Chicago Suntimes

Lost Cause marches on, 1861 to now

Futile open rebellion goes back to the Confederacy. Trump will also lose, but will also keep fighting.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/68622974/620870614.0.jpg)

The South was never going to win the Civil War.

If you consider the resources of the North, the moment the first Confederate cannon fired on Fort Sumter, the South’s doom was sealed. A week later, the Chicago Tribune ran a prescient editorial explaining why.

“It is a military maxim of modern war that the longest purse wins,” it begins, outlining the North’s advantages in manpower, manufacturing, maritime strength and, most of all, money. “The little State of Massachusetts can raise more money than the Jeff Davis Confederacy.”

The conclusion may have been foregone, but it took four years and 620,000 American lives to play out.

It’s still unfolding. The Confederacy lost the war, but never gave up the fight — its baked-in bigotry, the proud ignorance required to consider another human being your property, marches on, from then to now. Manifesting itself plainly in the Trump era, his entire political philosophy being the slaveholder mentality decked out in new clothes, trying to pass in the 21st century. They even wave the same rebel flag. Kind of a giveaway, really.

The Lost Cause marches on, as we will see Wednesday, when Congress faces another ego-stoked rebellion: Donald Trump’s insistence that his clearly losing the 2020 presidential election in the chill world of fact can be set aside, since he won the race in the steamy delta swampland between his ears.

No way. Not as long as there are Americans, like the Chicagoans rushing to sign up to fight in April 1861, who are true patriots and willing to stand up for democracy.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22215366/Trump_supporters_Confederate_flag.jpg)

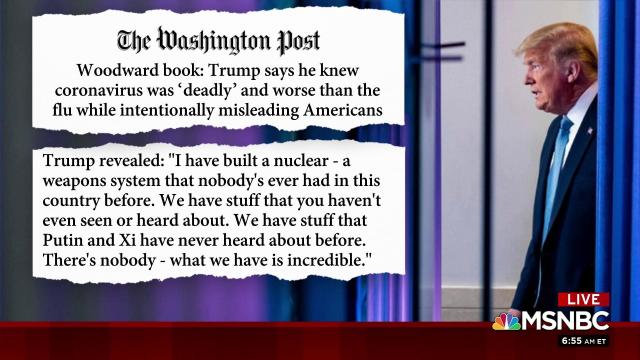

While trying to thwart the will of the people, the president has, for the past two months, ignored a lethal pandemic raging across the country — one whose toll over two years may match the Civil War’s over four. Aided by Republican politicians in open rebellion to the Constitution and the laws of this country. And millions of Americans who support him because, like the slave-holding South, they have made a fundamental error in judgment. They believe their own self-aggrandizing delusions, convinced their opponents will collapse at a touch.

Almost exactly 160 years ago, the smaller, weaker South thought it could impose its will on the whole country by military force. During the past four years Trump, who received 10 million fewer votes than his opponents in two presidential elections, served not America, but only his fanatical base. Never forget the Trump administration initially tried to shrug off COVID as a blue state problem.

The South expected the Northern population to rebel with them, against their own government. Like today, their warped worldview was stoked by the media.

“This preposterous idea has been instilled into their noddles from reading such satanic and tory sheets as the New York Herald and Chicago Times,” the Trib editorialized, “which they were led to suppose reflected Democratic opinion in the Free States.”

(The copperhead Chicago Times, I hasten to point out, is no relation to the paper you’re reading now. It folded in 1901. Our forefather, the Chicago Daily Times, began in 1929.)

The South figured out how, in losing, to win, after a fashion. They waited out the federal troops of Reconstruction, then returned to slavery, barely altered and under a new name, keeping Blacks down in economic and legal bondage. For 100 years. First slaves couldn’t vote. Then Blacks in the South were kept from voting. And today the president tries to bat Black votes away, if not for him.

The fight continues. In the spring of 1861, the Tribune called the Southern secession “the most senseless and causeless rebellion of all history.” Until now. We may have surpassed it with Trump’s frantic tearing at our democracy, supported by a cast of cowards and traitors, hailed by the eternally duped. And for what? Lower taxes? A wall? Their fetus friends? An embassy in Jerusalem? I will never understand it.

No matter. They’re losers. They lost in 1865, lost in 2020. Evil always loses, eventually. Since they continue to fight, desperate to go back to the plantations of their dreams, they’ll continue to lose. Not every battle. But their war against the future is futile, doomed. Drowned out by the swelling ranks of diverse, accepting Americans, facing actual problems with courage and candor, dedicated to helping our nation become what she is destined to be.