Yahoo! News

California’s relentless rains affect farmworkers, strawberry prices

Ben Adler, Senior Editor – March 23, 2023

A spate of heavy rains in California that have interfered with the strawberry harvest are having a negative economic impact on farmworkers and may soon hit consumers in the wallet too.

Since December, the state has been battered by unusually heavy snows and rains, and the effects of the extreme weather — which scientists say has been exacerbated by climate change — are hurting California’s key agricultural regions.

Tricia Stever Blattler, executive director of the Tulare County Farm Bureau in the San Joaquin Valley, told ABC News on Wednesday that the state’s Central Valley is dealing with a “catastrophic level of water.”

“There’s a lot of cropland underwater right now,” Stever Blattler said. “I can’t even begin to tell you the numbers — north of 50,000 acres. Maybe closer to 75,000, 100,000.”

Acreage for growing crops including tomatoes, onions, garlic and cotton “will be diminished for a while,” she said.

On Wednesday, the Community Alliance With Family Farmers told KCRA, a TV station in Sacramento, that hundreds of thousands of acres of California farms have been affected by the latest deluge, which hit the state earlier this week.

“The area some call ‘America’s salad bowl’ more resembles a soup bowl,” a reporter on Fox Weather quipped on Sunday, in reference to inundated portions of California’s Central Valley and coast. The state grows about half of all the fruits and vegetables produced in the United States, including 91% of U.S. strawberries, according to the Department of Agriculture.

“For the farms that were flooded, this catastrophe hit at the worst possible time,” California Strawberry Commission president Rick Tomlinson said in a statement. “Farmers had borrowed money to prepare the fields and were weeks away from beginning to harvest.”

Monterey County Farm Bureau executive director Norm Groot told Fox Weather that the latest round of flooding will likely cause even more damage than the estimated $330 million crop losses from the flooding that occurred in January.

California farmworkers are also feeling the effects. Last week, more than 8,000 residents in Pajaro were forced to flee when a levee on the nearby Pajaro River broke. The community is composed largely of Latino farmworkers, and many saw their homes destroyed.

Last week, agricultural experts told the Associated Press that roughly one-fifth of strawberry farms in Watsonville and Salinas, areas near Pajaro, had been flooded. “When the water recedes, what does the field look like — if it is even a field anymore?” said Jeff Cardinale, a spokesperson for the California Strawberry Commission. “It could just be a muddy mess where there is nothing left.”

Cardinale told Bloomberg News that it’s too soon to know how much strawberry prices will be affected, but the outlet reported that they “almost are certain to rise.”

“There’s going to be an impact on national supply,” Nick Wishnatzki of Wish Farms, a berry grower that has farms all over the Americas, told Bloomberg.

Pajaro and its neighbors are just the latest in a series of California towns that were flooded this winter. In January, Fidencio Velasquez, a supervisor at Santa Clara Farms in Ventura County, told the Los Angeles Times that flooding had cost the farm upwards of $900,000 in damage to crops and equipment, and that 150 of its employees would be furloughed for weeks.

Thousands of residents of Planada, an agricultural community an hour west of Yosemite National Park, saw their homes and cars laid to waste in January by a series of dramatic rainfall events. Now they must rebuild at a time when flooded fields cannot be harvested, crops are rotting and the workers have no income.

“The very workers who put food on our table are getting hot meals from the Salvation Army,” Antonio De Loera-Brust, a spokesperson for the United Farm Workers of America, told the New York Times in late February. “Whether California is on fire or underwater, the farmworkers are always losing.”

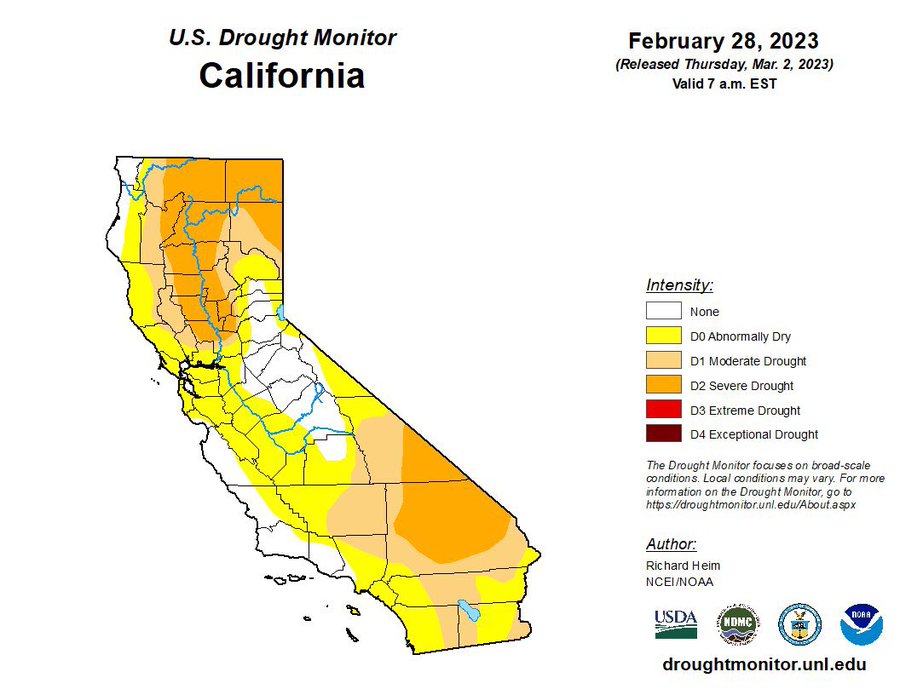

Wildfires and floods are both becoming more severe because of climate change. As UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain recently explained to Yahoo News, warmer temperatures are causing more evaporation, resulting in more moisture in the Earth’s atmosphere. But climate change is also increasing the likelihood of droughts.

Intense heat waves have led to worse wildfire seasons throughout the West in recent years. Smoke from those fires can destroy crops — ruining the taste of grapes, for example. Inhalation of wildfire smoke is also harmful to farmworkers, and working in extreme heat is a growing health hazard.

“We have compounding and cascading disasters from extreme storms, flooding, wildfires, heat waves and drought that are all impacting farmworkers,” Michael Méndez, assistant professor of environmental planning and policy at the University of California, Irvine, told the Los Angeles Times.