AZ Central – The Arizona Republic

At Lake Powell, a ‘front-row seat’ to a drying Colorado River and an uncertain future

Brandon Loomis, Arizona Republic – December 13, 2022

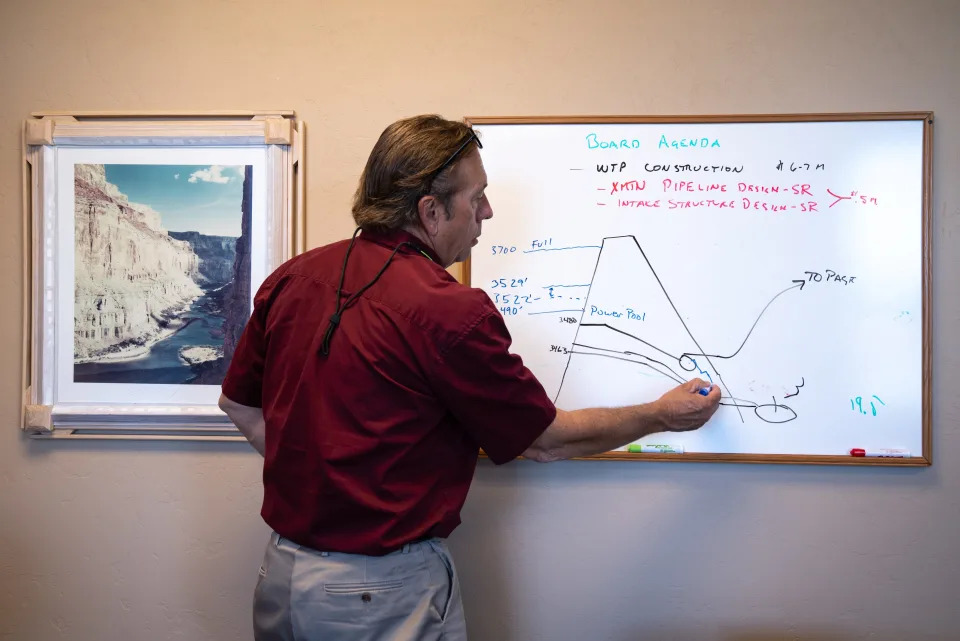

PAGE — At his office whiteboard on this dam town’s desert edge, the water utility manager recited the federal government’s latest measures of the colossal reservoir that lay 4 miles down the road, then scrawled an ominous sketch showing how far it has shrunk.

In his stylized drawing of Lake Powell, the surfacelapped just above where he marked his town’s drinking water pipe, bringing the Colorado River drought crisis uncomfortably close to home.

Against a diagram of Glen Canyon Dam’s concrete arch, Bryan Hill used blue marker to ink progressively shallower water lines from 22 years of Southwestern drought and overuse: 3,700 feet above sea level when full. Just 3,529 feet now.

He was updating a presentation he had created to reassure a worried City Council that it was merely time to act, not to panic. That day’s line fell just 39 feet above a black one Hill had drawn to indicate the dam’s hydropower intakes, the point at which the last of 1,320-megawatts flickers off.

As personal as the threat feels to Hill and his neighbors, his charts depicted a troubling reality for millions of other water users. If the lake keeps dropping below those generator intakes, dam managers will have difficulty pushing enough water downstream to keep Lake Mead from tanking and to satisfy the Southwest’s legal rights to water.

Lake Mead’s own decline threatens to upend a vast irrigated agricultural empire in Southern California and southwestern Arizona, and to restrict or eventually cut off a significant source of hydroelectricity and household water for the urban Southwest.

Powell once seemed Mead’s failsafe backup, a reservoir that, in a wet string of years, could accumulate far more than what the river delivers in a single year. During dry spells, it could pour its excess through Grand Canyon and into Mead, supplying users downstream.

Now the excess was gone. Hill’s drawing showed a reservoir on the brink after two decades of aridification, holding less water than it is supposed to send downstream in the coming year. Further declines could lend momentum to a long-simmering clamor for moving most or all of Powell’s stored water down to Mead.

