The New York Times

As Soon as Trump Leaves Office, He Faces Greater Risk of Prosecution

President Donald Trump lost more than an election last week. When he leaves the White House in January, he will also lose the constitutional protection from prosecution afforded to a sitting president.

After Jan. 20, Trump, who has refused to concede and is fighting to hold onto his office, will be more vulnerable than ever to a pending grand jury investigation by the Manhattan district attorney into the president’s family business and its practices, as well as his taxes.

The two-year inquiry, the only known active criminal investigation of Trump, has been stalled since last fall, when the president sued to block a subpoena for his tax returns and other records, a bitter dispute that for the second time is before the U.S. Supreme Court. A ruling is expected soon.

Trump has contended that the investigation by the district attorney, Cyrus R. Vance Jr., a Democrat, is a politically motivated fishing expedition. But if the Supreme Court rules that Vance is entitled to the records, and he uncovers possible crimes, Trump could face a reckoning with law enforcement — further inflaming political tensions and raising the startling specter of a criminal conviction, or even prison, for a former president.

“He’ll never have more protection from Vance than he has right now,” said Stephen I. Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas.

“Vance has been the wild card here,” Vladeck added. “And there is very little that even a new administration that wants to let bygones be bygones could do formally to stop him.”

A lawyer for the president, Jay Sekulow, declined to comment through a spokesman.

The district attorney’s investigation of a sitting president has taken on even greater significance because Trump’s past use of his presidential power — pardoning those close to him charged with federal crimes — suggests he will make liberal use of the pardon pen on behalf of associates, family members and possibly even himself, as he claimed he has the right to do.

But his pardon power does not extend to state crimes, like the possible violations under investigation by Vance’s office.

Vance’s inquiry could take on outsized importance if the incoming Biden administration, in seeking to unify the country and avoid the appearance of retaliation against Trump, shies away from new federal investigations.

Such a move would not bind the district attorney, an independent elected state official.

Vance’s lawyers acknowledged during the court fight over the subpoena that the Constitution bars them from prosecuting a president while in office, but the district attorney has said nothing about what might happen once Trump leaves the White House.

Danny Frost, a spokesman for Vance, declined to comment. It remains unclear whether the office will determine that crimes were committed and choose to prosecute Trump or anyone in his orbit.

Vance’s actions in the coming months are likely to put him under increasing political scrutiny. Trump will leave the White House amid calls for him to face criminal charges and a drumbeat of strident criticism from the left that he has evaded any legal consequences for his conduct over the years.

On the one hand, Vance could face pressure to forsake any charges to allow the country to move forward after a contentious presidential election. On the other, the district attorney was sharply criticized for his 2012 decision not to seek an indictment against Trump’s children, Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump Jr., after they were accused of misleading investors in a condo-hotel project. Vance has said that after a two-year investigation, his office could not prove a crime was committed.

Some legal experts said it would send the wrong message if Vance had evidence to justify charges but decided to walk away from a prosecution of Trump.

“That would put the president above the law,” said Anne Milgram, a former assistant district attorney in Manhattan and Democratic attorney general in New Jersey and a frequent critic of Trump.

And because Trump has repeatedly complained that the investigation was part of a broad partisan witch hunt, any decision to end it once the president left office could be seen as a tacit acknowledgment that such criticism was justified.

Few facts have been publicly disclosed about the course of the district attorney’s investigation or the people or potential crimes being examined because the inquiry is shielded by grand jury secrecy.

But during the legal battle over Vance’s subpoena, which sought eight years of Trump’s personal and corporate tax returns and other records from his accounting firm, prosecutors suggested in court papers that they were investigating a range of potential financial crimes. They include insurance fraud and criminal tax evasion, as well as grand larceny and scheming to defraud — which together are New York state&aposs equivalent of federal bank fraud charges.

And prosecutors argued in court that the documents they had demanded from the accounting firm, Mazars USA, represented “central evidence” for their investigation.

But they have provided little in the way of specifics beyond citing multiple news reports that detailed a range of potential criminal conduct by the president and his associates, including a series of 2018 New York Times articles that outlined possible tax crimes committed by Trump based on a detailed analysis of some of his tax return data obtained by the newspaper.

