Yahoo News

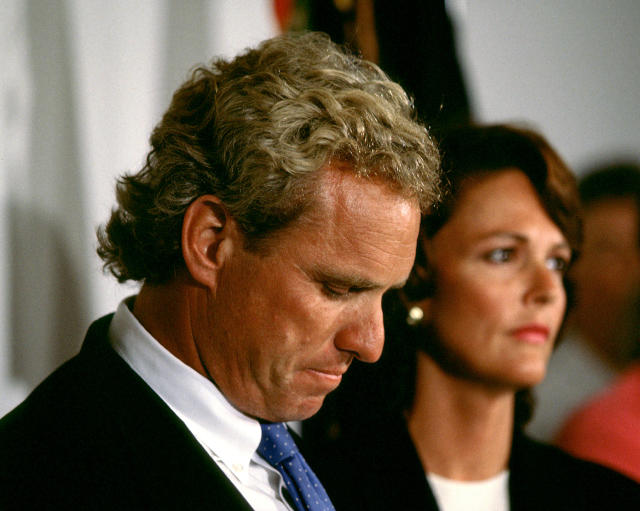

Joe Kennedy III carries the Kennedy legacy into the fight against Trump

Jon Ward January 30, 2018

When Republicans called Joe Kennedy III “rich” and “boring” the day before he was to deliver the Democratic response to President Trump’s first State of the Union address, they were really saying something else.

“There’s no there there,” they were saying. “He’s an empty suit. He is coasting on his family name and money.”

If you’re a Kennedy, it’s a familiar charge. Joe’s great-uncle Ted Kennedy, the former U.S. senator who died in 2009, was treated as “a joke” when he first ran for the Senate as a 30-year old assistant district attorney.

Sure enough, when Joe III first ran for Congress in 2012 — also on the basis of a résumé that mostly amounted to three years as an assistant DA — someone at a debate leveled the same epithet at him. “If your name were Joseph Patrick … and not Joseph Patrick Kennedy, based on your life experiences, would not your campaign be a joke?” a debate audience member asked.

As late as 1980, after 18 years in the Senate, Ted Kennedy had to confront the accusation that he was presuming to inherit the presidency from his late brother John, and his quest for the Democratic nomination fell short.

Joe III’s own father, Joe Kennedy II, abandoned a 1997 gubernatorial bid in Massachusetts because of a personal scandal, another recurring theme in Ted’s life and in the Kennedy family as a whole. But Joe II was also bedeviled by an over-reliance on his last name and the lack of a compelling vision for his candidacy.

That background, and the Kennedy penchant for bad behavior, may explain why Joe III was such a straight arrow in college — Stanford, not Harvard, although he went to Harvard Law School — abstaining from alcohol and gaining a reputation as a highly conscientious student. It sheds some light on why he spent two years with the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic.

On his office wall, there is a quote from his grandfather Robert F. Kennedy, the former attorney general who was assassinated in 1968 while running for president. “You can use your enormous privilege and opportunity to seek purely private pleasure and gain, but history will judge you,” the RFK quote reads.

Unlike his great-uncle Ted, Joe III seems to wear the weight of expectations well. He understands the power of the Kennedy name, springing from John F. Kennedy’s charismatic presidency and his martyrdom in 1963.

But he has been in no rush to become a political star. Kennedy, 37, has been a member of Congress for five years now and has remained relatively unknown beyond his district. He missed the December House vote on the Republican tax bill to be with his wife — whom he met at Harvard Law in Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s class — for the birth of the couple’s second child.

“I don’t think he gets out ahead of himself,” said Paul Watanabe, a professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts Boston. “He has been somebody who focuses on being what young congress-people do, which is focus on their district, focus on constituent services.”

Chosen by House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi to speak Tuesday night after Trump, Kennedy will now have much more visibility — and scrutiny. Already he has faced questions about his wealth, which was estimated at around $18 million in 2015. The Boston Globe reported in 2016 that Kennedy owned as much as half a million dollars’ worth of stock in a drug company called Gilead Sciences, which makes a hepatitis C drug that costs patients $1,000 a pill.

