🔥 Jake Tapper exposes HYPOCRISY of Pompeo, Graham and Giuliani on impeachment using their own words

Jake Tapper is a national treasure! 🔥🔥🔥Follow Occupy Democrats for more.

Posted by Occupy Democrats on Sunday, 13 October 2019

Category: Today’s News?

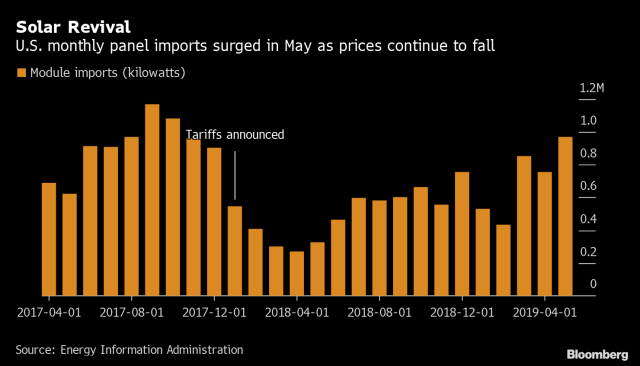

Trump Kills a Tariff Loophole in Latest Blow to Renewables

Bloomberg

Trump Kills a Tariff Loophole in Latest Blow to Renewables

(Bloomberg) — The Trump administration dealt a fresh blow to renewable energy developers on Friday by stripping away an exemption the industry was counting on to weather the president’s tariffs on imported panels.

The U.S. Trade Representative said Friday it was eliminating a loophole granted about four months ago for bifacial solar panels, which generate electricity on both sides. They’ll now be subject to the duties Trump announced on imported equipment in early 2018, currently at 25%. The change takes effect Oct. 28.

The exclusion had been a reprieve for the solar industry, which lost thousands of jobs and put projects on ice as a result of the tariffs. Some panel manufacturers had already begun shifting supply chains to produce more bifacial panels. Stripping the exemption is a blow to developers who build big U.S. solar projects. American panel makers First Solar Inc. and SunPower Corp. will regain an edge on foreign competitors.

“The solar tariffs are back,” Tara Narayanan, an analyst at BloombergNEF, said in an interview Friday. “U.S. solar developers cannot buy products with lower costs and higher output as they briefly thought they could.”

First Solar, the largest U.S. solar panel maker, rose 0.5% to $59.60 at 5:16 p.m. SunPower gained 0.7% to $10.62.

What BloombergNEF Says

“The withdraw of tariff exemption for bifacial will cool down its popularity in the U.S. a little, but not stop the rise of the technology, which introduces improved economics even without tariff exemption.”– Xiaoting Wang, solar analyst

Developers that have used bifacial panels and stand to take a hit from ending the exclusion include Renewable Energy Systems Americas Inc.and Swinerton Inc.

While bifacial panels accounted for just 3% of the solar market last year, BloombergNEF had projected a swift ramp-up in production as manufacturers tried to insulate themselves from U.S. tariffs.

The trade group Solar Energy Industries Association fought to preserve the exemption, saying bifacial technology held “great promise for creating jobs, right here in America.”

“We’re obviously disappointed,” the group’s general counsel, John Smirnow, said Friday. “We look forward to making sure the bifacial exemption gets a fair hearing” during the solar tariff’s mid-term review process.

The U.S. Trade Representative said in its filing that “the exclusion will likely result in significant increases in imports of bifacial solar panels, and that such panels likely will compete with domestically produced” products.

SunPower, based in San Jose, California, opposed the exemption without a cap, saying that it would otherwise defeat the purpose of the tariffs. “It just means everyone is going to make a bifacial,” the company’s chief executive officer, Tom Werner, said in a Sept. 23 interview.

–With assistance from Joe Ryan and Ari Natter.

To contact the reporters on this story: Brian Eckhouse in New York at beckhouse@bloomberg.net;Christopher Martin in New York at cmartin11@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Lynn Doan at ldoan6@bloomberg.net, Joe Ryan, Pratish Narayanan

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

CIA’s top lawyer made ‘criminal referral’ on whistleblower’s complaint about Trump conduct

Experts are raising questions about why the Justice Department did not open an investigation.

