuyahoga fire. “Burn on, big river, burn on,” Newman’s song went, “Burn on, big river, burn on.” You’ll never guess the title of his ballad to the Cuyahoga: “Burn On.”

But 50 years later, the Cuyahoga is a point of pride for Cleveland, having been the focus of a $3.5 billion restoration effort that has helped anchor a broader revitalization of Cleveland. And it has just been named “River of the Year” by American River, a Washington-based organization focused on protecting the nation’s waterways. The near-miraculous recovery of the Cuyahoga is a testament to the efforts of local officials, begun by then Mayor Carl Stokes — and to the success of one of the most significant pieces of environmental legislation in the nation’s history, the Clean Water Act, which the Trump administration is now attempting to undercut.

“It’s a dramatic comeback for the Cuyahoga,” says Chris Williams, vice president for conservation at American River. For Clevelanders, the comeback is also an affirmation of the Midwestern spirit.

“We were never the ‘Mistake by the Lake,’” Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, told Yahoo News, referencing the nickname with which Cleveland was tagged after 1969.

“We like to call ourselves ‘Gritty City,’” adds Matt Gray, Cleveland’s chief of sustainability. Like Brown, he plainly dislikes the image of Cleveland as a post-industrial landscape for ruin-porn aficionados. Cleveland, for him, is a “green city on a blue lake,” a slogan that has become popular in this once-sooty town. Under the guise of Sustainable Cleveland 2019, Gray and other city officials have pushed a plethora of green initiatives, from cleaning up brownfields to encouraging farm-to-table dining.

This must all seem highly improbable to anyone who was there in 1969. Because by then Cuyahoga had burned plenty of times before, Clevelanders hardly noticed, with the city’s paper of record, the Plain Dealer, giving the story the dog-bites-man treatment. “Just another fire on a river that had ignited many times before,” as former Environmental Protection Agency engineer Michael Mikulka put it in a recent recollection of the incident. In fact, the river had been considered “an open sewer through the center of the city” as early as 1881.

It was Mayor Stokes, the first African-American to lead Cleveland, who realized that by publicizing the fire, he could bring attention to the Cuyahoga’s plight. The day after the fire, he went to the scene of the crime. Leaning against a wooden pillar on the river’s banks, with the bridge leading to Republic Steel behind him, Stokes treated the event like the newsworthy catastrophe it should have been — and would have been if such fires were not dismayingly commonplace. Stokes painted the city as a helpless victim of industry: “We have no jurisdiction over what’s dumped in there,” he complained.

The Time story appeared a few months after that. Far more importantly, in 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act — in part thanks to testimony Stokes and his brother, U.S. Rep. Louis Stokes provided — that made illegal the kind of dumping that had turned the Cuyahoga into a tinderbox of horrors. In the years that followed, Washington, Cleveland and Columbus, Ohio’s capital, were not always models of cooperation, but they did well enough to make sure that the Cuyahoga would never catch fire again. In 1998, it was declared an American Heritage River, one of 14 around the nation given such designation by the EPA. Today, its waters are inhabited by 60 species of fish. Bald eagles nest on its banks.

And Cleveland is a growing city, with luxury condominium buildings rising on the formerly blighted shores of the Cuyahoga. “You’re not gonna have stuff like the Flats on a river that’s full of oil,” explains Bob Wysenski, a retired Ohio EPA official, in an EPA video about the Cuyahoga. The reference is to the Flats East Bank, a massive redevelopment near where the Cuyahoga flows into Lake Eerie. The Flats represents the kind of upscale initiative that would have been unthinkable two decades ago.

Brown, who moved back to Cleveland from the suburbs five years ago, argues that conservatives for too long have been given license to peddle without much challenge what he says is the false narrative that “you either have good environment policy or good jobs policy.” Brown argues that “good environmental policy can be good jobs policy,” pointing to the massive solar-panel manufacturing plant now being built in Toledo, which is expected to add 500 jobs.

There are now 737,031 people across 12 Midwestern states working in renewable energy jobs, according to Clean Jobs Midwest, a nonprofit organization that studies the renewable energy sector of that region. Ohio, according to Clean Jobs Midwest, now employs 112,486 people in clean energy, which puts the state in eighth place nationwide for jobs in the renewables sector. By contrast, only 51,000 people around the country are employed in coal mining, an industry President Trump has promised to restore.

In the meantime, the Trump administration has moved to cancel or delay many of the environmental regulations that it believes hamper growth in the extractive industries and heavy manufacturing. Those are many of the same regulations that have kept river fires from becoming a normal occurrence of American life, on the order of say, early morning presidential tweetstorms.

Brown calls Trump a “tool of the oil and gas industry.” As harsh as that charge may be, Trump does have Andrew Wheeler, a former coal lobbyist, heading the EPA, and Department of Interior chief David Bernhardt, also a former lobbyist, carries a card with all of his potential conflicts of interests.

Wheeler’s predecessor at the EPA, Scott Pruitt, led a sustained assault on the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act before being forced to resign in ignominy last year. Pruitt cancelled the Waters of the United States rule, an Obama-era directive that had expanded the provisions of the Clean Water Act. According to Williams, the American Rivers vice president, that rollback could endanger 18 percent of the nation’s rivers and half of its wetlands. Pruitt also repealed Obama’s clean power plan, which would have hastened the transition away from fossil fuels. Bernhardt’s predecessor, Ryan Zinke — who like Pruitt ended his career as a public official in disgrace — wantonly leased public lands to oil and gas companies, endangering pristine areas across the West.

Wheeler, the current EPA chief, has spoken about returning the EPA to “its core mission,” but his favorite version of the EPA appears to be the one before there was any EPA to speak off. He has overseen — without any seeming concern — the attrition of hundreds of scientists from the agency and supports Trump’s proposed budget for his agency, which would see a 31 decrease in funding.

But as Williams of American River says, “the Trump administration can’t simply strip away protections by fiat.” It falls to cities and states to fight the administration in court. Attorneys general like Maura Healey of Massachusetts and New York’s Barbara Underwood, who has since left office, fought Pruitt in court, keeping him from critical victories in Trump’s war against the regulatory state. That battle will continue as long as Trump is in office: for the Cuyahoga, the Hudson and every other river in the nation.