Mother Jones

What Happened in Moscow: The Inside Story of How Trump’s Obsession With Putin Began.

His 2013 visit paved the way for a scandal that shook the world.

His 2013 visit paved the way for a scandal that shook the world.

By David Cone and Michael Isikoff March 8, 2028

This is the first of two excerpts adapted from Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump (Twelve Books), by Michael Isikoff, chief investigative correspondent for Yahoo News, and David Corn, Washington bureau chief of Mother Jones. The book will be released on March 13.

It was late in the afternoon of November 9, 2013, in Moscow, and Donald Trump was getting anxious.

This was his second day in the Russian capital, and the brash businessman and reality TV star was running through a whirlwind schedule to promote that evening’s extravaganza at Moscow’s Crocus City Hall: the Miss Universe pageant, in which women from 86 countries would be judged before a worldwide television audience estimated at 1 billion.

Trump had purchased the pageant 17 years earlier, partnering with NBC. It was one of his most prized properties, bringing in millions of dollars a year in revenue and, perhaps as important, burnishing his image as an iconic international playboy celebrity. While in the Russian capital, Trump was also scouting for new and grand business opportunities, having spent decades trying—but failing—to develop high-end projects in Moscow. Miss Universe staffers considered it an open secret that Trump’s true agenda in Moscow was not the show but his desire to do business there.

Yet to those around him that afternoon, Trump seemed gripped by one question: Where was Vladimir Putin?

From the moment five months earlier when Trump announced Miss Universe would be staged that year in Moscow, he had seemed obsessed with the idea of meeting the Russian president. “Do you think Putin will be going to The Miss Universe Pageant in November in Moscow—if so, will he become my new best friend?” Trump had tweeted in June.

Once in Moscow, Trump received a private message from the Kremlin, delivered by Aras Agalarov, an oligarch close to Putin and Trump’s partner in hosting the Miss Universe event there: “Mr. Putin would like to meet Mr. Trump.” That excited Trump. The American developer thought there was a strong chance the Russian leader would attend the pageant. But as his time in Russia wore on, Trump heard nothing else. He became uneasy.

“We all knew that the event was approved by Putin,” a Miss Universe official later said. “You can’t pull off something like this in Russia unless Putin says it’s okay.”

“Is Putin coming?” he kept asking.

With no word from the Kremlin, it was starting to look grim. Then Agalarov conveyed a new message. Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s right-hand man and press spokesman, would be calling any moment. Trump was relieved, especially after it was explained to him that few people were closer to Putin than Peskov. If anybody could facilitate a rendezvous with Putin, it was Peskov. “If you get a call from Peskov, it’s like you’re getting a call from Putin,” Rob Goldstone, a British-born publicist who had helped bring the beauty contest to Moscow, told him. But time was running out. The show would be starting soon, and following the broadcast Trump would be departing the city.

Finally, Agalarov’s cellphone rang. It was Peskov, and Agalarov handed the phone to an eager Trump.

Trump’s trip to Moscow for the Miss Universe contest was a pivotal moment. He had for years longed to develop a glittering Trump Tower in Moscow. With this visit, he would come near—so near—to striking that deal. He would be close to branding the Moscow skyline with his world-famous name and enhancing his own status as a sort of global oligarch.

RELATED: A Veteran Spy Has Given the FBI Information Alleging a Russian Operation to Cultivate Donald Trump

During his time in Russia, Trump would demonstrate his affinity for the nation’s authoritarian leader with flattering and fawning tweets and remarks that were part of a long stretch of comments suggesting an admiration for Putin. Trump’s curious statements about Putin—before, during, and after this Moscow jaunt—would later confound US intelligence officials, members of Congress, and Americans of various political inclinations, even Republican Party loyalists.

What could possibly explain Trump’s unwavering sympathy for the Russian strongman? His refusal to acknowledge Putin’s repressive tactics, his whitewashing of Putin’s abuses in Ukraine and Syria, his dismissal of the murders of Putin’s critics, his blind eye to Putin’s cyber-attacks and disinformation campaigns aimed at subverting Western democracies?

Trump’s brief trip to Moscow held clues to this mystery. His two days there would later become much discussed because of allegations that he engaged in weird sexual antics while in Russia—claims that were not confirmed. But this visit was significant because it revealed what motivated Trump the most: the opportunity to build more monuments to himself and to make more money. Trump realized he could attain none of his dreams in Moscow without forging a bond with the former KGB lieutenant colonel who was the president of Russia.

This trek to Russia was the birth of a bromance—or something darker—that would soon upend American politics and then scandalize Trump’s presidency. And it began in the most improbable way—as the brainstorm of a hustling music publicist trying to juice the career of a second-tier pop singer.

Trump’s Miss Universe landed in Moscow because of an odd couple: Rob Goldstone and Emin Agalarov.

