Category: Today’s News?

Remember D-Day’s African-American Soldiers on Veterans Day

NBC News.com

Remember D-Day’s African-American Soldiers on Veterans Day

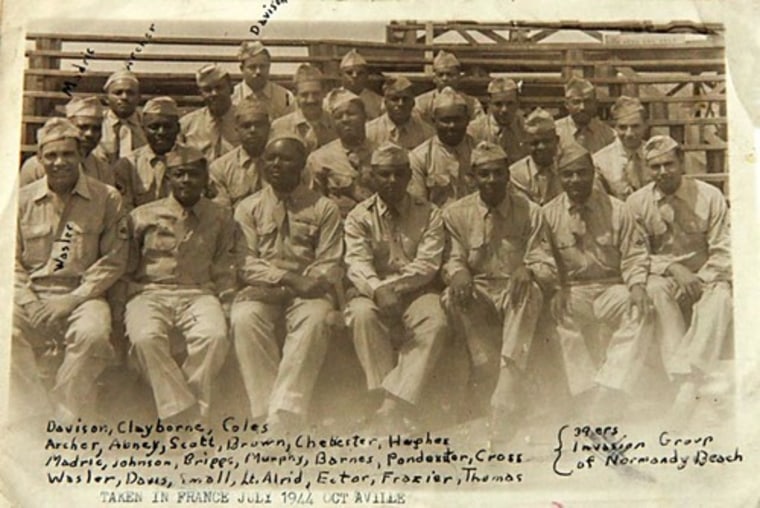

Wilson Monk (third from left) and other men from the 320th appear to be in deep thought as they peruse a document.Linda Hervieux / Wilson Monk

A few months ago I was speaking with an archivist at an Army museum who told me flatly, “There were no black men at D-Day.”

I had just explained to him that I’d spent six years researching and writing the story of D-Day’s only African-American combat unit.

The belief is pervasive that there were no soldiers of color on the beaches of France on one of the most important days of World War II. None of the many films made about D-Day like “Saving Private Ryan” show black soldiers storming Omaha Beach. Most history books don’t mention them.

It is a sore point among black veterans.

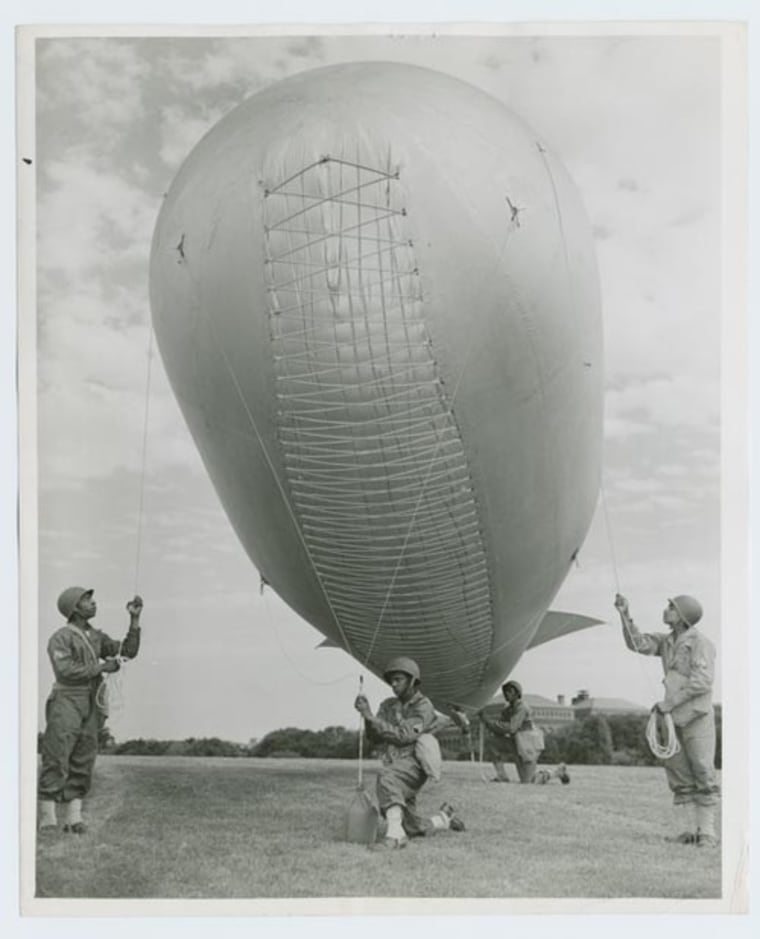

But they were there, landing under brutal fire early on June 6, 1944. The men of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion were packed tight with infantry troops aboard small metal boats that motored toward the Normandy coast obscured by smoke and fire. It was a harrowing ride, and even worse when they landed as early as 9 a.m.