The lobby of the CIA Headquarters building in McLean, Virginia.Larry Downing / Reuters file

WASHINGTON — Weeks before the whistleblower’s complaint became public, the CIA’s top lawyer made what she considered to be a criminal referral to the Justice Department about the whistleblower’s allegations that President Donald Trump abused his office in pressuring the Ukrainian president, U.S. officials familiar with the matter tell NBC News.

The move by the CIA’s general counsel, Trump appointee Courtney Simmons Elwood, meant she and other senior officials had concluded a potential crime had been committed, raising more questions about why the Justice Department later declined to open an investigation.

The phone call that Elwood considered to be a criminal referral is in addition to the referral later received as a letter from the Inspector General for the Intelligence Community regarding the whistleblower complaint.

Justice Department officials said they were unclear whether Elwood was making a criminal referral and followed up with her later to seek clarification but she remained vague.

In the days since an anonymous whistleblower complaint was made public accusing him of wrongdoing, trump has lashed out at his accuser and other insiders who provided the accuser with information, suggesting they were improperly spying on what was a “perfect” call between him and the Ukrainian president.

But a timeline provided by U.S. officials familiar with the matter shows that multiple senior government officials appointed by Trump found the whistleblower’s complaints credible, troubling, and worthy of further inquiry starting soon after the president’s July phone call.

While that timeline and the CIA general counsel’s contact with the DOJ has been previously disclosed, it has not been reported that the CIA’s top lawyer intended her call to be a criminal referral about the president’s conduct, acting under rules set forth in a memo governing how intelligence agencies should report allegations of federal crimes.

The fact that she and other top Trump administration political appointees saw potential misconduct in the whistleblower’s early account of alleged presidential abuses puts a new spotlight on the Justice Department’s later decision to decline to open a criminal investigation — a decision that the Justice Department said publicly was based purely on an analysis of whether the president committed a campaign finance law violation.

“They didn’t do any of the sort of bread-and-butter type investigatory steps that would flush out what potential crimes may have been committed,” said Berit Berger, a former federal prosecutor who heads the Center for the Advancement of Public Integrity at Columbia Law School. “I don’t understand the rationale for that and it’s just so contrary to how normal prosecutors work. We have started investigations on far less.”

Elwood, the CIA’s general counsel, first learned about the matter because the complainant, a CIA officer, passed his concerns about the president on to her through a colleague. On Aug. 14, she participated in a conference call with the top national security lawyer at the White House and the chief of the Justice Department’s National Security Division.

On that call, Elwood and John Eisenberg, the top legal adviser to the White House National Security Council, told the top Justice Department national security lawyer, John Demers, that the allegations merited examination by the DOJ, officials said.

According to the officials, Elwood was acting under rules that a report must occur if there is a reasonable basis to the allegations, defined as “facts and circumstances…that would cause a person of reasonable caution to believe that a crime has been, is being, or will be committed.”

A DOJ official said Attorney General William Barr was made aware of the conversation with Elwood and Eisenberg, and their concerns about the president’s behavior, in the days that followed.

Justice Department officials now say they didn’t consider the phone conversation a formal criminal referral because it was not in written form. A separate criminal referral came later from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which was based solely on the whistleblower’s official written complaint.

When Elwood and Eisenberg spoke with DOJ, no one on the phone had seen the whistleblower’s formal complaint to the inspector general of the intelligence community, which had been submitted two days before the call and was still a secret. The issue of campaign finance law was not part of their deliberations, the officials said.

A ‘thing of value’

It is illegal for Americans to solicit foreign contributions to political campaigns. Justice Department officials said they decided there was no criminal case after determining that Trump didn’t violate campaign finance law by asking the Ukrainian president to investigate his political rival, because such a request did not meet the test for a “thing of value” under the law.

Justice Department officials have said they only investigated the president’s Ukraine call for violations of campaign finance law because it was the only statute mentioned in the whistleblower’s complaint. Former federal prosecutors contend that the conduct could have fit other criminal statutes, including those involving extortion, bribery, conflict of interest or fraud, that might apply to the president or those close to him.