If the snows that melt to replenish the reservoir are lower than expected this winter, the dam’s managers warn, it’s possible that water will dip below Glen Canyon Dam’s hydropower intakes by the end of 2023.

Page and a neighboring Navajo Nation community, Lechee, get their water from those same intakes, constructed at an elevation that government dam builders in the 1950s and ‘60s expected to remain forever inundated.

It was late May when Hill stood at his whiteboard, and snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains had started coursing down the Colorado to provide the storage pool a temporary, seasonal lift from its most recent record low. Still, the intakes sat just 39 feet below a surface that already had fallen 148 feet since the same date in 2000. After trees, plants and parched soil took their share, this spring’s runoff was shaping up poorly again. One more dry winter, Hill predicted, and “shit gets real.”

Page won’t go dry, for now. Its 7,500 residents and another 3,000 in Lechee will draw water from an emergency pipe link that federal officials are designing and connecting to tap deeper tunnels that allow managers to bypass the hydro powerplant when necessary or desired, such as for environmental flows downstream in Grand Canyon.

Even those tunnels are at risk of drying in coming years. Soon, the region’s accelerating aridification will force Page, like the vast irrigated farms and growing metropolises throughout the Southwest, to dig deeper for a solution.

Already, southern Nevada has spent $817 million to build a deeper tunnel under Lake Mead — a new “straw” into the reservoir — to keep water flowing to Las Vegas.

There are 40 million people who rely on the Colorado River water stored here, and millions more who eat the vegetables, beef and winter greens that it grows. They all face hazards on the desiccated horizon. For the few thousand who live on a red-rock bluff by the plunging reservoir, it’s in full view.

“It’s an American problem,” Hill said. “We just have a front-row seat.”

Those who love free-flowing rivers see this problem as an opportunity. Their canyon is returning, and with it the rapids and awe-inspiring rock features. Others fear the price spikes that will come with replacing the dam’s hydropower with other sources, or the loss of a motorized playground that provided thousands of jobs for decades.

As the Southwest braces for a worsening water crisis, one of its major holding tanks faces a growing identity crisis. Nature will have the final word in determining what Powell becomes, further draining it if drought worsens or refilling it if a wet period ensues. If recent trends hold, federal water managers face tough decisions in the next few years about how hard to fight to retain a shrunken lake at Page, and at what cost to other resources and users up and down the river.

Drought weakens Lake Powell’s promise

Controversial from the start, 59-year-old Glen Canyon Dam arose as a compromise of sorts. Its construction sacrificed a secluded maze of desert river and side canyons after the U.S. rejected plans to flood other treasures, sparing places like Utah’s Dinosaur National Monument. After the dam buried Glen Canyon, environmental concerns ended a scheme for more dams in Arizona’s Grand Canyon, whose “grandeur,” “sublimity” and “great loneliness” President Theodore Roosevelt had famously cautioned could not be improved upon.

The government built Glen Canyon Dam in large part to ensure that exactly what is happening in 2022 would not happen. With Hoover Dam already impounding the nation’s largest reservoir in Lake Mead near Las Vegas, the river was ready to supply water to farms and cities in Arizona, Nevada, California and Mexico.

A second reservoir upstream at Lake Powell would almost double that capacity, theoretically ensuring that the headwaters states — Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico— could store enough water there near the Utah-Arizona line to top Lake Mead off when needed.

Instead, Lake Mead’s decline has already triggered mandatory shortages for the Central Arizona Project and the Southern Nevada Water Authority, with deeper cuts in store for next year. Arizona will give up about a fifth of its normal share of the river in 2023, deepening the hardship for farmers in the middle of the state and reducing cities’ ability to store water in their aquifers for later use.

California’s senior water rights have so far protected it from reductions. Arizona decades ago accepted junior rights as a condition of congressional approval for the CAP canal that delivers water to Phoenix and Tucson.