They were charged with raising a curtain of hydrogen-filled balloons over the beaches anchored to steel cables. Tucked under the 125-pound gasbags were small bombs the size of a soda can. A dive-bombing German plane that hit the cable risked being blown to bits. But until the beaches were cleared of small arms fire, the balloon flyers were infantry troops. They dug trenches, rounded up German prisoners and prayed they would survive the worst day of their lives.

On this Veterans Day, it is important that we remember that the more than 1 million African Americans in uniform in WWII were ordered to fight for freedom and democracy abroad, while at home they were mistreated in an Army segregated by race.

They suffered daily humiliations at the hands of white commanders who considered them less intelligent and courageous than white men. An Army War College study concluded the black soldier “naturally believes himself inferior to the white.” This was the reason given for assigning the vast majority of black troops to labor and service units.

An Army War College study concluded the black soldier “naturally believes himself inferior to the white.” This was the reason given for assigning the vast majority of black troops to labor and service units.

By the time the sun set on June 6, 1944, some 2,000 African Americans had landed in Normandy. They were engineers, stevedores, and gunners. They carried the wounded to safety and buried the dead. They drove ambulances, earth-movers and the trucks that would supply the front lines. Black quartermasters won praise from Gen. Dwight Eisenhower for salvaging their trucks sunk in deep water — and saving significant quantities of blood plasma and medical supplies that would save lives on Omaha Beach. Eisenhower praised the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion for carrying out its mission “with courage and determination” and said the men exposed like sitting ducks on the sand “proved an important element of the air defense team.”

RELATED: 9 Things to Know About the History of Juneteenth

The Hollywood director John Ford, who landed on Omaha with a Coast Guard film crew, watched in amazement as a black soldier unloaded supplies from a ship, ignoring the small-arms fire and mortar shells pocking the sand around him. Ford was too scared to leave his safe spot to film the soldier but he wrote, “By God, if anybody deserves a medal that man does.”