The decision not to open an investigation meant there was no FBI examination of documents or interviews of witnesses to the phone call, participants in the White House decision to withhold military funding from Ukraine, the president’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, and Ukrainian officials who were the target of Trump and Giuliani’s entreaties.

Text messages turned over to Congress Thursday night, in which diplomats appear to suggest there was a linkage between aid and Ukraine’s willingness to investigate a case involving Joe Biden, were not examined as part of the Justice Department’s review, officials said, adding that they conducted purely a legal analysis.

Justice Department spokeswoman Kerri Kupec told NBC News that the decision not to open an investigation was made by the head of the criminal division, Brian Benczkowski, in consultation with career lawyers at the public integrity section. She and other officials declined to say whether anyone dissented.

The operative DOJ standard that the president can’t be indicted while in office was not a factor, she said. Attorney General William Barr has said he believes the president can be investigated and prosecutors can make a determination whether he committed criminal conduct.

“Relying on established procedures set forth in the Justice Manual, the Department’s Criminal Division reviewed the official record of the call and determined, based on the facts and applicable law, that there was no campaign finance violation and that no further action was warranted,” said Kupec.

Kupec declined to comment on whether the Justice Department was investigating any other aspect of the Ukraine matter. There has been no public indication, however, of any such investigation.

Some legal experts are puzzled by Justice Department’s narrow approach.

“They are not by any stretch of the imagination limited to the referral,” said Chuck Rosenberg, an NBC News contributor and former U.S. Attorney. “They have the authority — in fact, they have the obligation — to look more deeply and more broadly and bring whatever charges are appropriate.”

Berger added, “When you get a criminal referral, you don’t go into it saying, ‘This is the criminal violation and now I’m going to see if the facts prove it.’ You start with the facts and the evidence and then you see what potential crimes those facts support. It seems backwards to say, ‘We are going to look at this just as a campaign finance violation and oops, we don’t see it — case closed.'”

In a case in which a government official is allegedly using his office for personal gain, and pressuring someone to extract a favor, the bribery and extortion statutes are usually considered, Berger said. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits bribery of foreign officials, may also have been implicated, she said.

‘I have received information’

In his written complaint, the CIA officer who became the whistleblower framed his allegations this way: “I have received information from multiple U.S. government officials that the President of the United States is using the power of his office to solicit interference from a foreign country in the 2020 election.”

But when he first passed on his concerns, they were not so specific, officials said. He first complained at his own agency, sending word through a colleague to a CIA lawyer. The complaint eventually reached the spy agency’s top lawyer, Elwood, officials said.

She was told there were concerns about the president’s conduct on a call with a foreign leader, but not which leader, officials said.

She also was told that others at the National Security Council shared the concerns, so she called Eisenberg, the top NSC lawyer, officials said. He was already aware that people inside his agency believed something improper had occurred on the July 25 call with the Ukrainian president, officials said.

After consulting with others at their respective agencies and learning more details about the complaint, Elwood and Eisenberg alerted the DOJ’s Demers, during the Aug. 14 phone call, in what Elwood considered to be a criminal referral. Demers read the transcript of the July 25 call, officials said, on August 15.

What the DOJ did next is not entirely clear. A DOJ official said it was the department’s perspective that a phone call did not constitute a formal criminal referral that allowed them to consider an investigation, and that a referral needed to be in writing.

The whistleblower was already taking separate action. On Aug. 12, he filed a complaint with the inspector general of the intelligence community, after consulting with a staff member on the House Intelligence Committee, officials said.

At the end of August, the acting director of national intelligence, Joseph Maguire, sent the Justice Department his own criminal referral based on the whistleblower complaint, he has confirmed.

Kupec says career prosecutors in the Public Integrity Section, which works on corruption cases, were involved in deciding how to proceed, as was the national security division and the Office of Legal Counsel.

A senior DOJ lawyer who briefed reporters said the department had no basis on which to open a criminal investigation because Trump’s request of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy to investigate a case involving his political opponent couldn’t amount to a quantifiable “thing of value” under campaign finance law.