Goldstone was a heavyset, gregarious bon vivant who liked to post photos on Facebook poking fun at himself for being unkempt and overweight. He once wrote a piece for the New York Times headlined, “The Tricks and Trials of Traveling While Fat.” He had been an Australian tabloid reporter and a publicist for Michael Jackson’s 1987 Bad tour. Now he co-managed a PR firm, and his top priority was serving the needs of an Azerbaijani pop singer of moderate talent named Emin Agalarov.

Emin—he went by his first name—was young, handsome, and rich. He yearned to be an international star. His father, Aras Agalarov, was a billionaire developer who had made it big in Russia, building commercial and residential complexes, and who also owned properties in the United States. After spending his early years in Russia, Emin grew up in Tenafly, New Jersey, obsessed with Elvis Presley. He imitated the King of Rock and Roll in dress, style, and voice. He later studied business at Marymount Manhattan College and subsequently pursued a double career, working in his father’s company and trying to make it as a singer. He married Leyla Aliyeva, the daughter of the president of Azerbaijan, whose regime faced repeated allegations of corruption. After moving to Baku, the country’s capital, Emin soon earned a nickname: “the Elvis of Azerbaijan.”

Emin cultivated the image of a rakish pop star, chronicling a hedonistic lifestyle on lnstagram by posting shots from beaches, nightclubs, and various hot spots. He brandished hats and T-shirts with randy sayings, such as “If You Had a Bad Day Let’s Get Naked.” But his music career was stalled. For help, he had turned to Goldstone.

During a January 2015 meeting, Trump told Emin, “Maybe next time, you’ll be performing at the White House.”

In early 2013, Goldstone was looking to get Emin more media exposure, especially in the United States. A friend offered a suggestion: Perhaps Emin could perform at a Miss Universe pageant. The event had a reputation for showcasing emerging talent. The 2008 contest had featured up-and-comer Lady Gaga. (Trump would later brag—with his usual hyperbole—that this appearance was Lady Gaga’s big break.) About the same time, Goldstone and Emin needed an attractive woman for a music video for Emin’s latest song—and they wanted the most beautiful woman they could find. It seemed obvious to them that they should reach out to Miss Universe.

This led to meetings with Paula Shugart, the president of the Miss Universe Organization, who reported directly to Trump. She agreed to make the reigning Miss Universe, Olivia Culpo, available for the music video. (Within the Miss Universe outfit, Culpo, who had previously been Miss USA, was widely considered a Trump favorite.) And over the course of several conversations with Shugart, Goldstone and Emin discussed where the next Miss Universe contest would be held. At one point, Emin proposed to Shugart that Miss Universe consider mounting its 2013 pageant in Azerbaijan. That didn’t fly with Shugart.

At a subsequent meeting, Emin revised the pitch. “Why don’t we have it in Moscow?” he suggested. Shugart was interested but hesitant. The pageant had looked at Moscow previously. It had not identified a suitable venue there, and it was fearful of running into too much red tape. “What if you had a partner who owns the biggest venue in Moscow?” Emin replied. “Between myself and my father, we can cut through the red tape.”

The venue Emin was referring to was Crocus City Hall, a grand 7,000-seat theater complex built by his father. Moreover, the influential Aras Agalarov could help smooth the way—and bypass the notorious bureaucratic morass that was a regular feature of doing business in Russia.

A native Azerbaijani, Aras Agalarov was known as “Putin’s Builder.” He had accumulated a billion-dollar-plus real estate fortune in part by catering, like Trump, to the super-wealthy. One of his projects was a Moscow housing community for oligarchs that boasted an artificial beach and waterfall. Agalarov had been tapped by Putin to build the massive infrastructure—conference halls, roadways, and housing—for the 2012 Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Vladivostok. He had completed the project in record time. That venture and others—the construction of soccer stadiums for the World Cup in Russia and the building of a superhighway around Moscow—had earned Agalarov Putin’s gratitude. Later in 2013, Putin would pin a medal on Agalarov’s lapel: “Order of Honor of the Russian Federation.”

When Shugart first mentioned to Trump the idea of partnering with a Russian billionaire tight with Putin to bring the Miss Universe contest to Moscow, the celebrity developer was intrigued. At last, here was an inside track to break into the Russian market. And Agalarov agreed to kick in a good chunk of the estimated $20 million pageant budget. Trump was all for it. A Putin-connected oligarch would be underwriting his endeavor.

But the deal had to include something for Emin. Trump’s Miss Universe company guaranteed that Emin would perform two musical numbers during the show. He would be showcased before a global television audience. He and Goldstone believed this could help him achieve his dream: cracking the American pop market.

Even before that, there would be a payoff for Emin. In May, Culpo showed up in Los Angeles for the one-day shoot. Emin was filmed strolling through a deserted nighttime town looking for his love—to the tune of his song “Amor”—and a sultry woman played by Culpo walked in and out of the beam of the flashlight he carried. A few weeks later, the video was done. Emin held a release party at a Moscow nightclub owned by his family. It was a lavish affair. Russian celebrities dropped by. Shugart and Culpo flew in to join the celebration.

