Associated Press

House GOP pushes Hunter Biden probe despite thin majority

Colleen Long – November 18, 2022

WASHINGTON (AP) — Even with their threadbare House majority, Republicans doubled down this week on using their new power next year to investigate the Biden administration and, in particular, the president’s son.

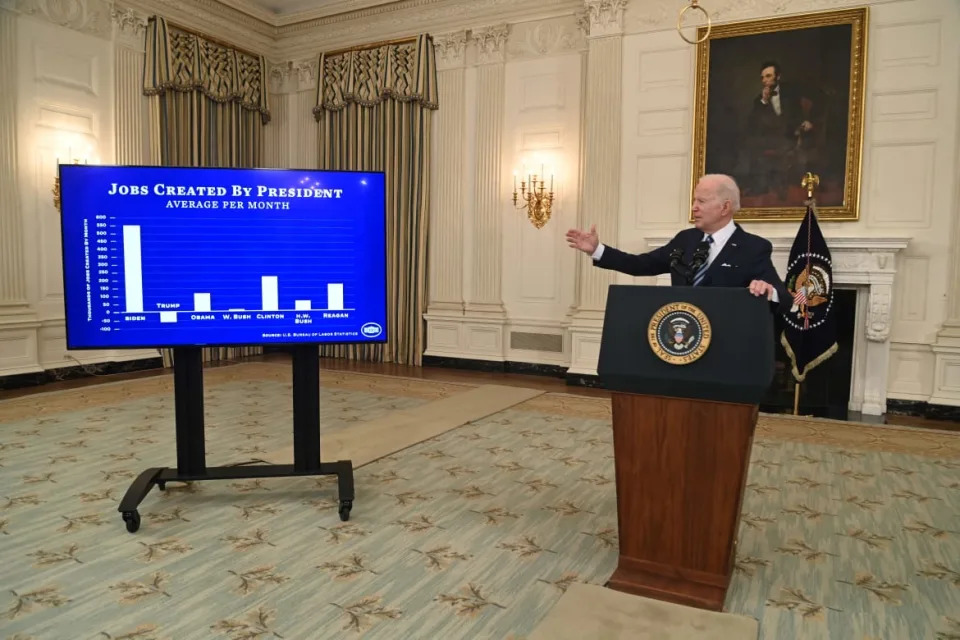

But the midterm results have emboldened a White House that has long prepared for this moment. Republicans secured much smaller margins than anticipated, and aides to President Joe Biden and other Democrats believe voters punished the GOP for its reliance on conspiracy theories and Donald Trump-fueled lies over the 2020 election.

They see it as validation for the administration’s playbook for the midterms and going forward to focus on legislative achievements and continue them, in contrast to Trump-aligned candidates whose complaints about the president’s son played to their most loyal supporters and were too far in the weeds for the average American. The Democrats retained control of the Senate, and the GOP’s margin in the House is expected to be the slimmest majority in two decades.

“If you look back, we picked up seats in New York, New Jersey, California,” said Mike DuHaime, a Republican strategist and public affairs executive. “These were not voters coming to the polls because they wanted Hunter Biden investigated — far from it. They were coming to the polls because they were upset about inflation. They’re upset about gas prices. They’re upset about what’s going on with the war in Ukraine.”

But House Republicans used their first news conference after clinching the majority to discuss presidential son Hunter Biden and the Justice Department, renewing long-held grievances about what they claim is a politicized law enforcement agency and a bombshell corruption case overlooked by Democrats and the media.

“From their first press conference, these congressional Republicans made clear that they’re going to do one thing in this new Congress, which is investigations, and they’re doing this for political payback for Biden’s efforts on an agenda that helps working people,” said Kyle Herrig, the founder of the Congressional Integrity Project, a newly relaunched, multimillion-dollar effort by Democratic strategists to counter the onslaught of House GOP probes.

Inside the White House, the counsel’s office added staff months ago and beefed up its communication efforts, and staff members have been deep into researching and preparing for the onslaught. They’ve worked to try to identify their own vulnerabilities and plan effective responses. But anything the House seeks related to Hunter Biden, who is not a White House staffer, will come from his attorneys, who have declined to respond to the allegations.