DOJ officials said they focused on campaign finance law because that was how the allegations were framed in the whistleblower complaint.

“All relevant components of the department agreed with this legal conclusion,” the DOJ’s Kupec said.

Paul Seamus Ryan, vice president of policy and litigation at Common Cause, is among those questioning even the narrow campaign finance analysis. Common Cause has filed a complaint with the Justice Department and the Federal Election Commission accusing Trump of violating campaign law.

It wouldn’t have been difficult for the government to determine how much money Ukraine would have spent in an investigation of Joe Biden and his son, he said,

“That would give them a dollar amount to show that Trump solicited ‘something of value,'” Ryan said.

It’s a Mad Mad Rudy Mad World !

“The Scream” Edvard Munch

Inspiration for The Scream

Norwegian by birth, Edvard Munch studied at the Oslo Academy with famous Norwegian artist Christian Krohg. He created the first version of The Scream in 1893 when he was about 30 years old, and made the fourth and final version of The Scream in 1910. He has described himself in a book written in 1900 as nearly going insane, like his sister Laura who was committed to a mental institution during this time period as well. Personally he discussed being pushed to his limits, and going through a very dark moment in his life.

The scene of The Scream was based on a real, actual place located on the hill of Ekeberg, Norway, on a path with a safety railing. The faint city and landscape represent the view of Oslo and the Oslo Fjord. At the bottom of the Ekeberg hill was the madhouse where Edvard Munch’s sister was kept, and nearby was also a slaughterhouse. Some accounts describe that in those times you could actually hear the cries of animals being killed, as well as the cries of the mentally disturbed patients in the distance. In this setting, Edvard Munch was likely inspired by screams that he actually heard in this area, combined with his personal inner turmoil. Edvard Munch wrote in his diary that his inspiration for The Scream came from a memory of when he was walking at sunset with two friends, when he began to feel deeply tired. He stopped to rest, leaning against the railing. He felt anxious and experienced a scream that seemed to pass through all of nature. The rest is left up to an endless range of interpretations, all expressed from this one, provocative image.

The current occupant is a whiny little bitch !

The current occupant is a whiny little bitch !

Newly released texts take Trump scandal to a new level

The Rachel Maddow Show / The MaddowBlog

Quid pro quo: Newly released texts take Trump scandal to a new level

There’s a striking simplicity to the scandal that will almost certainly lead to Donald Trump’s impeachment: he used his office to try to coerce a foreign government into helping his re-election campaign. The evidence is unambiguous. More information continues to come to light, but few fair-minded observers believe the president’s guilt is in doubt.

There’s been no explicit need for Trump’s detractors to prove that his scheme included a quid pro quo – the United States would trade something of value to a foreign country in exchange for its participation in the Republican’s gambit – since Trump’s effort was itself scandalous.

But as of this morning, the quid pro quo has nevertheless been established, thanks to a series of text messages that were released overnight. NBC News reported this morning:

Text messages given to Congress show U.S. ambassadors working to persuade Ukraine to publicly commit to investigating President Donald Trump’s political opponents and explicitly linking the inquiry to whether Ukraine’s president would be granted an official White House visit.

The two ambassadors, both Trump picks, went so far as to draft language for what Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy should say, the texts indicate. The messages, released Thursday by House Democrats conducting an impeachment inquiry, show the ambassadors coordinating with both Trump’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani and a top Zelenskiy aide.

One text shows Bill Taylor, the acting U.S. ambassador in Ukraine, asking, “Are we now saying that security assistance and WH meeting are conditioned on investigations?” Apparently reluctant to acknowledge criminal wrongdoing in print, U.S. Ambassador to the European Union Gordon Sondland replied, “Call me.”

In a subsequent message, Taylor added, “As I said on the phone, I think it’s crazy to withhold security assistance for help with a political campaign.”

Just as astonishing was a message Kurt Volker, the former special U.S. envoy to Ukraine, sent to a Zelenskiy adviser shortly before the now-infamous Trump/Zelenskiy phone call. The message was clear about the White House’s political expectations, and how a presidential meeting was contingent on the Ukrainian president’s cooperation with the larger scheme.