In June 2013, Trump arrived in Las Vegas to preside over the Miss USA contest, which was owned by the Miss Universe company. Goldstone, Aras Agalarov, and Emin were in town for the event. Emin posted a photo of himself outside Trump’s hotel off the Vegas strip wearing a Trump T-shirt and boasting a hat exclaiming, “You’re Fired”—the tagline from Trump’s hit television show, The Apprentice. Trump had yet to meet the Agalarovs. But when they finally got together in the lobby of his hotel, he pointed at Aras Agalarov and exclaimed, “Look who came to me! This is the richest man in Russia!” (Agalarov was not the richest man in Russia.)

On the evening of June 15, the two Russians and their British publicist were planning a big dinner at CUT, a restaurant located at the Palazzo hotel and casino. Much to their surprise, they received a call from Keith Schiller, Trump’s longtime security chief and confidant, informing them that his boss wanted to join their party. Sure, they said, please come.

At the dinner for about 20 people in a private room, Emin sat between Trump and Goldstone. Aras Agalarov was across from Trump. Michael Cohen, Trump’s personal attorney who acted as the businessman’s consigliere, was on the other side of Goldstone. Also at the table was an unusual associate for Trump: Ike Kaveladze, the US-based vice president of Crocus International, an Agalarov company. In 2000, a Government Accountability Office report identified a business run by Kaveladze as responsible for opening more than 2,000 bank accounts at two US banks on behalf of Russian-based brokers. The accounts were used to move more than $1.4 billion from individuals in Russia and Eastern Europe around the globe in an operation the report suggested was “for the purpose of laundering money.” His main client at the time was Crocus International. (Kaveladze claimed the GAO probe was “another Russian witch-hunt in the United States.”)

Trump was charming and solicitous of his new partners. He asked Aras what kind of jet he owned. A Gulfstream 550, Aras answered. But the Russian billionaire quickly noted that he had a Gulfstream 650 on order. “If that was me,” Trump replied, “I would have said I was one of only 100 people in the world who have a Gulfstream 650 on order.” It was a small Trumpian lesson in self-promotion. And Trump, proud of himself, turned to Goldstone to emphasize his point: “There is nobody in the world who is a better self-promoter than Donald Trump.”

“When it comes to doing business in Russia, it’s very hard to find people in there you can trust,” Trump told Emin Agalarov. “We’re going to have a great relationship.”

After the dinner, part of the group headed to an after-party at a raunchy nightclub in the Palazzo mall called The Act. Shortly after midnight, the entourage arrived at the club. The group included Trump, Emin, Goldstone, Culpo, and Nana Meriwether, the outgoing Miss USA. Trump and Culpo were photographed in the lobby by a local paparazzi. The club’s management had heard that Trump might be there that night and had arranged to have plenty of Diet Coke on hand for the tea-totaling Trump. (The owners had also discussed whether they should prepare a special performance for the developer, perhaps a dominatrix who would tie him up onstage or a little-person transvestite Trump impersonator—and nixed the idea.)

The group was ushered to the owner’s box, where Emin had an unusual encounter. Alex Soros, the son of George Soros, the billionaire philanthropist who funded opposition to Putin, was there as Meriwether’s date. Emin started chatting with Soros and invited him to see him in Moscow. “You should know,” Soros replied, “I’m no fan of Mr. Putin.” And, he added, he was a big admirer of Mikhail Khodorkovsky—the oligarch turned Putin critic then serving time in a Siberian prison. Emin laughed it off.

The Act was no ordinary nightclub. Since March, it had been the target of undercover surveillance by the Nevada Gaming Control Board and investigators for the club’s landlord—the Palazzo, which was owned by GOP megadonor Sheldon Adelson—after complaints about its obscene performances. The club featured seminude women performing simulated sex acts of bestiality and grotesque sadomasochism—skits that a few months later would prompt a Nevada state judge to issue an injunction barring any more of its “lewd” and “offensive” performances. Among the club’s regular acts cited by the judge was one called “Hot for Teacher,” in which naked college girls simulate urinating on a professor. In another act, two women disrobe and then “one female stands over the other female and simulates urinating while the other female catches the urine in two wine glasses.” (The Act shut down after the judge’s ruling. There is no public record of which skits were performed the night Trump was present.)

As The Act’s scantily clad dancers gyrated in front of them late that night, Emin, Goldstone, Culpo, and the rest toasted Trump’s birthday. (He had turned 67 the day before.) Trump remained focused on Emin and their future partnership. “When it comes to doing business in Russia, it’s very hard to find people in there you can trust,” he told the young pop singer, according to Goldstone. “We’re going to have a great relationship.