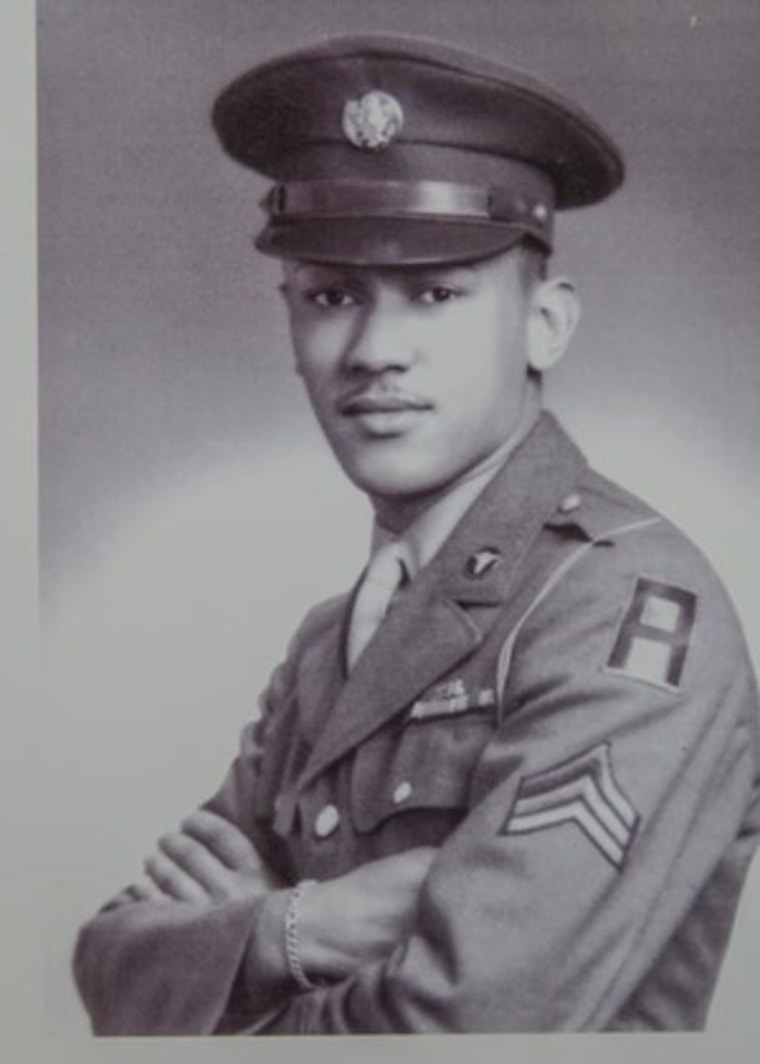

Among those brave young men steaming toward France early on D-Day was a 21-year-old medical student from West Philadelphia. Woodson didn’t wait for a draft notice. He left his studies at Lincoln University and signed up for the Army. He finished his training as a commissioned officer, but there were no positions available for him.

It was a common story: black officers in WWII were limited by quotas and the rule they not lead white officers junior to them. So he retrained as a medic with the 320th. Wounded twice as his disabled boat drifted toward Omaha, Corporal Woodson would save scores of lives until he collapsed 30 hours later. The black press dubbed him “No. 1 Invasion Hero” and Stars and Stripes wrote that Woodson and the four medics with him “covered themselves with glory on D-Day.” The black press began calling on the White House to award him the Medal of Honor.

RELATED: WWI ‘Harlem Hellfighter’ Henry Johnson to Receive Medal of Honor

A sole piece of paper exists today in the National Archives revealing that Woodson was, in fact, a candidate for the nation’s highest award for bravery. A note passed from the War Department to the White House reveals that Woodson’s commanding officer had recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest award, but that the office of a US Army general in Britain had changed the recommendation to Medal of Honor.

“This is a big enough award so that the President can give it personally, as he has in the case of some white boys,” a War Department aide wrote. The nomination was significant because no African-Americans received the Medal of Honor in World War II. After an Army study found pervasive racism was to blame for the slight and President Bill Clinton awarded seven Medals of Honor to African-Americans in 1997. Only one man was alive to shake the president’s hand.

Waverly Woodson was not among them. He had to settle for fourth place, the Bronze Star. He died in 2005 without knowing there would be another push to recognize his heroism. U.S. Rep Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) has called on the Army to approve the Medal of Honor for Woodson.

In June 2015, President Barack Obama awarded the Medal of Honor to a long-neglected hero of the trenches of France in World War I. Sgt. Henry Johnson made headlines coast to coast after single-handedly fighting off a band of Germans raiders. He was a member of New York’s 369th Infantry Regiment — the legendary Harlem Hellfighters. At a ceremony at the White House, the president recalled this long-neglected hero. “It is never too late,” he said, “to say thank you.”

Woodson’s family has begun an online petition calling for him to be awarded the Medal of Honor. For more information, go to www.lindahervieux.com.