“Heard from White House,” Volker wrote, “assuming President Z convinces trump he will investigate / ‘get to the bottom of what happened’ in 2016, we will nail down date for visit to Washington.”

The House Foreign Affairs Committee published the texts online here (pdf)

A Washington Post analysis added that the newly released messages not only document the quid-pro-quo element of the scandal, they also offer “a strong suggestion that military aid was used as leverage – and hints at an attempt to hide that.”

For two weeks, Trump’s Republican allies have argued that in order for this to be a real scandal, it would have to include a quid pro quo. That posture has long been wrong: the effort to coerce Ukraine was itself indefensible.

But what will these same GOP voices say now that the evidence has taken the scandal to the next level, meeting the one standard Republicans said had to be met?

Did Donald Trump Just Self-Impeach?

The New Yorker

On Thursday, Trump didn’t bother to contest the charge that he leaned on Ukraine to investigate Biden and his son. In fact, he did it again, live on camera, from the White House lawn. Photograph by Andrew Harnik / AP

In the ten days since the House of Representatives launched its impeachment inquiry, Presiden Trump has spoken and tweeted thousands of words in public. He has called the investigation a “coup” and the press “deranged.” He has demanded that his chief congressional antagonist, the California representative he demeans as “Liddle’ Adam Schiff,” be brought up on treason charges. He has attacked the “Do Nothing Democrats” for wasting “everyone’s time and energy on bullshit.”

There have been so many rationales coming from the President that it’s been hard to keep them straight. “How do you impeach a President who has created the greatest Economy in the history of our Country, entirely rebuilt our Military into the most powerful it has ever been, Cut Record Taxes & Regulations, fixed the VA & gotten Choice for our Vets (after 45 years), & so much more,” he complained via tweet last week, in a less-than-accurate recap of his Administration’s record. He called the charges against him a “hoax” and, quoting his lawyer Rudy Giuliani, said that he was “framed by the Democrats.” He has blamed the “#Fakewhistleblower” and the “fake news” for the impeachment investigation, which has now replaced the Mueller investigation in Trump’s rhetoric as “the Greatest Witch Hunt in the history of our country.” Trump has also insisted, over and over again, that there was nothing at all wrong with his July 25th phone call with the President of Ukraine. The call—in which he asked for the “favor” of having Ukraine investigate his 2020 political rival, the former Vice-President Joe Biden, even as he was holding up hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. military aid—triggered the impeachment inquiry in the first place. But Trump says it was “perfect.”

On Thursday morning, Trump appeared to dispense with excuses altogether, no longer even bothering to contest the charge that he leaned on Ukraine to investigate Biden and his son Hunter. How do we know this? Because Trump did it again, live on camera, from the White House lawn. In a demand that is hard to interpret as anything other than a request to a foreign country to interfere in the U.S. election, Trump told reporters that Ukraine needs a “major investigation” into the Bidens. “I would certainly recommend that of Ukraine,” the President added, shouting over the noise of his helicopter, as he prepared to board Marine One en route to Florida. He also volunteered, without being asked, that China “should start an investigation into the Bidens,” too, given that Hunter Biden also had business dealings there while his father was in office. Trump, minutes after threatening an escalation in his trade war with China, suggested that he might even personally raise the matter of the Bidens with the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping.

You could practically hear the collective gasp in Washington. Republicans had spent days denying what Trump had more or less just admitted to. “As President Trump keeps talking, he makes it more and more difficult for his supporters to mount an actual defense of his underlying behavior,” Philip Klein, the executive editor of the Washington Examiner, a conservative magazine, soon wrote. It was as though Richard Nixon in 1972 had gone out on the White House lawn and said, Yes, I authorized the Watergate break-in, and I’d do it again. It was as though Bill Clinton in 1998 had said, Yes, I lied under oath about my affair with Monica Lewinsky, and I’d do it again.