The next night, toward the end of the Miss USA broadcast, Trump hit the stage to announce that the Miss Universe pageant would be held the coming November in Russia. In front of the audience, the Agalarovs and Trump signed the contract for the event. Trump declared, “This will be one of the biggest and most beautiful Miss Universe events ever.” On the red carpet earlier that evening, Trump had hailed Emin and Aras Agalarov: “These are the most powerful people in all of Russia, the richest men in Russia.”

Two days later, Trump expressed his desire on Twitter to become Putin’s “new best friend.” Emin quickly responded with his own tweet: “Mr. @realDonaldTrump anyone you meet becomes your best friend—so I’m sure Mr. Putin will not be an exception in Moscow.”

The Moscow event held great potential for Trump to score in Russia. Now he was partnering with a Russian billionaire connected to other oligarchs and favored by Putin. (Trump already had a controversial venture underway in Baku, where he was developing a hotel with the son of the transportation minister of the corrupt regime. This project would soon founder.) “For Trump, this Miss Universe event was all about expanding the Trump Organization brand and getting his names on buildings,” a Miss Universe associate recalled.

And anyone who wanted to do big deals in Russia—especially an American—could only do so if Putin was keen on it. “We all knew that the event was approved by Putin,” a Miss Universe official later said. “You can’t pull off something like this in Russia unless Putin says it’s okay.” Trump would only be making money in Russia because Putin was permitting him to do so.

RELATED: How the GOP Pulled Me Into Its War on the FBI

Immediately, the contest was slammed by controversy. A few days before the announcement in Las Vegas, the Russian Duma had passed a law that made it illegal to expose children to information about homosexuality. The new anti-gay measure was the latest move by Putin to appeal to the conservative Orthodox Church and ultranationalist forces. It came amid a disturbing rise in anti-gay violence throughout Russia. In the southern city of Volgograd a few weeks earlier, a gay man’s naked body was found in a courtyard, his skull smashed, his genitals scarred by beer bottles. The atmosphere was “ugly and brutal,” a US diplomat who then served in Moscow later said. “There would be these hooligans who would go after gay people in bars and beat them up. There was a pretty vicious campaign against the LGBT community.”

Human rights and gay rights advocates in Russia and around the world denounced the new law. Vodka boycotts were launched. There was a push to relocate the Winter Olympics, scheduled to be held the following year in Sochi, Russia. In the United States, the Human Rights Campaign called on Trump and the Miss Universe Organization to move the event out of Russia, noting that under the new law a contestant could be prosecuted if she were to voice support for gay rights.

The uproar over the Russian anti-gay act confronted Trump with a dilemma—how to distance himself from the law without jeopardizing his big Russia play. The Miss Universe Organization issued a statement asserting that it “believes in equality for all individuals.” That didn’t stop the protests. Bravo talk-show host Andy Cohen and entertainment reporter Giuliana Rancic, who had previously co-hosted the pageant, quit the show. Miss Universe officials scrambled and found replacements: Thomas Roberts, an openly gay MSNBC anchor, and former Spice Girl Mel B.

Roberts explained his decision in an op-ed on MSNBC.com: “Boycotting and vilifying from the outside is too easy. Rather, I choose to offer my support of the LGBT community in Russia by going to Moscow and hosting this event as a journalist, an anchor, and a man who happens to be gay. Let people see I am no different than anyone else.

This was a godsend for Trump. He granted Roberts an interview on MSNBC. “I think you’re going to do fantastically,” he told Roberts, “and I love the fact that you feel the same about the whole situation as me.” Inevitably, the conversation turned toward Putin and whether he would appear at the pageant. “I know for a fact that he wants very much to come,” Trump said, “but we’ll have to see. We haven’t heard yet, but we have invited him.”

Though US relations with Moscow were at this point deteriorating, Trump was touting Putin as a wily and strong leader. In September, Putin published an op-ed in the New York Times that opposed a possible US military strike against the government of Bashar al-Assad in Syria (in retaliation for its use of chemical weapons) and that denounced President Barack Obama for referring to American exceptionalism. The next day, Trump on Fox News commended Putin’s move. “It really makes him look like a great leader,” he said.

The following month, Trump appeared on David Letterman’s late-night show. The host asked if Trump had ever done any deals with the Russians. “I’ve done a lot of business with the Russians,” Trump replied, adding, “They’re smart and they’re tough.” Letterman inquired if Trump had ever met Putin. “He’s a tough guy,” Trump said. “I met him once.” In fact, there was no record he ever had.

Trump landed in Moscow on November 8, having flown there with casino owner Phil Ruffin on Ruffin’s private jet. (Ruffin, a long-time Trump friend, was married to a former Miss Ukraine who had competed in the 2004 Miss Universe contest.) Trump headed to the Ritz-Carlton, where he was booked into the presidential suite that Obama had stayed in when he was in Moscow four years earlier.

There was a brief meeting with Miss Universe executives and the Agalarovs. Schiller would later tell congressional investigators that a Russian approached Trump’s party with an offer: He wanted to send five women to Trump’s hotel room that night. Was this traditional Russian courtesy—or an overture by Russian intelligence to collect kompromat (compromising material) on the prominent visitor? Schiller said he didn’t take the offer seriously and told the Russian, “We don’t do that type of stuff.”

