Salon – Opinion

Trump’s CPAC speech showed clear signs of major cognitive decline — yet MAGA cheered

Chauncey DeVega – February 26, 2024

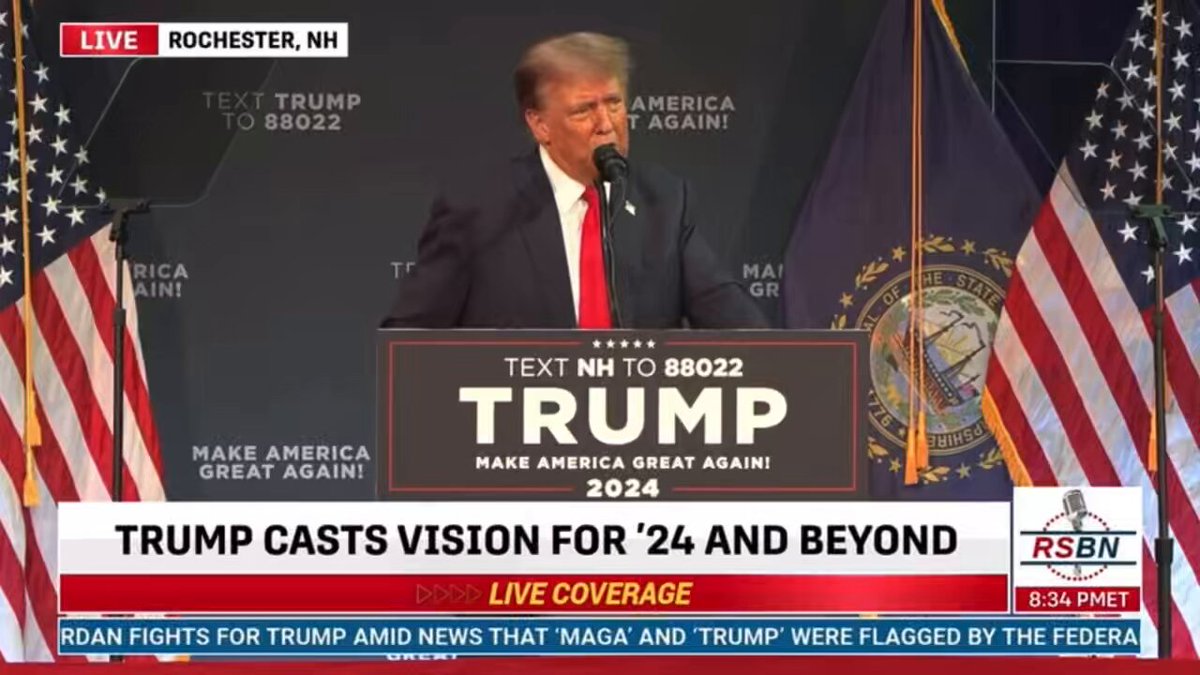

Donald Trump was in his full glory over the weekend at the annual Conservative Political Action Committee (CPAC) conference. For his MAGA people, Republicans, and other neofascists and followers, Trump is like a father figure, preacher, teacher, confessor, lover, and god messiah prophet all in one person. In that way, CPAC is Donald Trump’s “church family” – only the church is full of fascism, hatred, wickedness, cruelty, and other anti-human values, beliefs, and behavior. Trump masterfully wields and conducts this energy.

Donald Trump’s speech at this year’s CPAC was truly awesome. As used here, “awesome” does not mean good, but instead draws on the word’s origins as in “inspiring awe or dread.” In his keynote speech on Saturday, Trump said that America is on a “fast track to hell” under President Biden and the Democrats and that “If crooked Joe Biden and his thugs win in 2024, the worst is yet to come. Our country will sink to levels that are unimaginable.”

He continued with his Hitler-like threats of an apocalyptic end-times battle between good and evil and that the country would be destroyed if he is not installed in the White House. Of course, Trump continued to amplify the Big Lie about the 2020 election being “stolen” from him and the MAGA people. He also made great use of the classic propaganda technique, as though he learned it personally from Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels: Accuse your opposition of that which you are guilty of.

The New York Times detailed Trump’s ominous speech as follows:

If Mr. Biden is re-elected for a second four-year term, Mr. Trump warned in his speech, Medicare will “collapse.” Social Security will “collapse.” Health care in general will “collapse.” So, too, will public education. Millions of manufacturing jobs will be “choked off into extinction.” The U.S. economy will be “starved of energy” and there will be “constant blackouts.” The Islamist militant group Hamas will “terrorize our streets.” There will be a third world war and America will lose it. America itself will face “obliteration.”

On the other hand, Mr. Trump promised on Saturday that if he is elected America will be “richer and safer and stronger and prouder and more beautiful than ever before.” Crime in major cities? A thing of the past.

“Chicago could be solved in one day,” Mr. Trump said. “New York could be solved in a half a day there.”