Twitter wags immediately began wondering if the President had just committed the nation’s first act of self-impeachment. On CNN, a chyron read “trump admits to very offense dems looking to impeach over.” His 2016 rival, Hillary Clinton, tweeted, “Someone should inform the president that impeachable offenses committed on national television still count.” But that is not, of course, how Trump sees it. He now faces an energized Democratic majority in the House that’s ready to impeach him for abusing his power. But with little prospect that the Republican Senate will dare to convict him and remove him from office, he isn’t even bothering to deny the facts. He’s saying, Yes, I did it—and so what?

Several weeks ago, back when Ukraine was an obscure Washington controversy about delayed military aid relegated to the inside pages of the Times, Trump already seemed to be a President on the verge of a nervous breakdown. His behavior, always erratic, had become noticeably more combative, angry, and extreme. He was hurling insults at a record pace, and he cancelled an August trip to Denmark in a fit of pique because its leader had mocked his offer to buy Greenland from her. Looking at his tweets back then, I found that Trump had amped up the volume to a striking degree, sending out hundreds more in August of this year than he had in previous summers—and many more of them were provocative, highly personal attacks on targets ranging from the “fake news” media to his Federal Reserve chairman.

Well, we hadn’t seen anything yet. Trump produced six hundred and ninety tweets in August; in September, he reached a record for his Presidency of eight hundred and one tweets, according to Factba.se, a company that tracks Trump’s statements. There were whole new bizarre episodes—remember Sharpiegate? Trump’s aborted Camp David invite to the Taliban?—and an angry parting of ways with John Bolton, his third national-security adviser. All of those incidents, of course, now seem as though they took place long ago. The sharpest spike in Trump’s tweets, not surprisingly, came late in the month, when news of the Ukraine whistle-blower’s complaint became public and congressional impeachment, until then an unlikely outcome, became a new political reality. Trump, in fact, was so publicly agitated about this swift and unexpected turn in his fortunes that the week of September 23rd was the single most active tweeting week of his Presidency. Trump sent out two hundred and forty tweets to his followers that week, easily beating his previous record of two hundred and seven, set during the week of July 7th.

Reading back over those tweets now, one can see the real-time realization by the President that, whatever he was doing, it wasn’t working. Confidence about his “perfect” call with Ukraine’s leader descended into self-pity, after he released the White House summary of the call and the controversy escalated instead of disappeared. Soon there were laments of “presidential harassment.” By September 26th, Trump was talking about “the greatest scam in the history of politics” and retweeting validation from his son, his White House counsellor, his communications director, and his congressional allies. Over the weekend and into this week, the message seemed increasingly frenetic and muddled. One minute, Trump seemed to be shoring up his Republican base and attempting to change the subject to his policy feuds with Democrats; the next, he was deep into the details of the scandal, assailing the credibility of the whistle-blower and the investigators. Again.

On Wednesday, in two separate appearances alongside the visibly uncomfortable President of Finland, Sauli Niinistö, Trump ranted in such agitated and confused fashion that the dialogue at times resembled an absurdist play:

finnish reporter: Finland is the happiest country in the world.

trump: Finland is a happy country.

finnish reporter: What can you learn from Finland?

trump: Well, you got rid of Pelosi, and you got rid of shifty Schiff. Finland is a happy country. He’s a happy leader, too.

Trump, as that exchange so memorably suggests, just can’t get over it. He can’t even formulate a sentence in public that doesn’t capture his obsessive focus on the political scandal that he created. Where previous embattled Presidents refused to discuss their plights, Trump can talk about nothing else.

The President’s ability to capture public attention, however, is diminishing. He is caught in a cycle of greater and greater rhetorical excess, a cycle that predates the Ukraine scandal but helps explain his otherwise inexplicable behavior in responding to it. According to Factba.se’s week-by-week tracking, Trump began his escalatory spiral this spring, when the special counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russia’s 2016 election interference was released. Up until that point, the President had already been notable for his aggressive use of Twitter, his combative public statements, and his hostile relationship to the truth. But, in both frequency and volume, he was significantly more muted than he has been since the Mueller report’s release. In the first two years of his Administration, there were only seven weeks when Trump tweeted more than a hundred times; since the Mueller report was made public, in April, he has done so every week except for two.