When the states and federal dam operators split up shares of the river on paper in the 20th century, they gave 7.5 million acre-feet of water to the three states below Lees Ferry, a spot downstream of present-day Glen Canyon Dam, and an equal share to four states that share the upper Colorado and its largest tributary, the Green River. That would add up to 15 million acre-feet, with a few million more dedicated to evaporation and Mexico. Yet in this century, the river’s natural flow has averaged far less than was spoken for, just 12.4 million acre-feet.

An acre-foot — the amount it takes to cover an acre to a 12-inch depth — is the government’s water accounting unit and contains about 326,000 gallons. Each acre-foot can support two or three households, though a large majority of the Colorado’s water goes to farms.

Now, mighty Lake Powell, big enough to fit 25 million acre-feet on its own, is just a quarter full. Dam managers made emergency releases from smaller upstream dams earlier this year to prop up the reservoir, and also held back 480,000 acre-feet that otherwise would have flowed to Lake Mead.

On paper, the government decided to treat those 480,000 acre-feet as if they were already in Lake Mead, to keep that reservoir’s official holdings from triggering even greater austerity on downstream users. Winter weather will determine whether Powell can afford to let that water flow downstream next year and still produce power.

For next year, an official with Reclamation’s Upper Colorado Basin office said, the agency will work with states on a plan to release more from upstream reservoirs and to determine what administrative steps are necessary to continue releasing only 7 million acre-feet a year from Powell, if necessary, an amount made possible by the cutbacks in Arizona, Nevada and Mexico.

In announcing next year’s shortage, Reclamation officials said the conservation efforts throughout the Colorado River basin must increase by 600,000 to 4.2 million acre-feet a year, depending on weather, to stabilize the reservoirs at current levels over the next four years. That worst-case figure, 4.2 million, represents more than a third of what the river’s flow has averaged during the long drought. It’s almost as much as California, the biggest user, takes from the river.

It’s unclear where such a large savings could be found, though the region’s Democratic senators won $4 billion in climate legislation passed this summer. It could help pay for efficiency upgrades and to compensate farmers who agree not to use their full share of the river.

‘I’m not the one draining this’

As the receding waters expose canyons, rock features and even whitewater rapids that long were buried under the reservoir, some who love the river for itself see nature reclaiming its rightful place.

“You can hear it,” Utahn Eric Balken said as he tromped through dense cattails and creekside willows during his first inspection of the reemerging Slick Rock Canyon, one of many remote watershedsnotched into Glen Canyon’s sandstone. “There’s lots of bugs buzzing around. I was stepping over frogs left and right.”

Discoveries like these thrill Balken, who directs the nonprofit Glen Canyon Institute. His organization has long advocated draining Lake Powell and storing its water downstream in the similarly depleted Lake Mead. Now, he figured, nature was doing his work for him. He and allies believe Lake Mead was always enough to serve the region’s needs, and that it makes little sense to divide the water now that it’s so low.

Motoring out of Bullfrog Marina in mid-August, he said he tries to keep a low profile when boating from canyon to canyon, given how attached house boaters and water skiers are to their impounded playground. Soon, though, it may not matter what anyone wants for Lake Powell.

“Guess what?” Balken said. “I’m not the one draining this.”

Slick Rock, south of Halls Crossing, now supported multiple beaver dams and ponds, but also held disappointments for Balken. Tumbleweeds choked the zone nearest the retreating reservoir, while a nonnative grass vine crisscrossed the creek bed and threatened to outcompete the native flowers and grasses seeking a foothold. There are remnants of a dam-altered floodplain that he hopes will fade as nature takes over.

A notch to the north, Lake Canyon, yielded unequivocal joy for Balken the next morning. He throttled his boat up the meandering sandstone canyon and past a slalom of ghostly gray cottonwoods that still jut from the flatwater that buried them in the 20th century. He drove a sand spike into the beach to secure the boat, marched through a wall of briars and over a logjam deposited by recent flash flood, then emerged into an open canyon with a flowing stream.