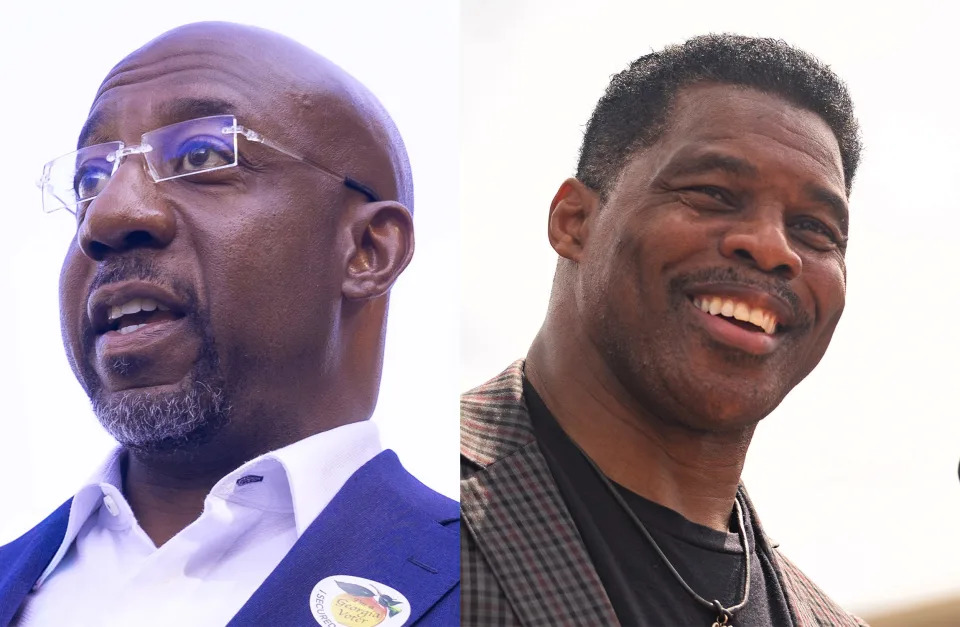

Rep. James Comer, incoming chairman of the House Oversight Committee, said there are “troubling questions” of the utmost importance about Hunter Biden’s business dealings and one of the president’s brothers, James Biden, that require deeper investigation. He said they were examining the president, too.

“Rooting out waste, fraud and abuse in the federal government is the primary mission of the Oversight Committee,” said Comer, R-Ky. “As such, this investigation is a top priority.”

Republican legislators promised a trove of new information this past week, but what they have presented so far has been a condensed review of a few years’ worth of complaints about Hunter Biden’

Hunter Biden joined the board of the Ukrainian gas company Burisma in 2014, around the time his father, then vice president, was helping conduct the Obama administration’s foreign policy with Ukraine. Senate Republicans have said the appointment may have posed a conflict of interest, but they did not present evidence that the hiring influenced U.S. policies, and they did not implicate Joe Biden in any wrongdoing.

Republican lawmakers and their staff for the past year have been analyzing messages and financial transactions found on a laptop that belonged to Hunter Biden. They long have discussed issuing congressional subpoenas to foreign entities that did business with him, and they recently brought on James Mandolfo, a former federal prosecutor, to assist with the investigation as general counsel for the Oversight Committee.

The difference now is that Republicans will have subpoena power to follow through.

“The Republicans are going to go ahead,” said Tom Davis, a Republican lawyer who specializes in congressional investigations and legislative strategy. “I think their members are enthusiastic about going after this stuff … there are a lot of unanswered questions. Look, the 40-year trend is parties under-investigate their own and over-investigate the other party. It didn’t start here.”

White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre dismissed the GOP focus on investigations as “on-brand” thinking.

“They said they were going to fight inflation, they said they were going to make that a priority, then they get the majority and their top priority is actually not focusing on the American family, but focusing on the president’s family,” she said.

Even some newly elected Republicans are pushing back against the idea.

“The top priority is to deal with inflation and the cost of living. … What I don’t want to see is what we saw in the Trump administration, where Democrats went after the president and the administration incessantly,” Rep.-elect Mike Lawler of New York said on CNN.

Hunter Biden’s taxes and foreign business work are already under federal investigation, with a grand jury in Delaware hearing testimony in recent months.

While he never held a position on the presidential campaign or in the White House, his membership on the board of the Ukrainian energy company and his efforts to strike deals in China have long raised questions about whether he traded on his father’s public service, including reported references in his emails to the “big guy.”

Joe Biden has said he’s never spoken to his son about his foreign business, and there are no indications that the federal investigation involves the president.

Trump and his supporters, meanwhile, have advanced a widely discredited theory that Biden pushed for the firing of Ukraine’s top prosecutor to protect his son and Burisma from investigation. Biden did indeed press for the prosecutor’s firing, but that was a reflection of the official position of not only the Obama administration but many Western countries and because the prosecutor was perceived as soft on corruption.

House Republicans also have signaled upcoming investigations into immigration, government spending and parents’ rights. White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, Attorney General Merrick Garland and FBI Director Chris Wray have been put on notice as potential witnesses.

Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio, incoming Judiciary Committee chairman, has long complained of what he says is a politicized Justice Department and the ongoing probes into Trump.

On Friday, Garland appointed a special counsel to oversee the Justice Department’s investigation into the presence of classified documents at Trump’s Florida estate as well as key aspects of a separate probe involving the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection and efforts to undo the 2020 election.

Trump, in a speech Friday night at his Mar-a-Lago estate, slammed the development as “the latest in a long series of witch hunts.”

Of Joe and Hunter Biden, he asked, “Where’s their special prosecutor?”

Matt Mackowiak, a Republican political strategist, said it’s one thing if the investigations into Hunter Biden stick to corruption questions, but if it veers into the kind of mean-spirited messaging that has been floating around in far-right circles, “I don’t know that the public will have much patience for that.”

Associated Press Writer Eric Tucker contributed to this report.