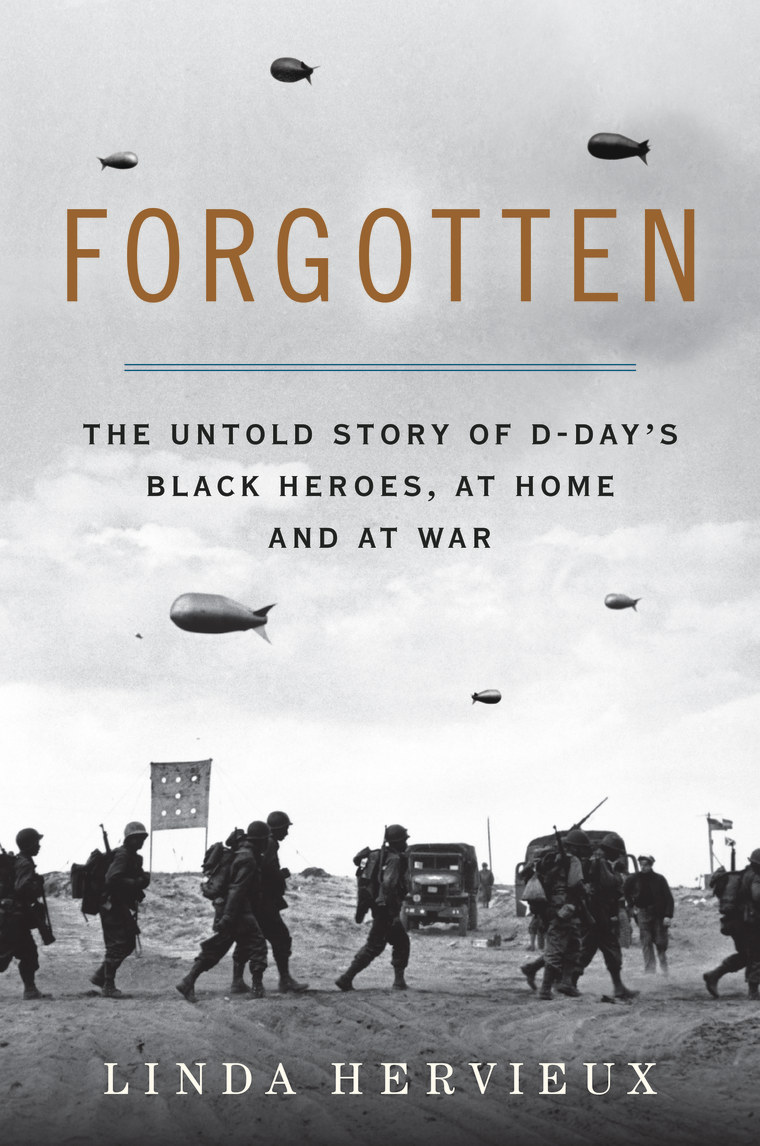

Linda Hervieux is the author of Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War (HarperCollins), which tells the story of the only African-American combat unit to land on D-Day.

A breakthrough in Eye – Ear Testing

Replace your plastic bags used in grocery shopping with these reusable produce bags

Make an impact 👉👉 http://bit.ly/322u031

Replace hundreds of plastic bags used in grocery shopping with these reusable produce bags 🌎Make an impact 👉👉 http://bit.ly/322u031

Posted by Outdoors Tribe on Friday, October 18, 2019

Microsoft (Japan) introduced a 4-day work week and productivity jumped 40%

Mind Blowing Facts

Daniel Cameron Becomes the First Black Attorney General in Kentucky.

WOW!

Daniel Cameron Becomes the First Black Attorney General in Kentucky.

“Our Gang”

Psychotic Posted a new photo to the new album “Everything”.

Northwest Family Farm Bankruptcies Increase

OPB TV – BBC Newshour

Northwest Family Farm Bankruptcies Increase

The number of family farms seeking bankruptcy protection grew 24% over the last year, according to an Ameican Farm Bureau Federation analysis of recent court data.

The analysis found family farm bankruptcies are rising fastest in the Northwest.

“We’ve seen low crop prices, low livestock prices for a number of years now,” said chief economist John Newton. “On the back, now, of that we have the trade war where agriculture’s been unfairly retaliated against.”

Newton monitors Chapter 12 bankruptcy filings as one measure of health for the farm economy. Chapter 12 is a kind of bankruptcy protection meant to help family farmers reorganize and keep farming.

Nationwide, 580 family farms filed for bankruptcy in the 12-month period ending in September 2019. Newton considers that a sign of poor health.

“While it’s nowhere near the historical highs we saw in the ‘80s, it’s an alarming trend that continues to get worse,” he said.

Newton said farmers are also assuming record debt and taking longer to pay it back.

“I’m getting calls from farmers across the country that may not be at Chapter 12 bankruptcy point, but they’re very close to it,” he said.

Thirty-three farms in the Northwest filed for Chapter 12 protection over the time period measured. Most of them were in Idaho and Montana, but the figure includes Oregon apple farmers struck by tariffs in their major export markets.

Richard and Sydney Blaine, for example, filed for Chapter 12 protection just days after President Donald Trump signed a law this summer making it easier to access. The Family Farmer Relief Act increased the amount of debt a farmer can have —$10 million — and still qualify for Chapter 12 protection.

The 33 Northwest bankruptcies represent a 74% increase over the previous year, according to the American Farm Bureau’s analysis. The size of the increase appears large in part because the Northwest previously had fewer bankruptcy filings than some other regions, such as the Midwest.