Soon, a rushing waterfall echoed from the canyon walls and pitched muddy water from its bedrock perch like a monsoon deluge draining from a flat-roofed adobe.

Walking up on resurrected features like this, or on rock grottos or natural bridges elsewhere around Lake Powell, feels a bit like discovering Atlantis, long rumored to exist under the sea but buried under the waves for ages. The upper reaches of Lake Canyon’s dam-flooded zone first saw daylight again some 20 years ago, but this particular waterfall remained inundated until more recently.

Even after the water retreated, Balken and colleagues three years ago walked across lakebed sediments that still entombed it. Flash floods apparently blew out those deposits to expose the falls, which in turn blew his mind when he first saw it and heard its power.

“I love to see a creek finding its original bed,” he said.

More consequential treats awaited as he ascended the canyon this time. Atop the falls, 15-foot willows sprang out of a cutbank and rang with birdsong, evidence that the native vegetation and rust-colored canyon wrens can quickly return here.

Around elevation 3,650 feet, a mark that first reemerged some 20 years ago, some willows reached to 40 feet. Then came the cottonwoods, towering kings of the desert oasis, first one seedling at a time, then in tall clusters at higher elevations, and finally in dense ribbons of forest. Underfoot, purple wildflowers sprouted. Cicadas droned.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, when Reclamation Commissioner Floyd Dominy pushed for and finished the dam, Balken said, the dam builder had argued there was nothing of value to preserve there. Indeed, into his old age early in this century, Dominy asserted that he had improved the environment.

“I believe that nature can be improved upon,” he told High Country News in 2000, when Powell was nearly full and only academics used the term “megadrought.”

“This is a miracle,” Balken said in Lake Canyon’s recovery zone. “Our values have clearly evolved. Clearly, there is something here.”

But one canyon’s gain may be another’s loss.

Jack Schmidt traveled to a park in Moab, Utah, on a June evening to explain the Colorado’s woes to a few dozen interested Utahns and Canyon Country visitors. Schmidt is a Utah State University watershed scientist who has spent his career studying the river, and he leads a band of regional researchers who publish science and policy white papers through the Center for Colorado River Studies. To his eyes, Glen Canyon’s reemergence is both locally beautiful and regionally troubling.

“Don’t kid yourself into thinking the only environmental issue is everything wonderful in Glen Canyon popping up again,” Schmidt said to the crowd assembled on folding lawn chairs for a weekly Science Moab discussion and movie viewing. (The post-apocalyptic sci-fi “Waterworld” was the flick that week.)

During the Obama administration he served as head of the Grand Canyon Research and Monitoring Center for 3 ½ years, and before that he proposed what would become a series of artificial floods from Glen Canyon Dam to push sand downstream and offset some of the dam’s profound damage to the Grand Canyon’s ecology.

Those floods are not officially on hold, according to the Bureau of Reclamation, though Lake Powell’s low water has complicated the prospects for releasing the water necessary to create them.

But Schmidt had another threat to Grand Canyon on his mind. Smallmouth bass were massing just upstream of Glen Canyon Dam, where the declining water levels brought the lake’s relatively warm surface close to the hydropower intakes. If enough bass or other nonnative, warm-water sportfish slipped through the turbines to start a downstream population, they could menace a recovering population of native humpback chubs.

If that happens, he said, it’s “game over” for a fish that has swum Grand Canyon for millennia.

Weeks after he spoke, federal biologists confirmed bass breeding in a riverside slough below the dam and sought to isolate and remove the young. Whether that incident foretells broader breeding success below Glen Canyon remains to be seen.

On that summer evening in the park, Schmidt urged his listeners to demand action if they care about saving the river environment. The United States must address two seemingly intractable problems, he noted: climate change and overuse.