The Mueller investigation, and Trump’s festering grievance about it, appears to have shaped his public persona more than any other event of his tenure. Trump publicly proclaimed victory with the report’s release, portraying it as “complete and total exoneration.” “I won,” he said, but Trump did not take the win. Instead, he launched his Attorney General, Willian Barr, on what we know now was an international quest to investigate the origins of the Mueller investigation, pressuring U.S. allies from Britain to Italy to Australia, and also Ukraine, to unearth information that undermined the Mueller probe’s credibility. Who knows what will come out next. The impeachment investigation has just begun, and although it is starting out as tightly focused on Ukraine, we have no real idea where it might end up. What we do know about Trump, though, is unlikely to change: the restraints on him are gone, and they are not coming back.

The price paid for being Being Black in America !

Trump Is Tweeting About ‘Civil War’ and Asking for His Political Opponent to Be Arrested

Esquire

Trump Is Tweeting About ‘Civil War’ and Asking for His Political Opponent to Be Arrested

The president ventured into the insane during an hours-long tweet spasm.

THE WASHINGTON POSTGETTY IMAGES

THE WASHINGTON POSTGETTY IMAGES

It was around nine o’clock on Sunday night when the president of the United States echoed language about a “Civil War” if he is impeached and removed from office. Now, he’ll say he wasn’t calling for a civil war—he was just announcing his belief that there would be a “Civil War like fracture” if he faced consequences for violating his oath of office and betraying the national interest for his personal gain. Never mind that impeachment is a provision of the Constitution designed for removing a lawless or otherwise dangerous chief magistrate from power in a manner that comports with the law. The intent here was clear: to tie one outcome to the other, and place the idea of violent response in millions of minds across this country. The vast majority of people would never act on that, but the tweets were incitement. The message has already been received, loud and clear, by at least one right-wing paramilitary group.

Here is the diatribe trump quoted from a Fox News appearance by Robert Jeffress, one of these devoutly Evangelical pastors who talks a lot about following Jesus and also raises the prospect of violent civil war. Don’t get it twisted: there is no Civil War-like fracture without political violence, and that is what they are threatening.

Pastor Robert Jeffress: “Nancy Pelosi and the Democrats can’t put down the Impeachment match. They know they couldn’t beat him in 2016 against Hillary Clinton, and they’re increasingly aware of the fact that they won’t win against him in 2020, and Impeachment is the only tool they have to get……..rid of Donald J. Trump – And the Democrats don’t care if they burn down and destroy this nation in the process. I have never seen the Evangelical Christians more angry over any issue than this attempt to illegitimately remove this President from office, overturn the 2016……..Election, and negate the votes of millions of Evangelicals in the process. They know the only Impeachable offense that President Trump has committed was beating Hillary Clinton in 2016. That’s the unpardonable sin for which the Democrats will never forgive him………If the Democrats are successful in removing the President from office (which they will never be), it will cause a Civil War like fracture in this Nation from which our Country will never heal.”

Nothing like an endless paragraph full of triple ellipses to reassure you the world’s most powerful man is firing on all cylinders. And it continues to amaze that, three years on, we are still hearing about Hillary Clinton and 2016. The Ukraine issue concerns Trump’s conduct in office this year. It has nothing to do with the election he won despite getting fewer votes. (And never mind that, in the more recent 2018 election, Democrats absolutely routed Republicans in the House elections—not exactly an advertisement for the idea this president has the people’s mandate.) The Ukraine scandal has to do with 2016 only insofar as trump is trying to combine three separately debunked conspiracy theories to muddy the waters around what happened.

But none of these details are particularly important, since the president will soon enough be twisting or outright contradicting them to feed a constantly shifting narrative whose only steadfast feature is that he’s totally innocent and it’s actually his opponents who are traitors. Speaking of, the president also called for his political opponent to be arrested Monday morning.

It must be an incredible feeling when you see the President of the United States call for your arrest for a capital offense via some throwaway sentence fragment at the end of a tweet. Traditionally, this kind of dictatorial call for abuse of the justice system would feature in some long, impassioned speech from a balcony. In the Digital Age, however, it takes less than 280 characters to become an Enemy of the State. While Schiff did paraphrase the transcript of Trump’s call with the Ukrainian president in language that made Trump’s conduct more explicitly incriminating—a move that was unnecessary and wrong—there is no evidence he committed treason.