Still, economist John Newton said each Chapter 12 bankruptcy matters.

“These are family farms,” he said. “And these are family farms that are having to restructure their debt due to tough financial conditions in agriculture.”

Because of the new bankruptcy rules, more farms could seek protection in the months ahead.

Girls Won All Five Top Prizes at the Broadcom Masters STEM Competition

A Mighty Girl

For The First Time In History, Girls Won All Five Top Prizes at the Broadcom Masters STEM Competition

Posted on November 4, 2019

When the winners were announced at this year’s Broadcom MASTERS Competition, America’s premiere science and engineering competition for middle school students, the stage looked a little different than previous years — for the first time ever, all of the top prize winners were girls! 14-year-old Alaina Gassler won the top award, the $25,000 Samueli Foundation Prize, while 14-year-olds Rachel Bergey, Sidor Clare, Alexis MacAvoy, and Lauren Ejiaga each took home $10,000 prizes. “With so many challenges in our world, Alaina and her fellow Broadcom MASTERS finalists make me optimistic,” says Maya Ajmera, President and CEO of the Society for Science & the Public, which runs the competition, and Publisher of Science News. “I am proud to lead an organization that is inspiring so many young people, especially girls, to continue to innovate.”

When the winners were announced at this year’s Broadcom MASTERS Competition, America’s premiere science and engineering competition for middle school students, the stage looked a little different than previous years — for the first time ever, all of the top prize winners were girls! 14-year-old Alaina Gassler won the top award, the $25,000 Samueli Foundation Prize, while 14-year-olds Rachel Bergey, Sidor Clare, Alexis MacAvoy, and Lauren Ejiaga each took home $10,000 prizes. “With so many challenges in our world, Alaina and her fellow Broadcom MASTERS finalists make me optimistic,” says Maya Ajmera, President and CEO of the Society for Science & the Public, which runs the competition, and Publisher of Science News. “I am proud to lead an organization that is inspiring so many young people, especially girls, to continue to innovate.”

The Broadcom MASTERS — which stands for Math, Applied Science, Technology, and Engineering for Rising Stars — was founded in 2011 and aims to encourage middle school students to see how their personal passions can lead to career pathways in STEM. The competition is open to students in 6th, 7th, and 8th grades; science fairs affiliated with the Society for Science & the Public nominate the top 10% of their participants, who then apply for the chance to join the national competition. This year, there was a pool of 2,348 applicants; 30 finalists were chosen, including 18 girls and 12 boys — the first time the finalists have been majority female as well.

In this blog post, we introduce you to these clever and creative Mighty Girls and their incredible projects. Their initiatives include reducing the size of blind spots in cars, creating new methods for protecting trees from an invasive insect species, studying how to build bricks on Mars, inventing a water filter that can remove heavy metals, and researching how increased ultraviolet light from ozone depletion affects plant growth. Their innovation and curiosity is sure to inspire science-loving kids everywhere!

To encourage your Mighty Girl to see herself as a scientist, just like these competition winners, check out our blog post Ignite Her Curiosity: The Best Books to Inspire Science-Loving Mighty Girls.

Meet The Winners Of The 2019 Broadcom MASTERS

Alaina Gassler: Making Vehicles Safer By Removing Blind Spots

Alaina Gassler’s mother hates driving their Jeep Grand Cherokee: the large A-pillar design around the windshield, which provides protection in a rollover crash, also impedes her view with blind spots. The problem piqued the curiosity of the 14-year-old from West Grove, Pennsylvania: “I started to think about how blind spots are a huge problem in all cars,” she says. Alaina knew that her solution had to be inexpensive, easily accessible, and work in different lighting conditions. She created a mount for a webcam that could be installed on the passenger side A-pillar, and 3D printed a part that allowed a projector to display the image at close range inside the car. Her invention won the $25,000 Samueli Foundation Prize, but she’s not done yet: she’s already got plans to create a new prototype with an LCD screen, which is easier to see in bright light. “There’s so many car accidents and injuries and deaths that could have been prevented,” she says. “Since we can’t take [the pillar] out of cars, I decided to get rid of it without getting rid of it.”

