DeSmog

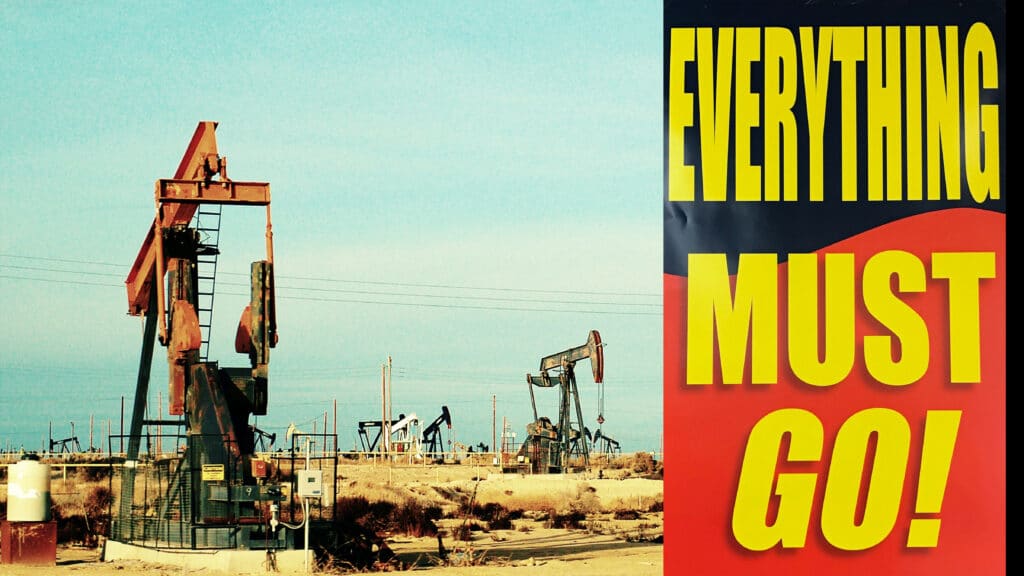

Struggling to Make a Profit, Fracking Investors are Searching for the Exit

The outlook is increasingly bleak for oil and gas companies. The beginning of this year has seen the highest number of companies announce bankruptcy during the first quarter in five years. Eight oil and gas companies announced they were filing for bankruptcy during the first quarter of 2021.

Meanwhile, earlier this month The Financial Times noted that of 500 privately owned oil and gas companies in the U.S., 400 are losing money and unlikely to ever pay back their large debts. According to the Financial Times, the remaining companies are focused on a “last gasp” effort to look profitable to potential buyers in order to “secure a profitable exit.”

If they can’t secure a “profitable exit” that will help them pay back their debts, the most likely outcome is bankruptcy.

As Adam Waterous, head of the private equity group Waterous Energy Fund, told the Financial Times: “This business is broken. The industry is going through a multiyear process of wringing capital out of the sector, not bringing new capital in.”

Investors appear to be done with the fracking industry as they realize that the only people making money are the Wall Street banks and shale company executives. With investors losing interest in the fracking industry — and banks no longer interested in loaning money to fracking companies — there is a lack of new money available to prop up the struggling fracking business model.

The U.S. fracking boom has all the echoes of the U.S. housing and mortgage financing boom of the early 2000s — and this is bad news for the industry. It’s a trend that’s been lurking for years.

As DeSmog reported in 2018, quoting from The Big Short, a book about the lead up to the 2008 financial crisis: “All these subprime lending companies were growing so rapidly, and using such goofy accounting, that they could mask the fact that they had no real earnings, just illusory, accounting-driven, ones. They had the essential feature of a Ponzi scheme: To maintain the fiction that they were profitable enterprises, they needed more and more capital to create more and more subprime loans.”

Like the housing bubble, the fracking bubble continued despite huge losses because companies were able to borrow more money to keep producing oil — that they then sold for a loss.

As Michael Lewis, author of The Big Short, pointed out, to keep a Ponzi scheme going requires a constant influx of new money because there are no profits. When the new money sources dry up — the scheme collapses.

Shale Investors Looking for Greater Fools

An April article by Bloomberg reports that the business strategy for private shale company owners is to now “escape” the industry altogether.

These investor plans to escape the fracking business, however, require willing buyers — or as they are known in this part of the business cycle, “greater fools.” This is the idea that you can make money from overpriced assets because there will always be someone else, the fool, willing to buy it at an even higher, inflated price. However, if there are no willing buyers, these investors will find themselves “holding the bag” — essentially stuck with a worthless investment.

The fracking company owners looking to escape by selling their companies know the financial numbers better than anyone — that explains their urgency to get out. As the Financial Times noted, most of these companies have debts far greater than any future potential income, making bankruptcy a near certainty in the future.