Make no mistake: the stakes are ramping up now, and the president’s behavior will grow increasingly erratic and dangerous. He knows full well that once he leaves office, he no longer enjoys the protection of that justice department guideline which dictates a sitting president cannot be indicted. It might be the only reason he hasn’t been. If you thought he lied before, just wait. If you thought he smeared people before, just wait. If you thought he had spasms of vicious stupidity before, just wait. And if you thought he embraced political violence before— and he has—just wait. Right-wing domestic terrorists, some of whom cited the president’s rhetoric specifically, have already engaged in sporadic acts of violence over the last few months and years.

Of course, all of this is just further reason he should be removed, along with the manifest financial corruption at the heart of his domestic and foreign policy-making thanks to his refusal to divest from his private business holdings. He is capable of anything now, and defenders of the republic will need courage in response.

How many of Trump’s minions will go down with him?

Salon

How many of Trump’s minions will go down with him: Bill Barr? Mick Mulvaney? Possibly Mike Pence?

Earlier this month, Pence met with Zelensky and promised to relay to Trump just how hard Ukraine was working to fight corruption — a term Trump has repeatedly used to explain his interest in getting Ukraine to investigate Biden and his son Hunter, who was formerly employed by a Ukrainian gas company. When Pence was asked if U.S. aid was being held up over Ukraine’s failure to investigate Biden, he acknowledged that “as President Trump had me make clear, we have great concerns about issues of corruption.” A week after Pence met with Zelensky, U.S. military aid was finally released to Ukraine.

Another Trump confidant looks to be tangled up in this sordid bullying of Ukraine as well. When Trump ordered military aid to the nation to be frozen earlier this year, he reportedly went through his acting chief of staff and budget director Mick Mulvaney, to the chagrin of Pentagon officials.

Finally, Attorney General Bill Barr appears to be most implicated by the recent revelations on Ukraine.

As Rep. Mike Quigley, D-Ill., told CNN after reading the whistleblower report Barr attempted to withhold from Congress, it appears the attorney general has once again been caught playing interference for the White House. “All I can tell you is they’re doing the very same thing here,” Quigley told CNN, comparing Barr’s rationale for blocking the whistleblower report to his summary of Robert Mueller’s report earlier this year. In his four-page summary of the Mueller report, Barr downplayed the documented episodes of Trump’s obstruction of justice, writing that he found no evidence to support criminal charges. As Barr later admitted, he had not read the Mueller report in its entirety before writing that summary.

As the White House summary of Trump’s July call with Zelensky notes (there was reportedly also an April call), the president mentioned four times that he wanted Barr to speak with the Ukrainian government about launching an investigation into Biden. As the New York Times reports, both the director of national intelligence and the inspector general of the intelligence community referred the whistleblower’s complaint about Trump’s communications to the Justice Department Curiously, Barr’s DOJ took less than a month to abandon an inquiry into Trump’s communications with Zelensky, concluding that the complaint could not even trigger an investigation because the allegations could not involve a crime.

While Barr’s DOJ released a statement denying that Barr had any contact with the Ukrainians, it is increasingly difficult to believe an attorney general who has already been held in contempt of Congress for previously faulty testimony. As Sen. Kamala Harris recalled on Wednesday, Barr previously testified under oath that he had never been directed by the president to investigate a political rival. Remarkably, a month before that, Trump told Fox News’ Sean Hannity that he ordered Barr to look into Biden’s dealings in Ukraine.

Barr, like Pence and Mulvaney, basically begged to get into Trump’s swampland. He leapt out of retirement to become one of the architects of Trump’s assault on our democracy. He is not a bumbler who was caught in the wrong place at the wrong time and was too weak to resist being corrupted. He came corrupt.

But Barr, like Trump’s personal lawyers Michael Cohen and Rudy Giuliani, doesn’t actually care about corruption. More than likely, he’s playing for the Fox News retirement plan. Every lie has told on behalf of Trump is another badge of honor.