Rachel Bergey: Trapping Invasive Insects to Protect Trees and Agriculture

In Rachel Bergey’s home in Harleysville, Pennsylvania, spotted lanternflies are a huge problem: “thousands of them have invaded my family’s maple trees,” she says. The invasive species, which is originally from Asia, damages trees and threatens over $18 billion worth of agricultural crops in Pennsylvania alone. One trap currently in use is sticky tape, but tape needs frequent replacement, doesn’t always catch the spotted lanternflies, and it can hurt helpful insects and even birds. As an alternative, Rachel came up with a trap made of a tinfoil dome with a tunnel that leads to insect netting: once the spotted lanternflies are inside, they can’t get out. When she tested it, “the tinfoil and netting trap… caught 103 percent more spotted lanternflies and 94 percent less other insects” than tape. Rachel won the $10,000 Lemelson Award for an invention that shows a promising solution to a real-world problem with her trap. She tells other young scientists to remember that most of science is hard work: “You don’t have to be super smart to be a scientist,” she says. “You just have to be observant… Hard work pays off.”

Sidor Clare: Making Bricks on Mars

Like many kids today, Sidor Clare is imagining a future Mars mission but one of her questions was how to build structures when the astronauts arrived. “Astronauts need sturdy building materials,” the Sandy, Utah native points out, “and it takes 9 months and a ton of money to ship materials to Mars.” She and her partner Kassie Holt decided to find a binding agent that would allow people to make bricks with regolith, Martian soil. The girls used Mars Global Simulant MGS-1, a soil mix that imitates the chemical and mechanical properties of regolith, and tried different binders, including polyester resin, polystyrene, and recycled high density polyethylene, or HDPE. The resin brick was the strongest — so strong that they had to use construction equipment to test it: “Our Mars resin brick can withstand more pressure than concrete.” Sidor won the $10,000 Marconi/Samueli Award for Innovation, which recognizes a young inventor with vision and promise. “A lot of people want to go to Mars,” she says, “and I wanted to help further that exploration.”

Lauren Ejiaga: Studying The Effects of Ozone Depletion

“I was always fascinated by nature,” Lauren Ejiaga says, so when she learned about how the thinning of the ozone layer let more ultraviolet rays through the atmosphere, she wondered how that change was affecting plant growth. The aspiring doctor from New Orleans, Louisiana decided to analyze the effects of increased UV radiation on plants, particularly UVB rays. She grew pansies in hollow growing cases that she built from plastic pipes and connectors. Each case had a filter that filtered UVA ray, UVB rays, or neither. She found that plants that got UVA radiation only lost 14% of their chlorophyll, the pigment that allows plants to photosynthesize, compared to her control group, while plants that got UVB radiation only lost 61% of their chlorophyll. “[Ozone depletion] affects us in more ways than what we know,” she concludes. Lauren won the $10,000 STEM Talent Award, sponsored by DoD STEM, which celebrates leadership and technical ability in STEM. She hopes to show other students that you can do science with minimal resources. “[You] don’t really need a bunch of fancy gadgets or whatever to prove that something’s happening,” she says. “They can do it in their home, their backyard. If they want to do a topic, they can go for it.”

Alexis MacAvoy: Designing Low-Cost, Eco-Friendly Water Filters

Alexis MacAvoy’s home in Hillsborough, California is near San Francisco Bay, where efforts to clean up heavy metals in the water have cost millions of dollars — a cost that could have been avoided if people had filtered their wastewater. But even today, she says, “80% of the industrial wastewater isn’t filtered whatsoever.” Activated carbon filters can effectively remove these heavy metals, and Alexis wondered if it was possible to make these filters using biowaste like coconut shells or sawdust. After testing several materials, she created filters using sawdust and walnut shells, ground to a specific mesh size and treated with sodium bicarbonate and fluoride; these filters absorbed up to 30 times more copper than a commercial filter! Alexis won the $10,000 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Award for Health Advancement for her work to make it easier to keep our water clean. She hopes her win will raise public awareness of the multiple benefits of water filtration: “preserving ecosystems so that no further damage is conducted can actually benefit our health as well.”

Mosco Mitch – Obstructing America’s Business

Attack on the Middle Class

November 7, 2019

These high-pocritical republi-con bastards in the senate then try to blame the Democratic House for doing nothing. John Hanno