Even if many younger voters don’t know much about the Kennedy history, this new phase for Kennedy will bring more intense pressures on him.

“For people who may have loathed the Kennedys and saw them as representative of all that’s bad in the country — and there’s many of them — they may shift that to Joe,” Watanabe said. “On the other hand, many loved the Kennedys and thought everything they did was gold. On both sides it’s a little unfair and too much responsibility to bear.”

“The important thing is whether he comes out of this as his own person, and as a politician of the future and not of the past,” Watanabe said.

Kennedy family allies like Robert Shrum, a former adviser to Ted Kennedy, seem most anxious for Joe III to create some separation from the family heritage conveyed by his last name.

“I think he should be judged on his own, not as part of the family, or not as some kind of heir to Kennedy politics,” Shrum said.

Kennedy has gained some attention this past year. His remarks in a committee hearing challenging House Speaker Paul Ryan’s characterization of efforts to repeal Obamacare as an “act of mercy” went viral. A few other speeches have also drawn attention on social media.

But one of Kennedy’s more notable speeches came a year before he ran for Congress, when he addressed the Massachusetts legislature during a 2011 ceremony to commemorate the 50th anniversary of JFK’s inauguration.

Kennedy stood at the lectern with Ted’s widow, Vickie, seated on the dais behind him and began his remarks with a joke about JFK and former House Speaker Tip O’Neill, who also was a Massachusetts Democrat and a close Kennedy family ally.

Near the end of his 10-minute speech, Kennedy turned emotional as he spoke about the death of his grandfather, and connected it to the most recent violence in American politics. Rep. Gabby Giffords, an Arizona Democrat, had been shot in the head just a few days before.

Kennedy traced the roots of political violence back to extreme language, and he blamed both Republicans and Democrats for creating “an atmosphere of hate.”

“For too long the rhetoric in Washington has been toxic: antiwar protesters holding up signs saying ‘Death to terrorist pig Bush’; tea party protesters shouting out racist and antigay slurs to members of Congress; protesters shouting out ‘Death to Cheney’; radio talk show hosts calling President Obama and Democrats communists and traitors; images of both political parties showing opponents in the crosshairs of a rifle scope,” Kennedy said.

“This isn’t what President Kennedy stood for. It isn’t what [Martin Luther] King or Robert Kennedy stood for. They took on the big problems of our world. They looked to those common threads that unite us rather than diving into the identity politics to find those that divide us,” he said.

Kennedy’s willingness to call out both political parties could position him to speak to the whole nation Tuesday night. His speeches, Shrum said, include “the kind of thing that Democrats need to be saying if we’re going to reconnect with some of the people we lost in 2016, while keeping the people we had.”

And Kennedy’s condemnation of “identity politics” presaged a debate among Democrats now in the wake of Hillary Clinton’s loss to Trump. Liberals like Mark Lilla and others have blamed Clinton’s loss on a “fixation on diversity” that “has produced a generation of liberals and progressives narcissistically unaware of conditions outside their self-defined groups, and indifferent to the task of reaching out to Americans in every walk of life.”

Kennedy is certainly no cultural conservative. His guest at the State of the Union speech will be a transgender member of the U.S. Army, Staff Sgt. Patricia King. And he has been an outspoken advocate for gay rights.

But as he speaks to the entire country following Trump, whose first year as president has been defined by divisiveness, Kennedy may sound notes like the ones he closed with in 2011, which called on themes made into mantras by JFK and generations of Democrats after him.

“In times such as these, our commitment to each other and to our country cannot dip but is more critical than ever, drawing once again to something greater than ourselves, to lives of service and sacrifice, courage and judgment, integrity and dedication,” Kennedy said. “These are the ideals that ought to endure, rather than partisan rancor, naked self-interest, and other corrosive effects of promoting social divisions, a kind of moral gerrymandering that saps our spirit and degrades our collective will.”