Trump was soon whisked to a gala lunch at one of the two Moscow branches of Nobu, the famous sushi restaurant. (Nobu Matsuhisa, its founder, was one of the celebrity judges for the Miss Universe telecast. Agalarov was one of the co-owners of the restaurant; another co-investor was actor Robert De Niro.) An assortment of Russian businessmen was there, including Herman Gref, the chief executive of Sberbank, a Russian state-owned bank and one of the co-sponsors of the Miss Universe pageant.

“[Trump] often thought a woman was too ethnic or too dark-skinned. He had a particular type of woman he thought was a winner. Others were too ethnic. He liked a type. There was Olivia Culpo, Dayanara Torres [the 1993 winner], and, no surprise, East European women.”

Trump was treated with much reverence. He gave a brief welcoming talk. “Ask me a question,” he told the crowd. The first query was about the European debt crisis and the impact that the financial woes of Greece would have on it. “Interesting,” Trump replied. “Have any of you ever seen The Apprentice?” Trump spoke at length about his hit television show, repeatedly noting what a tremendous success it was. He said not a word about Greece or debt. When he was done with his remarks, he thanked them all for coming and received a standing ovation. (Later, Aras Agalarov, reminiscing about this lunch, would note, “If [Trump] does not know the subject, he will talk about a subject he knows.”)

Gref, a close Putin adviser, was pleased with his face time with Trump. “There was a good feeling from the meeting,” he later said. “He’s a sensible person…[with] a good attitude toward Russia.”

Trump next went to the theater in Crocus City Hall. It was the day before the show. This was Trump’s chance to review the contestants and exercise an option he always retained under the rules of his pageants: to overrule the selection of judges and pick the contestants he wanted among the finalists. In short, no woman was a finalist until Trump said so.

At each pageant, Miss Universe staffers would set up a special room for Trump backstage. It had to conform to his precise requirements. He needed his favorite snacks: Nutter Butters and white Tic Tacs. And Diet Coke. There could be no distracting pictures on the wall. The room had to be immaculate. He required unscented soap and hand towels—rolled, not folded.

In this room would be videos of the finalists who had been selected days earlier in a preliminary competition and the other contestants, particularly footage of the women in gowns and swim suits. Here, a day or two before the final telecast, Trump would review the judges’ decisions.

Frequently, Trump would toss out finalists and replace them with others he preferred. “If there were too many women of color, he would make changes,” a Miss Universe staffer later noted. Another Miss Universe staffer recalled, “He often thought a woman was too ethnic or too dark-skinned. He had a particular type of woman he thought was a winner. Others were too ethnic. He liked a type. There was Olivia Culpo, Dayanara Torres [the 1993 winner], and, no surprise, East European women.” On occasion, according to this staffer, Trump would reject a woman “who had snubbed his advances.”

Once in a while, Shugart would politely challenge Trump’s choices. Sometimes she would win the argument, sometimes not. “If he didn’t like a woman because she looked too ethnic, you could sometimes persuade him by telling him she was a princess and married to a football player,” a staffer later explained.

That night, Aras Agalarov hosted a party at Crocus City Hall to celebrate his 58th birthday. Various VIPs were invited. Trump by now was exhausted. He spent much of the time sitting with Shugart and Schiller. At one point, Goldstone approached him with a request from Emin. The pop star was filming a new music video. Could Trump the next day shoot a scene that would be based on The Apprentice? Trump agreed, but it had to be early— between 7:45 and 8:10 in the morning. Sure, Goldstone said. Twenty-five minutes of Trump would have to do.

At about 1:30 a.m., Trump left the party and headed to the Ritz-Carlton hotel a few blocks from the Kremlin. This would be his only night in Moscow. According to Schiller, on the way to the hotel, he told Trump about the earlier offer of women, and he and Trump laughed about it. In Schiller’s account, after Trump was in his room, he stood guard outside for a while and then left.

(But Schiller by another account was accustomed to being a go-between for Trump. In a 2011 interview with In Touch Weekly magazine that was not published until early 2018, Stormy Daniels, a porn star who claimed she had an 11-month-long affair with Trump, identified Schiller as the Trump aide who facilitated her secret liaisons with Trump. “That’s how I got in touch with him,” Daniels said. “I never had Donald’s cellphone number. I always used Keith’s. I went up to the room and he said, “Oh yeah, he’s waiting for you inside.’”)

The morning of November 9, Trump showed up for Emin’s shoot. He was needed for the final scene. The video would open with a boardroom meeting with Emin and others reviewing Miss Universe contestants. Emin would doze off and dream of being with the various contestants. Enter Trump for the climax—Emin wakes up with Trump shouting at him: “What’s wrong with you, Emin? Emin, let’s get with it. You’re always late. You’re just another pretty face. I’m really tired of you. You’re fired!” Trump’s bit would only last 15 seconds. Yet soon Emin would release a video that he could promote as featuring the world-famous Trump.

