ABC News

‘It’s not their money’: Older Americans worried debt default means no Social Security

Peter Charalamboust – May 23, 2023

If the United States defaults on its financial obligations, millions of Americans might not be able to pay their bills as well.

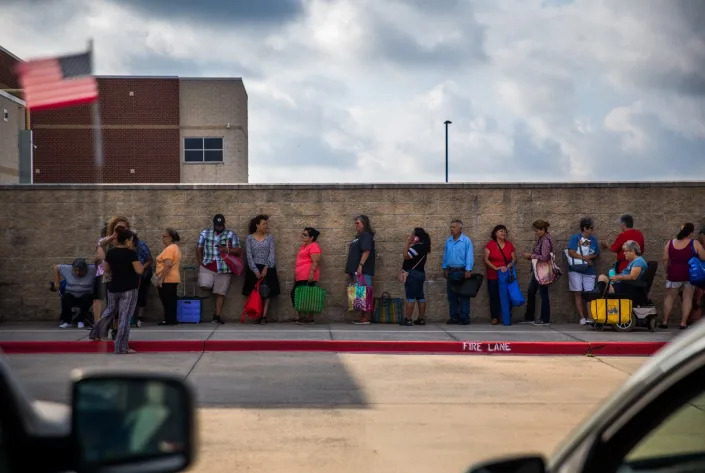

With Social Security and other government benefits at risk amid a political stalemate over the government’s debt ceiling, experts and older Americans told ABC News that the consequences of the impasse in Washington could be dire, including for older Americans who need the money to pay for basic needs such as food, housing or health care costs.

A quarter of Americans over age 65 rely on Social Security to provide at least 90% of their family income, according to the Social Security Administration.

Fred Gurner, 86, of New York, told ABC News that he uses his Social Security payment for his $800 rent. But now there is real risk that his payment might not come in time in June — when the Treasury Department says the government might not be able to send him the money he counts on.

“It’s very stressful, gives me a heart attack,” Gurner said about how the issue has become politicized.

How are Social Security payments affected by the debt ceiling?

Since 2001, the United States has spent more money than revenue it has taken in overall.

To cover the difference, the United States Treasury issues debt through securities, according to University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business professor Olivia Mitchell. Backed by the United States, those securities are happily bought by investors who see it as a safe guarantee they’ll get paid back with interest.

However, the United States and Denmark are the only two countries to limit the amount of debt the government can issue, known as a debt ceiling, Mitchell noted.

MORE: Ahead of meeting with Biden, McCarthy says debt, spending deal needed ‘this week’

Lawmakers can pass new laws that require government spending, but the debt ceiling will remain in place until lawmakers vote to increase it. That has happened 78 separate times in the United States since 1960.

If that debt ceiling does not increase by June 1, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has warned House Speaker Kevin McCarthy that the country will not be able to satisfy all of its financial obligations.

Beyond not being able to pay interest and principal on government securities — which economists broadly agree would rattle the stock market and possibly damage the U.S. credit rating — the Treasury would be unable to issue new debt to cover expenses like Social Security, according to Mitchell.

The government projects to spend roughly $100 billion on Social Security in the month of June, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center.

“It’s going to be pretty tight for people for a while, unless Congress and the president can get together on this problem,” Mitchell said.

When would Social Security payments become delayed?

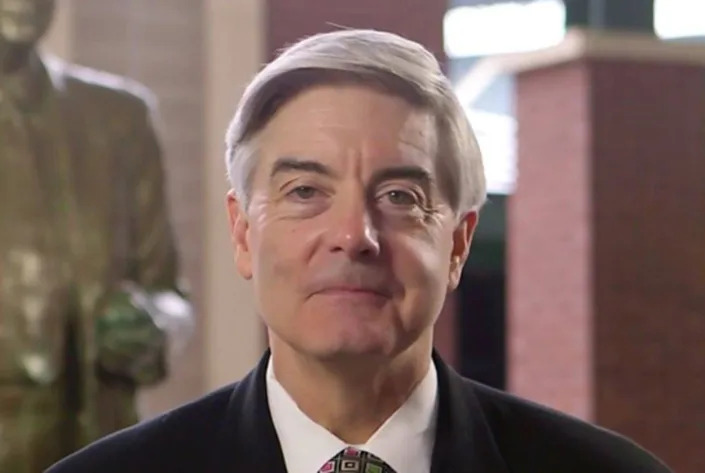

The Social Security Administration plans to send contributions to beneficiaries on four dates next month — June 2, 14, 21, and 28. Those checks would be the first ones at risk of being delayed, according to Max Richtman, President and CEO of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare.

“Millions and millions of Social Security beneficiaries are worried about having the income to pay their basic bills,” he noted.

Lynda Fisher, 80, told ABC News that her budget relies on her monthly Social Security check and that a delay would complicate her essential spending, frustrating the 80-year-old who has spent her life contributing to the system.

“I paid into Social Security, and I paid into Medicare,” she said. “And now they’re trying to take it away. It’s not their money, it’s my money that I paid into.”

Richtman is now actively encouraging older residents to save money in anticipation of a delayed Social Security payment, fearing negotiations will not yield a compromise in time to avoid default.

On NBC’s “Meet the Press” on Sunday, Yellen indicated that certain bills might be prioritized, including interest payments, Social Security and military contractor payments. However, Richtman expressed doubt that such a prioritization would be legally possible.

What does this mean for the future of Social Security?

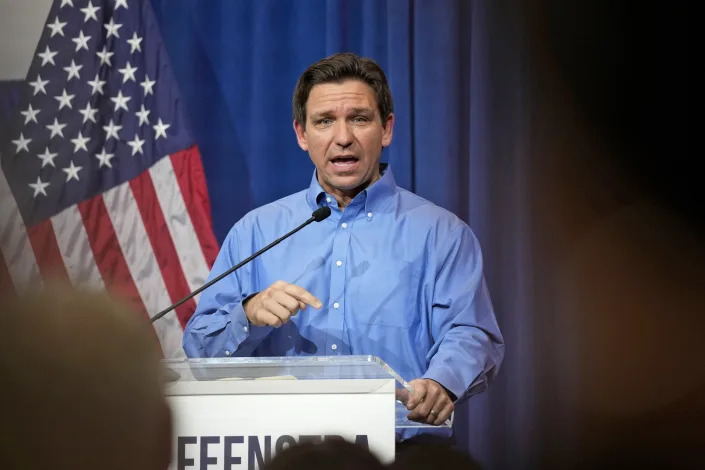

Some Republican lawmakers have framed the debt ceiling fight as necessary to slow government spending; however, some economists, including Mitchell, see this as a “manufactured crisis” that threatens essential services, retirement savings and the overall economy.

“Every time one of these crises occurs, it’s signaling to the rest of the world, and to American investors that U.S. Treasuries are not as safe as we thought,” Boston University economics professor Laurence Kotlikoff said.

MORE: Debt ceiling breach could cut millions of jobs. Here’s who would lose employment first

Kotlikoff expressed further concern that the Social Security system will have over $65.9 trillion in unfunded financial obligations over the indefinite horizon, based on the entity’s own report.

However, the debate over the debt ceiling appears unlikely to produce a meaningful solution to the broader Social Security shortfall, though, according to Kotlikoff, Mitchell and Richtman.

When will retirees receive their payments?

Mitchell and Richtman remained optimistic that Social Security recipients would eventually receive their checks once a deal is made, albeit with some delay.

“I’m pretty confident that payments would be fulfilled,” Richtman said. “That’s not much comfort to those people who will not be able to pay for their groceries, their utilities or their rent while they’re waiting to receive a back payment.”