The challenges of climate and overuse

Scientists have explained the long-term crisis that a warming Rocky Mountain region is imposing on the Southwest as a “hot drought.” As the region warms, even snowpacks that seem healthy while piled up in the mountains can result in a trickle into reservoirs after the atmosphere, stressed trees and dry soils soak up their share.

A 2017 study by scientists at the University of Arizona and Colorado State University found that warming exacerbated the current drought to reduce annual flows by about a fifth, and that unabated greenhouse gas emissions through this century could push losses to a third or more of the river’s normal flow.

The Bureau of Reclamation itself warned a decade ago that climate change would eat into the river. Its projections of a 9% reduction in flows by mid-century underestimated what has already happened to the river.

“The important point,” Schmidt told his audience that day in Moab, more than 300 miles from his home campus, “is I shouldn’t have driven down here from Logan in a gas-guzzling van and loaded the atmosphere with carbon, I guess.”

The second problem, overuse, is more immediate. In recent years, the dam-stored equivalent of the entire, shrunken river’s flow has gone to supply California, Arizona, Nevada and Mexico, including evaporation in Lake Mead. Although the less-populous upstream states of Wyoming, Utah, Colorado and New Mexico take much less, the combined effect is depletion of reservoirs that once held several years’ worth of flows.

Schmidt’s solution, he would later tell The Arizona Republic, is to reengineer Glen Canyon Dam to allow it to spill water into the river and through Grand Canyon even after it sinks lower than the existing hydropower intakes and bypass tunnels. That might require drilling new and lower tunnels through the sandstone beside the dam. At least, he said, the government must study that option, because without it the drought could push the reservoir into “dead pool,” when a river no longer flows from it until more snowmelt arrives to buoy the surface.

“We should know what it costs to bypass,” Schmidt said.

On that, Schmidt and Glen Canyon preservationists like Balken agree. The Glen Canyon Institute this summer joined the Utah Rivers Council and Great Basin Water Network in calling on the Bureau of Reclamation to study such a plan that would, effectively, allow managers to drain Powell while leaving the dam in place.

But Schmidt would not drain the lake. Instead, he said, lower bypass tunnels would allow the government to decide how much storage Lake Powell needs in order to consistently send water downstream based on Grand Canyon’s environmental needs. It would still hold back water, but in dry times Lake Mead would need to handle the bulk of the Southwest’s storage needs. Reengineering the dam could cost tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, depending on the design. The Bureau of Reclamation has directed $2 million toward a study of options.

“There’s no way in this country we’ll eliminate the potential storage at Powell,” Schmidt said. The question is how often it will be actual storage, and how often mostly potential.

Tough choices for recreation

The National Park Service has spent several million dollars extending concrete boat ramps at Stateline in the south of Lake Powell and Bullfrog in the north, to enable continued access for houseboats. But that work likely won’t be enough to support the park’s congressional mandate to manage for boat recreation, and so the agency is planning a bigger investment.

The Bullfrog Marina ramp can handle houseboats only until the reservoir’s surface sinks below elevation 3,529 feet, park officials said in August. By then the spring snowmelt runoff had helped the lake rebound past that point, precisely where it had hovered when Hill had drawn it on his whiteboard in March.

The Bureau of Reclamation’s current projections show Lake Powell likely dropping back below that mark in September but rising to it again by next June. Seeking a longer-term solution, the Park Service is applying $26 million in federal disaster funding it received this year toward building a new ramp at Stanton Creek, a nearby but deeper part of the lake that could reach elevation 3,450 feet. That would enable boating well after the reservoir drops below the point of generating electricity.

The uncertainty is forcing boaters to make hard choices. Tom Parker, a semi-retired contractor from Erda, Utah, wasn’t sure whether to haul his houseboat out from its mooring at Bullfrog as the season winds down. He wanted to get it on dry land to scrape off the quagga mussels that crust over the hull, the engine and water intakes. But with the reservoir continuing to fall, he wasn’t sure he could risk it.

“If you get it out, you might not get it back in. That’s the problem,” he said while lining up on the ramp on a mid-August morning.