Bankruptcy has been a popular approach for many big shale companies — like Chesapeake Energy and Whiting Petroleum — but the ability to emerge from bankruptcy requires banks agreeing to loan more money to the company. If that option is unlikely, the company’s assets will be sold off, which is another unattractive option at this point with 400 oil and gas companies finances and assets making them “unsaleable.”

This cycle of foolish buying and selling resulted in the housing crisis when there was no one to keep buying, and it appears to be happening now with the fracking industry. The housing crisis was preceded by the creation of a whole industry of “house flippers” who borrowed money to buy houses to then resell for a profit. And the same has been seen with fracking.

As DeSmog wrote in 2018 about fracking giant Chesapeake Energy, its business model involved flipping land leases for oil and gas production, more than actually producing oil and gas. This approach — where fracking management teams are in the business of flipping companies for big gains more than extracting fossil fuels — was widespread with shale companies and highly lucrative for executives.

The business of flipping assets requires that there always be a well-funded “greater fool” willing to pay for them. As the money is drying up for the fracking industry the scheme is being revealed and — like the 400 U.S. shale companies the Financial Times described as “unsaleable” — those left holding the bag now are likely to lose big.

The early days of the fracking boom saw some tremendous success stories with flipping fracking assets with one of the biggest being the sale of XTO’s natural gas assets to Exxon in 2009 for $41 billion. Eventually even Exxon’s CEO Rex Tillerson admitted the company “probably paid too much”; that deal is now viewed as one of the worst deals in the history of oil and gas, resulting in Exxon writing off at least $20 billion of the investment last year. However, it was a great price for the owners of XTO.

More recently, in February, Equinor decided to cut its losses with the U.S. shale industry and sold its Bakken assets for $900 million. That’s far less than what Equinor paid when it first entered the Bakken in 2011 with an investment of $3.8 billion.

As these examples show, when everyone wants to escape a market, the usual outcome is very few do and those that do get out take huge losses.

The Return of Liar Loans

In January 2019, the Wall Street Journal reported that shale wells were not producing as much oil as the companies had promised investors. That article recounted a story from an oil industry conference where the idea that companies would properly estimate the potential future oil production brought a round of laughter from the conference attendees.

Why were fracking companies consistently overestimating the value of oil wells and reserves? “Because we own stock” was the answer from one conference attendee. This open admission that companies were lying about the value of their oil and gas assets to pump up their stock prices, combined with “lax corporate governance in the oil patch”, as a 2020 Reuters article describes, was a warning sign that the shale business was broken — and actively misleading investors.

One of the biggest problems behind the housing crisis were so-called liar loans. These were loans made to borrowers who lied about their income and assets to qualify as borrowers — even though the banks knew they were lying.

The same basic thing has happened with the fracking industry. In the oil business loans are based on a company’s reserves which refers to the amount of oil the company says they can produce from its assets. Banks lend against these assets in something known as reserve-based lending. What has happened in the fracking industry is that many companies may have been misleading about how much oil they can produce from their reserves.

Last year, DeSmog wrote about how reserve based lending for the fracking industry was a big problem. At the time, it was estimated that banks wrote off around $1 billion in reserve based loans for shale companies in 2019, exceeding their total losses for the past 30 years.

In December 2020, S&P Global wrote about the dim outlook for fracking companies and the banks that had loaned them money which included insights from Chris Holmgren, managing director for energy credit and risk management for Wells Fargo.

“The core reserve-based lending model began to break down. It became not successful in grasping the risks involved in shale development,” Holmgren said. “Lenders began to realize that they made decisions based on exaggerated potential.”

In the housing crisis they were liar loans. In the shale crisis they are “exaggerated potential” loans.

As expected, bankruptcies of shale companies are now on the rise in 2021 despite much higher oil prices. Just like many homeowners who borrowed money to buy houses they couldn’t afford based on their income, too many shale companies borrowed money to buy assets that will never produce enough income to pay back the money that was borrowed — even with higher oil prices.

In March, the CEO of Occidental Petroleum, Vicki Hollub, explained to attendees of leading oil industry conference CERAWeek that the economics of the shale industry were quite difficult when it came to producing profits.

“The profitability of shale,” she said, “is much more difficult than people ever realized.”

This fact is no longer a secret, which is why many fracking investors and banks are looking for a way to escape — but that escape seems unlikely.

Wells Fargo’s Holmgren described what could be the epitaph of the U.S. fracking revolution: “Banks are losing money and investors are stuck in investments they can’t get rid of.”

Transplanting melons in to high-residue beds on Full Belly Farm. (Photo courtesy of Full Belly Farm)

Transplanting melons in to high-residue beds on Full Belly Farm. (Photo courtesy of Full Belly Farm)

The first day of commercial fishing in 2019 on the Klamath River. (Photo courtesy of the Yurok Tribe)

The first day of commercial fishing in 2019 on the Klamath River. (Photo courtesy of the Yurok Tribe)