CBS 60 Minutes

Chip shortage highlights U.S. dependence on fragile supply chain

Seventy-five percent of semiconductors, or microchips — the tiny operating brains in just about every modern device — are manufactured in Asia. Lesley Stahl talks with leading-edge chip manufacturers, TSMC and Intel, about the global chip shortage and the future of the industry.

Lesley Stahl August 29, 2021

Car companies across the globe have had to idle production and workers because of a shortage of semiconductors, often referred to as microchips or just chips. They’re the tiny operating brains inside just about every modern device, like smartphones, hospital ventilators, even fighter jets. As we first reported in May, the pandemic sent chip demand soaring unexpectedly, as we bought computers and electronics to work, study, and play from home. But while more and more chips are needed in the U.S., fewer and fewer of them are manufactured here.

Intel is the biggest American chipmaker. Its most advanced fabrication plant, or fab for short, is located outside Phoenix, Arizona. New CEO, Pat Gelsinger, invited us on a tour to see how incredibly complex the manufacturing process is.

First, we had to suit up to avoid contaminating the fab: head-cover – on; bunny suit – zipped; goggles; gloves… ready to go.

Lesley Stahl: I’m pristine!

Pat Gelsinger: Everything in this environment is controlled.

Together we stepped into a place with some of the most sophisticated new technology on Earth.

Lesley Stahl: I need to ask you why we’re all yellow?

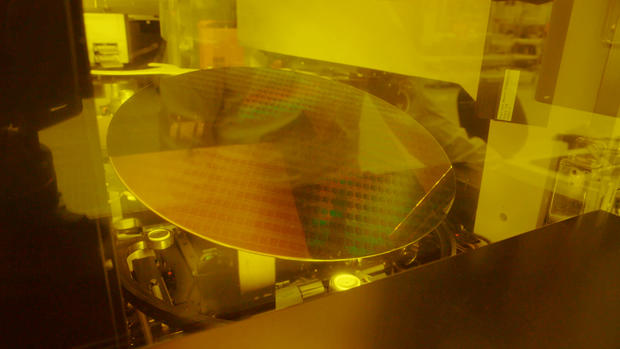

Yellow filters remove light-rays that are harmful to the process. Overhead a computerized highway transports materials from one machine to the next. The process involves thousands of steps, where layer upon layer of microscopic circuitry is etched onto these silicon plates – that are then chopped up into chips that will end up in, say, your computer. Making just one can take six months.

Pat Gelsinger: You see, each one of these is a chip.

Lesley Stahl: Is a chip. I’m surprised. I thought chips were minute.

Pat Gelsinger: Well, each one of these chips has maybe a billion transistors on it.

Lesley Stahl: Oh, my goodness!

Pat Gelsinger: So there’s billion little circuits inside of it that are all on one of these chips. And then one wafer could have 100 or 1,000 chips on it.

Intel’s goal is to keep shrinking the transistors’ size, so you can pile more of them on a chip to make it more powerful and work faster.

Pat Gelsinger: Every one of these is laying down circuits that are so much smaller than anything, your hair, you know, any other part of human existence. You know, a COVID particle is way bigger than one of the lines that we’re creating here.

Lesley Stahl: How much does this fab cost?

Pat Gelsinger: $10 billion dollars.

Lesley Stahl: Billion??

Pat Gelsinger: $10 billion ’cause each one of these pieces of equipment is maybe $5 million. That’s a lot of millions of dollars.

Chips differ in size and sophistication depending on their end-use. Intel doesn’t presently make many chips for the auto-sector but because of the shortage it’s planning to reconfigure some of its fabs to start churning them out.

Lesley Stahl: I’m wondering, if we’re going to continue to have shortages, not just in cars, but in our phones and for our computers, for everything?

Pat Gelsinger: I think we have a couple of years until we catch up to this surging demand across every aspect of the business.