Parker was launching personal watercraft for his children and grandchildren to zoom around on during a stay on the houseboat. That’s something he’s done routinely over the years, as someone from his extended family visits the boat at least every other week in summer. Some even work remotely from it now that there’s a satellite internet link.

“It’s the best vacation we have,” he said.

The Park Service reported 3.1 million visitors to Glen Canyon last year, and they supported 3,840 jobs in gateway communities like Page by spending $332 million.

‘You can’t improve on nature’

Balken, the activist who longs for the reservoir’s demise and the river’s return, acknowledges that lots of people love lake recreation. Before them, though, there were those who loved the river and loathed what became of it after the dam. They include people he has known, like the late singer and renowned river guide Katie Lee, who didn’t live to see Glen Canyon’s return, and Ken Sleight, also a pre-dam guide and one who still yearns for the death of “Lake Foul.” Balken said he’s motivated partly by “the pain of their loss.”

One of their losses was Cathedral in the Desert, a shady sandstone grotto in a side canyon that admits a beam of sunshine to backlight a ribbon of water falling through a narrow slot. It was a place Sleight discovered while guiding tourists out of Escalante, Utah, on horseback before Lake Powell flooded it. Today, it’s back from the depths.

When Balken approached its sandy base in bare feet this summer, he found a row of rocks that someone had placed as a dam across the stream at its base, perhaps to raise a pool for bathing beneath the falls. He promptly chucked the rocks aside.

“You can’t improve on nature,” he said.

At home outside of Moab, Sleight looked at freshly shot digital photos of his beloved Cathedral in the Desert, and at new images of other side canyons. Their rebirth pleased him, but had taken too long.

“I don’t think I’ll be doing any more river running,” he said. “I wish I could.”

Sleight spoke softly and haltingly while sunken into his sofa, worn down from days of waging his own struggle with the fickle climate. A wildfire last year denuded the hills above his home, and recent monsoon rains had rushed over the bare ground and washed out small bridges on his property. He and wife, Jane, had been busy with repairs.

In younger days, the guide had befriended author Edward Abbey partly out of a shared disdain for the dam, and he had inspired a character, Seldom Seen Smith, in Abbey’s signature novel, “The Monkey Wrench Gang.” He still invokes his late friend’s prayer “for a precision earthquake to take down the dam,” but says he doubts it will now take an act of God to drain the reservoir.

“I’m 93 now and I don’t have too much time to live,” he said, “but I’m sure hoping I can live long enough to see it go.”

If the Colorado does flow freely through Glen Canyon again, he fears, there will be a new threat: people. Even before the dam, he remembered, the place had become crowded for his taste. A renewed Glen Canyon will require careful management, he believes. “It’s going to attract thousands, because it’s so beautiful.”

Amid new beauty, dangers lurk

From an airplane over Lake Powell’s upper reaches, the folds and crevasses of mud resemble a dirty glacier plowing through the Colorado Plateau.

As the reservoir retreats from the floodplain’s edge, where for decades the river dropped sediment it had eroded from points upstream, the accumulation slumps raggedly away from sandstone walls as a fault line would in an earthquake.

This is no flightseeing tour of geologic time, exhibiting Earth’s grindingly slow mechanics as they carve Canyon Country’s latest wonder. It is instead a real-time window on the fast-moving consequences of a changing, drying regional climate and the Southwest’s slow response to it as Lake Powell drains toward oblivion.

River rafters paddling or motoring down from Moab years ago were forced to abandon the Hite takeout ramp on the narrow upper lake’s east side, in favor of an intimidating gravel incline called North Wash on the west side. The makeshift ramp has steepened as the bank at its bottom continues to slough, making for a difficult retrieval of the big, motor-equipped rafts that tour company guides pilot down from Moab daily in summer.