The rest of the day was as hectic as the first: a press conference with 300 Russian reporters and more interviews, including one with Roberts in which Trump was pressed again about Putin.

Do you have a relationship with Putin and any sway with the Russian leader? Roberts asked him. Trump was unequivocal: “I do have a relationship.” He paused. “I can tell you that he’s very interested in what we’re doing here today. He’s probably very interested in what you and I are saying today. And I’m sure he’s going to be seeing it in some form.”

Trump could barely contain his praise for Russia’s president: “Look, he’s done a very brilliant job in terms of what he represents and who he’s representing. If you look at what he’s done with Syria, if you look at so many of the different things, he has really eaten our president’s lunch. Let’s not kid ourselves. He’s done an amazing job…He’s put himself at the forefront of the world as a leader in a short period of time.”

But Trump’s comments about a “relationship” with Putin were, at this point, wishful thinking. The word had spread through the Miss Universe staff that Trump fiercely craved Putin’s attendance at the pageant. In preparation for Putin’s possible appearance, Thomas Roberts and Mel B were taught several words in Russian to welcome the Russian president: “hello,” “thank you,” and so on. With her cockney accent, Mel B had trouble pronouncing the Russian words. She was told she had to get this right because Putin might come.

By late afternoon, Trump’s anxiety was palpable. There had been no word. He kept asking if anybody had heard from Putin. Then Agalarov’s phone rang. “Mr. Peskov would like to speak to Mr. Trump,” Agalarov said.

Trump suggested to an associate that after the telecast they could spread the word that Putin had dropped by. “No one will know for sure if he came or not.”

Trump and Peskov spoke for a few minutes. Afterward, Trump recounted the conversation to Goldstone. Peskov, he said, was apologetic. Putin very much wanted to meet Trump. But there was a problem nobody had anticipated: a Moscow traffic jam. King Willem-Alexander and Queen Maxima of the Netherlands were in town, and Putin was obligated to meet them at the Kremlin. But the royal couple had gotten stuck in traffic and was late, making it impossible for the Russian president to find time for Trump. Nor would he be able to attend the Miss Universe pageant that evening.

Putin wanted to make amends, though. Peskov conveyed an invitation for Trump to attend the upcoming Olympics, where perhaps he and Putin could then meet. He also told Trump that Putin would be sending a high-level emissary to the evening’s event—Vladimir Kozhin, a senior Putin aide. And, Peskov told Trump, Putin had a gift for him.

It was a crushing disappointment for Trump. But he quickly thought of how to spin it, suggesting to an associate that after the telecast they could spread the word that Putin had dropped by. “No one will know for sure if he came or not,” he said.

One reason Trump’s hoped-for meeting with the Russian president never materialized was his attention to another project. Trump was originally scheduled to spend two nights in Moscow—which would have yielded a wider window for a get-together with Putin. But Trump had decided to attend the celebration of evangelist Billy Graham’s 95th birthday on November 7 at the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, North Carolina. In Russia, Trump told Goldstone that it had been necessary for him to show up at the Graham event: “There is something I’m planning down the road, and it’s really important.”

Goldstone knew exactly what Trump was talking about: a run for the White House. Franklin Graham, the evangelist’s son, was an influential figure among religious conservatives. When Trump two years earlier was championing birtherism—the baseless conspiracy theory that Barack Obama had been born in Kenya and was ineligible to be president—Graham joined the birther bandwagon, raising questions about the president’s birth certificate. Appearing at this event and currying favor with Franklin Graham was a mandatory stop for Trump, if he was serious about seeking the Republican presidential nomination. And it paid off: Trump and his wife Melania were seated at the VIP table along with Rupert Murdoch and Sarah Palin. Franklin Graham later said that Trump was among those who “gave their hearts to Christ” that night.

Before the Miss Universe broadcast, there was the obligatory red-carpet event. Camera crews from around the world recorded the strutting celebrities. A triumphant-looking Trump posed with Aras and Emin Agalarov for the paparazzi. Trump dodged a question about whether Emin had been booked to perform based on merit.

“Russia has just been an amazing place,” Trump exclaimed. “You see what’s happening here. It’s incredible.” Behind him was a banner featuring the logos of the Trump Organization, Miss Universe, Sberbank, Mercedes, and NBC. The NBC peacock was in black and white, without its usual rainbow of colors. Officials at Agalarov’s company had ordered Miss Universe staffers to eschew the rainbow, fearing it would be seen as a gay pride message.

Edita Shaumyan caught Trump’s eye. “You’re beautiful,” Trump told her. “Wow, your eyes, your eyes.” According to Shaumyan, “He said, ‘Let’s go to America. Come with me to America.’”