COVID showed that the global supply chain of chips is fragile and unable to react quickly to changes in demand. One reason: fabs are wildly expensive to build, furbish, and maintain.

Lesley Stahl: it used to be that there were 25 companies in the world that made the high-end, cutting-edge chips. And now there are only three. And in the United States? – You.

GELSINGER HOLDS UP FINGER

Lesley Stahl: One. One.

Today, 75% of semiconductor manufacturing is in Asia.

Pat Gelsinger: 25 years ago, the United States produced 37% of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S. Today, that number has declined to just 12%.

Lesley Stahl: Doesn’t sound good.

Pat Gelsinger: It doesn’t sound good. And anybody who looks at supply chain says, “That’s a problem.”

A problem because relying on one region, especially one as unpredictable as Asia, is highly risky. Intel has been lobbying the U.S. government to help revive chip manufacturing at home – with incentives, subsidies, and-or tax breaks, the way the governments of Taiwan, Singapore, and Israel have done. The White House is responding, proposing $50 billion for the semiconductor industry in the U.S. as part of President Biden’s infrastructure plan.

Lesley Stahl: Your business is extremely lucrative. In terms of revenue, you made $78 billion last year. Why should the government come in to a company, a business that’s doing so well overall?

Pat Gelsinger: This is a big, critical industry and we want more of it on American soil: the jobs that we want in America, the control of our long term technology future, and as we’ve also said, the disruptions in the supply chain.

Lesley Stahl: You have spent much more in stock buybacks than you have in research and development. A lot more.

Pat Gelsinger: We will not be anywhere near as focused on buybacks going forward as we have in the past. And that’s been reviewed as part of my coming into the company, agreed upon with the board of directors.

Lesley Stahl: Why shouldn’t private industry fund this instead of the government? The industries that rely on these chips – Apple, Microsoft, the companies that are rolling in money?

Pat Gelsinger: Well, they’re pretty happy to buy from some of the Asian suppliers.

Actually, they don’t always have a choice. For chips with the tiniest transistors – there is no “made in the U.S.” option. Intel currently doesn’t have the know-how to manufacture the most advanced chips that Apple and the others need.

Lesley Stahl: The decline in this industry. It’s kinda devastating, isn’t it?

Pat Gelsinger: The fact that this industry was created by American innovation–

Lesley Stahl: The whole Silicon Valley idea started with Intel.

Pat Gelsinger: Yeah… The company stumbled. You know, it’s still a big company – we had some product stumbles, some manufacturing and process stumbles.

Perhaps the biggest stumble was in the early-2000s, when Steve Jobs of Apple needed chips for a new idea: the iPhone. Intel wasn’t interested. And Apple went to Asia, eventually finding TSMC: the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company – today, the world’s most advanced chip-manufacturer, producing chips that are 30% faster and more powerful than Intel’s.

Lesley Stahl: They’re ahead of you on the manufacturing side.

Pat Gelsinger: Yeah.

Lesley Stahl: Considerably ahead of you.

Pat Gelsinger: We believe it’s gonna take us a couple of years and we will be caught up.

Gelsinger is making big bets: breaking ground on two new giant fabs in Arizona, costing $20 billion; Intel’s largest investment ever. And he announced in May a three and a half billion dollar upgrade of this fab in New Mexico.

But TSMC is a manufacturing juggernaut worth over a half a trillion dollars. Collaborating with clients to produce their chip designs, it’s been sought out by Apple, Amazon, contractors for the U.S. military, and even Intel, which uses TSMC to produce its cutting-edge designs they’re not advanced enough to make themselves.

Lesley Stahl: How and why did Intel fall behind?

Mark Liu: It is surprising for us too.

We spoke remotely with TSMC chairman Mark Liu at the company headquarters in Hsinchu, Taiwan. His company is a leading supplier of the chips that go into American cars. In March, 2020, as COVID paralyzed the U.S. – car sales tumbled, leading automakers to cancel their chip orders so TSMC stopped making them. That’s why when car sales unexpectedly bounced back late last year there was a shortage of chips: leaving cars with no power parked in carmakers’ lots – costing them billions.