After customers step out and walk toward a waiting bus, a pickup with a trailer backs gingerly down the top of the embankment and sets its brake. Guides from multiple boats then push and pull the rafts uphill on inflatable rollers. The combination of massive loads on the hill and deep muddy waters at the bottom requires vigilance.

“It’s scary,” Hannah Wood, a seasonal Moab-based guide from northern Utah’s Salt Lake valley, said when she arrived at North Wash after a June trip. “Every time we come here I’m worried someone will die.”

Wood said a colleague had fallen at the ever-changing takeout’s edge, and had cut himself on the raft’s motor. While the rapids upstream in Cataract Canyon are supposed to be the trip’s big thrill, she said, takeout at this site is “the most dangerous part of our job.”

The only other place to take out is at Bullfrog Marina, a two-day motor across flatwater. But even that has become problematic for operators of larger rafts, as the shifting and shallow mud beneath the delta that’s emerging downstream of North Wash can trap the heavy rigs.

The river also appears to be building a waterfall over a sediment deposit upstream of the North Wash takeout, threatening further complications.

The same thing happened hundreds of miles downstream when Lake Mead drained away from the lower Grand Canyon. There, a waterfall made Pearce Ferry the final takeout chance for Grand Canyon river trips.

Already, North Wash is “probably the worst boat ramp in North America,” Moab river runner and pilot Chris Benson said while looking down from a rented four-seat Cessna Skyhawk that’s usually used to give rafting patrons a look at Canyonlands National Park on the way back to their cars in Moab.

Benson’s friend, river guide Pete Lefebvre, pointed to a muddy riffle upstream of the ramp, near where the Dirty Devil River meets the Colorado, fresh evidence of a fast-changing landscape. “That wasn’t there two days ago,” he said.

Benson and Lefebvre are amateur “investigators” with a small nonprofit group of river enthusiasts called Returning Rapids. They photograph and share changes in the river and lake environment as the water recedes. Their work can help other recreationists navigate new hazards, but increasingly they also want government officials to take notice. As the reservoir’s northern edge creeps downstream, they say, the river is pushing its mud delta farther south.

This mud is what the group considers the “tailings” from the region’s “mining” of the Colorado River: The West used up the water and left a mess more than a hundred feet deep. They call these deposits the “Dominy Formation,” in honor of the late dam builder.

Farther downlake, the San Juan River, a major tributary that joins the reservoir, has pushed its delta closer to Lake Powell’s main channel. When that happens, possibly in a few years, they fear the band of mud could at least temporarily cut Lake Powell in two, creating a new set of hazards.

Who will mind the mud? How will it affect recreation, the environment and safety? To date, there’s no plan.

“Are we making a conscious decision?” Lefebvre said. “Or are we just saying, ‘Oh, that’s Lake Powell. That’s just what happens.’”

Worried as they are about the mud, Returning Rapids members are unabashedly joyful about what else the reservoir’s decline is giving them. It’s in their name: the whitewater rapids that are rising again from lower Cataract Canyon, the river stretch that is no longer inundated.

Eleven rapids have returned, clearly visible from the air and adding about 50% more fun to the 22 that the float trip previously offered. Lefebvre points them out from above, each the result of a side canyon whose drainage has poured boulders into the Colorado over the ages. Several of them have emerged alongside sandy camping beaches of the sort that river runners covet.

“Good for us!” Lefebvre said.

At North Wash, where Wood was helping offload rafting clients and trailer the rafts in June, one client said he had a blast on his multiday river trip, but worried about what Lake Powell’s plunging waterline portends.

“In 20 years the Colorado River won’t be here,” said Jeff Dudek, a tourist from Prairieville, Louisiana, “unless something drastic happens.”

Will hydropower survive the crisis?

More than 4 million Americans who buy Glen Canyon Dam’s power also stand to lose as the water recedes. Consumer-owned utilities from Arizona to Wyoming, including Native American entities like the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, will need to add new and likely costlier sources to their mix.