Thomas Roberts walked the red carpet with his husband. He wore a bright pink tuxedo jacket—something he would never do back home in New York. He was sending his own message. In interviews, he explicitly denounced Putin’s anti-gay laws.

Other celebs and local notables strolled past the entertainment reporters. The group included Kozhin and a curious guest: Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov, a.k.a. “the Little Taiwanese,” one of Russia’s most prominent suspected mobsters and a fugitive from US justice. Tokhtakhounov had an odd link to Trump’s signature property: Seven months earlier, he had been indicted in the United States for protecting a high-stakes illegal gambling operation run out of Trump Tower. Additional Trump guests included Chuck LaBella, an NBC executive who worked on Trump’s Celebrity Apprentice, and Bob Van Ronkel, an American expatriate who ran a business specializing in bringing Hollywood celebrities to Russian events. (Van Ronkel once had tried to produce an American television show extolling the KGB and its heroic exploits.)

The show went off well. Trump sat in the front row next to Agalarov. Emin performed two of his Euro-pop numbers. Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, one of the judges, pumped out his classic hit “Dream On.” For the finale, Culpo crowned Miss Venezuela the new Miss Universe. There was no mention during the broadcast of the controversy over the anti-gay law.

After the event, there was a rowdy after-party with lots of vodka and loud music. A 26-year-old aspiring actress, Edita Shaumyan, made her way into the VIP section, entering the roped-off area the same time as a famous Russian rap singer named Timati. Shaumyan caught Trump’s eye. He approached her, gestured to Timati, and asked, “Wait, is this your boyfriend? You’re not free?” She said no. “You’re beautiful,” Trump told her. “Wow, your eyes, your eyes.” According to Shaumyan, “He said, ‘Let’s go to America. Come with me to America.’ And I said, ‘No, no, no. I’m an Armenian. We’re very strict. You need to meet my mother first.’” When other women approached, trying to get photographs with Trump, he took hold of Shaumyan’s arm and said, “Don’t go. Stay. Stay.” Shaumyan took selfies with him. (She later produced five photos and a video of her with Trump that night.) But nothing further happened. Trump later had somebody give Shaumyan his business card with his phone number on it. She never called.

From the party, Trump headed to the airport. He was going straight home on another Ruffin jet. The next day, he called Roberts. He told him he was pleased with the show and that it had been a smash, with great ratings. That was not accurate—at least not in the United States. The telecast drew 3.8 million viewers, much less than the 6.1 million who had watched it the previous year.

In the following days, various media outlets in Russia and the United States reported that Trump had used his visit to Moscow to launch a major project in the Russian capital. “US ‘Miss Universe’ Billionaire Plans Russian Trump Tower,” declared the headline on RT, the Russian government-owned TV channel and website. The Moscow Times proclaimed, “Donald Trump Planning Skyscraper in Moscow.” Trump’s partners in the Trump SoHo project he had developed in New York City—Alex Sapir and Rotem Rosen—had come to Moscow for the event and met with Agalarov and Trump to discuss the possibilities.

Agalarov’s daughter showed up at the Miss Universe office in New York City bearing a gift for Trump from Putin…Inside was a sealed letter from the Russian autocrat. What the letter said has never been revealed.

It seemed things were moving fast. The state-owned Sberbank announced it had struck a “strategic cooperation agreement” with the Crocus Group to finance about 70 percent of a project that would include a tower bearing the Trump name. If the deal went ahead, Trump would officially be doing business in Moscow with the Russian government.

“The Russian market is attracted to me,” Trump told Real Estate Weekly. “I have a great relationship with many Russians.” He added, with his customary exaggeration, “Almost all of the oligarchs” had been at the Miss Universe event.

Back in the United States, Trump tweeted out the good news: “I just got back from Russia—learned lots & lots. Moscow is a very interesting and amazing place!” The next day he tweeted at Aras Agalarov, “I had a great weekend with you and your family. You have done a FANTASTIC job. TRUMP TOWER-MOSCOW is next. EMIN was WOW!

The project moved further along than publicly known. A letter of intent to build the new Trump Tower was signed by the Trump Organization and Agalarov’s company. Donald Trump Jr. was placed in charge of the project.

Trump was finally on his way in Russia. And shortly after the Miss Universe event, Agalarov’s daughter showed up at the Miss Universe office in New York City bearing a gift for Trump from Putin. It was a black lacquered box. Inside was a sealed letter from the Russian autocrat. What the letter said has never been revealed.

In February 2014, Ivanka Trump flew to Moscow to scout potential sites for the Trump Tower project with Emin Agalarov. “We thought that building a Trump Tower next to an Agalarov tower—having the two big names—could be a really cool project to execute,” Emin later said.

But international events would quickly intervene. Weeks after Ivanka’s visit, the Obama administration and the European Union imposed tough sanctions on Russia in response to Putin’s annexation of Crimea and his military intervention in Ukraine. It would be a kick to Russia’s faltering economy, already struggling because of the plummeting price of oil. And one round of sanctions imposed by the European Union targeted Russian banks in which the Russia government held a majority interest—that included Sberbank, which had agreed to finance the Trump deal. Its access to capital was now hindered.