Donald Trump has repeatedly shown himself to be a malignant narcissist and white victimologist. In his CPAC speech, he compared himself to pro-democracy activist Alexei Navalny, who died under the authority of Putin’s regime last week. Trump also continued to threaten his and the MAGA movement’s “enemies” with prison or worse as they meet their “judgment day”:

“I stand before you today not only as your past and future president, but as a proud political dissident….“For hard-working Americans Nov. 5 will be our new liberation day — but for the liars and cheaters and fraudsters and censors and impostors who have commandeered our government, it will be their judgment day…. Your victory will be our ultimate vindication, your liberty will be our ultimate reward and the unprecedented success of the United States of America will be my ultimate and absolute revenge.”

Here, Donald Trump sounded like an evil version of President Thomas Whitmore in the 1996 movie “Independence Day.”

He also used stochastic terrorism to encourage violence by his MAGA followers and other supporters with the lie that they are somehow being “victimized” or “persecuted” in America: “I can tell you that weaponized law enforcement hunts for conservatives and people of faith.” Echoing those themes, Trump, who believes that he is above and outside the rule of law, described his finally being held responsible for his many obvious crimes against American democracy and society as “Stalinist Show Trials,” as The Guardian further details:

Facing 91 criminal charges in four cases, Trump projected himself as both martyr and potential saviour of the nation. “A vote for Trump is your ticket back to freedom, it’s your passport out of tyranny and it’s your only escape from Joe Biden and his gang’s fast track to hell,” he continued.

“And in many ways, we’re living in hell right now because the fact is, Joe Biden is a threat to democracy – really is a threat to democracy.”

Speaking days after the death of the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, Trump hinted at a self-comparison by adding: “I stand before you today not only as your past and hopefully future president but as a proud political dissident. I am a dissident.”

The crowd whooped and applauded. Trump noted that he had been indicted more often than the gangster Al Capone on charges that he described as “bullshit”. The audience again leaped to their feet, some shaking their fists and chanting: “We love Trump! We love Trump!”

Trump argued without evidence: “The Stalinist show trials being carried out at Joe Biden’s orders set fire not only to our system of government but to hundreds of years of western legal tradition.

“They’ve replaced law, precedent and due process with a rabid mob of radical left Democrat partisans masquerading as judges and juries and prosecutors.”

Trump is an expert on leveraging everyday people’s pain points and personal fear. In his CPAC speech, Trump triggered this by focusing on real economic anxieties and feelings of vulnerability and precarity about rising energy costs, the cost of living, and the “American Dream” more broadly.

To this point, President Biden and the Democrats have not been able to effectively counter such attacks by Donald Trump and his spokespeople and other agents. Appeals to the facts about how historically great Biden’s economy is, are no salve for how everyday people are experiencing hardship and increasingly view Donald Trump and Trumpism as a viable alternative to the Democrats and “democracy.”

Trump also spun up a horror story version of the United States as a country overrun by black and brown migrants and “illegal” immigrants who are like the cannibalistic serial killer Hannibal Lecter from the film “Silence of the Lambs.” Trump’s solution: mass deportations and concentration camps.

During his speech, Donald Trump would continue to valorize the Jan. 6 terrorists who attacked the Capitol as fascist saints and martyrs of the MAGA movement – a group who Trump vowed to pardon when/if he takes power in 2025. They will in turn become his personal shock troops. Trump’s megalomania and claims to god-like power, were on full display during his speech on Saturday, where the ex-president, described himself in the third person, telling the audience that “Trump was right about everything.”

In an excellent article at Mother Jones, Stephanie Mencimer shared what she learned from embedding herself at last week’s CPAC conference (she did not attend as a credentialed reporter) and how in the Age of Trump and American neofascism that event is a festival of extreme right-wing politics and the hatred and intolerance that are among its most defining features:

Exiled from the press pen, I was just part of the audience, a space previously off-limits to reporters. To say the least, it was enlightening. On Friday, for instance, I listened to a main-stage speech from Chris Miller, a Republican running for governor of West Virginia. Because of its tax-exempt status, CPAC bans speakers from openly campaigning there, so he was listed on the program simply as “businessman.”

Like virtually every other speaker at the event, Miller devoted several of his allotted five minutes to railing against transgender healthcare. “Woke doctors are literally making boys into girls,” he declared. “They’re practicing mutilation, not medicine. They should be in prison.” At that point, a burly man in a giant black cowboy hat sitting next to me leaned over conspiratorially and proclaimed, “I think we should hang them all! I really do.” And he laughed like we were in on the same joke. I confess that I was too cowardly to tell him I was with the left-wing fake news.

Later, during a speech by South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem, I was sitting next to a woman in full-on MAGA gear. When Noem declared, “There are some people who love America, and there are some people who hate America,” my neighbor gave me a small heart attack. “Get the FUCK OUT!” she yelled furiously, ready to rumble. “Get the FUCK OUT!” Meanwhile, the old man in the camo Trump hat next to her had somehow fallen asleep.