Mark Liu: We heard about this shortage in December timeframe. And in January, we tried to squeeze as more chip as possible to the car company. There’s a time lag. In car chips particularly, the supply chain is long and complex. The supply takes about seven to eight months.

Lesley Stahl: Should Americans be concerned that most chips are being manufactured in Asia today?

Mark Liu: I understand their concern, first of all. But this is not about Asia or not Asia I mean, the shortage will happen no matter where the production is located because it’s due to the COVID.

Lesley Stahl: But Pat Gelsinger at Intel talks about a need to rebalance the supply chain issue because so much, so many of the chips in the world now are made in Asia.

Mark Liu: I think U.S. ought to pursue to run faster, to invest in R&D, to produce more Ph.D., master, bachelor students to get into this manufacturing field instead of trying to move the supply chain, which is very costly and really non productive. That will slow down the innovation because– people trying to hold on their technology to their own and forsake the global collaboration.

Within the world of global collaboration there’s intense competition. Days after Intel announced spending $20 billion on two new fabs, TSMC announced it would spend $100 billion over three years on R&D, upgrades, and a new fab in Phoenix, Arizona, Intel’s backyard, where the Taiwanese company will produce the chips Apple needs but the Americans can’t make.

Mark Liu: That was a big investment.

But there’s a looming shadow over TSMC, which supplies chips for our cars, iPhones, and the supercomputer managing our nuclear stockpile: China’s President Xi Jinping, who has intensified his long-time threat to seize Taiwan.

China’s attempts to develop its own advanced chip industry have failed and so it’s been forced to import chips. But last year, Washington imposed restrictions on chipmakers from exporting certain semiconductors to china. Both Liu and Gelsinger fear the escalating trade war with China may backfire, and in Intel’s case: could hurt business.

Lesley Stahl: Are they your biggest customer?

Pat Gelsinger: China is one of our largest markets today. You know, over 25% of our revenue is to Chinese customers. We expect that this will remain an area of tension, and one that needs to be navigated carefully. Because if there’s any points that people can’t keep running their countries or running their businesses because of supply of one critical component like semiconductors, boy, that leads them to take very extreme postures on things because they have to.

The most extreme would be China invading Taiwan and in the process gaining control of TSMC. That could force the U.S. to defend Taiwan as we did Kuwait from the Iraqis 30 years ago. Then it was oil. Now it’s chips.

Lesley Stahl: The chip industry in Taiwan has been called the Silicon Shield.

Mark Liu: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: What does that mean?

Mark Liu: That means the world all needs Taiwan’s high-tech industry support. So they will not let the war happen in this region because it goes against interest of every country in the world.

Lesley Stahl: Do you think that in any way your industry is keeping Taiwan safe?

Mark Liu: I cannot comment on the safety. I mean, this is a changing world. Nobody want these things to happen. And I hope– I hope not too– either.

Despite the global push to ramp up production, the news is still grim. Some industry leaders and analysts expect the shortage to last deep into 2022, or even 2023.

Produced by Shachar Bar-On. Associate producer, Natalie Jimenez Peel. Broadcast associate, Wren Woodson. Edited by Warren Lustig.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has hardened his resolve against mask and vaccine mandates even as his state’s ICUs fill up. Joe Raedle/Getty

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has hardened his resolve against mask and vaccine mandates even as his state’s ICUs fill up. Joe Raedle/Getty ICUs around the country, like this one in California, have been filling up. But one Florida health system saw a 700 percent increase in the number of patients not breathing and flatlining throughout its COVID-19 units from June until Aug. 20. Apu Gomes/Getty

ICUs around the country, like this one in California, have been filling up. But one Florida health system saw a 700 percent increase in the number of patients not breathing and flatlining throughout its COVID-19 units from June until Aug. 20. Apu Gomes/Getty