Rob Goldstone suspected the demise of Trump’s project with the Agalarovs influenced Trump’s view of sanctions: “They had interrupted a business deal that Trump was keenly interested in.”

In this environment, the plans for the Trump Tower in Moscow crumbled. According to the Trump Organization, Ivanka Trump, after touring Moscow with Emin, killed the deal for business reasons. But Rob Goldstone suspected the demise of Trump’s project with the Agalarovs influenced Trump’s view of sanctions: “They had interrupted a business deal that Trump was keenly interested in.”

That deal was dead. But Trump’s involvement with Russia and Putin was not done. He still had a close bond with an influential oligarch, Aras Agalarov, who was wired into the Kremlin. And he stayed in touch with his Miss Universe pals, Emin and Goldstone. In January 2015, nearly a year after Putin’s invasion in Ukraine, Trump had Emin and Goldstone as guests to his office in Trump Tower—a meeting that was never publicly revealed during the investigations that followed the 2016 election. As Goldstone recalled it, they found Trump listening to the blaring sounds of a “hideous” rap video about Trump. The lyrics were ridiculing Trump, and Goldstone asked, “Have you listened to the words?” Trump replied, “Who cares about the words? It has 90 million hits on YouTube.” While they chatted, Trump was encouraging to Emin, who had performed at the Miss Universe contest in 2013: “Maybe next time, you’ll be performing at the White House.”

Seventeen months later, in June 2016, Goldstone would return to Trump Tower—this time escorting a Russian-led delegation dispatched by the Agalarovs, offering potentially derogatory information on Hillary Clinton, courtesy of the Kremlin, to the top officials of Trump’s presidential campaign.

Image credit: Pavel Golovkin/AP; Olivier Douliery/CNP/ZUMA; Mikhail Klimentyev/Sputnik/AP

FACT:

Mother Jones was founded as a nonprofit in 1976 because we knew corporations and the wealthy wouldn’t fund the type of hard-hitting journalism we set out to do.

Today, reader support makes up about two-thirds of our budget, allows us to dig deep on stories that matter, and lets us keep our reporting free for everyone. If you value what you get from Mother Jones, please join us with a tax-deductible donation so we can keep on doing the type of journalism that 2018 demands. DONATE NOW

David Corn is Mother Jones‘ Washington bureau chief. For more of his stories, click here

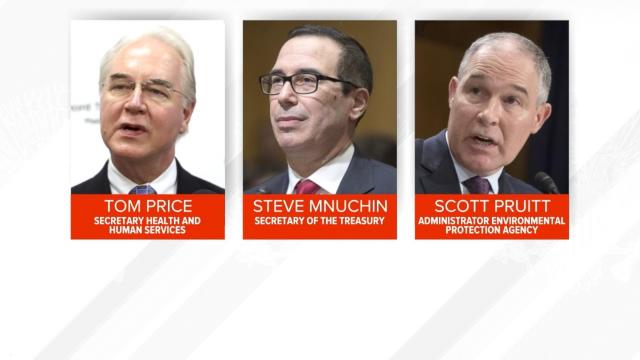

Interior Spokeswoman Heather Swift said in a statement that Secretary Ryan Zinke was not aware of the order before the Associated Press report on Thursday and agrees that it is too expensive. The AP first reported the story.

Interior Spokeswoman Heather Swift said in a statement that Secretary Ryan Zinke was not aware of the order before the Associated Press report on Thursday and agrees that it is too expensive. The AP first reported the story. Zinke has been under scrutiny for his spending on travel, which has been an issue with

Zinke has been under scrutiny for his spending on travel, which has been an issue with  From left, Russian President Vladimir Putin, presidential candidates Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, CIA Director John Brennan, President Barack Obama and national security adviser Susan Rice. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP (7), Getty Images)

From left, Russian President Vladimir Putin, presidential candidates Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, CIA Director John Brennan, President Barack Obama and national security adviser Susan Rice. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP (7), Getty Images)

Photo illustration: Yahoo News

Photo illustration: Yahoo News Russian President Vladimir Putin, Aras Agalarov, Rob Goldstone, Emin Agalarov, Donald Trump and Olivia Culpo. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images, Jeff Bottari/AP, Adriel Reboh/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images, Victor Boyko/Getty Images, Maxim Shemetov/Reuters)

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Aras Agalarov, Rob Goldstone, Emin Agalarov, Donald Trump and Olivia Culpo. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images, Jeff Bottari/AP, Adriel Reboh/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images, Victor Boyko/Getty Images, Maxim Shemetov/Reuters) His 2013 visit paved the way for a scandal that shook the world.

His 2013 visit paved the way for a scandal that shook the world.

Yahoo News photo illustration; photos: AP, Getty

Yahoo News photo illustration; photos: AP, Getty