Mencimer then reflected on the devolution of CPAC, describing it as, “[W]hat passed for policy discussions at CPAC this year was largely limited to mass deportations and attacks on trans athletes. The sober panels about the national debt, balancing the budget, or Social Security reform that once commanded top billing were a relic of another era before CPAC became an extension of Trump Inc., devoted to all the MAGA grievances like racial equity, the evils of windmills, or bans on gas stoves.”

During his CPAC speech, Trump continued with his often incoherent and confused way of speaking, rambling(s), memory lapses, and extreme tangents. Trump defended his apparent speech challenges, saying that, “And by the way, isn’t this better than reading off a fricking teleprompter…’They’ll say: he rambled. Nobody can ramble like this….Probably I won’t get the best speaker this year because I went off this stupid teleprompter.”

Trump’s CPAC speech appears to be further evidence of what psychiatrist John Gartner concluded “appears to be … gross signs of dementia. This is a tale of two brains. Biden’s brain is aging. Trump’s brain is dementing.”

However, one must be cautious and understand that Trump’s apparent mental, emotional, and overall cognitive decline, and other indications of a damaged mind, are largely irrelevant to his followers. Donald Trump is a symbol more than a man. His MAGA people and other loyalists and voters ignore, reconcile, and more generally make sense of Trump’s apparent cognitive and speech difficulties by telling themselves that he is “just like them” and “speaks a language they can understand” because he is “authentic” and “not a traditional politician.” By definition, the Dear Leader is infallible. Fake right-wing populism can be bent and shaped to accommodate any absurdity.

Donald Trump’s speech at CPAC is but more evidence that he is giving his MAGA people and other followers and supporters in the Republican Party and the larger right-wing and “conservative” movement what they want. Public opinion polls and other research have consistently shown that there are tens of millions of Americans who yearn for an American dictator or others strongman-type leader, who will “break the rules” to “get things done” for “people like them.” In addition, Republican and other Trump voters specifically support his taking power as a dictator and ending democracy. And as has been widely documented, a significant percentage of white voters do not support democracy if it means that their “racial” group does not have the most influence and power and privilege in American society as compared to black and brown people.

Donald Trump and today’s Republican Party and the larger right-wing and neofascist movement have successfully tapped into what is a centuries-old vein of white supremacist herrenvolk nightmare dreams and white rage in American society and life. The CPAC conference featured speakers and panels that reinforced that today’s Republican Party and “conservative movement” have rejected multiracial pluralistic democracy and seek to replace it with a White Christofascist Apartheid plutocracy.

In contrast to Donald Trump’s awfully awesome speech at CPAC on Saturday, President Biden solemnly warned reporters, again, that the 2024 Election is an existential battle for the country’s democracy and the soul of the nation where our most fundamental freedoms as Americans are imperiled.

In a recent essay here at Salon, Brian Karem reflected on his personal experience with such peril:

The most disturbing thing I’ve ever heard a president say did not come from Donald Trump.

It came from Joe Biden. Speaking with reporters in California on Thursday, the president said this about Donald Trump. “Two of your former colleagues not at the same network personally told me if he wins, they will have to leave the country because he’s threatened to put them in jail,” Biden told Katie Couric. “He embraces political violence,” Biden said of Trump “No president since the Civil War has done that. Embrace it. Encourages it.”

Perhaps I should have been shocked at the revelation that Trump, should he return to power, would jail reporters. I wasn’t of course. I had to fight him (and beat him) three times in court during his first administration to keep my White House press pass. I had already privately heard Trump’s threats. It was just disturbing to hear Joe Biden confirm it publicly. …

That is why the world cannot see Trump back in the White House. He knows nothing but divisiveness. And Biden was right to point out that Trump wants to jail reporters.

Trump supporters don’t care. But I’ve eaten Texas jail food, so I do.

When Einstein fled Germany he fled the poison of nationalism and longed for a country of civil liberty and tolerance. The closest he found was here in the United States. Where is it today? More importantly, where will it be after the November general election?

As always, believe the autocrat-dictator or other such political thug. He or she – in this case Donald Trump – is not kidding or joking.

Echoing Karem’s experience, I have talked to members of the pro-democracy movement (specifically journalists and reporters), and they have shared with me how they are in the process of deciding if they will stay here in the United States or flee the country if Dictator Trump and his regime takes power in 2025.

On Election Day, which will be here very soon, the American people have a choice to make. Last weekend’s CPAC conference was just one more escalation in the direct and transparent threats and dangerousness of Trumpism and American neofascism. If Trump wins on Election Day, the American people cannot say they were surprised by the hell he and his regime and followers will unleash on the country. The American people were told repeatedly what would happen and through both their active and tacit support for Trumpism and neofascism (indifference or otherwise not voting for President Biden and by implication American democracy in this decisive moment) allowed it to happen. How great is the American people’s drive to self-destruction? We will soon find out in eight or so months.