Trump, before and during his presidency, declined to publicly release his tax returns, breaking with 40 years of White House tradition, and he vigorously fought attempts by Congress and state lawmakers to obtain them.

The district attorney’s inquiry, which began in the summer of 2018, was first thought to focus on hush money payments made on behalf of Trump just days before the 2016 presidential election to an adult film star who had claimed she had an affair with him.

But the subpoena for Trump’s tax returns underscores an apparent greater focus on potential tax crimes, which tax experts, former prosecutors and defense lawyers agree can be among the toughest cases for the government to win at trial.

“The burden of proof is substantial,” said William J. Comiskey, a former longtime state prosecutor of white-collar and organized crime cases who later oversaw enforcement at New York’s Department of Taxation and Finance.

That, in large measure, is because prosecutors must prove that the defendant actually intended to evade taxes, Comiskey said.

And tax cases can be boring for jurors.

“They involve a complicated set of rules and numbers, and it’s hard for jurors — or anyone — to keep their focus through days and days of testimony,” said Amy Walsh, who handled tax cases as a federal prosecutor and later as a defense lawyer at a firm that specialized in tax matters.

The challenge in presenting such cases to a jury is compounded without a cooperating witness who can serve as a guide through complex financial strategies and records, or emails or other statements containing admissions, experts said.

“They need a smoking gun or they need someone to flip,” said Daniel J. Horwitz, who brought tax and complex fraud cases during more than eight years in the Manhattan district attorney’s office and is now a white-collar defense lawyer.

It is unknown whether Vance’s prosecutors have obtained the cooperation of any insiders for their investigation, but another consequence of Trump’s departure from office and loss of the power of the presidency could be that it would be easier for them to do so.

In addition to Vance’s inquiry, Trump also faces continuing scrutiny by New York state’s attorney general — who he has also claimed has targeted him out of partisan rancor.

In his lawsuit seeking to block the grand jury subpoena, Trump’s lawyers quoted 2018 campaign statements by Attorney General Letitia James, a Democrat, saying they were part of a “campaign to harass the president.”

They cited one statement, for example, in which she said Trump should worry because “we’re all closing in on him.”

Last year, James’ office opened a civil fraud investigation into Trump’s businesses. As recently as last month, Trump’s son Eric, after months of delays, was questioned under oath by the office’s lawyers.

Rebecca Roiphe, a former assistant district attorney in Manhattan who teaches legal ethics and criminal law at New York Law School, said James’ earlier statements made it appear there was some truth to the accusation that people who were investigating Trump were “at least capitalizing on that from a political perspective.”

The only way for Vance to avoid that perception, Roiphe said, was “to have a rock-solid case with overwhelming evidence, which will help convince the public that they’re holding the former president accountable for criminal acts.”

James, in response to criticism from Trump last year, tweeted that her office “will follow the facts of any case, wherever they lead.” She added: “Make no mistake: No one is above the law, not even the President.”

One thing seems likely: Defending against a white-collar investigation, even as a former president, will be challenging, stressful and disruptive for Trump, said Daniel R. Alonso, who was Vance’s top deputy from 2010 to 2014 and is now in private practice.

“There are subpoenas and seizures and documents all over the place, as well as constant meetings with lawyers,” Alonso said, adding, “It would certainly not be pleasant for him.”

The President’s supporters in Grand Rapids, Mich., ignored the chill at the final rally of his 2020 campaign. Peter van Agtmael—Magnum Photos for TIME

The President’s supporters in Grand Rapids, Mich., ignored the chill at the final rally of his 2020 campaign. Peter van Agtmael—Magnum Photos for TIME TIME illustration