Supplemental sources could include solar, pumped-storage hydro projects or even small, modular nuclear plants, said Leslie James, who directs the Colorado River Energy Distributors Association. If Glen Canyon loses all of its power-generating capacity, it would shut off the primary revenue source that pays for the dam’s operations and maintenance. The dam accounts for $119 million of the $150 million that electric generation pumps into a basin fund that also aids environmental initiatives on the river.

Looking at the government’s current projections for flows and reservoir levels, she fears Glen Canyon water will dip below the minimum level for power production by 2024.

Before then, James hopes, a bill proposed by Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., could help limit the pain. Kelly’s bill would keep the government from collecting standard operations and maintenance or dam financing fees from hydropower customers when the dam isn’t actually churning out electricity because of drought.

Improved forecasting technology could help the Bureau of Reclamation fine-tune releases from upstream reservoirs such as Navajo or Flaming Gorge to maximize their effect. Ultimately, though, the river’s hydropower users are at nature’s mercy.

“It needs to rain and snow,” James said.

Learning to live with less

At the Navajo community of Lechee, outside of Page, coping with drought is a way of life. The houses, many of them mobile homes, have brown yards. Rural residents beyond the village have cut back on sheep and cow herds, partly to offset the cost of hauling water and partly because there’s little grass for the livestock to eat.

And yet, like Page, Lechee exists as a population center because of Lake Powell and access to its water.

“My parents remember when it was just a little bitty stream, before the dam came,” said JoAnne Yazzie-Pioche, who heads local government as the Lechee chapter president. Navajos made do with groundwater pumped by windmills, and did not build their homes next to each other.

Then Page tapped the dam, and Lechee got access to water piped from the same intake. With that, some congregated around the village water tower, while others remained in rural homes but trucked water from a filing station in town. They brought water to maintain livestock, but are now culling herds because of both the expense of hauling and the drought-stricken forage.

Watching Lake Powell’s decline has been painful for Yazzie-Pioche, for multiple reasons.

For one, her dad was a laborer who helped build Glen Canyon Dam during her childhood. She frequently boated and camped on the lake for recreation while raising her own children, back when the monolith Lone Rock on the lake’s south end was surrounded by water.

“We love Lake Powell,” she said, though her children have grown and moved to metro Phoenix, and the lower water has reduced the draw for her personally. “It’s sad to see. And not a whole lot of beaches. But still, people do come.”

Her community, like neighboring Page, is hoping for a new water source that draws from deeper than the dam’s hydropower intakes. The Navajo Nation has begun work on a pipeline from the pump upstream of the dam that supplied cooling water to the now demolished coal-fired Navajo Generating Station.

Even before it comes online, the plunging water line is raising questions about this new source’s viability.

“We’re just like, ‘Great. We finally have access to Lake Powell on this side, on the (Navajo) Nation’s side, but the water’s going down,” Yazzie-Pioche said.

The Southwest must learn to live with less, she said, from the lawns of Phoenix to the farms of Yuma. Whatever happens along the Colorado, though, there will still be windmills around Lechee.

“We’re always going to be here,” she said. “We were here prior. Even when we had no water, people still lived here.”

Page was not there before the big water. It was founded in the 1950s to house the workers who built Glen Canyon Dam. They came to improve on nature.

“The federal government built Page,” said Hill, the city’s utility director. ‘Yea verily,’ in 1957 they said, ‘There shall be Page.’”

It was a proclamation with echoes across the Colorado River’s 1,450-mile length, not least along the federally backed projects importing water to Phoenix and Los Angeles.

What the government created, Hill said, the government should fix. Page needs a new and deeper intake beyond the quick fix that the Bureau of Reclamation is planning within the dam. A new intake outside of the dam would protect the city’s supply of drinking water even if drought pushes the lake to “dead pool,” lower than the dam’s bypass tunnels. But it will cost $40 million, he said. The city is angling for federal funds to build it.

Whatever identity Lake Powell ultimately assumes, the costs will ripple far beyond its waters.

Brandon Loomis covers environmental and climate issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com.