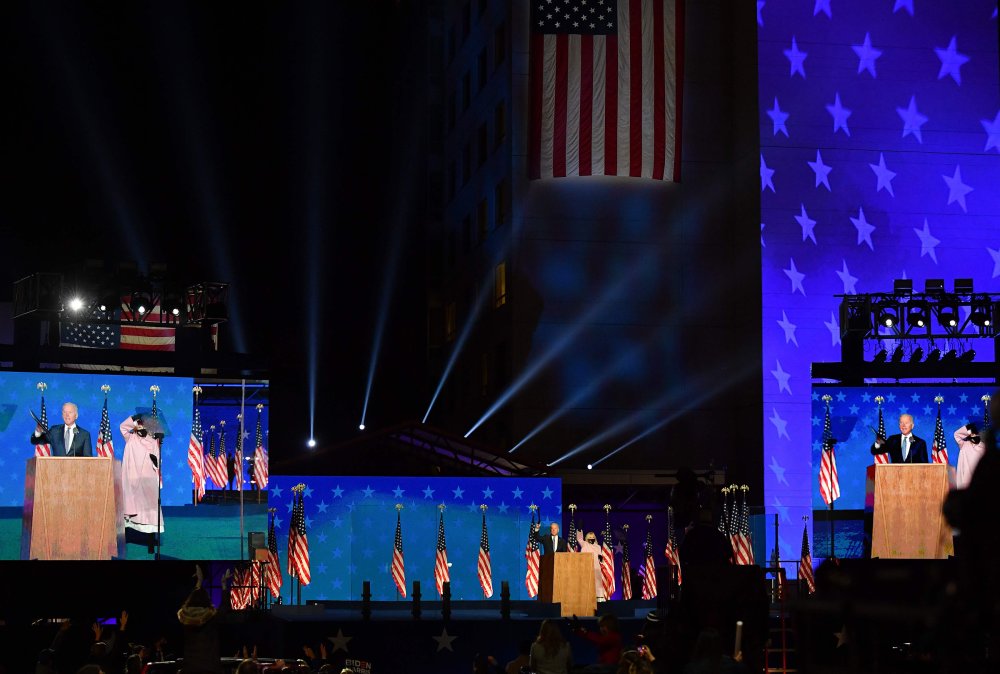

TIME illustration Steven Lewandowski views returns outside Chase Center in Wilmington, Del., on Nov. 3. Tony Luong for TIME

Steven Lewandowski views returns outside Chase Center in Wilmington, Del., on Nov. 3. Tony Luong for TIME Violetta Smith holds portrait balloons of Harris and Biden at an outdoor election-night event in Wilmington, Del. Tony Luong for TIME

Violetta Smith holds portrait balloons of Harris and Biden at an outdoor election-night event in Wilmington, Del. Tony Luong for TIME “It’s not my place or Donald Trump’s place to declare who’s won this election. That’s the decision of the American people.” — Joe Biden, at the Chase Center in Wilmington, Del., just after midnight on Nov. 4. Angela Weiss—AFP/Getty Images

“It’s not my place or Donald Trump’s place to declare who’s won this election. That’s the decision of the American people.” — Joe Biden, at the Chase Center in Wilmington, Del., just after midnight on Nov. 4. Angela Weiss—AFP/Getty Images “We’ll be going to the U.S. Supreme Court.” — Donald Trump, in the East Room of the White House early on the morning of Nov. 4. Peter van Agtmael—Magnum Photos for TIME

“We’ll be going to the U.S. Supreme Court.” — Donald Trump, in the East Room of the White House early on the morning of Nov. 4. Peter van Agtmael—Magnum Photos for TIME The different style of the campaigns—and of their supporters—was echoed in their Pennsylvania offices. Lorenzo Meloni—Magnum Photos for TIME

The different style of the campaigns—and of their supporters—was echoed in their Pennsylvania offices. Lorenzo Meloni—Magnum Photos for TIME David Lawrence, a Republican supporter, in Erie on Nov. 3. Lorenzo Meloni—Magnum Photos for TIME

David Lawrence, a Republican supporter, in Erie on Nov. 3. Lorenzo Meloni—Magnum Photos for TIME Reflecting the exhaustion on both sides of the aisle, a Trump fan rests on a table at an election-night party in Las Vegas. John Locher—AP

Reflecting the exhaustion on both sides of the aisle, a Trump fan rests on a table at an election-night party in Las Vegas. John Locher—AP